Stories of the Little People

Oral history is often considered as “little” – personal accounts of humble folk, as opposed to “big” or written history on serious topics. But “little” does not mean negligible or inferior, says Cheong Suk-Wai.

If you delve into the Oral History Centre (OHC)’s trove of some 4,900 interviews with Singaporeans and foreigners of diverse backgrounds, you will encounter one constant – the following disclaimer that prefaces every interview transcript:

“Readers of this oral history memoir should bear in mind that it is a verbatim transcript of the spoken word and reflects the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. Oral History Centre is not responsible for the factual accuracy of the memoir, nor for views expressed therein; these are for the reader to judge.”

This disclaimer is necessary as oral history accounts could fuel lawsuits arising from family or business feuds or, if the interviewee’s memory is foggy, suggest what is actually wrong as right. Worse still, if interviewees deliberately lie in their accounts, leading those who assume the untruth as fact down the garden path.

Alas, such a disclaimer can deter prospective users from the OHC’s collection. After all, they might wonder: “Why should one pore through a story that might be riddled with factual inaccuracies?”

For this reason, some people who plumb history for a living have traditionally looked askance at oral history, believing its interviewees to have less veracity, ergo, their interviews to be of less value than written history simply because the interviewees are relying on memory and therefore prone to give vent to their feelings and emotions in recalling incidents in the past.

Learning

Those critical and disdainful of oral history tend to view it as being little better than gossip, rumours and tall tales, which were all grist for the graffiti on the walls of ancient Rome, as British journalist Tom Standage documented in his book, Writing on the Wall: Social Media, the First 2,000 Years. Yet, as Standage noted, such brazen communications were what ultimately kept all levels of society on the same up-to-date page, thus enabling Roman society to be open, informed and thriving.1

But while it is wise to be circumspect about the authenticity of an oral history account, it does not mean that an oral account in itself is unreliable or, worse, inferior to the written text. If it was so, then why does a witness’s oral testimony in a court of law still hold water and, indeed, sometimes become the deciding factor on whether an accused person in the dock gets to live or die?

Those who deride the value of oral testimony against written or printed accounts would do well to take a leaf from The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire Trial. This fire that took place in a garment factory broke out on 25 March 1911 in the 10-storey Asch Building off Washington Square in New York City. It killed 146 people, most of whom were factory employees who had jumped through the building’s windows to their deaths because the factory’s escape door was locked.

The fire is considered one of the worst industrial accidents in American history. The factory’s owners were put on trial between 4 December and 27 December 1911 for manslaughter. Their lawyer Max David Steuer – who, like the factory employees, was an immigrant in America – succeeded in getting them acquitted by demolishing the credibility of the prosecution’s star witness, Kate Alterman.

Steuer did so by making Alterman, who was illiterate, repeat four times in court her account of how her friend Margaret Schwarz died in the fire. Each time Alterman retold her story, she rehashed faithfully evocative phrases such as “curtain of fire” and described a man in a panic as being “like a wildcat”. It soon dawned on the jury that the prosecution had likely made Alterman commit to memory a written account of the fire as the prosecution believed it to be.

The trial turned on the question as to whether the factory’s owners knew that the escape door had been locked. Through his relentless cross-examination of Alterman, Steuer cast enough doubt on what she described of the fire to absolve his clients. Thus, putting down certain assertions on paper – as what the prosecution did in this case – does not in and of itself make those assertions any more verifiable and authoritative than oral testimony.2

The greater trust in textual as opposed to oral historical sources these days is even more befuddling when you consider that humankind has, for the better part of its 300,000 years on earth, used the oral tradition to pass down the roots of their tribes, their family trees, chronicles of births, deaths, wars and conquests, and how territories changed hands over time.

Writing in the magazine History Today in 1983, British sociologist and oral historian Paul Thompson3 noted that early societies that could not read or write made storytellers their “tradition-bearers”. For example, he points out that “the griots of African villages recite by heart the genealogies of landholding”, as do the Chinese of dynastic succession or community roll calls of natural as well as political disasters.4

Thompson further noted that even after humankind became literate, its intellectual luminaries still had great regard for oral accounts. Among them was the Greek historian Herodotus (c. 484 BC– c. 425 BC) and the French man of letters Voltaire (the pseudonym of Francois-Marie Arouet). Voltaire (1694–1778), who was as cynical as they come, wrote his biography of France’s Sun King, Louis XIV, after interviewing those who knew the monarch well. No less than Samuel Johnson (1709–84), the English moralist and a literary lion like Voltaire, praised the latter’s collation of oral testimonies on the Sun King.

Thompson demonstrated that professional historians and top thinkers have long used oral testimonies that uphold strong, scholarly standards.

Valuing

Now, if we accept that oral testimonies are valuable, just what about them is so valuable then? Well, to begin with, such interviews offer us rich, layered perspectives of people from all walks of life that simply cannot be replicated by textual sources because the latter format is founded on structure and objectivity, not serendipity and epiphanies.

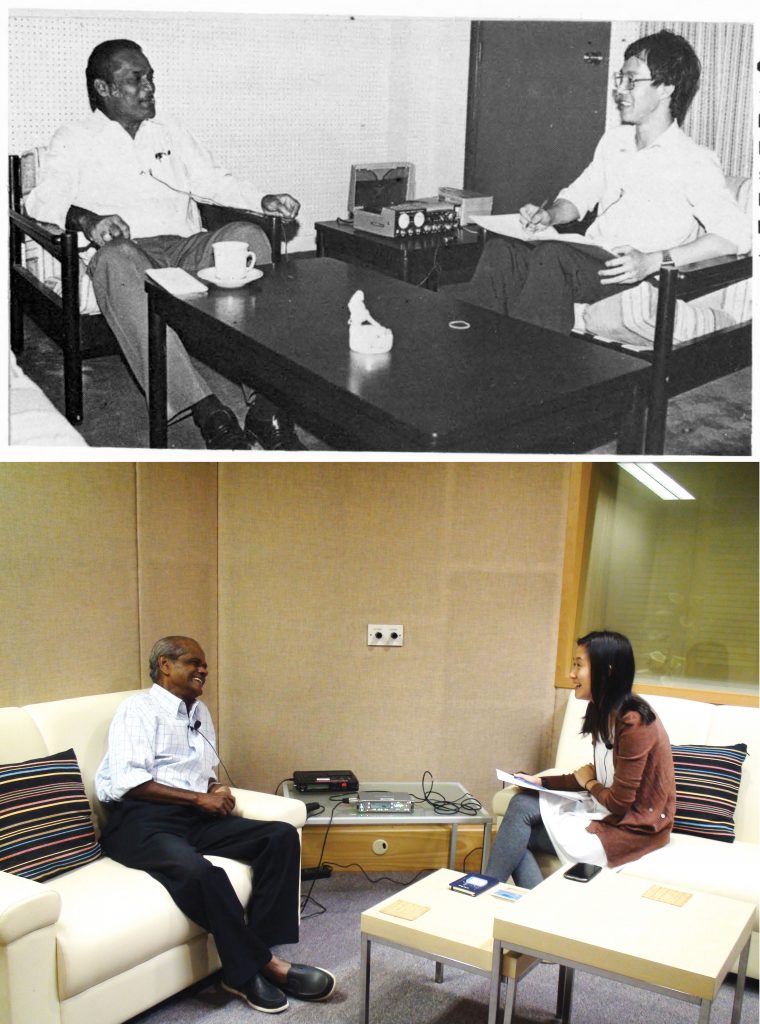

An oral history interview conducted in the 1980s (top) and one carried out in the 2010s (bottom). The basic techniques of conducting an oral history interview remain largely the same. However, the recording equipment used has changed significantly. In the 1980s, interviews were recorded using high-fidelity reel-to-reel tape recorders and open-reel tapes. These tapes typically could only record 30 minutes on each side and required special care to prevent deterioration. Today, digital recorders and flash memory cards provide better sound quality, allow for longer recordings and are more compact and easier to preserve. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

An oral history interview conducted in the 1980s (top) and one carried out in the 2010s (bottom). The basic techniques of conducting an oral history interview remain largely the same. However, the recording equipment used has changed significantly. In the 1980s, interviews were recorded using high-fidelity reel-to-reel tape recorders and open-reel tapes. These tapes typically could only record 30 minutes on each side and required special care to prevent deterioration. Today, digital recorders and flash memory cards provide better sound quality, allow for longer recordings and are more compact and easier to preserve. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The importance of having the perspectives of oral history, however, becomes clear when, for example, you compare two accounts about the areas in Singapore that were targeted by Japanese fighter pilots in the days leading to the fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942. The interviewee in the first account who, understandably shall remain unnamed in this instance, said that the Japanese shelled the Cathay Building off Orchard Road because it was the tallest building in Singapore then.

Veteran journalist Khoo Teng Soon, however, recalled otherwise in his oral history interview:

“In those days, the tallest building in Singapore was the Cathay Building. And that used to be the landmark for the Japanese. They never bombed the Cathay Building because it was a very useful building for them to know their bearings. They knew that once they flew over the Cathay Building, they were on their way to any spot they wanted to bomb.”5

Cathay Building on Handy Road, 1941. During the Japanese Occupation, the building housed the Japanese Broadcasting Department, Military Propaganda Department and Military Information Bureau. Cathay Building was gazetted as a national monument on 10 February 2003. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Cathay Building on Handy Road, 1941. During the Japanese Occupation, the building housed the Japanese Broadcasting Department, Military Propaganda Department and Military Information Bureau. Cathay Building was gazetted as a national monument on 10 February 2003. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Khoo should know. He worked in that very building for wartime Japan’s Domei (now Kyodo) information agency.

Similarly, the availability of a variety of views on a historical event lends its context greater definition, colour and, most importantly, nuances. A fuller context, then, gives readers a fuller and firmer grasp of a particular period in the past. For example, in his oral history interview, former Director of Education Chan Kai Yau lamented how, as a boy in the 1930s, he hardly played with his friends after school because he had to queue for hours just to buy a precious loaf of bread – which was very light, brown and did not taste of much.6 His compatriot Mrs Gnanasundram Thevathasan, a former Justice of Peace, backed up his recollection by recounting how everyone made cakes from rice flour because wheat was too expensive for most households then.7

It was ironic, then, that the onset of the Japanese Occupation in February 1942 brought with it a seemingly abundant supply of wheat flour to Singapore. Chan Kwee Sung, a columnist for The Straits Times between 1998 and 2002, and the author of One More Story to Tell: Memories of Singapore, 1930s–1980s,8 recalled that the Japanese distributed so much wheat flour as rations that “at almost every corner of Chinatown, you would find a wanton noodle stall because of the abundant supply of flour”.9

Or take Muslim Religious Council of Singapore pioneer Haji Mohamed Sidek Bin Siraj’s account of how people fleeing China began settling in Kampong Glam, which was predominantly Malay, from the 1920s. The casual observer might assume tension among the communities there from then on, but Haji Mohamed Sidek clarified as follows:

“They didn’t come in hordes. They just opened sundry shops… and they acquired the Malay language. And as shopkeepers in Jalan Sultan, they catered to the satay sellers who were Javanese. The Chinese there could speak Javanese too.”10

Experiencing

Beyond a greater understanding of how Singaporeans evolved amid changing circumstances, the vivid, personal insights afforded by oral history allow readers to experience the force of the very human drama that is real life. Plastic surgeon Lee Seng Teik, for one, recounted effectively the horrors of the Spyros ship explosion – still one of the worst industrial accidents in Singapore history – when he recalled “truckloads” of victims arriving at the Singapore General Hospital’s newly minted Accident & Emergency wing on 12 October 1978. He said:

Injured victims being rushed to hospital after an explosion and fire on board the Greek oil tanker, S.T. Spyros, on 12 October 1978. Seventy-six people died and 69 others were injured in the accident. Ministry of Health Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Injured victims being rushed to hospital after an explosion and fire on board the Greek oil tanker, S.T. Spyros, on 12 October 1978. Seventy-six people died and 69 others were injured in the accident. Ministry of Health Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.“I was to meet an officer, Dr Kenneth Cheong, who was supposed to give a talk that day. But at 2 pm, we had the very first indication of disaster… someone notified everyone of the possibility of a major disaster and to get ready.

“The meeting with Kenneth was off. Within half an hour, the first casualties arrived. We knew we had a true disaster – the casualties were in truckloads, lorries, not ambulances because there were too many casualties.

“As a director, I had never seen anything like it and, hopefully, will never experience that again.”11

Lee and his colleagues worked “flat out” for three days, trying to cope with the onslaught of burn victims. “We didn’t go home for three days,” he added. “I almost passed out on my way home after three days.”

Those who have documented such tragedies in their writing sometimes leave gory details out. But an oral history interviewee, when asked to tap his memory on that, would invariably say what they see in their mind’s eye – and the more articulate the interviewee, the more graphic, or nuanced, the account is likely to be. The difference between an oral history account and a textual one, then, is the difference between a fully fleshed-out portrait of a person and a stick figure sketch of him. In this way, oral history not only fills in the gaps from details omitted in written form, but restores the highlights and shadows of the past.

The historian’s work is often like that of a detective; they both track down truths of the past. And the greater the range of critical clues they have, such as those provided by the “I was there” insights of oral history, the better their chances of getting to the bottom of what, where, why and how something actually happened.

Now, you might ask, why should that matter? Why should one dig out such details about a person’s past? Mark Wong, Senior Specialist of Oral History at OHC, has a good answer to that. In an interview with me for my upcoming book on OHC’s 40th anniversary, Wong said: “History is why we are in this building now, why the chairs we are sitting on are shaped this way, why we are wearing shirts and jackets and trousers.” Or, as the aforementioned Paul Thompson noted in his book, The Voice of the Past, the value of all history is its “social purpose”, which is about helping everyone make sense of the present by understanding what shaped it.12

Singapore’s Speaker of Parliament Tan Chuan-Jin said as much in his reflection on Singapore’s bicentennial year in The Straits Times on 13 February 2019. “As a former student of history”, Tan wrote, “I do often consider: What if no one saw our potential as a landing point, a site for trade and exchange, a home? What if we hadn’t appeared useful, to anyone? What if the economic issues of the time had tripped us up along the way? Or the weight of commerce had shifted and rendered our geopolitical position worthless?”

He added that “little history, the local stories of people and communities” is as “vital” as “big history, the nation-building stuff”. If big and little histories are woven together, he added, that would give Singaporeans a better sense of who and where they are. “In an age of globalisation”, he noted, “our shared histories, memories and affections link us and give us relevance and access to so many places and people. And in those links too, we find common ground to move ahead, make progress.”13

Verifying

Those who prize fairness, balance, social justice and democracy would also find much to recommend about oral history. As noted earlier, most grand historical texts tend to record the accounts of winners, not losers. Oral history collections, on the other hand, are a great leveller: it is adamant that the lives of the gravedigger, the nightsoil carrier and the street opera actor matter as much for posterity as those of presidents, politicians and tycoons. Thanks to OHC’s dedicated interviewers, users of the collection can now say with confidence that they have access to a layered and multidimensional view of Singapore history.

Such a view is particularly relevant for Singapore society when you consider that many among its most accomplished, sometimes considered as society’s elite, actually had a keen grasp of how those on the ground had to live. Among them is James Koh Cher Siang, a former permanent secretary in the education, national development and community development ministries. An alumnus of Oxford and Harvard universities, he recalled how, as a boy, he was waiting at a bus stop with his schoolmates near Tiong Bahru when several fire engines whizzed past them. Koh recalled: “One of my friends told me, ‘Oh, maybe my house is on fire’. So we took a bus and rushed there and indeed, it was true, his house had burnt down.”14

All told, and in addition to OHC’s intellectual rigour and unstinting professionalism in preparing, conducting, assessing and processing its interviews, I have learnt three rules of thumb that could help determine the veracity of someone’s oral statements. These are:

1. Select the accounts of those who admit to what is of no conceivable benefit to them

People are wont to save their ego instead of saying sorry whenever apologies are due. So when someone shares something that would not put him in the best light, his account is more likely than not to be truthful. Writer Felix Chia, who escaped the Imperial Japanese Army’s execution of Chinese men during the Sook Ching massacre15 at the start of the Japanese Occupation in Singapore, recalled in his interview how he pilfered daily provisions meant for Japanese households. He would take along a tingkat, or tiffin carrier, every day and at 3 pm, when he and a Malay colleague divided up the spoils – deliveries of fresh meat, fish and vegetables for the Japanese – he would hide some of the food in his tingkat and take it home.16

Koeh Sia Yong’s oil painting titled Persecution (1963) showing innocent men dragged to execution grounds by Japanese soldiers. Operation Sook Ching, which took place in the two weeks after the fall of Singapore to the Japanese on 15 February 1942, saw thousands of Chinese men singled out for mass executions. According to some estimates, as many as 50,000 men died in the bloodbath. Courtesy of the National Gallery Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Koeh Sia Yong’s oil painting titled Persecution (1963) showing innocent men dragged to execution grounds by Japanese soldiers. Operation Sook Ching, which took place in the two weeks after the fall of Singapore to the Japanese on 15 February 1942, saw thousands of Chinese men singled out for mass executions. According to some estimates, as many as 50,000 men died in the bloodbath. Courtesy of the National Gallery Singapore, National Heritage Board.Then there is Vernon Cornelius, lead singer of The Quests, one of the most popular local bands in Singapore in the 1960s. Dubbed Singapore’s Cliff Richard, Cornelius recalled in his interview:

“I met Cliff Richard in Kuala Lumpur in 1995… I was embarrassed that my friend introduced me to Cliff Richard as ‘the Singapore Cliff Richard’. I felt like an idiot because we’re grown-ups now.”17

Vernon Cornelius (pictured on extreme right) lead singer of The Quests, was touted as Singapore’s Cliff Richard by the press. The Quests were formed in 1961 and went on to become one of the most successful bands of the era. May 1966. Photo by Peter Robinsons Studios, courtesy of Vernon Cornelius.

Vernon Cornelius (pictured on extreme right) lead singer of The Quests, was touted as Singapore’s Cliff Richard by the press. The Quests were formed in 1961 and went on to become one of the most successful bands of the era. May 1966. Photo by Peter Robinsons Studios, courtesy of Vernon Cornelius.2. Veer towards those who are able to recall happenings in specific detail

The more detailed a story, the greater the chances that it is true. Among the most popular entertainment game shows on British television today is Would I Lie To You? Now into its 12th season, it revolves around two teams of celebrities trying to decide if the yarn each is spinning is fact or fiction. Invariably, and unless they are habitual pathological liars, whenever participants are able to back up their story in great detail, they are most likely telling the truth.

In one uproarious instance – viewed 2,094,573 times on YouTube as at 14 February 2019 – the British comedian James Acaster claimed that Mick Trent, a 12-year-old guest on the show, was his “sworn enemy” after the boy put cabbage leaves in Acaster’s bed, causing an almighty stink. The comedian added that Mick later sent him a parcel in the post containing half a cabbage, wrapped in cling film. Acaster asserted further that his friends and fans began ribbing him about being “cabbaged” and took to hiding cabbages around his dressing room. “One even started a Twitter feed with the hashtag #OyOySavoy,” he huffed. As revealed later, every word he uttered was true.18

In contrast to this hilarious story, we have the disquieting OHC interview of a certain Social Welfare Department officer, whom I shall also not name here, on the likely cause of the ruinous fire at Bukit Ho Swee on 25 May 1961. The officer said: “I think it was some cooking utensil which, somehow or other, fell. And the whole place was a burning inferno in minutes because the place was all attap and wood.” His account on this point, which was already woefully short on details, trails off with no further mention of the alleged utensil. I should add that the actual cause of the fire was never determined.

Residents with their belongings gathering outside the fire area in Bukit Ho Swee on 25 May 1961. The fire, which razed a 0.4-sq km area consisting of a school, shops, factories and attap houses, was one of Singapore’s biggest fires. The fire left 16,000 kampong dwellers homeless and claimed the lives of four people. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Residents with their belongings gathering outside the fire area in Bukit Ho Swee on 25 May 1961. The fire, which razed a 0.4-sq km area consisting of a school, shops, factories and attap houses, was one of Singapore’s biggest fires. The fire left 16,000 kampong dwellers homeless and claimed the lives of four people. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.For my upcoming book on OHC’s 40 years, I combed through more than 300 complete oral history interviews in its redoubtable collection. I found most of these bracingly unvarnished, satisfyingly detailed and often heartfelt. One of the best examples of these attributes is the interview with Liak Teng Lit, who was the chief executive of Alexandra Hospital during the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) crisis in 2003.

My mother, who read excerpt from Liak’s interview in the first draft of my book, was in tears when she read of his recollection of how furniture store IKEA’s then general manager, Philip Wee, and his team set up beds in a disused building for a group of hospital nurses, with “compliments from IKEA for helping the country fight SARS”. That was right after the nurses’ landlords had kicked them out of their flats for fear that the nurses might infect them with SARS.19

3. Trust those who recall things in ways you yourself would

Often, what an oral history interviewee recalls instinctively rings true because that would be similar to how you would experience something yourself. This, of course, would depend on how much you have in common with an interviewee: age, gender and ethnicity, and your views on myriad issues all come into play. For example, Singaporeans of a certain age would nod knowingly to dramatist, writer and choreographer Richard Tan Swee Guan’s lament about how his aunt used to drag him to her favourite Hindustani film matinees, even though neither of them understood Hindi.20

And national servicemen today, who break off corners of their styrofoam lunchboxes to use makeshift spoons, would warm to Sally Liew’s account of how she and her colleagures shared packets of char kway teow (fried flat rice noodles). Liew, who was among the pioneering ground crew at Changi Airport, said they used the chits torn off boarding passes to scoop the noodles into their mouths when they did not have any cutlery to hand.21

This last point about how the same experiences can bridge generations would earn Paul Thompson’s approval. Noting how all history began with the oral tradition, and how people still enjoy accounts of lived experiences, Thompson’s sagely advice that “Oral history is the newest and oldest form of history” are words that all writers of history would do well to remember when they begin their research.

Cheong Suk-Wai’s book, The Sound of Memories: Recordings from the Oral History Centre, Singapore, based on the collection of the National Archives of Singapore’s Oral History Centre, was published by the National Archives and World Scientific Publishing in 2019. The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos. RSING 959.57 CHE and SING 959.57 CHE).

Cheong Suk-Wai is a lawyer by training and a writer by choice. A former ASEAN Scholar and Thomson Foundation Scholar, she has been a construction litigator, a journalist and a public servant.

Cheong Suk-Wai is a lawyer by training and a writer by choice. A former ASEAN Scholar and Thomson Foundation Scholar, she has been a construction litigator, a journalist and a public servant.

NOTES

-

Standage, Y. (2013). Writing on the wall: Social media, the first 2,000 years (pp. 38–42). London; New York: Bloomsbury. (Call no.: 302.2244 STA) ↩

-

Singapore. The Statutes of the Republic of Singapore. (1997, December 20). Evidence Act (Cap. 97, Section 146). Retrieved from Singapore Statues Online website. ↩

-

Paul Thompson graduated with a First Class Honours in Modern History from Corpus Christi College, Oxford University. He is a research professor at the University of Essex and in 1988 published the classic oral history textbook, The Voice of the Past. He has played a leading role in shaping the international oral history movement. ↩

-

Thompson, P. (1983, June 6). Oral history and the historian. History Today, 33 (6). ↩

-

Tan, L. (1984, October 4). Oral history interview with Khoo Teng Soon [Transcript of recording no. 000475/21/7, pp. 82–83]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Chua, J.C.H. (1995, November 7). Oral history interview with Chan Kai Yau [Transcript of recording no. 001707/36/3]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Pitt, K.W. (1984, November 14). Oral history interview with Thevathasan, Gnanasundram (Mrs) [Transcript of recording no. 000345/70/63, pp. 6–7]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Chan, K.S. (2005). One more story to tell: Memories of Singapore, 1930s–1980s. Singapore: Landmark Books. (Call no.: RSING 959.5705092 CHA-[HIS]) ↩

-

Chew, D. (1993, September 23). Oral history interview with Chan Kwee Sung [Transcript of recording no. 000692/11/6, p. 49]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Chew, D. (1991, May 29). Oral history interview with Mohamed Sidek bin Siraj (Haji) [Transcript of recording no. 001255/6/5, p. 2]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Lee, P. (2002, March 20). Oral history interview with Lee Seng Teik (Prof) [Recording no. 002632/11/6]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Thompson, P. (2000). The voice of the past: Oral history (p. 25). New York: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Tan, C.J. (2019, February 13). When history leaps from textbooks onto our streets and into our lives. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Lim, J. (2008, May 16). Oral history interview with Koh, James Cher Siang [Transcript of recording no. 002847/6/1, p. 13]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Sook Ching is a Chinese term meaning “purge through cleansing”. Operation Sook Ching was a Japanese military operation aimed at eliminating anti-Japanese elements from the Chinese community in Singapore. From 21 February to 4 March 1942, Chinese males between the ages of 18 and 50 were summoned to report at mass screening centres and those suspected of being anti-Japanese were summarily executed. ↩

-

Chou, C. (1994, September 1). Oral history interview with Felix Chia [Transcript of recording no. 001553/8/2, pp. 6–7]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Ruzita Zaki. (1995, December 20). Oral history interview with Cornelius, Vernon Christopher [Transcript of recording no. 001711/18/12, p. 140]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Mick – James Acaster’s arch enemy? Lee Mack’s traded toddler? Gabby Logan’s cheated child? (2017, December 4). Would I Lie To You? (Series 11, episode 3). Retrieved from YouTube. ↩

-

Tan, A, (2014, May 26). Oral history interview with Liak Teng Lit [Recording no. 003867/36/20]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Zaleha Bte Osman. (1999, April 14). Oral history interview with Tan, Richard Swee Guan [Transcript of recording no. 002108/8/7, p. 105). Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Lee, P. (2000, July 7). Oral history interview with Chan, Sally (Mrs) @ Sally Liew [Transcript of recording no. 002353/4/3, p. 33]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩