Groundbreaking: The Origins of Contemporary Art in Singapore

1988 has been held as the watershed year in which Singapore’s contemporary art took root with the establishment of The Artists Village. Jeffrey Say debunks this view, asserting that the contemporary art movement began earlier.

“[T]he emergence of the Singapore artist collective The Artists Village1 arguably marks the beginning of contemporary art in Singapore.”2

This assertion by curator and art critic Iola Lenzi reflects a view that has been long accepted in writings on Singaporean contemporary art. Art curator Russell Storer, in his discussion of sculptor and painter Tan Teng-Kee’s 1979 performative work The Picnic, dismissed it as “a flash of avant-gardism within a conservative artistic environment… a form that did not take hold in Singapore for another decade until the establishment of The Artists Village in 1988”.3

Similarly, Kwok Kian Chow’s Channels and Confluences: A History of Singapore Art (1996) points to the contributions of The Artists Village and its founder Tang Da Wu to the contemporary art scene in Singapore, while generally overlooking other significant developments prior to 1988.4

In fact, the beginnings of Singapore’s contemporary art scene can be traced back at least two to three years before the formation of The Artists Village. Art historian T.K. Sabapathy has cautioned that “all too often each and every endeavour of developing new or alternative methods of making art, especially installation and performance, is invariably and unthinkingly attributed to the influence of the Village and/or Da Wu”.5

What is Contemporary Art?

Contemporary art is complex in its definition. While it is not within the scope of this essay to delve into the theoretical debates about the term, it would be useful to arrive at some definition that takes the context of Singapore art into consideration.

“Contemporary art” has been described as art produced by artists living today. Historically, contemporary art is taken to refer to new art practices such as installation, performance and video that emerged in the 1960s in Europe and America. It was a reaction against modern art, which was felt to be detached from the realities of life.

Contemporary art flourished at different times in different places in Southeast Asia. In Singapore, contemporary art is rooted in the social transformation that took place during the 1970s and 80s. As a young nation, the focus then was on generating economic wealth, along with the pursuit of rapid urbanisation and technology.

Urbanisation invariably resulted in entire communities being uprooted and relocated to high-rise housing which, in turn, led to a general weakening of societal and familial relationships. This resulted in a sense of displacement, and gave rise to issues of identity and alienation.

In the context of these conditions, young Singaporean artists responded in diverse ways to “issues relating to the nature of art, and questions regarding the self in relation to social, cultural and environmental conditions”.6 By the mid- 1980s, these artists began using a variety of new artistic techniques that were vastly different in their intent and approach compared with the abstract art forms of the preceding decades.

Precursors and Antecedents

Even before the emergence of a well-defined contemporary art scene in mid- 1980s Singapore, there have been several “flares” or “moments”, as it has been described, of contemporary art as early as the 1970s. However, it would be inaccurate to regard these instances as the budding of contemporary art in Singapore as they did not lead to the proliferation of a sustained critical practice of the form. The three early works (refer to the first text box at the end of the article) often cited as belonging to the genre of contemporary art are Cheo Chai-Hiang’s 5′ x 5′ (Singapore River) (1972), Tang Da Wu’s Earth Work (1980) and Tan Teng-Kee’s The Picnic (1979).

These works incorporate aspects of conceptual, performance and installation art, and are generally regarded as a departure from conventional painting and sculpture. In the 1980s, a number of artists – such as Teo Eng Seng and Eng Tow – began moving away from the modern towards the contemporary by creating works that can be described as bold and experimental in their use of materials and forms. Although it is difficult to establish the exact influence that such practices had on the works of young artists at the time, it would not be too far-fetched to assume that some of the momentum was carried over to the 1980s, setting the scene for contemporary art to flourish in Singapore.

The Role of Art Institutions

It would take an act of rebellion by a group of Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) students to radically shift the history of contemporary art in Singapore. Three of these students – Salleh Japar, S. Chandrasekaran and Goh Ee Choo – became pioneering figures in the contemporary art scene. Salleh recounted that the trio had, very early on, begun resisting the teaching system at NAFA, which required students to copy what they saw in a naturalistic manner and to follow the tradition of the Nanyang School. Finding the teaching dull and unimaginative, the students went on to build a more experimental portfolio in parallel to their mandatory school portfolio.7

As a further gesture of dissent, the three young rebels, together with two other students, Koh Kim Seng and Desmond Tan, decided not to participate in their graduation show. Instead, the five staged their own “graduation” show – Quintet – at Arbour Fine Art in May 1987.

The founding of LASALLE College of the Arts, then known as St Patrick’s Arts Centre, by Brother Joseph McNally in 1984 was a catalyst in the growth and development of Singapore’s contemporary art scene (LASALLE has since acquired a reputation for its contemporary arts education, while NAFA is better known for its more traditional approach in the training of artists).

According to an interview with former LASALLE student Ahmad Abu Bakar (Diploma of Fine Arts, class of 1989), now a ceramicist and sculptor, the school focused more on conceptual thinking rather than artistic skills during its early years.8 The highly influential artist Tang Da Wu, who began teaching at LASALLE in 1988, encouraged students to think out of the box and invited them to his performances and events.9 LASALLE students also became involved in a number of external contemporary art events and activities during this period.10 Interestingly, much of the study of contemporary art practices were taking place outside the classroom.

Before the establishment of the Singapore Art Museum in 1996, the National Museum Art Gallery was the state museum where art exhibitions were held. The role played by this art gallery, which opened in 1976, in the development of contemporary art in Singapore cannot be understated. Although the gallery did not provide a platform for young local artists, the numerous shows it staged that featured the works of well-known international artists would have inspired students from LASALLE and NAFA.11 It is highly plausible that exposure to these international shows would have had an impact on more intrepid art students as well as emerging artists, many of whom could have been influenced by the experimental works on display.

Foreign cultural institutes in Singapore, such as Alliance Francaise, The British Council, the Australian High Commission (which organised the Australian Art Award for Young Artists)12 and the Goethe-Institut, also served as platforms for learning and exhibitions. The Goethe-Institut was especially instrumental in providing an alternative space for the display of contemporary art: its exhibitions of works by German artists and film screenings would undoubtedly have been seen by young local artists and, in turn, energised their own practice. In addition to hosting the graduation shows of NAFA and those of young emerging artists,13 the Goethe also had a library that was well stocked with art books – a useful resource for young artists looking for ideas from outside Singapore.

Groundbreaking Art

Interestingly, many of the visual art exhibitions that featured cutting-edge works by young and emerging artists during this period were organised as part of the Fringe segment of the Singapore Festival of Arts. The Fringe showcased events featuring visual and performing arts that frequently crossed from one discipline to the other. The Fringe was exactly what the term stood for – non-mainstream events that encouraged greater experimentation and diversity of visual expressions, which in turn expanded the scope of contemporary art practice in Singapore.

In the 1986 edition of the Fringe, the works of 12 young artists were shown in five venues14 here. One of the shows, Not the Singapore River, held at the now defunct Arbour Fine Art in Cuppage Terrace, would become part of local art history. Although short-lived, Arbour Fine Art and its co-owner, Lim Jen Howe, played an instrumental role in providing a platform for untested young artists brimming with fresh ideas to exhibit their works.

By naming the exhibition Not the Singapore River, Lim had intended to usher in a new era in the local art scene, representing a break from the so-called second-generation artists who were either painting abstractions, or clichéd and idyllic scenes of the Singapore River and Chinatown. The five artists featured in Not the Singapore River were Goh Ee Choo, Oh Chai Hoo, Katherine Ho, Yeo Siak Goon and Peter Tow. Although the works exhibited were primarily paintings, their experimental interplay of form and space, and the use of motifs and symbols as metaphors for self-reflexivity leaned towards contemporary art.

The aforementioned Quintet exhibition by NAFA’s five young artists, held at Arbour Fine Art in May 1987, was arguably the most significant art exhibition in the second half of the 1980s, and its radical origins have been noted by various writers. The reviewers of the show were quick to point out the innovative components of Quintet,15 here with its works displayed on the wall, floor and ceiling in seemingly random fashion.

While the art works of Desmond Tan and Koh Kim Seng of Quintet conformed to the conventions of easel paintings, those of Salleh Japar, Goh Ee Choo and S. Chandrasekaran broke new ground in Singaporean art. Drawing from Asian heritage and philosophy, their works were a direct reaction to Western-centric art practices prevailing in Singapore. The use of objects such as sand, stones, dried leaves, barbed wire and even a kitchen wok, arranged as installations on the floor or as constructions on the wall – and the creation of a total and immersive art environment in the process – were the key elements that made it so revolutionary.

Significantly, too, Quintet was the precursor of the well-documented Trimurti that was staged in 1988 – the same year The Artists Village was launched. Trimurti is regarded today as a seminal exhibition in the history of Singaporean contemporary art (see second text box at the end of the article).

In 1988, an unsung figure in Singaporean contemporary art history, the French-born multidisciplinary artist Gilles Massot, conceived and organised Art Commandos, a group of about 30 individuals who launched “raids” into the city area as part of the 1988 Arts Festival Fringe. The “raids” constituted one of the first instances of intervention by a group of creative individuals in a public space.

After having trained for a week under different mentors in an experimental workshop in Sentosa that combined visual art, music, drama and dance, the Art Commandos settled into their “base camp” at the former St Joseph’s Institution (now Singapore Art Museum), from where they fanned out into various parts of the city, including Orchard Road. The performances were spontaneous and involved members of the group expressing themselves in song, dance and drama, and using a variety of artistic props made from readily available materials.

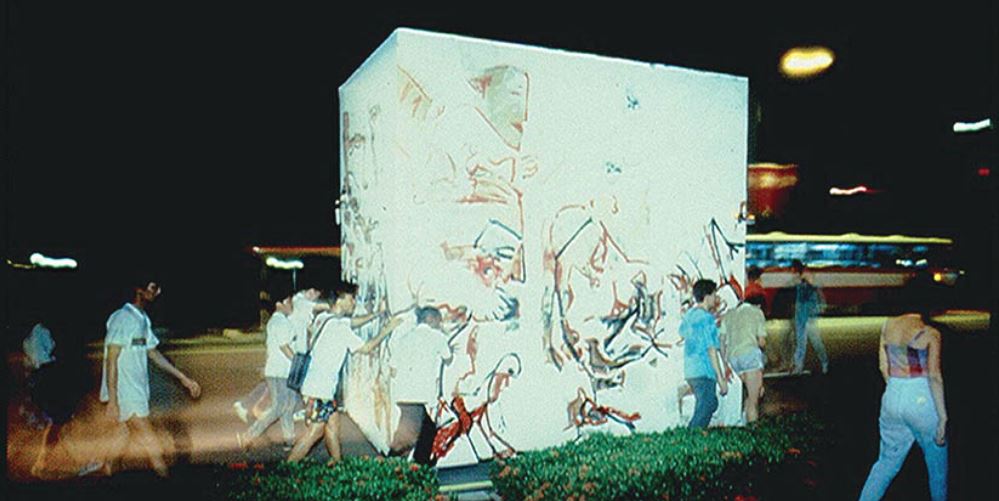

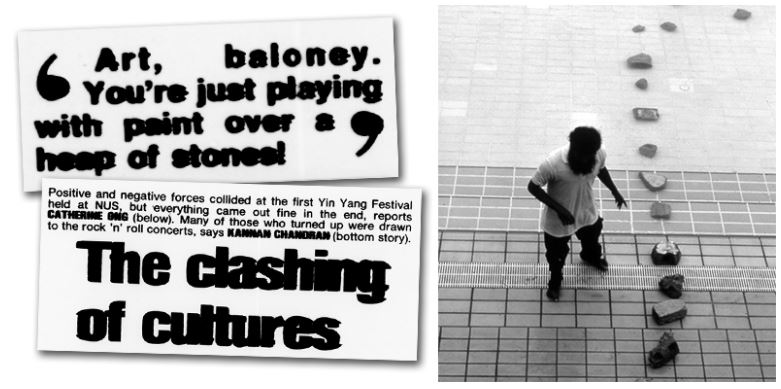

Massot had earlier co-curated a six day interdisciplinary event from 19 to 24 November 1987 called the Yin Yang Festival, organised by the National University of Singapore Society. It included an outdoor performance by S. Chandrasekaran, which saw the artist leading a procession of chanting performers carrying stones while clashing cymbals resonated in the background. They then proceeded to arrange the stones in a mound while throwing “bits of plastic, sponge and paint over them in a random fashion”.16

Another innovative event that was part of the 1988 Fringe took place on the premises of the former St Joseph’s Institution in June. It was one of the first instances where a group of artists took over a vacated building and transformed it into a dynamic art space with site-specific works that involved active audience engagement. Titled More Than 4, it was staged by four young artists – Tang Mun Kit, Baet Yeok Kuan, Lim Poh Teck and Chng Chin Kang.

Occupying old classrooms, corridors and other spaces, the artists responded to the building’s former life as a school by using materials and furniture salvaged from the premises in their installations. Experimental works were placed alongside school remnants such as blackboards, desks and notice boards. The artists also made personal interventions in public spaces; in one instance, a girl wrapped in white and strapped to the front of a wooden box was pushed from the school to Marina Square. Outside Raffles City, a shirtless Tang Da Wu “ran up to the girl at top speed and screamed into her face…” He then grabbed the girl and said: ‘This is live art’”.17

In September 1988, Cheo Chai-Hiang presented an installation titled Gentleman in Suit and Tie. Artist and archivist Koh Nguang How recalls how, at the opening event, 60 audience members, each equipped with a charcoal stick and a piece of paper pre-printed with a man’s image, simultaneously started running their charcoal sticks over the image – in effect producing 60 portraits in one fell swoop – as guest-of-honour and then principal of LASALLE College Brother Joseph McNally walked the length of the gallery while a flautist played in the background.

Cheo’s work can be framed within what is known as relational aesthetics, in which the artist is viewed as merely a facilitator and art is regarded as the exchange of information between the artist and the audience.18 “The artist, in this sense, gives audiences access to power and the means to change the world”.19 It is clear that Cheo was years ahead of his time.

Public Reception and Perception

The public reception to contemporary art in Singapore has been mostly overlooked in existing writings. One of the strongest indicators that a contemporary art scene had emerged in the mid-1980s was the public discourse that took place in response to its development. By its very nature, contemporary art is meant to be provocative and interactive, demanding, as it were, the audience to participate. The coverage of the visual arts in the press and other writings during this period were largely attempts to make sense of some of the avant-garde and experimental art practices that had begun surfacing. The cutting-edge quality of contemporary art inevitably elicited strong reactions from the public.

During S. Chandrasekaran’s performance for the Yin Yang Festival in November 1987, for instance, players at a nearby tennis court got into a heated exchange with members of the artist’s procession, questioning whether splashing paint over a heap of stones can be considered art.20 In July 1988, a member of the public wrote to The Straits Times, expressing disappointment with the Art Commandos, criticising the artistic quality of the performers and the lack of good content.21

Much of the criticisms, particularly in newspapers and magazines, took aim at the seemingly gimmicky and experimental nature of the works, which themselves were a barometer of a growing interest in forms and practices that were shifting from the more familiar art of the 1970s and early ’80s that were expressed mainly through paintings, sculptures and salon photography. The reactions from both audience and journalists ranged from utter bewilderment to complete denial that what they were witnessing was art. But ironically, headlines such as “Art or gimmick?”.22 and “A year when the young hogged the limelight”23 were ample evidence that new art forms were emerging in Singapore.

Among those who contributed art reviews and columns to The Straits Times was the prolific art historian T.K. Sabapathy, whose incisive remarks and critical tenor were hallmarks of his writing. Sabapathy’s reviews were a reflection of the personal relationships that he had forged with many contemporary artists during their formative years.

It is clear that the growth of Singapore’s contemporary art scene cannot be single-handedly attributed to the establishment of The Artists Village in 1988. There is sufficient evidence that contemporary art was already beginning to take root in the early 1980s and made especially significant inroads between 1986 and 1988 when young artists, disillusioned with outmoded ways of making, displaying and viewing art, began experimenting with new techniques and forms that would in time be regarded as contemporary art.

A confluence of various factors – institutional support and reception by the media, innovative individuals and groups, and cutting-edge exhibitions – were responsible for the development of contemporary art in Singapore during this period. This would provide the momentum needed to carry contemporary art forward to the 1990s and beyond.

THREE ARTWORKS AHEAD OF THEIR TIME

In 1972, Cheo Chai-Hiang submitted a proposal, titled 5′ x 5′ (Singapore River), to the annual exhibition of the Modern Art Society. The proposal contained a set of instructions directing the exhibitors to draw a square measuring five feet by five feet straddling the wall and the floor. Cheo’s work was an example of conceptual art, in which the idea or the concept was more important than the actual execution or aesthetics. At one level, the work was a parody of the cliched representations of the Singapore River popular among painters then. On another level, it was a critical work meant to provoke discourse about the general state of art in Singapore, which had hitherto been dominated by international abstraction. Given its iconoclastic nature, 5′ x 5′ (Singapore River) was not selected for the 1972 Modern Art Society exhibition.

Even before Tang Da Wu returned from undergraduate studies in the UK in 1979, he had begun engaging in experimental art forms such as performance and installation. In 1980, Tang presented an exhibition titled Earth Work at the National Museum Art Gallery. Earth Work featured lumps of earth, soil and clay as well as linens and wooden boards that had been exposed to the sun, rain and soil. One of these works, Gully Curtain (1979), was created on-site by hanging seven pieces of linen in a gully in Ang Mo Kio, which was then being developed into a public housing estate. Left in the gully for three months, the resulting soiled and water-stained linens became part of his exhibition at the gallery.

Tan Teng-Kee staged The Picnic as an outdoor event at the field outside his flat in Normanton Estate on 14 September 1979. While there was nothing extraordinary about the exhibition of several of Tan’s paintings and sculpture, what was highly unusual was the inclusion of a series of actions that is today regarded as the first documented instance of performance art in Singapore. One of the works featured was a 100-metre-long painting, The Lonely Road, which Tan sliced into smaller paintings in response to what potential buyers wanted. The climax of the event was Fire Sculpture, which saw one of Tan’s constructions – wrapped in newspaper and supported by long wooden poles – incinerated with a torch. The Picnic, however, was an isolated occurrence in Tan’s practice, which was primarily sculpting.

TRIMURTI: A RETURN TO ASIAN AESTHETICS

In March 1988, Goh Ee Choo, Salleh Japar and S. Chandrasekaran staged an exhibition at the Goethe-Institut titled Trimurti. The exhibition was, in many ways, a crystallisation of the ideas and concepts that they had been working on in Quintet that took place in May 1987. In Quintet, these three artists drew extensively from Asian philosophical systems relating to ideas of creation and the cosmos, but with Trimurti, these ideas became more fully fledged and explicit as concepts underpinning the exhibition.

Trimurti is a Sanskrit word that describes the Hindu triumvirate of Shiva (the Destroyer), Vishnu (the Preserver) and Brahma (the Creator). These roles were symbolically appropriated and executed by Chandrasekaran, Goh and Salleh respectively in the exhibition. Trimurti was an assertion of the ethnic and cultural identities of the three artists (Indian, Chinese and Malay), combined into a syncretic unity – an acknowledgement of Singapore’s multiethnic and multicultural society. Unlike Quintet, Trimurti had all three artists engaged in ritual-like performances, in addition to installations as well as painted and sculptural works that are charged with symbolism – all geared towards transforming the gallery into what the artists called an “energy space”.

After this event, Goh, Salleh and Chandrasekaran never exhibited collectively again, but went on to forge successful individual careers as artists. The only exception was in 1998, when the artists reprised Trimurti in the exhibition Trimurti and Ten Years After at the Singapore Art Museum.

The author hopes this essay will lead to further discourse on the individuals, exhibitions and institutions that have contributed to the growth of the contemporary art scene in Singapore. As part of his research, he interviewed three individuals who have been instrumental in this area: artist and photography historian Gilles Massot; artist and archivist Koh Nguang How; and ceramicist and sculptor Ahmad Abu Bakar. The author would also like to thank Salleh Japar and Goh Ee Choo for allowing access to their archival materials, and to Seng Yu Jin and S. Chandrasekaran for sharing their knowledge.

Jeffrey Say is an an art historian and lecturer at LASALLE College of the Arts, where he helped develop its art history programmes. He undertook the first extensive study of the history of sculpture in pre- and post-war Singapore, and is co-editor of Histories, Practices, Interventions: A Reader in Singapore Contemporary Art (2016).

Jeffrey Say is an an art historian and lecturer at LASALLE College of the Arts, where he helped develop its art history programmes. He undertook the first extensive study of the history of sculpture in pre- and post-war Singapore, and is co-editor of Histories, Practices, Interventions: A Reader in Singapore Contemporary Art (2016).

NOTES

-

The Artists Village (TAV) is an artist colony founded by artist Tang Da Wu in 1988 at Lorong Gambas in Sembawang. Tang invited young artists such as Wong Shih Yaw, Lee Wen, Amanda Heng and Zai Kuning to set up their studios in a kampong setting there. In the following year, TAV became active with open studio shows, installations and performances, held at Lorong Gambas and venues such as the National Museum Art Gallery. In 1990, Lorong Gambas was repossessed by the government for redevelopment and TAV moved to a number of different temporary locations. ↩

-

Lenzi, I. (c. 2009). The Artists Village and the birth of contemporary art in Singapore: Koh Nguang How in conversation with Iola Lenzi. In I. Lenzi (Ed), Concept, context, contestation: art and the collective in Southeast Asia (pp. 190–195). Bangkok: Bangkok Art and Cultural Centre Foundation. (Not available in NLB holdings). ↩

-

Storer, R. (2016). Melting into air: Tan Teng-Kee in Singapore. In R. Storer, C. Chikiamco & A. Tan (Eds.), A fact has no appearance: Art beyond the object (pp. 55–67). Singapore, National Gallery, Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 709.5909047 FAC). ↩

-

Kwok, K. C. (1996). Channels and confluences: A history of Singapore art. Singapore, Singapore Art Museum. (Call no.: RSING 709.5957 KWO). ↩

-

Sabapathy, T.K. (1993, June). Trimurti: Contemporary art in Singapore. Art and Asia Pacific, pp. 30–35. (Not available in NLB holdings). ↩

-

Sabapathy, Jun 1993, pp. 30–35. ↩

-

Sheares, C. (Interviewer). (1998, April 15). Oral history interview with Salleh Japar [Transcript of recording no. 002018/4/1, p. 2]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. Art history has shown that new movements – from the Impressionists to the Vienna Secessionists – invariably started when students and young artists rebelled against prevailing art practices that they deemed to be conservative, constraining and outmoded. ↩

-

Interview with Ahmad Abu Bakar, 16 February 2019. ↩

-

Interview with Ahmad Abu Bakar, 16 February 2019. ↩

-

These included Art Commandos, Yin Yang Festival and Cheo Chai-Hiang’s Gentleman in Tie and Suit. ↩

-

Interview with artist and archivist Koh Nguang How, 13 February 2019. In 1978, the National Museum Art Gallery held an exhibition of noted American artist Helen Frankenthaler. In 1987, it co-organised a show by prominent contemporary Chinese painter Liu Haisu and also showcased a contemporary German kinetic art exhibition in the same year. In 1978, it held an exhibition of German expressionist prints. ↩

-

A biennial art competition organised by The Singapore Business Art Council in association with the Australian High Commission. The top prize was a 12-week scholarship to study at the City Art Institute in Sydney and at the Canberra School of Art. ↩

-

Interview with Koh Nguang How, 13 February 2019. Ms Moh Siew Lan, a cultural officer at Goethe-Institut, approached Goh Eee Choo, Salleh Japar and S. Chandrasekaran – course mates at NAFA – to hold a group show at Goethe as a follow-up to Quintet. This resulted in the seminal exhibition Trimurti. ↩

-

Arbour Fine Art, Gallery Fine Art, Art Forum, Chesham Fine Art and Saxophone Bar and Restaurant. ↩

-

Sabapathy, T.K. (1987, May 14). Art on the ceiling, walls and floor. The Straits Times, p. 25. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Chua, B.H. (1987, Aug/Sept). Young artists make a break: Installation at Arbour. Man, 18–20. ↩

-

The Yin Yang Festival included art and photography exhibitions, dance and music performances, talks, an art camp, video shows, and installation works. See Ong, C. (1987, November 24). The clashing of cultures. The Straits Times, p. 25. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wong, M. (1988, 20 June). Art or gimmick. The Straits Times, p. 29. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Relational aesthetics was coined by the French curator and art critic Nicholas Bourriaud in the 1990s to describe art based on human relations and their social contexts. ↩

-

Tate. Art term: Relational aesthetics. Retrieved from Tate website. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 24 Nov 1987, p. 25. ↩

-

Commandos: Antics or art. (1988, July 1). The Straits Times, p. 31. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 20 Jun 1988, p. 29. ↩

-

A year when the young hogged the limelight. (1987, December 27). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩