“I Hasten to Beg Your Indulgence…”: When Declassifying Can Also Mean Decoding

When the National Archives embarked on the declassification initiative to unlock documents previously labelled as “secret” and “confidential” for public access, it also had to decipher what was actually written, says K.U. Menon.

“Those who control the present, control the past and those who control the past control the future.”

George Orwell’s famous line from his dystopic novel 1984 is a sobering reminder of how important it is to be aware of the origins and sources of information we receive.

It is also a warning about the mutability of information. Through much of history, warring nations have plundered or destroyed the archives of other nations in their bid to expunge the identity of the vanquished. In World War II Europe, the Nazis looted not only art and historical treasures from the countries they invaded but also their precious manuscripts.

Singapore Policy History Project

These were some of the underlying concerns that led to the establishment of the Singapore Policy History Project (SPHP). Initiated by the Ministry of Communications and Information (MCI) just prior to Singapore’s 50th anniversary of independence in 2015, the SPHP proposed a framework for the systematic declassification of public records under the care of the National Archives of Singapore (NAS).

The intention is to gradually release information that will enhance Singaporeans’ understanding of the rationale behind certain government policies and how they have evolved. It is also about setting the record straight: declassifying previously inaccessible public records – including those categorised as “secret” or confidential”– will provide people with factual information on the political and historical development of Singapore.

In short, the declassification initiative will open up aspects of our history that were previously locked up and placed beyond the reach of the ordinary man in the street.

Many key decisions made in government today, for example, in relations with other countries and dealings with multilateral agencies, are based on assessments of personalities and precedents that go back many decades. For instance, in 2014, many Singaporeans did not grasp the gravity of the situation when Indonesia named two warships after the men who bombed MacDonald House in March 1965 until the historical context was made clear from archival records for all to see. In March 2015, there was a sense that many younger Singaporeans who stood in long queues to pay their respects to the late former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew were probably unaware of the extent of his contributions to the nation.

Citizens, researchers and academics, especially historians, have long been lobbying for greater access to our public records. Archival research is primary research based on substantive evidence from original archival records. It is a methodology used by researchers to collect data directly from the sources, rather than depending on data gleaned from previously published research.

Recognising the rights of citizens to access their own history, a National Museum exhibition in 2015 featured the very important declassified secret document known as the “Albatross File”. Belonging to one of Singapore’s founding fathers Dr Goh Keng Swee, the secret file offered insights into the negotiations leading up to separation from Malaysia in 1965. It was a defining moment in our history, and the exhibition included, among other things, handwritten notes of meetings with Malaysian leaders.

In an interview in 1980, Dr Goh admitted that the Albatross referred to Malaysia. He said: “By that time, the great expectation that we foolishly had – that Malaysia would bring prosperity, common market, peace, harmony, all that – we were quickly disillusioned. And it became an albatross round our necks.” This is the first time in history that the existence of the file was revealed to the public.

The MCI began the pilot phase of declassifying files under its purview in late 2013 with a team of researchers, including retired senior public officers, in the first-ever systematic declassification project undertaken in Singapore.

Interestingly, one of the things that struck the team while trawling through old documents from the late colonial and postcolonial period of our history was how the use of language in the civil service has evolved over the years. They were struck by the archaic and formal language, often liberally peppered with humour or sarcasm – and sometimes a blend of the two – employed by civil servants.

Language as a Weapon

For Britain, close to two centuries of colonial rule did not rest entirely on the might of its military forces. Britain also wielded power through other means, and language was a powerful weapon. Extending the use of the English language to the seemingly underdeveloped and backward colonies of Asia was seen as a way of bringing order, political unity and discipline to its colonies.

The British viewed its rule as a form of “autocratic nationalism”, and mandating English as the official language enabled it to monopolise public discourse and to impose arbitrary definitions on terms that framed British policy.1 As one scholar aptly observed, “colonial structures depended on native scaffolding”.2

One offshoot of that native scaffolding was Babu (or Baboo) English – a particularly florid, sometimes pompous and unidiomatic version of English incorporating extreme formality and politeness that was widely employed by administrators, clerks and lawyers in India. “Babu” or “Baboo” came to be a term of derision used by the British to refer to impertinent “natives” who had the temerity to imitate traits which perhaps only God and ethnology had assigned exclusively to the English gentleman.

Much of the formal correspondence between civil servants and the public during the late colonial and immediate postcolonial period in Singaporean history invariably begins as follows:

“I am directed to inform you that…”

“I am directed to acknowledge receipt of your letter of…”

“I have pleasure in sending you herewith…”

“Honoured and much respected Sir, with due respect and humble submission, I beg to bring to your kind notice”

“With regards to… I am directed to state that…”

“I beg of you to dispatch to me at your earliest convenience…”

“I hasten to beg your indulgence…”

POSTWAR SINGAPORE

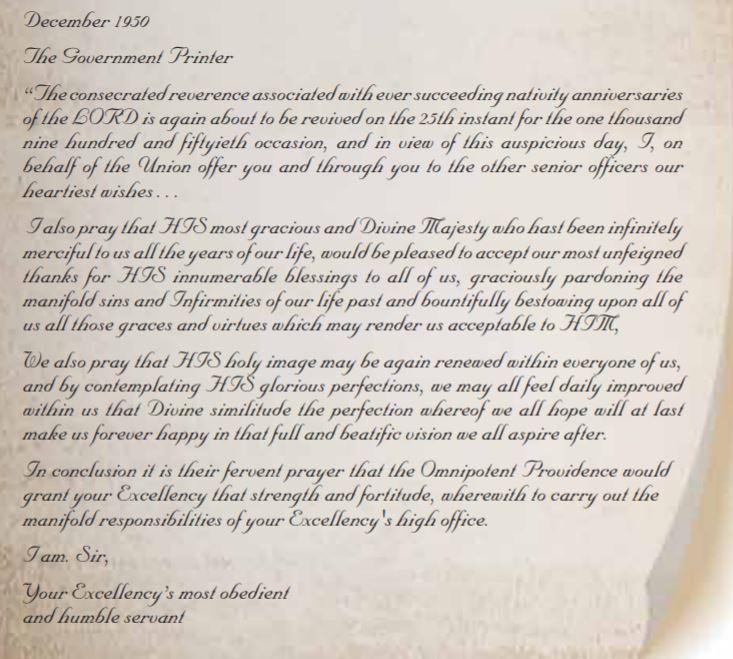

Here are two samples of correspondence that illustrate the delightful use of Babu English in colonial Singapore.

A letter addressed to the Government Printer (a British official responsible for the Government Printing Office) during the reign of King George VI, from the President of a Singapore trade union organisation. This missive was sent just before Christmas.

PRE-INDEPENDENT SINGAPORE

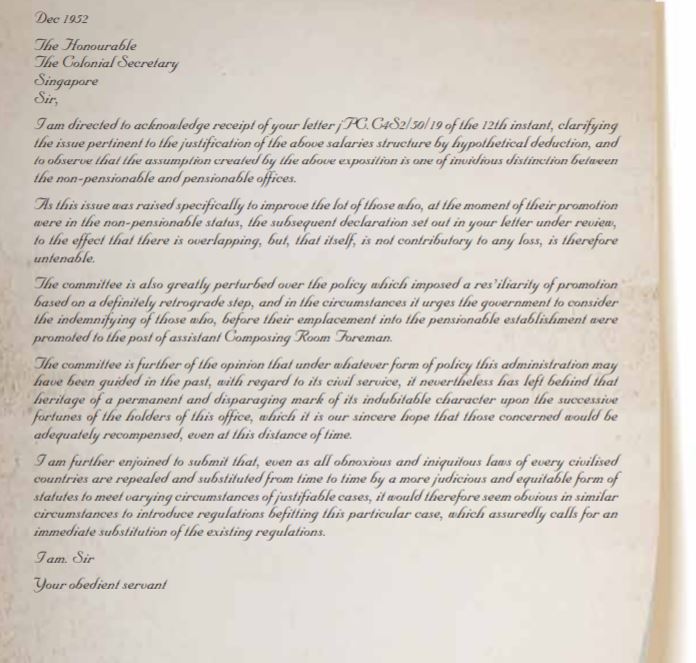

The team found many letters written in elegant English, as seen in these two examples here, while researching the files of the final years leading to independence.

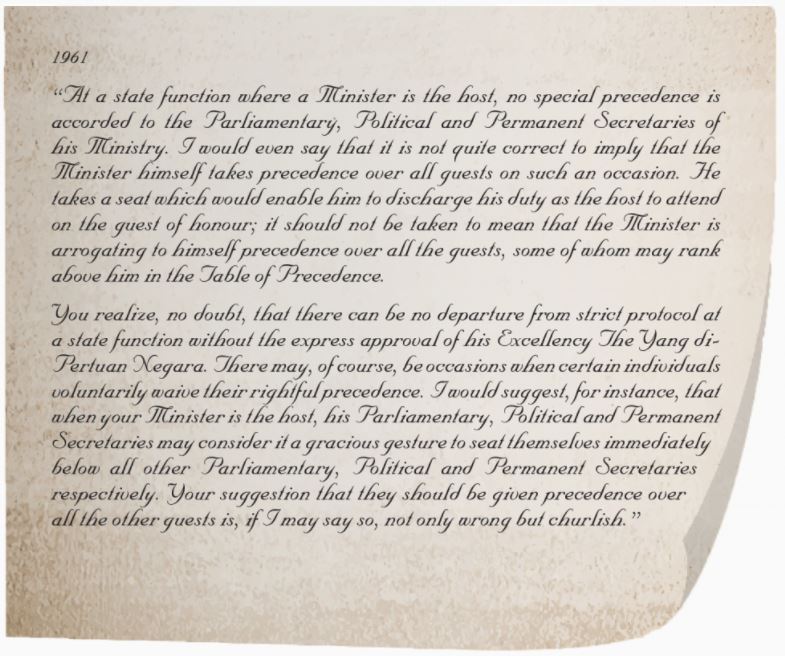

Here is a well-crafted reply from the Secretary to Prime Minister to the Permanent Secretary (Culture) on the correct protocol with regard to the seating of senior civil servants at state functions.

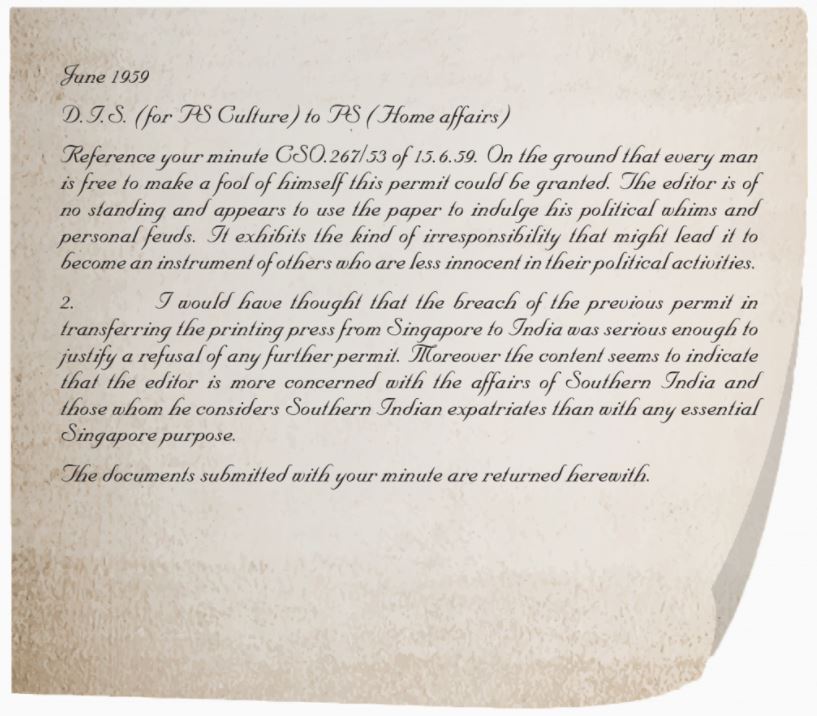

A terse letter from the Director of Information Services (Culture) to the Permanent Secretary (Home Affairs) on why a printing permit should not be granted to a certain individual.

INDEPENDENT SINGAPORE

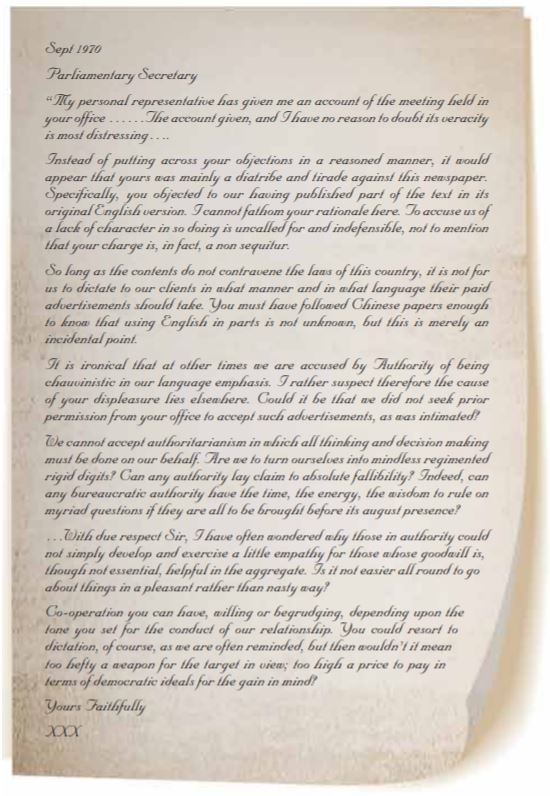

A spirited riposte from a senior staffer of a local publication to the Parliamentary Secretary (Culture). The context of this episode is perhaps better understood from subsequent developments. The publication’s top three executives were detained under the Internal Security Act in 1971 and the publication ceased operations two years later. The government statement made clear that the publication “… has made a sustained effort to instil admiration for the communist system as free from blemishes and endorsing its policies…”.3

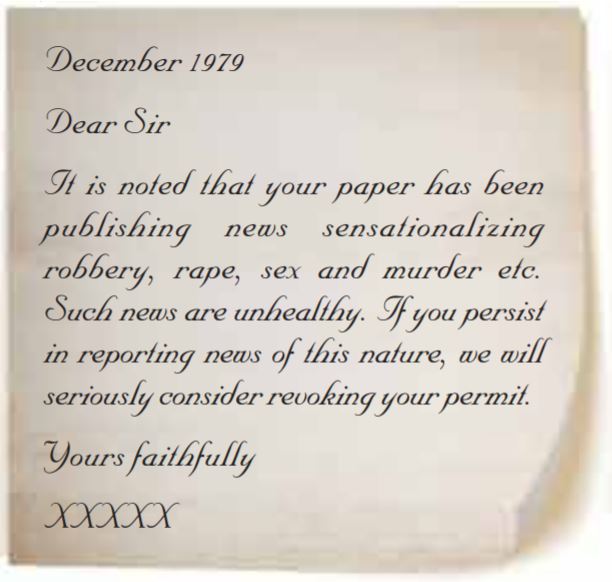

And finally, this crisp, pointed note from the Assistant Director of the Ministry of Culture to the editor of a Chinese newspaper. Never mind the flawed grammar. Its genius lies in its brevity.

The Death of Writing

To be sure, the abundance of jargon and obfuscation that can accompany the use of English in the civil service is nothing new. It is something that was first raised by Singapore’s first-generation leaders, Mr Lee Kuan Yew and Dr Goh Keng Swee in particular, in the early 1980s.

But is the problem worse today, given the pervasiveness of the internet, social media and mobile phone messaging? How has technology impacted the way we use the English language? In a world where instantaneous responses have become the norm, proper conversations and carefully thought out and crafted communications seem to have taken a back seat.

Sadly, one of the causes of the loss of clarity in writing today must surely be the demise of letter writing. As email replaces snail mail, the price of speed is the slide of composition into truncated note. In this age of ephemerality, words appear to be designed to be short-lived. And so it is – given the short screen life of electronic mail, one might well ask, where are the gems of elegant writing to be found today?

Visit the Singapore Policy History Project@ https://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/policy_history

Dr K.U. Menon is Senior Consultant at the Ministry of Communications & Information (MCI). After four decades in the Civil Service, he is currently one of the supervisors of the Singapore Policy History Project at MCI and is also as an Associate Trainer at the Civil Service College.

Dr K.U. Menon is Senior Consultant at the Ministry of Communications & Information (MCI). After four decades in the Civil Service, he is currently one of the supervisors of the Singapore Policy History Project at MCI and is also as an Associate Trainer at the Civil Service College.

NOTES

-

Ferguson, N. (2003). Empire: How Britain made the modern world. London: Allen Lane. (Call no.: RCLOS 909.0971241 FER-[USB]). ↩

-

Al-Jubouri, F.A.J. (2014). Milestones on the road to dystopia: Interpreting George Orwell’s self-division in an era of ‘Force & Fraud’. UK, Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. (Not available in NLB holdings). ↩

-

Fong, L. (1971, May 3). Three newsmen held. The Straits Times, p, 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩