Georgette Chen: Artist Extraordinaire

Sara Siew examines the link between visual art and the written word through the fascinating story of Singaporean artist Georgette Chen.

Artists express themselves in a variety of ways. Although art is the most obvious of these, some artists also rely on the medium of words as a means of self-expression. From private musings and working notes to published essays and interviews, many artists have chronicled their experiences, thoughts and feelings through the written and spoken word.

Some writings, like manifestos and declarations, tell us about the ideas behind a certain style or about the context in which artists worked, while others strike a deeper, more emotive chord. The Dutch post-impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh, for example, wrote 800 or so letters to his younger brother Theo, laying bare his private anguish and joys, and in the process painted a portrait of himself that is arguably as compelling as his artworks.

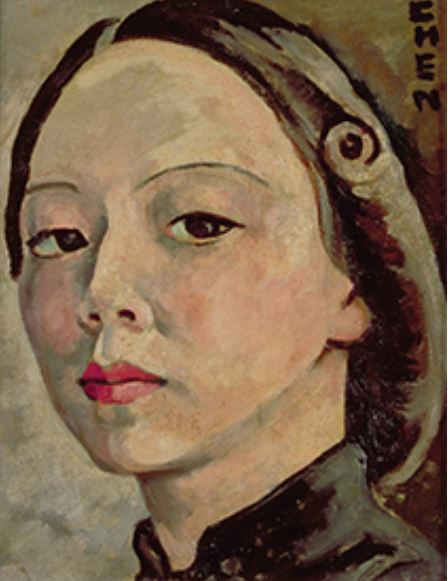

The celebrated Singaporean artist Georgette Chen (1906–93) also wrote extensively. Chen’s achievements as an artist are widely recognised: her lively oil paintings of the places and people of Singapore at a formative time in its history have cemented her status as one of the nation’s most important first-generation artists; she was also a respected art educator for 27 years and a Cultural Medallion recipient. Less well known, however, is her personal story, one that spans wars and revolutions, triumph and tragedy, and loves lost and found.

A Life Less Ordinary

“I often sit quietly in the silence of the night and wonder at the mysterious drama that is life…”1

Georgette Chen, who was named Zhang Liying when she was born in October 1906, was the fourth daughter of Zhang Jingjiang, a wealthy Chinese merchant. Growing up, Chen experienced a cosmopolitan and privileged upbringing in Paris, New York and Shanghai.

Chen’s father had encouraged her interest in art since young, even engaging a private art tutor, Victor Podgorsky, for her. Father and daughter, in fact, attended these lessons together. Chen’s affinity for oil as a medium was apparent even then.

She recalled of her childhood: “My father expected me to study Chinese painting, but I had a different idea. I told him I wanted to study the oil medium, which would enable me to paint everything around me, people, food, flowers, salted ducks, sampans, peasants and potatoes.”2 On another occasion, she remembered her father “impatiently enumerat[ing] the long list of Chinese vegetables which could be painted. He wanted to know why I insisted on painting the foreign potato”.3

Chen’s foundation in oil painting was further developed when she studied art in New York (1926–27) and then Paris (1927–33). Her time in the French capital was perhaps the most significant. The City of Light was not unfamiliar to Chen; having spent part of her childhood there, she spoke fluent French and was well acquainted with the sights and sounds of Paris. Chen counted the Tuileries Garden and Parc Monceau among her favourite childhood haunts and, decades later, would still delightfully recall riding on the merry-go-round at the park and feeding her favourite swans at the Tuileries.

Revisiting Paris in her early 20s, now as a budding artist, further strengthened Chen’s relationship with the city. While enrolled at the less structured art schools of the Académie Biloul and Académie Colarossi, Chen also carved for herself an education that extended far beyond the classroom. She travelled around Paris frequently, seeking subjects to paint and relishing “the freedom of painting whatever you like”.4

Chen gradually found acclaim, beginning with the acceptance of one of her paintings by the Salon d’Automne in 1930, an annual exhibition that had by then transcended its beginnings as an alternative to the official conservative salon to become an influential, progressive platform in the Parisian art world. She also started to exhibit regularly in other salons and participated in two major exhibitions in 1937: Palace of Painting and Sculpture as part of the Paris World Fair, and Les Femmes Artistes d’Europe Exposent (Women Artists in Europe) at the Jeu de Paume museum.

Beginnings and Endings

“A good love story is always close to one’s heart.”5

Paris augured exciting beginnings for Chen not just in art, but also in her personal life: it was here where she found a love that was to become her most enduring. In 1927, at the age of 21, she met Eugene Chen in Paris. The two were introduced by their mutual friend Soong Ching Ling, more famously known as Madam Sun Yat Sen (Chen’s father was a key funder of Sun Yat Sen’s political activities in China).

Eugene, a political journalist and respected diplomat, had been Sun’s foreign policy adviser from 1922 to 1924 and, following that, the minister for foreign affairs of the nationalist government in Wuhan, China. With the collapse of the nationalist government in 1927, Eugene found himself exiled in Europe, his political career in limbo. His encounter with Georgette Chen was, however, to bloom.

Despite their vastly different professions, the two were aligned in their mutual love for the arts. Chen recalled: “Well, in the first place he always loved art, music, literature, French. He was a very good French scholar as well. And he was always ready to pose for me. That always helps an artist. He always told me not to sew because there were many tailors who could do the work. And if I wanted to sew, then it was better to take up my easel and paint instead”.6

Despite their 30-year age difference, and the initial disapproval of Chen’s father at their pairing, the couple found in each other “the closest of companions”,7 and were married in Paris in 1930. Chen would take on Eugene’s surname and retain it even when she remarried after his death.

The revelatory nature of the written word – even of life at its most mundane – is exemplified in Chen’s writings. The simple, sequestered joys that she shared with Eugene in Paris were rarely mentioned publicly; rather, they were expressed in diaries where she recorded the minutiae of everyday life with her husband – from giving him a haircut to talking a walk together to search for pineapples and avocados for a still-life painting. In one candid entry, she wrote: “Begin small canvas of E portrait. Poses so badly & talks all the time.”8

Chen recorded not just details of her daily life but also, significantly, information on her art and the subjects she was studying or portraying, with descriptions such as “roses still-life 10F” and “nature morte 6F”, terms that likely refer to standard French canvas sizes. On occasion, she would also briefly mention if her painting or study was successful, or if it had to be executed again. These details, which Chen recorded dispassionately and faithfully, offer precious insights into the often hidden and banal aspects of artistic practice, as well as the hard work and dedication behind an artist’s craft.

Over time, Chen’s writings also bear silent witness to the progression of her career: while early diary entries speak of these attempts and studies, later accounts (which appeared in letters to family and friends instead) describe the pieces she was commissioned to create, her attempts at juggling painting and teaching, and the tedium of preparing for exhibitions or judging on committees.

Chen’s blissful life in Paris as a happy newlywed and an emerging artist was soon compromised by the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937. In 1941, while she and Eugene were living in Hong Kong, they were detained by the Japanese and placed under house arrest before being moved to Shanghai, where they were interned until 1944.

During their time in the Chinese city, Eugene was often called up for “interviews” with the Japanese; fearing for Chen’s safety, he always insisted on taking her everywhere he went.9 Chen would later recount an exchange between Eugene and a Japanese officer at one of these sessions, following yet another failure on the part of the Japanese to secure her husband’s cooperation:

“Another arrogant Japanese left our sitting room humble and human again. These were his parting words: ‘Other Chinese leaders have several faces and several tongues, but you, Mr Chen, have only one face and one tongue…’ And in his characteristic humour, Eugene replied: ‘That is precisely why I must not be made to lose that one and only face and tongue, having no spares’.”10

Eugene Chen passed away in 1944 at the age of 66 due to ill health. He was still under house arrest in Shanghai at the time.

Peace in a New Land

“We have all found peace of mind in a land which is not our own…”11

When Chen wrote these words in a letter to Dorothy Lee, Eugene’s cousin, in 1961, she was 55 years old and living alone in Singapore. Much had transpired in the 17 years since her husband’s death, bringing her serendipitously to a Southeast Asian island that was worlds away from the cities she had known: Paris, Shanghai and New York.

Following the end of World War II, Chen stayed in China until 1947, when she left for New York. That same year, she married Dr Ho Yung Chi, Eugene Chen’s colleague and an old mutual friend of theirs. Together, Chen and Ho lived in New York then Paris, all the while bearing hopes of eventually returning to China. However, in the absence of better prospects in China, the couple eventually decided to take up an offer to teach at Han Chiang High School in Penang, Malaya, arriving in 1951 to what Chen described as “a beautiful tropical island which I call my Tahiti”.12

While Chen was immediately enthralled by this new land and enjoyed her life in Penang immensely, the experience was marred by growing strife in her marriage. Her relationship with Ho was increasingly plagued by bitter arguments over issues like money (she suspected Ho to have an ulterior motive) and her continued use of Eugene’s surname. Chen’s eventual decision to part with Ho was further complicated by intransigence on his part, and it was only after a lengthy, draining process that the couple were eventually divorced in 1953, after six years of marriage. In the same year, Chen moved to Singapore.

Chen arrived in Singapore with renewed hope for a peaceful life. In a letter to friends in early 1954, she said: “With my regained liberty, I now look forward to a simple, useful, and creative existence for the remaining short years that are left.”13 She rented a house in Sennett Estate and took up part-time teaching at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, a move that would allow her to pursue her art independently while supporting herself financially.

She frequently described this arrangement in her letters as allowing her to have “bread without butter”, and with characteristic good humour, often added, “I don’t like butter much anyway, too fattening!”14 Despite the toll of age and debilitating rheumatoid arthritis (a condition that began in her 40s), Chen adopted a simpler lifestyle – one far removed from the material comforts of yesteryear – with bravado, relishing even “the ordinary chores of life”.15

Paradise on Earth

“So you can see why I am fast becoming a tropical plant and desire nothing more than to spend the rest of life painting the vivid motifs of this multi-racial paradise of perpetual sunshine.”16

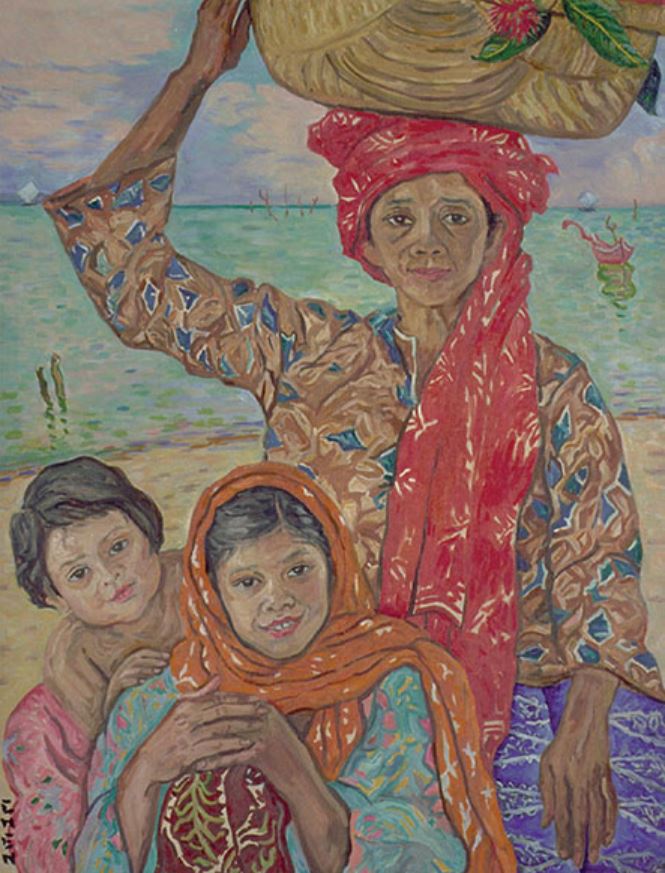

The simple, satisfied existence in Malaya that Chen often spoke of was due to her art, which flourished in this land she now called home. From the 1950s to the 70s, she firmly established herself artistically, creating many of the paintings she is known for today. This would, arguably, not have been possible if she had not settled down in Malaya: so closely intertwined was her art with its people and places.

Chen, in turn, would increasingly identify herself as being a part of this land, a new citizen who set out to learn the mother tongue Malay, print her own batik and adopt the Malay nom de plume of Chendana (which refers to fragrant sandalwood), becoming, in a sense, the metaphorical tropical plant she often wrote about in her letters. Her art and life were an indivisible whole that was inextricably linked to the land she had settled into.

Chen’s enchantment with Malaya was, in fact, already apparent when she first arrived in Penang in 1951 with Ho. In a letter written a few months after her arrival, she had gushed about her new home:

“I have always had a sort of weakness for this little island while passing through it on my many journeys westward and hoped that some day, I may have more than just a glance at it. It is called the ‘pearl of the East’ or ‘Paradise on Earth’ not without reason. If Malaya does not prove to be a fruitful period for me artistically, it shall not be for the lack of beauty which seems to be everywhere… The waterfront with the rows of Malayan straw huts bathing right in the water whose color is green and violet, make me shout with excitement each time I pass them by… As to the great variety of fruits, with their strange, new, and unexpected forms, they are not only wonderful to look at but delicious to eat! I have been introduced to the Durian fruit and consider that my life has been enriched by it!”17

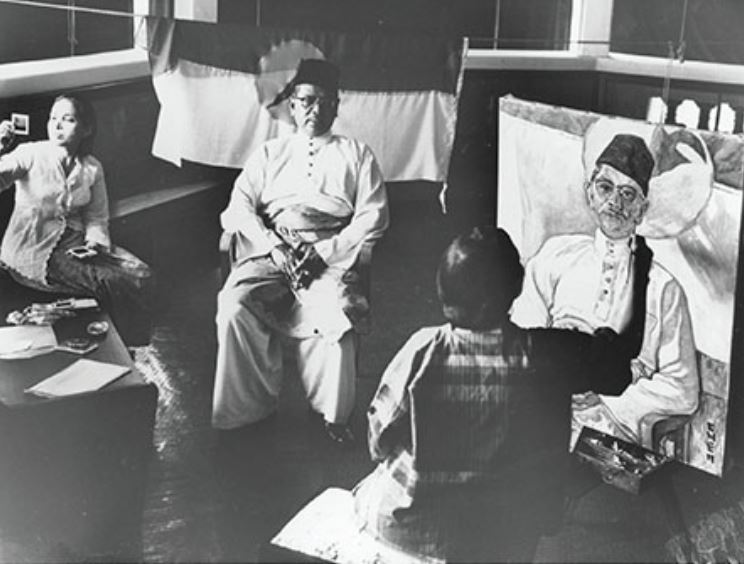

The inspirations and attractions that Malaya afforded clearly invigorated Chen. She made no secret of the “inexhaustible motifs”18 that she found in this “seasonless newfoundland”,19 which she embraced wholeheartedly. Tropical fruits in their bright colours and variegated forms take centre stage in her still life paintings. These are accompanied by depictions of daily scenes: from a bustling outdoor market to a satay seller working by the beach, to the Singapore River. Chen’s portraits, which she was frequently commissioned to make, form another compelling body of work; whether they portray her family and friends (including the first prime minister of Malaysia, Tunku Abdul Rahman) or strangers, these depictions are warm and intimate, sometimes capturing their subjects in the middle of private, interior moments.

Chen often professed, in letters to friends, of her desire to spend the rest of her life depicting Malaya and its motifs. This desire was, however, stymied by age and debilitating illness. She battled rheumatoid arthritis from her 40s until death. The condition, which had also afflicted her father, caused much pain and lack of mobility (in one account, a severe attack in her knees left her “hobbling on a stick for months and months”20), which, although controlled by medication, worsened over the years. This was in part and, quite ironically, due to the medicine that Chen was taking religiously, a side effect of which was osteoporosis.

Despite having to deal with the painful condition alone, Chen remained strong and gentle in spirit; it is in this regard, perhaps, that her writing is most instructive, for it reveals her character in a way that her paintings arguably could not. In letters to friends, Chen often spoke about how “life is anguish and blessings all intermingled which we must accept and carry on as best we can”.21 True to this proclamation, she seemed to accept her adversities stoically, however big or small, and forge ahead. The measure of Chen’s inner strength further comes through in the self-deprecating humour evident in her writing. In a letter to Patricia Kennison, one of her students who later became a close friend, she compared herself to an old, worn machine:

“My ‘full form’ can partly be explained by the fact that friends always revive me, for there are times when I do feel quite PATRAQUE, to use an apt French word. (patraque: both a’s are short. Said of a machine that functions badly because it is badly made or old.) But on the whole the slow coach has gone fairly well after its last major repair though the rounds have not been reduced.”22

As Chen alluded to in her letter, it was the simple joy of friendship – in addition to art and a home she loved – that helped sustain her through adversity.

The Last Chapter

In an introspective moment while writing to Eugene’s cousin Dorothy Lee in 1967, Chen, then 61, offered what could be described as a summary of her remarkable life:

“I shall be glad to leave my pictures to Singapore and Malaysia as my little contribution to this tropical land in which I have found rehabilitation. This last chapter of mine on this ‘treasure island’ which I call my ‘Tahiti’ (Tahiti, as you know, is another tropical island where the French painter Gauguin adopted as his new home) has been creative and peaceful. Here, I have stood on my own two feet, albeit arthritic, and I have cut a happy coat with his colorful tropical cloth at my disposal. I have tried to pursue my work to the best of my ability, I have continued to be myself seeking neither fame nor riches. Art like love and friendship or religion is a pursuit of love and devotion. I have respected and cherished my friends and have tried hard not to take advantage of them and their love has kept me alive. Sometimes when I think that I am the product of four world events, all wars – two Chinese revolutions, the one of Dr Sun and Mao Tse-tung and the 1st and second World Wars in all of which I have been inexorably involved, the wonder is that my profession should have been one of good-will and peace! Only God can answer for these paradoxes…”23

In 1981, Chen suffered a serious fall. She was hospitalised and required hospice care for the next 12 years until her passing in March 1993 at age 87. Following Chen’s death, 53 of her paintings as well as a voluminous archive of her personal papers and belongings were bequeathed to Singapore. Georgette Chen’s love for and gratitude to this land – “this tropical land in which I have found rehabilitation” – had finally come full circle.24

SPEAKING OF…

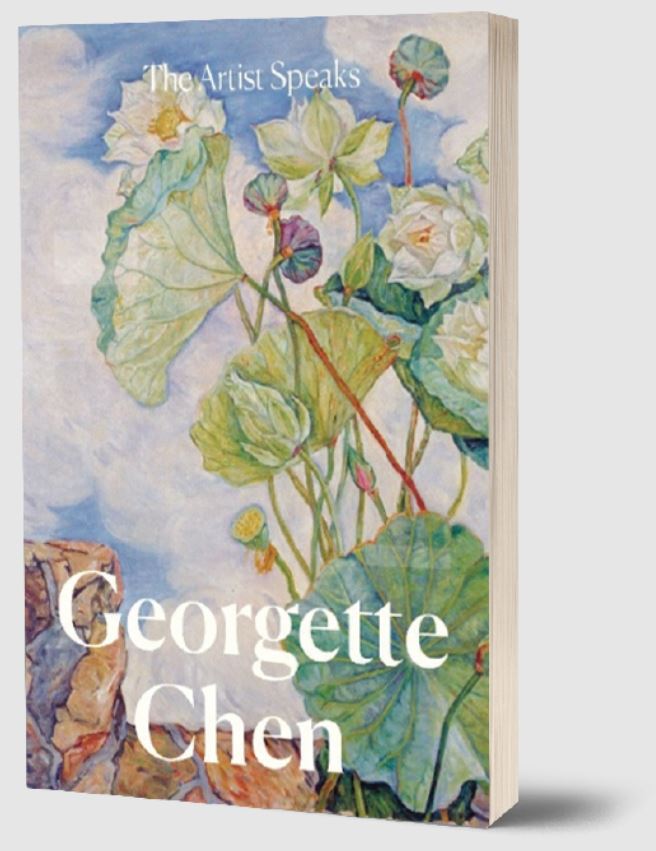

Georgette Chen is the first artist featured in The Artist Speaks, a series of books published by the National Gallery Singapore featuring visual artists who write.

The Artist Speaks: Georgette Chen draws upon the National Gallery’s extensive archive of materials on the artist dating from the 1930s to the 1970s. The collection consists of Chen’s journals, photographs, official records, newspaper clippings, personal belongings – including her beloved Hermes Baby typewriter and Malay books, among others – as well as carbon copies of some 1,000 letters that Chen had written to friends and family between 1949 and 1972.

The book also draws from materials held in the collections of the National Library and National Archives, including the oral history interview that art historian Constance Sheares conducted with Chen in 1988.25 Other resources in the National Library include a video on Chen produced by the Singapore Art Museum for the National Library Board in 2008;26 a biographical account of Chen’s life authored by Jane Chia in 1997;27 and the catalogue accompanying the 1985 retrospective exhibition of more than 170 of Chen’s works at the National Museum Art Gallery.28

Sara Siew is a writer and editor at the National Gallery Singapore. She is interested in the relationship between various forms of art, particularly intersections of the visual and the literary.

Sara Siew is a writer and editor at the National Gallery Singapore. She is interested in the relationship between various forms of art, particularly intersections of the visual and the literary.

NOTES

-

Chen, G. (1974, April 12). Georgette Chen to Dorothy and Lucille Lee [Letter]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. Dorothy Lee was the cousin of Eugene Chen, Georgette’s first husband, and Lucille was Dorothy’s daughter. Georgette often addressed Dorothy as her cousin, keeping in touch with her for many years after Eugene Chen’s passing; she once told her stepmother that Dorothy was “just like a sister” to her. ↩

-

Chen, G. (1953, September 7.) Chen’s personal transcript of her interview with Radio Malaya. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. ↩

-

Huang, L. (1959, August 30). I meet the remarkable Mrs Chen. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sheares, C. (Interviewer). (1988, November 2). Oral history interview with Georgette Liying Chen [Transcript of recording no. 000956/6/1, p. 6]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Chen, G. (1959, October 27). Georgette Chen to Hsu Mingmeo [Letter]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. Hsu was a friend of Eugene Chen’s and a medical doctor who modernised medicine in China. He was also the author of Dr Wu Lien Teh: The Plague Fighter. In the letter, Georgette was wishing Hsu success with a book he was writing, possibly a novel titled Five Years in Love. ↩

-

Sheares, C. (Interviewer). (1988, November 2). Oral history interview with Chen, Georgette Liying [Transcript of recording no. 000956/6/2, p. 16]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Chen, G. (n.d.). Recollections of Eugene Chen by his widow, notes for Dr Wu Lien-Teh’s book. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. ↩

-

Chen, G. (1953, March 25). Diary of 1953 [Diary]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. ↩

-

The word “interviews” came from Georgette. See Chen, G. (1961, February 15). Georgette Chen to Mr and Mrs Kan [Letter]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. ↩

-

Chen, G. (1961, February 15). Georgette Chen to Mr and Mrs Kan [Letter]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. ↩

-

Chen, G. (1961, January 2). Georgette Chen to Dorothy Lee [Letter]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. ↩

-

Chen, G. (1966, March 20). Georgette Chen to Inez [Letter]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. Inez was a relative of Eugene Chen’s whom Georgette referred to as cousin, and whom she kept in touch with for many years even after Eugene’s death. ↩

-

Chen, G. (1954, March 9). Georgette Chen to “friends” [Letter]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. ↩

-

Chen, G. (1961, February 6). Georgette Chen to unidentifiable recipients [Letter]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. ↩

-

Chen, G. (1960, December 24). Georgette Chen to Pauline Chen and her family [Letter]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. Pauline Chen was one of Chen’s close friends. They first met shortly after Chen arrived in Penang in 1951. Pauline stood by Chen throughout her divorce and subsequent relocation to Singapore, maintaining a decades-long correspondence with her. ↩

-

Chen, G. (1961, February 15). Georgette Chen to Dr and Mrs Kan [Letter]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. ↩

-

Chen, G. (1951, July 4). Georgette Chen to unidentifiable recipients [Letter]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. ↩

-

Chen, G. (1960, January 6). Georgette Chen to Joe [Letter]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. ↩

-

Chen, G. (1968, February 29). Georgette Chen to Inez [Letter]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. ↩

-

Chen, G. (1961, February 15). Georgette Chen to Dr and Mrs Kan [Letter]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. ↩

-

Chen, G. (1969, February 24). Georgette Chen to Dorothy Lee [Letter]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. ↩

-

Chen, G. (1963, February 11). Georgette Chen to Patricia Kennison [Letter]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. Kennison was one of Chen’s students at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts. ↩

-

Chen, G. (1967, May 17). Georgette Chen to Dorothy Lee [Letter]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. ↩

-

Chen, G. (1967, May 17). Georgette Chen to Dorothy Lee [Letter]. Retrieved from National Gallery Singapore. ↩

-

Sheares, C. (1988, November 2–1988, December 1). Oral history interview with Chen, Georgette Liying [Accession no.: 000956, 6 reels]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Cheong, K., & Wang, Z. (2008). Georgette Chen, Cultural Medallion recipient 1982 visual arts [Videorecording]. Singapore: Singapore Art Museum for National Library Board. (Call no.: RSING 759.95959 GEO) ↩

-

Chia, J. (1997). Georgette Chen. Singapore: Singapore Art Museum. (Call no.: RSING q759.95957 CHI). ↩

-

Georgette Chen retrospective, 1985. (1985). Singapore: National Museum. (Call no.: RSING 759.95957 CHE). ↩