When Disco Fever Raged

Pulsating music, strobe lights and postage-stamp dance floors packed with shimmying bodies. Tan Chui Hua gives you the lowdown on the history of the disco scene in Singapore.

The 1977 hit film Saturday Night Fever epitomised the global discotheque scene in the 1970s and early 80s. Starring John Travolta in his breakout role and Karen Lynn Gorney, and featuring music by the Bee Gees, the film played in Singapore cinemas for weeks to sell-out crowds. Needless to say, discos here saw an immediate spike in patrons, with many replicating the slick moves of Tony Manero (the character played by Travolta) on the dance floor.

The 1977 hit film Saturday Night Fever epitomised the global discotheque scene in the 1970s and early 80s. Starring John Travolta in his breakout role and Karen Lynn Gorney, and featuring music by the Bee Gees, the film played in Singapore cinemas for weeks to sell-out crowds. Needless to say, discos here saw an immediate spike in patrons, with many replicating the slick moves of Tony Manero (the character played by Travolta) on the dance floor.caught slow-motion

by insidious search-light eyes

as phantoms writhing

drowning in a wet haze

of a multi-coloured dream

gone psychically mad

a nightmare born out of wailing voices

washed away unheard

for some prehistoric rites”

– Chen Nan Fong, 19711

When Gino’s A-Go-Go, Singapore’s first discotheque – or disco for short – opened along Tanglin Road in 1966, it seemed like a laughable idea to many locals. Accustomed to live bands and tea dances, they thought grooving to the canned music of British teenage pop sensation Bee Gees at Gino’s was a strange thing. In fact, the press described the upstart’s debut as having an “atmosphere of closed camaraderie that you can only find on a postage-stamp size dance-floor packed too tightly to waltz in”.2

But Gino’s, bankrolled by Herbie Lim, grandson of rubber king Lim Nee Soon and riding the discotheque fever sweeping across fashionable cities of the world, soon began seeing long snaking queues of mainly young people every night.

Ronald Goh, whose family business Electronics and Engineering installed the discotheque’s state-of-the-art sound system, recalled: “The DJ was not much of a DJ, except that he played… you know there was two turntables, and he alternate[d] sounds from one vinyl to another.” Goh explained: “The DJs were university students, they came in the evening and ran the disco… this was just the beginning, where they actually play vinyl, or records, over a sound system with a dance floor and started this disco fad.”3

Despite Gino’s success, disc-jockeys (or DJs as the word later became abbreviated) – whose job was to spin gramophone records or discs on a turntable – would remain an anomaly in Singapore for a while longer. It was, after all, the heyday of live bands in Singapore and they were not going to be upstaged so easily.

Discos, Discos Everywhere

There was a lull until 1969, when two disco clubs opened – Fireplace on Coronation Road and The Cosmic Club on Jervois Road. As the revelry from Fireplace continued until the wee hours each night, a series of complaints by irate neighbours led the police to shut it down.4 The Cosmic Club was short-lived too: the police declared it an unlawful club on the grounds that the club was “prejudicial to public peace and good order” and that “such a club would attract young Singaporeans in their impressionable years… to demoralise and create a sense of false values”.5

The warning came too late. When the hotel development boom of the late 1960s and early 70s descended upon Singapore, hoteliers caught on to the fact that having an in-house discotheque would be a sure-fire way to attract young Singaporeans looking for novel ways to entertain themselves. A slew of new discos opened in quick succession in various hotels in town: Ming Court’s Barbarella (1969), Equatorial’s Club Crescendo (1969), Cuscaden’s The Eye (1970), Hilton’s Spot Spot (1970), Shangri-La’s Lost Horizon (1971), Mandarin’s Boiler Room (1971) and several others.

With the revival of discotheques in the late 1970s, the former Lost Horizon at Shangri-La Hotel was revamped to become Xanadu. Opened in 1981, the million-dollar discotheque boasted complex laser effects, a high-tech sound system and plush interior décor. Courtesy of Shangri-La Hotel, Singapore.

With the revival of discotheques in the late 1970s, the former Lost Horizon at Shangri-La Hotel was revamped to become Xanadu. Opened in 1981, the million-dollar discotheque boasted complex laser effects, a high-tech sound system and plush interior décor. Courtesy of Shangri-La Hotel, Singapore.Existing nightclubs and lounges, such as Pink Pussycat in Prince’s Hotel Garni, began rebranding themselves as discotheques with resident bands to draw the crowds. Psychedelic lighting and loud décor became must-haves. The hype rose to fever pitch when Pierre Trudeau, then Canada’s prime minister, was seen “getting down” on the dance floor with a local former model at Spot Spot during his visit to Singapore in January 1971 to attend the meeting of the Commonwealth Heads of Government.6 The press had a field day with the story.

The Pink Pussycat at Prince’s Hotel Garni on Orchard Road began rebranding itself as a discotheque with resident bands to draw the crowds. Featured here is local band The Hi Jacks in a photo taken on 30 May 1973. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reprinted with permission.

The Pink Pussycat at Prince’s Hotel Garni on Orchard Road began rebranding itself as a discotheque with resident bands to draw the crowds. Featured here is local band The Hi Jacks in a photo taken on 30 May 1973. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reprinted with permission.The flurry of discos opening inevitably led purists to question – what exactly is a discotheque? The word “disco” is derived from the French word disque, which means discs or gramophone records, so if one goes to a library or bibliothéque in France to read books, then by extension a discothéque is where one goes to listen to records.

“There should be no live band in a discotheque,” Kim Khor, then manager of Soundbox at Hotel Miramar, sniffed. “Our locals don’t appreciate discotheques. They prefer live bands, something which is difficult to understand.”7 Soundbox, which opened in 1971, was touted as Singapore’s second discotheque in the truest sense of the word.

For disco fans in Singapore, however, what really mattered was a good party: loud music, light effects and a small dance floor packed to the brim.8 Disc jockeys, it seemed, were not the main attraction. A 1971 tabloid noted:

“When is a disco not a discotheque? When there is a live band but no discs. Which means that all the swinging joints in town are not discos in the true sense of the word. This controversy over the definition of this particular brand of night clubs has been aired. But who cares? A squeezy dancing floor with an electronic band blasting away the ears and walls has got the discotheque label slapped on it.”9

War of the Dance Floors

As more discotheques opened, the share of the disco-goer pie began shrinking in proportion. By 1970, business owners were complaining that the industry was no longer a “paying proposition”.10 The long queues outside star establishments, however, kept the hopes of new entrants into the disco scene high.

Staying on top of the game called for more innovation and offerings. The owners of Barbarella at Ming Court Hotel sank more than $300,000 to set up the three-level establishment, with its iconic space-age design inspired by its Jane Fonda movie namesake – somehow looking at odds with Ming Court’s staid Oriental-inspired décor. Every month, $30,000 went towards the cost of hiring live bands, and another $4,000 for renting psychedelic slides for 16 projectors.11

Barbarella discotheque advertising performances by its foreign band, The Pitiful Souls. Image reproduced from The Straits Times, 3 January 1970, p. 20.

Barbarella discotheque advertising performances by its foreign band, The Pitiful Souls. Image reproduced from The Straits Times, 3 January 1970, p. 20.Not to be outdone, Spot Spot plastered its walls with thousands of sparkly red sequins and imported an antique bartop from Malacca for serving cocktails and alcoholic drinks. Lost Horizon took discotheque fantasy up a notch with a seafaring theme, complete with custom-built gondolas, Chinese junks, Portuguese fishing boats and a French man-of-war. Winsome female greeters dressed in nautical gear, while slide projections of Venetian scenes and themed drinks ensured an over-the-top experience.12

Discotheques began scouting for better, newer and more famous bands, many of them from overseas, to the point it was noted that “very few local bands can make it to the nightclub scene these days” as “there are so many bands around – some very good, some above average, others average and of course some below average”.13 Discotheques also began holding lucky draws, costume parties and games to bring in the crowds. The Boiler Room, for example, started weekly disc jockey contests and tied up with record companies to hold launch parties for new album releases.

But the proverbial pot of gold, for most disco operators, turned out to be mere wishful thinking. Disco clubs became trapped in a web of spiralling costs. The disco set was, after all, made up of Singapore’s young, with plenty of aspiration but limited fiscal power. While popular bands cost more to hire, cover charges had to be priced affordably for young people. Gino’s, which had rebranded itself as Aquarius, was one of the few exceptions because it did not hire bands.14

Disco-on-the-Move

In the late 1960s, when it became clear that hiring live bands was unsustainable in the long run, Larry Lai, a Rediffusion DJ,15 began toying with the idea of the mobile disco, calling his outfit Moby Dick.16

“For an initial fee of $250, Moby Dick performs non-stop for four hours and gives you that ‘disco’ setting in your own parlour, club, or simply ‘where-you-want-it’ – complete with ultra-violet and strobe lights and a disc-jockey who will act as MC for your party, plus these two a-go-go girls.”17

Radio and Rediffusion stalwart Larry Lai, 1975. Together with Mike Ellery, Rediffusion’s manager for English programmes, Lai started a mobile disco called Moby Dick in 1970. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reprinted with permission.

Radio and Rediffusion stalwart Larry Lai, 1975. Together with Mike Ellery, Rediffusion’s manager for English programmes, Lai started a mobile disco called Moby Dick in 1970. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reprinted with permission.His idea, however, was met with scepticism: the general response was “What! Pay you to dance to records? You are crazy. I can do that free at home.”18 Ignoring the naysayers, Lai teamed up with Mike Ellery, Rediffusion’s manager for English programmes, and registered Moby Dick as a partnership in 1970.

Having a great business idea was one thing; making it work was another. Technical challenges had to be overcome – from nailing the right sound and volume to the right lights and effects. Hagemeyer, the distributor for National products in Singapore, sponsored the company’s speakers, amplifier and turntables. Lai’s engineer colleagues at Rediffusion reconfigured the equipment into a mobile disc jockey station.19 Next came the lighting effects. Lai explained:

“The technology was there but we needed more than just flickering colour lights. We needed something to ‘wash’ walls and stuff like that. So the simplest thing that we could do was to buy a slide projector and then do our own colourful psychedelic slides… and then Mike had the brainwave of getting an all-beat-up speaker with no sound, but if you put in a signal, a sound input, and you turn up the volume a little bit, the speaker cone would vibrate. So we stuck little pieces of broken mirror… then we paint[ed] it… the mirrors with little bit of DayGlo paint, then we shone a spotlight on to the speaker cone[s] which then reflected little flickering light[s].”20

Moby Dick rolled into action. Pamphlets were sent to prospective clients, such as clubs, hotels and military camps. Lai and Ellery found two Ford Falcons – large cars with bench seats – and piled the equipment in the back while ferrying a sexy go-go girl each in the front. Friends in the press wrote up articles on the “new fad” to generate public interest. Then calls started coming in. Lai said:

“The only people who knew what mobile discos were all about were the British military, the Australians, all the Caucasians from either Australia or Europe or America.

“Only they would give us the business. So we played [at] the British military camps, the Kiwis in Sembawang. Then we played at the American Club, the Tanglin Club, Singapore Cricket Club… the memberships were all heavily foreign.”21

To create a disco night mood, Ellery and Lai imported psychedelic posters of icons such as The Beatles and Jimi Hendrix painted in luminous colours and ran an ultraviolet light over them: the effect was surreal. The song list was peppered with bubblegum favourites to get feet tapping. When the go-go girls in bikinis got up to dance on tabletops, DayGlo paints were provided and male patrons were invited to paint the girls’ bodies. As Ellery described it: “Getting pretty girls involved, greater traction… well it’s a show! It makes a better show, more fun.”22

Bikini-clad a-go-go girls and DayGlo body painting were part of the package offered by Moby Dick, Singapore’s first mobile discotheque. Image reproduced from The Straits Times, 20 September 1970, p. 6.

Bikini-clad a-go-go girls and DayGlo body painting were part of the package offered by Moby Dick, Singapore’s first mobile discotheque. Image reproduced from The Straits Times, 20 September 1970, p. 6.Word got around. The hotels finally caved in, scaled back on live bands and engaged DJs instead. Moby Dick started landing contracts with hotels, clubs and restaurants. Ellery and Lai found themselves having to hire more DJs and roadies to run the shows, and this was how DJs such as Brian Richmond, Victor Khoo and Bernard Solosa – who later became household names in the 1970s and 80s – first cut their teeth. Mobile disco businesses opened one after another, and Brian Richmond launched his own outfit a few years later.23 The age of true discotheques had finally kicked off.

In retrospect, the shift was unsurprising as Ellery noted:

“Mobile disco is consistent and affordable. And we always got the latest pop tunes straight off the charts. We fly them in. … Sometimes I believe the hotel would have its own system already in, and we would probably add on a bit to it, the speaker systems and all that.”24

In an article that Brian Richmond wrote on the golden age of disco, he said:

“It is hard to describe the magic of those days. DJs were entertainers. For instance, I used to play the congas, sometimes we would rap between songs; the onus was on us to get the crowd warmed up, and their feet and bodies moving. We would sing the chorus, play the favourite songs of regulars, and greet people we recognised. These were tricks of the trade – to make someone feel good, welcoming them by name; also to know when to keep mum because someone was there and not wanting to be seen! We would do the fast music, then at some point, dim the lights and do the lovey-dovey music for people to smooch to… then we would bring up the tempo again. The DJ was king, and he dictated the scene.”25

Brian Richmond in his element, 1976. He started out as a mobile disco DJ and became a household name in the 1970s and 80s. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reprinted with permission.

Brian Richmond in his element, 1976. He started out as a mobile disco DJ and became a household name in the 1970s and 80s. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reprinted with permission.The Clamp Down

The permissive 1960s gave way to the puritanical 70s when the government decided it was time to stem the tide of – or at least the perception of – rising immorality in Singapore. Discotheques, with their predominantly young crowds, unsavoury reputation and association with drugs, brawls and “permissive behaviour”, became prime targets.26

In 1971, a 100-percent increase in entertainment tax was imposed on all venues with live bands, and nightclubs in the central district were forbidden from remaining open after 1 am on weekdays, except on the eve of public holidays.27 In 1972, the Ministry of Home Affairs ordered a three-night surveillance on nightspots on Orchard Road. The ministry said that entertainment places doubled as drug distribution centres, in particular for Mandrax or MX pills (a type of hypnotic drug) and ganja (cannabis), and concluded that “these nightspots and youthful customers have common characteristics: psychedelic lights, abstract art, loud ‘soul’ music, long hair (or wigs), coloured T-shirts, denim jackets with badges and signs, bell-bottoms, loose blouses and jockey-caps”.28

In July 1973, then Minister for Home Affairs Chua Sian Chin delivered a stern warning to nightlife establishments, singling out discotheques in particular. He said:

“I am informed that our discotheques are places which are predominantly patronised by local youths, especially long-haired teenagers, who go there to revel in star-wandering rock and soul-moving music in a hallucinatory atmosphere so familiar with the drug and hippie cult.”29

Following his warning, six discotheques were closed down in November that year, including Mandarin’s Boiler Room and Ming Court’s Barbarella. Twelve highly popular discotheques, such as Lost Horizon and The Eye, lost their liquor licences. Hotel discotheques providing public entertainment were no longer allowed to serve alcohol.30

For nightspots that remained opened, a long list of strict conditions was imposed for their continued operations. These included the prohibition of alcohol, psychedelic lighting, private cubicles and lewd images. Persons under 18, long-haired men and patrons not sporting a tie or wearing a national dress were denied admission. In addition, operating hours had to cease at midnight, with an hour’s extension on Saturdays and public holidays; in the event of breaches, the payment of a substantial cash deposit would be totally or partially forfeited.31

Mervyn Nonis, a musician with popular local band The X-periment, recalled those grim days. He said: “… all the clubs were just… All closed, you know, so there was no entertainment, you know. At all… You could just imagine the scene. All the bands were jobless….”32 And then, in a final death knell to the disco scene in Singapore, dancing was banned in most discotheques by end 1973.33

These curbs hit the discotheques hard. The fierce competition among nightspots in the early 1970s had already taken a toll. Some, such as The Eye, tried to adapt by hiring extra guards to turn away undesirable patrons and raising cover charges and the prices of drinks. Some, such as Spot Spot, had already closed down in 1972 due to market stresses and increasing government surveillance. The others converted into cocktail lounges and bars that were less stringently monitored by the authorities.34

Nonis remembered that bands and DJs took turns to perform on the dance floor after the dance ban:

“… the clubs were allowed to open. But no dancing was allowed… You just watch. And we used to alternate with Brian Richmond… So Brian Richmond, the equipment, was on the dance floor… Just music and then… so when we came on, it was like a show band sort of thing… What we felt was the public was not getting enough. Like, when they used to go to the clubs, that means they couldn’t let themselves… go. Or let the [their] hair down… So… I think it was a bit boring… Because how long could you just listen and do nothing, you know what I mean?”35

It was only in 1975 that the government began rolling back some of the restrictions. Male patrons without ties were no longer barred, business hours were extended and liquor licences were reissued. Strobe lights and private cubicles, however, were still a no-no and projectors were not allowed. The damage, however, had been done. The disco scene was a shadow of its former self. In 1977, the grand dame of discotheques, Barbarella, closed for good.36

Can’t Beat ’Em, Then Join ’Em

When the American musical drama Saturday Night Fever, with John Travolta in his breakout Hollywood role and songs by the Bee Gees hit Singapore’s cinema screens in 1978, all things disco – fashion, music and slick dance moves – resurrected with a vengeance. New discotheques opened, and demand for disco dance classes grew. The national hunt for representatives in Singapore to take part in EMI’s annual World Disco Championship in London was launched in 1979.37

Realising that there was no trumping the popularity of Hollywood, the government took a different tack. In 1978, community centres began organising disco nights for young people, to the point that disco dancing, “once associated with shady discotheques”, was fast becoming the rage in Singapore’s community centres. The main difference was that only sugar-spiked soft drinks were served.38

“Respectable” folks began jumping on the bandwagon. The Singapore Armed Forces started disco dance classes. Charities, festivals and other events held disco nights to attract young people. Even the Young Men’s Christian Association got into the act, launching its own version of a “clean” discotheque that did not serve liquor in 1975, and organising Singapore’s first disco queen competition in 1978, complete with fog and bubble-making machines as competitors danced in cages.39

The first disco dance organised by Bedok Zone 4 Residents’ Committee at the Bedok Central Area Office in 1986. The event was officiated by then Minister for Home Affairs S. Jayakumar. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The first disco dance organised by Bedok Zone 4 Residents’ Committee at the Bedok Central Area Office in 1986. The event was officiated by then Minister for Home Affairs S. Jayakumar. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.In 1979, the New Nation made the following observation:

“Saturday night has never been so feverish in Singapore. The disco industry sustains a baker’s dozen of discotheques in top hotels – with prices to match. There… the energetic generation gets its exercise on postage-stamp-sized dance floors. Lower down the socio-disconomic ladder, thousands flock to the Leisuredrome to disco rock the weekend away at Kallang. Even community centres have seen the strobe light.”40

And as a final feather in the cap for the industry, the police embraced disco. In December 1985, the first police disco for teenagers was held during the school holidays, and the response was “quite positive”. In February the following year, the police force launched a mass disco Lunar New Year party for 4,000 young people at World Trade Centre, featuring Dick Lee and his All Star Variety Band, a fashion show, and appearances by local artiste Jacintha Abisheganaden and bands such as Tokyo Square and Culture Shock.41

It had taken over a decade since Gino’s, but discos in Singapore had finally made it to the mainstream.

JUMPING ON THE BAND-WAGON

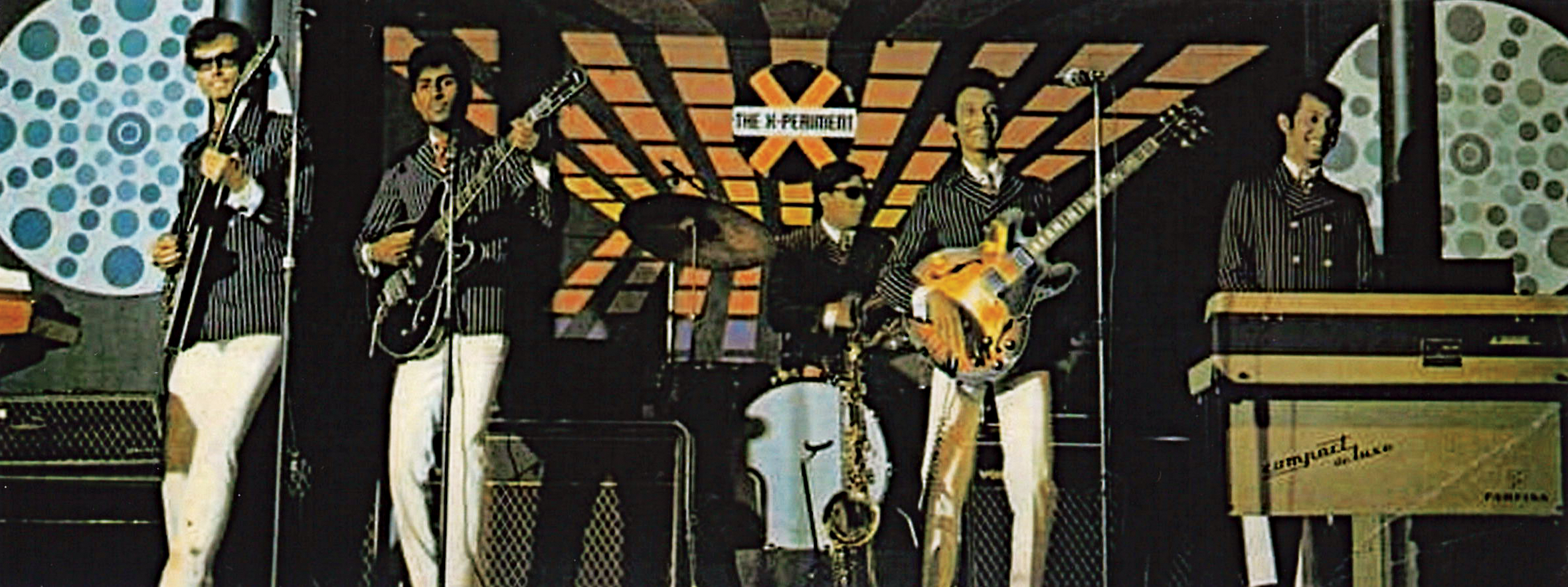

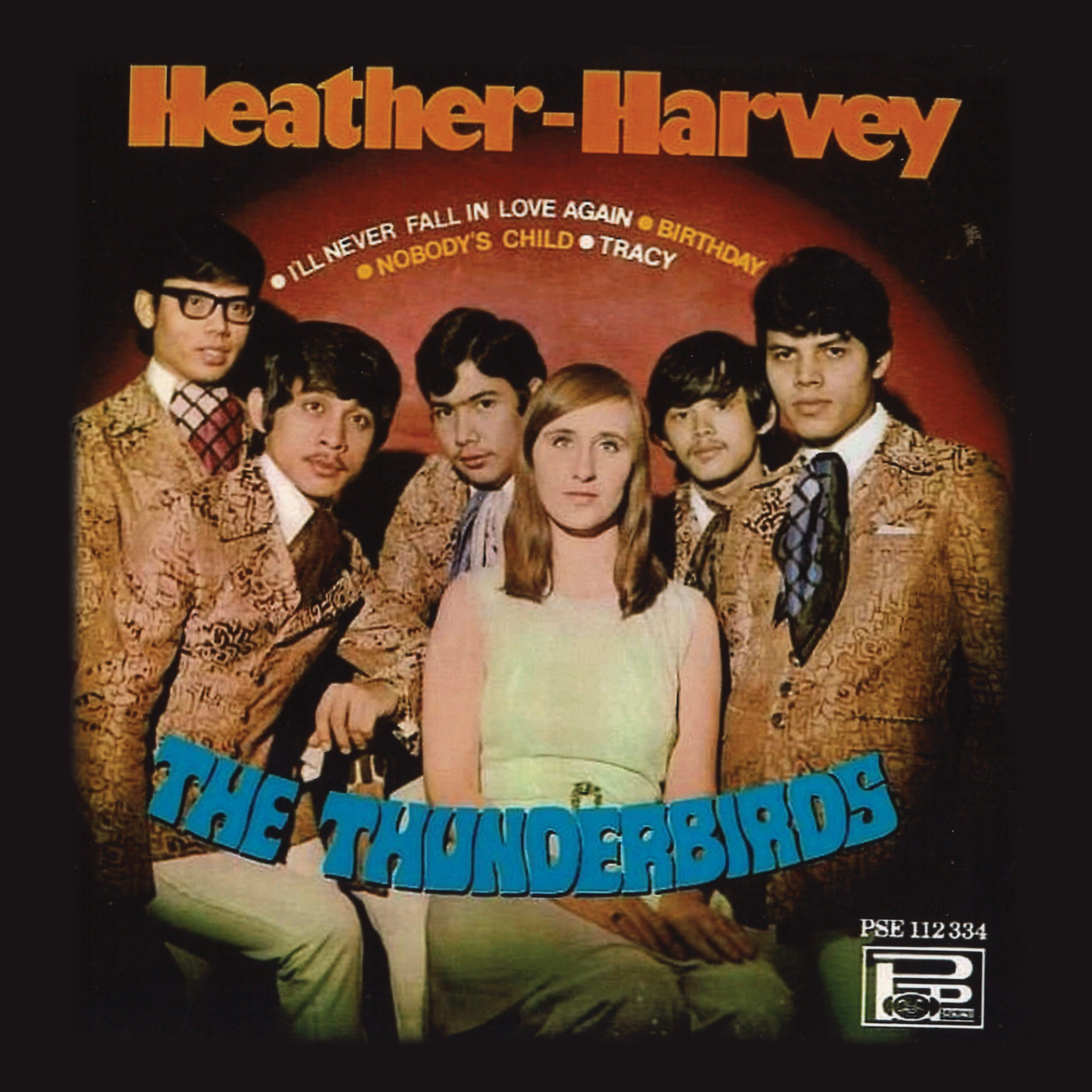

In the early years of discotheques, bands were a big part of the attraction. Getting “better and better bands” was a strategy to hold the attention of fickle crowds.42 Popular local bands, such as The X-periment, Flybaits, The Hi Jacks, Blackjacks, the X’Quisites, and Heather and the Thunderbirds, landed lucrative contracts.43

The X-periment, which was formed in 1967, performing at the Baron Night Club on Upper Serangoon Road where it held a lengthy residency. Courtesy of Joseph C. Pereira.

The X-periment, which was formed in 1967, performing at the Baron Night Club on Upper Serangoon Road where it held a lengthy residency. Courtesy of Joseph C. Pereira.

For instance, in 1973, Heather and the Thunderbirds signed an 18-month contract worth $144,000 with The Pub in Marco Polo Hotel.44 Many local bands, after establishing themselves in Singapore, were offered attractive contracts to perform overseas in cities such as Hong Kong and Bangkok.45

By 1970, the demand for good bands was so intense that many discotheques turned to foreign bands. Performers were brought in from the Philippines, Indonesia, Australia, the United States and even Europe. While local bands cost a minimum of $3,000 to $5,000 a month, imported bands cost at least three times as much. Filipino and Indonesian bands were said to be cheaper than non-Asian bands, which commanded around $10,000 a month, with one nightspot reportedly paying $18,000 a month for its foreign resident band.46

Such heady days were soon to pass, however, with the introduction of mobile discos as well as the government crackdown on nightspots.

The Thunderbirds was formed in 1962 and evolved over time to include lead vocalist Heather Batchen. (an English girl living in Singapore who adopted Harvey as her second name after she married fellow band member Harvey Fitzgerald). Featured here is their album released by Philips subsidiary Pop Sound in 1970. Courtesy of Joseph C. Pereira.

The Thunderbirds was formed in 1962 and evolved over time to include lead vocalist Heather Batchen. (an English girl living in Singapore who adopted Harvey as her second name after she married fellow band member Harvey Fitzgerald). Featured here is their album released by Philips subsidiary Pop Sound in 1970. Courtesy of Joseph C. Pereira.

NEW-AGE DISCOS

Discotheques in Singapore continued to adapt to changing times in their bid to attract partygoers. Starting with the Top Ten club in Orchard Towers in 1985, discotheques did away with their postage-stamp-sized dancefloors and opted for mega spaces instead. Techno pop and remixed pop and rock replaced Bee Gees and Boney M, and live bands and singers were reintroduced.

Outside the English-language circuit, the 1990s also saw a series of Cantopop discotheques and clubs popping up as Hong Kong’s music industry swept the region. These new establishments, notably Canto at Marina Bay, differed from the Mandopop and Cantopop joints of the 1970s in catering to the young fans of Hong Kong celebrity singers rather than to ageing Chinese businessmen.

Meanwhile, the concept of discotheque reached new heights when nightlife veteran Deen Shahul launched the teenage-friendly disco Fire in Orchard Plaza in 1989 and Singapore’s biggest discotheque, Sparks, in Ngee Ann City in 1993. At their peak, Fire had branches in Indonesia and Malaysia, while Sparks occupied the entire seventh floor of Ngee Ann City and came equipped with separate arenas for different music genres as well as some 30 karaoke rooms.

While none of these discotheques of yesteryear have survived, their legacies – from state-of-the-art sound and lighting systems to over-the-top and in-your-face interior designs – continue to influence those that followed in the years to come.

Top Ten Discotheque in Orchard Towers, c. 1985. Singapore Tourism Board Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Top Ten Discotheque in Orchard Towers, c. 1985. Singapore Tourism Board Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Researcher and writer Tan Chui Hua has worked on various projects documenting the heritage of Singapore, including a number of heritage trails and publications.

Researcher and writer Tan Chui Hua has worked on various projects documenting the heritage of Singapore, including a number of heritage trails and publications.

NOTES

-

Chen, N.F. (1971, October 16). Discotheque. New Nation, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Yong, J. (1966, February 27). Debut with a frug, a shake, a twitch and a scratch. The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Teo, K.G. (Interviewer). (2013, February 13). Oral history interview with Ronald Goh Wee Huat. [MP3 recording no. 003790/6/1]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Fireplace closed down on minister’s orders. (1969, March 21). The Straits Times, p. 24. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Police raid on discotheque: Six arrested. (1969, March 25). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

1am Trudeau. (1971, January 20). New Nation, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Crowds pack in at new ‘disco’. (1971, March 16). New Nation, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, T. (1970, September 16). No glam profits in a disco. The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

It’s a livotheque. (1971, September 22). New Nation, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 16 Sep 1970, p. 12. ↩

-

Barbarella Discotheque: Where the good times really are! (1970, January 3). The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; The Straits Times, 16 Sep 1970, p. 12. ↩

-

Kwee, M. (1971, January 30). Rajaratnam for today’s ‘dedication ceremony’. The Straits Times, p 17; Décor meets the modern standards (1971, April 23). The Straits Times, p. 45. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 16 Sep 1970, p. 12; Ong, P. (1973, February 10). X’Quisites make it to the nightclub scene. New Nation, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG ↩

-

The Straits Times, 16 Sep 1970, p. 12. ↩

-

Rediffusion was Singapore’s first cable-transmitted, commercial radio station, which began broadcasting in 1949. ↩

-

Mobile disco gets into the beat. (1982, September 12). The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

S’pore gets first mobile discotheque. (1970, September 20). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lee, P. (Interviewer). (2002, February 20). Oral history interview with Larry Lai [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 002625/14/9, p. 100]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Lee, P. (Interviewer). (2002, February 20). Oral history interview with Larry Lai [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 002625/14/8, pp. 92–94]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Larry Lai, 20 Feb 2020, p. 102. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Larry Lai, 20 Feb 2020, p. 105. ↩

-

Lee, P. (Interviewer). (2002, March 15). Oral history interview with Mike Ellery [MP3 recording no. 001989/4/4]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Wong, M.W.W. (Interviewer). (2010, May 25). Oral history interview with Amir Samsoedin [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 003521/5/5, pp. 262, 265]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; Ong, P. (1976, June 18). Dee-Jay Brian gets his mobile disco going. New Nation, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Mike Ellery, 15 Mar 2002. ↩

-

Richmond, B. (2002). The golden age of Singapore disco. Retrieved from MusicSG. ↩

-

Higher licence fees for discos planned. (1973, October 27). New Nation, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Higher tax for clubs and discotheques. (1971, May 12). New Nation, p. 3; Har, N. (1971, November 18). ‘Close at 1 am’ shock for night clubs. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

‘High flyers’ who make the scene in coffee houses, discos and bowling alleys. (1972, July 9). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Raman, P.M., & Pereira, G. (1973, October 23). Discos tighten up entry rules after warning by minister. The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ahmad Osman. (1973, November 18). Discos lose liquor permits. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chandran, R., & Pereira, G. (1973, November 2). Govt shuts down 6 discos. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

D’Rose, R. (Interviewer). (1996, February 28). Oral history interview with Mervyn Nonis [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001737/11/3, p. 63]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Final goodbye to the discos. (1973, December 14). New Nation, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Boiler Room disco closes down. (1973, October 31). The Straits Times, p. 1; Final goodbye to the discos. (1973, December 14). New Nation, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

[Oral history interview with Mervyn Nonis]https://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/flipviewer/publish/d/d9222956-115e-11e3-83d5-0050568939ad-OHC001737_003/web/html5/index.html), 28 Feb 1996, pp. 68–70. ↩

-

Govt eases curbs on nightclubs and discos. (1975, February 15). The Straits Times, p. 7; Disco to close shop again. (1977, June 24). New Nation, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Dance fever to catch on as disco contest begins (1979, July 5). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Santa the disco dancer. (1979, December 24). The Straits Times, p. 26. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Dhaliwal, R. K. (1975, October 17). The YMCA disco. New Nation, p. 2; Contest to pick the first disco queen. (1978, June 19). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Saturday night flu, anyone? (1979, November 17). New Nation, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ong, C. (1986, February 7). Another mammoth police disco night. The Straits Times, p. 17; For this disco, bring along a hongbao. (1986, February 5). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, T. (1970, September 16). No glam profits in a disco. The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ong, P. (1973, February 10). X’Quisites make it to the nightclub scene. New Nation, p. 7; Singapore’s young musicians come of age. (1971, August 30). New Nation, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chua, M., & Pereira, G. (1973, November 3). Discos may open again, but no music or dancing. The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

New Nation, 30 Aug 1971, p. 9. ↩

-

Har, N. (1971, March 27). Lousy bands or good records? The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩