Encountering Evidence in the Archives (In Many Ways and of Many Things)

Who would have thought that obscure rainfall records from the 1960s would have a bearing on a landmark case before the International Court of Justice? Eric Chin explains the value of archival records in preserving and presenting evidence.

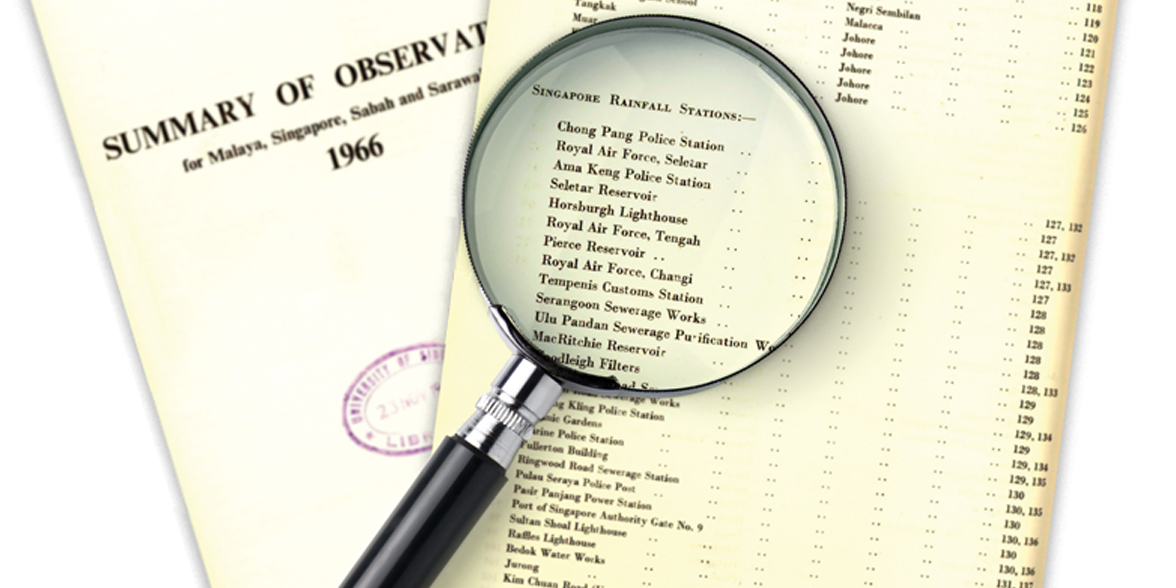

Horsburgh Lighthouse on Pedra Branca island is clearly listed as a Singapore Rainfall Station on page 4 of the report, Meteorological Services Malaysia and Singapore: Summary of Observations for Malaya, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak 1966. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Horsburgh Lighthouse on Pedra Branca island is clearly listed as a Singapore Rainfall Station on page 4 of the report, Meteorological Services Malaysia and Singapore: Summary of Observations for Malaya, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak 1966. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.– Anne Gilliland, Archival Science, September 20101

Archivists and those who use the archives for research work may be familiar with the well-known adage that archives are “about acquiring, describing and preserving documents as evidence”.2

This was most powerfully demonstrated in the resolution of the Pedra Branca dispute in 2008 by the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Prof S. Jayakumar and Prof Tommy Koh were unanimous in their view that the legal team “would not have the materials with which to write the written or oral pleadings”3 without the help of the National Archives of Singapore (NAS). At the end of the court proceedings, the judgment of 23 May 2008 on Pedra Branca (ICJ Judgment)4 was granted in Singapore’s favour. The NAS would go on to receive the President’s Certificate of Commendation in November that year for its “outstanding team work and contributions towards the successful resolution of the Pedra Branca dispute”.

The same honour was bestowed on the NAS some 10 years later on 28 October 2018 for “outstanding teamwork and contributions in defending Singapore’s sovereignty and national interests”, as part of an Inter-Agency Pedra Branca Team, when Malaysia filed an application at the ICJ on 2 February 2017 to review the judgment made in 2008.5

Evidence in the Everyday

– Arlette Farge, 19896

How was the day won? The ICJ Judgment stated the basic legal principle on the burden of proof – “a party which advances a point of fact in support of its claim must establish that fact”.7 The key facts cited in the judgment were established through evidence found in diverse archival records, such as correspondences, official memos, reports and maps. These were compiled from the archival holdings of the NAS and other Singapore public agencies as well as from overseas archives.

Together, the documents provided a wealth of evidence testifying that Singapore’s actions were wholly consistent with the exercise of ownership, such as the exercise of control on who could visit Pedra Branca. Notably, the ICJ Judgment specifically highlighted the converse as well: the absence of any archival evidence of actions presented by Malaysia to contradict Singapore’s position.8

An 1851 painting of the gunboat Nancy and Horsburgh Lighthouse on Pedra Branca by John Turnbull Thomson, Government Surveyor for the Straits Settlements. Nancy sailed from Malacca and arrived at Pedra Branca on 1 May 1848 to combat piracy in the area. The lighthouse was designed by Thomson and completed in 1851. It is named after James Horsburgh, a hydrographer with the British East India Company. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

An 1851 painting of the gunboat Nancy and Horsburgh Lighthouse on Pedra Branca by John Turnbull Thomson, Government Surveyor for the Straits Settlements. Nancy sailed from Malacca and arrived at Pedra Branca on 1 May 1848 to combat piracy in the area. The lighthouse was designed by Thomson and completed in 1851. It is named after James Horsburgh, a hydrographer with the British East India Company. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.In a case where the legal examination of the facts went all the way back to the 1800s, the heavy reliance on documentation provided by the NAS and other archives was to be expected. What was more surprising was that most of the archival records that eventually found their way into bundles of evidence for scrutiny were bureaucratic records created in the course of everyday business – received and dutifully kept as ordinary records of seemingly little national or historical significance. It is fair to say that the many who produced or filed away these archival records, some from over a century ago, could not have anticipated how they would come to be used one day.

Among the archival records that made a surprise appearance before the ICJ was a letter from the American Piscatorial9 Society dated 17 June 1972, requesting permission to undertake research in the waters surrounding Pedra Branca. There were also meteorological publications on rainfall that were held as “significant in Singapore’s favour”: the inclusion of Horsburgh Lighthouse as a “Singapore” station in 1959 and 1966 when such information was jointly reported by Malaysia and Singapore and, more significantly, its omission from the 1967 Malaysian report “when the two countries began reporting meteorological information separately”.10

It is clear that the value of the evidence contained in an archives is not always fully realised at the point of its creation. It is the role of the archivist to see a bigger picture, the ability to see beyond the immediate purpose and use of a document.11

“Archives are not a static artefact imbued with the creator’s voice alone, but a dynamic process involving an infinite number of stakeholders over time and space.”12 Those in the archives community are only too aware that archives are “always in a state of becoming”,13 as different people can view and interact with the same archival records from different perspectives and contexts at different times. This being the case, the value of the evidence contained in the archives is not confined to its use in legal proceedings alone.

Beyond Judicial Evidence

We can take a leaf from the Australian Society of Archivists, which has posited that the mission of the archivist is “to ensure that records that have value as authentic evidence of administrative, corporate, cultural and intellectual activity are made, kept and used”.14 This positions “evidence” as the constant at the heart of the archives but it also touches on the fact that the archives may be valued for different reasons, from the bureaucratic and organisational to the cultural, from being symbols of national pride to those of a community and the personal.

As the NAS entered its 50th year in 2018, it is apt that it can offer much for those wishing to cast a renewed eye on our history during this bicentennial year (marking Stamford Raffles’ arrival in Singapore). A multi-faceted archives can offer varying insights for diverse people, from historians interested in serious post-colonial discussions to those simply wanting to discover nuggets of interesting sights and sounds of the times.

A first stop when looking at NAS’ holdings relevant to the bicentennial must be what has become known as the Straits Settlements Records (SSR), which date back to the year 1800 and charts the history of the British administration in Singapore as well as the Malay Peninsula. Among these records are Raffles’ proclamations and his letters of instruction on the administration of Singapore.

A well-known example of Raffles’ influence on Singapore’s development is the six “Regulations” issued by him despite not having the legal authority to do so. More recently uncovered alongside the substantive parts of the regulations are his common-sense instructions for their dissemination. Apart from the original versions in English, Raffles astutely directed that the regulations be translated into both Malay and Chinese. He also directed that they “be published by beat of gong and affixed to the usual places for public information”. The use of the gong in lieu of the bell rung by a typical English town crier was at the very least practical; or perhaps it was simply a nod to local culture.

The NAS has come to learn a lot more about the contents of the early handwritten SSRs through the tremendous efforts of members of the public. These “citizen archivists”, as they are known, have steadily transcribed the manuscripts into searchable text since the voluntary project began in 2015. To date, more than 28,000 pages of the SSR have been transcribed to reveal a vast amount of new knowledge.

For instance, in the proclamation made under the direction of Raffles dated 14 March 1823, the transcription revealed that Raffles’ sense of British justice for serious crimes included the rather protracted punishment where the body of an executed murderer is “hanged in Chains and given to the winds”.15 We now know from our own archives that dramatic movie scenes of hanging skeletons were very much true to life back in the day.

Raffles’ Regulations III and VI set up a nascent magistracy, and the first notions of British-style justice was practised in Singapore until formal ties with English courts were cut in 1994.16 The reception of English law and its courts were formally confirmed in the Charters of Justice. The original copy of the 1855 Third Charter of Justice has been preserved by the NAS and is currently on display at the NAS exhibition, “Law of the Land: Highlights of Singapore’s Constitutional Documents”, at the former Chief Justice’s Chamber and Office, National Gallery Singapore.

The Third Charter of Justice provided for the post of the very first professional judge to be permanently located in Singapore – evidence of the island’s growing commercial and administrative importance by that time. Citizen archivist transcriptions, however, have provided evidence that the British did not necessarily have blind faith in their methods alone.

Another citizen archivist transcription revealed that on 16 April 1862, long before the 1990s push towards “Singapore law to develop in a way most suited to its people’s needs”,17 then Governor of the Straits Settlements William Orfeur Cavenagh voiced serious misgivings about magistrates fresh from the English Bar who possessed scant local knowledge. In a letter addressed to the Secretary to the Government of India, he wrote:

“I am unable to agree… as to the propriety of selecting Magistrates from the English Bar without any reference to local knowledge; although most readily acknowledging all the great advantages of a legal education as fitting its recipient for the performance of legal duties. I have long considered that a knowledge not only of the languages, but of the general character and habits of Orientals is not merely essential but absolutely necessary to enable an Englishman to satisfactorily dispense justice amongst our Asiatic fellow subjects.”18

2019 also sees the 60th anniversary of an event on the other end of the colonial era. In 1959, Singapore achieved self-government with an elected 51-seat Legislative Assembly. The positions of Governor and Chief Minister would be replaced with the Yang di-Pertuan Negara (Head of State) and Prime Minister respectively. In the run-up to the election that took place on 30 May 1959, the importance of voting was emphasised through colourful posters and election songs,19 encouraging people to “vote to choose our government” as “Singapore is ours”.

A poster from the 1959 Legislative Assembly general election encouraging people to “vote to choose our government” as “Singapore is ours”. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

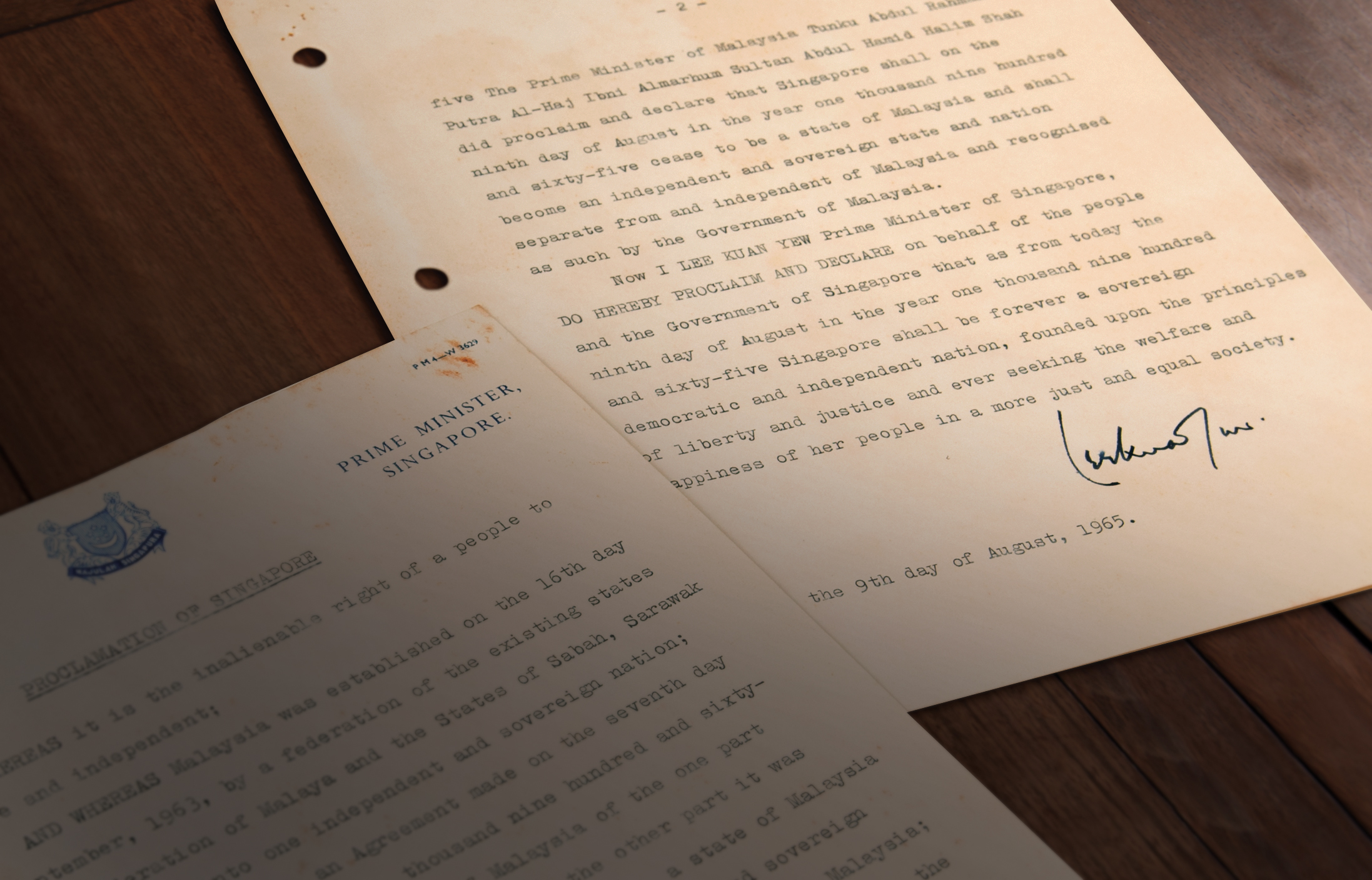

A poster from the 1959 Legislative Assembly general election encouraging people to “vote to choose our government” as “Singapore is ours”. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The posters and songs preserved by the NAS serve as part of the evidence of the sights and sounds of an important but turbulent period, culminating with the archival document that has been imbued with symbolic value – the hastily typewritten Proclamation of Singapore in 1965.

Evidence from Beyond Singapore

Apart from holdings transferred from other government agencies, NAS has for a long time been active in securing Singapore-related content from overseas archives. Unlike in ancient times, no single archive can claim to be the only “repository of both knowledge and proof in its day”.20 Chief among the “foreign archives” that the public can access at the NAS Archives Reading Room are copies of “Migrated Archives”21 relating to Singapore from The National Archives in the United Kingdom.

The typewritten Proclamation of Singapore document signed off by founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew on 9 August 1965. This is another key document in the holdings of the National Archives. Courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

The typewritten Proclamation of Singapore document signed off by founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew on 9 August 1965. This is another key document in the holdings of the National Archives. Courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.These records from former British colonies were kept by the Foreign & Commonwealth Office and had not been available for public access until they were released in tranches from 2012. Similar records from the national archives of Australia and the United States have also been identified (and copied where permitted) as they provide different strands of evidence of Singapore’s colonial and post-colonial past as well as alternative perspectives of historical events. Through such steady work, the NAS seeks to be the primary and one-stop repository of Singapore content when it comes to archives from anywhere in the world.

Oral History as Evidence

– Kwa Chong Guan & Ho Chi Tim, 201222

Instead of being cautious about treating oral testimony as evidence, the NAS sees the use of oral history and other forms of archives (apart from the textual) as the “path to a rich and nuanced understanding of events and actions”.23 There has been a recent turning away by archivists and historians from the traditional reliance on textual records. There is a growing realisation that the purely textual is “not sufficient for all cultures and places”,24 although the NAS has always proudly championed oral history through its Oral History Centre. In words co-authored by noted historian and former director of the Oral History Centre, Kwa Chong Guan,25 the oral history recording programme was “in effect creating an archival record of the circumstances of Singapore’s creation and development”.

The NAS’ long-time practice of drawing out concrete evidence as well as subtle nuances from key actors in events that have shaped Singapore and those who experienced the events first-hand and have a story to tell, has become the current refrain of many an archival theorist: “where documentary gaps exists… archivists should actively intervene with documentary projects such as oral histories… to create a ‘record’ that fills in the missing experience or knowledge”26 or indeed, the eye witness accounts (i.e. evidence) of happenings.

Such was indeed required in the case of Singapore’s collective memory of the Japanese Occupation27 where local records were all but destroyed. Where gaps have been less serious, oral history and archives in the form of photographs and audiovisual archives have also “contribute[d] to bringing to life individuals and communities that (may) otherwise lie rather lifeless or without colour in the paper record”28 alone.

The Keepers of Evidence

– James M. O’Toole & Richard J. Cox, 200629

It would be remiss when speaking of evidence in the archives not to pause and recognise that archivists, historians and other researchers are now painfully aware that archives can sometimes only offer an “archival sliver”.30 This may be partly attributed to the “avalanche of over documentation” (starting as far back as the mid-20th century31 and especially now in the digital age). Besides the indiscriminate disposal or deliberate destruction by creators of records,32 large gaps in archival records can also stem from careless appraisal methodologies or biases,33 the exclusion of the marginalised,34 and also the sheer failure by some to record transactions because of ignorance or deliberate acts by those wanting to be forgotten.35

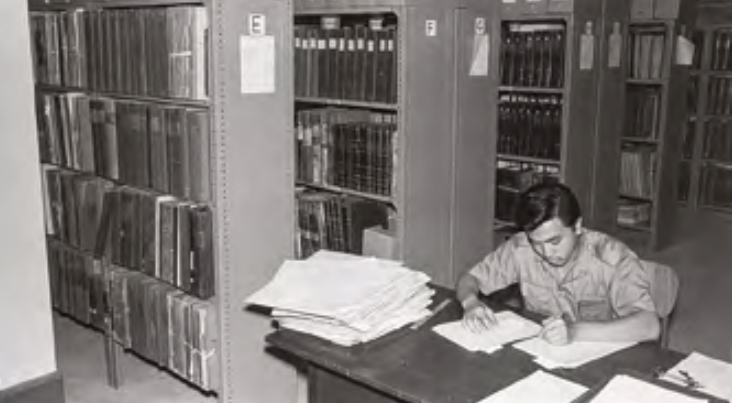

The wealth and reliability of evidence from any archive is ultimately shaped and nurtured by archivists, conservators and administrative staff who, together, have to apply sound archival ethics, policy, preservation and standards.36 This started in Singapore some 50 years ago in 1968, when the National Archives and Records Centre was set up as an institution with its own dedicated mandate and “one Senior Archives Officer; two Clerical Assistants; two Archives Attendants; one Typist; one Binder; one Office Boy”.

A typical staff workspace with simple wooden desk and chair amongst the archives at the National Archives and Records Centre at Lewin Terrace, 1971. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A typical staff workspace with simple wooden desk and chair amongst the archives at the National Archives and Records Centre at Lewin Terrace, 1971. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Despite the modest numbers, it was a good start not least because the senior archives officer was Lily Loh (later Mrs Lily Tan), the first professionally trained archivist who would later be appointed director of the NAS from 1978 to 2001. She and her team of dedicated staff expanded operations to establish the first Oral History Unit, the first Audiovisual Archives Unit, and oversaw the move to the NAS’ current location at Canning Rise with its purpose-built conservation equipment and repositories based on international standards.

Today, the staff of NAS continue to build on this solid bedrock to preserve and present archival records that offer what the French historian Arlette Farge has evocatively described as a tantalising “tear in the fabric of time”.37

Eric Chin is the General Counsel of the National Library Board. He was formerly Director of the National Archives of Singapore (2012–17).

Eric Chin is the General Counsel of the National Library Board. He was formerly Director of the National Archives of Singapore (2012–17).

NOTES

-

Gilliland, A.J. (2010, September). Afterword: In and out of the archives. Archival Science, 10 (3), 333–343, p. 334. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Cook, T. (2013, June). Evidence, identity, memory, and community: Four shifting archival paradigms. Archival Science, 13 (2–3), 95–120, p. 97. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Jayakumar, S., & Koh, T. (2009). Pedra Branca: The road to the world court (p. 63). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 341.448095957 JAY) ↩

-

International Court of Justice. (2008, May 23). Sovereignty over Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks and South Ledge (Malaysia/Singapore), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports. Retrieved from the International Court of Justice website. ↩

-

Malaysia withdrew its application on 28 May 2018. On 29 May, the ICJ informed Singapore and Malaysia that the case would be removed from the court’s list. The judgment of 23 May 2008 still stands. ↩

-

Farge, A. (2013). The allure of the archives (T. Scott-Railton, Trans.) (p. 7). New Haven: Yale University Press. (Original work published 1989). (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

International Court of Justice, 23 May 2008, para. 45, p. 23. ↩

-

International Court of Justice, 23 May 2008, paras. 273–277, pp. 87–88. ↩

-

“Piscatorial” means “of or concerning fishermen or fishing”. Retrieved from Oxford Dictionaries. ↩

-

International Court of Justice, 23 May 2008, paragraph 266, pp. 85–86. ↩

-

O’Toole, J.M., & Cox, R.J. (2006). Understanding archives & manuscripts (p. 86). The Society of American Archivists. Chicago, IL: Society of American Archivists. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Ketelaar, E. (2012, March). Cultivating archives: Meanings and identities. Archival Science, 12 (1), 19–33, p. 19. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Gilliland, Sep 2010, p. 339. ↩

-

Australian Society of Archivists. (2019). The archivist’s mission. Retrieved from Australian Society of Archivists website. ↩

-

Raffles, T.S. (1823). L17: Raffles: Letters to Singapore (Farquhar). Retrieved from The Citizen Archivist Project website. ↩

-

Goh, Y. (2015). Law (p. 98). Singapore: Institute of Policy Studies and Straits Times Press. (Call no.: RSING 349.5957 GOH) ↩

-

Cavenagh, W.O. (1862, April 16). R44: Governor’s letters to Bengal (Judicial). Retrieved from The Citizen Archivist Project website. ↩

-

Radio Singapore. (1959, May 19). Election song. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Gilliland, Sep 2010, p. 334. ↩

-

Thomas, D., Fowler, S., & Johnson, V. (2017). The silence of the archive (pp. 5–6). London: Facet Publishing. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Kwa, C.G., & Ho, C.T. (2012). Archives in the making of post-colonial Singapore (p. 133). In C. Jeurgens, T. Kappelhof & M. Karabinos (Eds.), Colonial legacy in South East Asia: The Dutch archives. ’s-Gravenhage: Stichting Archiefpublicaties. (Call no.: RSEA 026.959 COL-[LIB]) ↩

-

Bastian, J.A. (2017). Memory research/archival research (p. 269). In A.J. Gilliland, S. McKemmish & A.J. Lau (Eds.), Research in the archival multiverse. Melbourne: Monash University Publishing (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Cox, J.C. (2009). The archivist and community (p. 254). In J.A. Bastian & B. Alexander (Eds.), Community archives: The shaping of memory. London: Facet Publishing. (Call no.: R 025.1714 COM-[LIB]) ↩

-

Kwa Chong Guan was Director of the Oral History Centre from 1985 to 1994. He has served as a board and advisory committee member of the NAS since 1993 and was Chairman from 2006 to 2015. ↩

-

Gilliland, Sep 2010, p. 336. ↩

-

Lee, G.B. (2017). Syonan: Singapore under the Japanese, 1942–1945. (pp. 11, 193). Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society and Landmark Books. (Call no.: RSING 940.535957 LEE) ↩

-

Thomas, D., Fowler, S., & Johnson, V. (2017). The silence of the archive (p. 18). London: Facet Publishing. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

O’Toole, J.M., & Cox, R.J. (2006). Understanding archives & manuscripts (p. 146). Chicago, IL: The Society of American Archivists. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Harris, V. (2002, March). The archival sliver: Power, memory, and archives in South Africa. Archival Science, 2(1), 63–86, p. 63. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Cook, Jun 2013, p. 101. ↩

-

Harris, Mar 2002, p. 64. ↩

-

Cox, R.J. (2004). No innocent deposits: Forming archives by rethinking appraisal (pp. 176–180). Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. (Call no.: R 025.21 COX-[LIB]) ↩

-

Thomas, Fowler & Johnson, 2017, p. 4. ↩

-

30 Year Rule Review. (2009, January). Review of the 30 year rule. Retrieved from 30 Year Rule Review website. ↩

-

Duranti, L., & Franks, P.C. (Eds.). (2015). Encyclopedia of archival science. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Farge, 2013, p. 6. ↩