Doctor, Doctor!: Singapore’s Medical Services

Milestones in Singapore’s medical scene – among other subjects – are captured through fascinating oral history narratives in a new book written by Cheong Suk-Wai and published by the National Archives of Singapore.

Life is a race against time. That much was clear to midwife Sumitera Mohd Letak after she helped a patient with dangerously high blood pressure who had just given birth. “She was bleeding like hell”, Sumitera recalled. “Her baby was gasping away and I had to suck mucus out of her baby’s mouth… I had to, by hook or by crook, take them to hospital.”

Alas, the mother, baby and midwife were on St John’s Island, which is about 6.5 km south of mainland Singapore. What was worse, it was the middle of the night. Sumitera added: “It was low tide, so I had to wake up the whole row of people in the quarters there to give me a helping hand.” The roused boatmen put the ailing mother and baby in a big sampan. Sumitera and the woman’s husband and mother climbed in too and they rushed to Jardine Steps at Keppel Harbour. Upon their arrival, the ambulance from Kandang Kerbau (KK) Hospital was nowhere in sight, so Sumitera left the woman in the care of her husband and the harbour police.

She flagged down a taxi and, with the baby in her arms and its grandmother in tow, rushed to KK Hospital. Sadly, the baby died there, but its mother was saved. “She was in hospital for three weeks because her blood pressure did not come down,” Sumitera recalled, adding that, fortunately, “the hospital treated her for free”.

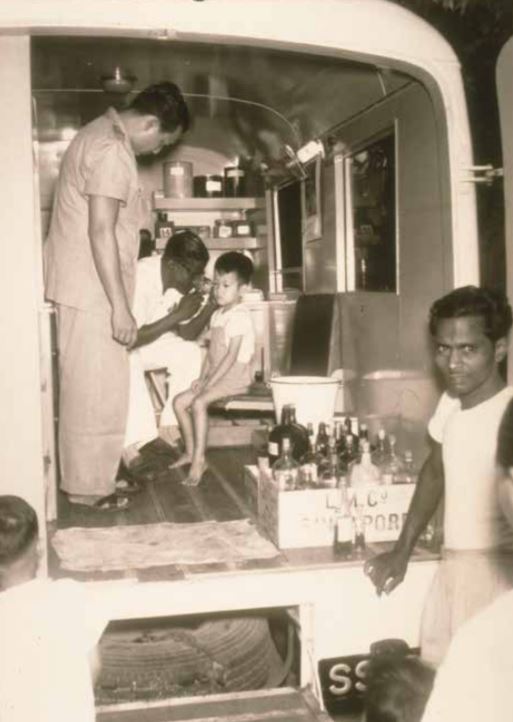

Sumitera, who was born in 1942, joined Singapore’s medical service as a midwife in the 1960s. She was among those in the Public Health Division who went out in “travelling dispensaries” twice a month. These dispensaries were ships kitted out with a pharmacy and medical equipment. With it, she visited Singapore’s outlying islets, including Semakau, Sebarok, Sudong and Seraya. The ship would berth itself some distance away from the shore, so she had to “go right up to the island in a motorboat, and then on to the community centre”.

Well into the 1960s, healthcare in Singapore was largely rudimentary, and not just on the nation’s outlying islands. Renowned gynaecologist Dr Tow Siang Hwa, who headed KK Hospital in the 1960s, said that at the time, “women walked into KK Hospital to have their 12th or 15th baby. Maternal complications of the most horrendous kind were a common experience. Maternal deaths from bleeding, from obstetric complications, from obstructed labour and from malpractice outside”. Speaking to the Oral History Centre in July 1997, Tow added: “All this is never seen again today.”

Singapore’s colonial administrators had provided free clinics for the needy, but these were few and far between. “The colonial government did give us free medical care at Outram Park outpatient clinic,” Chinatown resident Soh Siew Cheong recalled. In the 1960s, Tow recalled that fewer than 50 medical specialists practised in Singapore. Among those training to be one was Dr Yong Nen Khiong. Yong, who became a heart surgeon, recalled his college days at the University of Malaya in Singapore: “My medical cohort had 100 students. I took the bus to college every day… I was doing open heart surgery, practising on dogs.”

When Singapore attained self-government in 1959, its leaders had to overcome the most fundamental problems to give the nation a fighting chance to thrive. Founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew listed his Cabinet’s priorities as the setting up of defence forces; the provision of affordable public housing for all; the restructuring of the education system; more stringent family planning to curb over-population; and the creation of jobs for the tens of thousands who were unemployed then. Against all these pressing necessities, Lee judged the development of medical services and improvement in healthcare to be, perhaps, fifth or sixth on his list of to-dos. To compound matters, the government was strapped for cash.

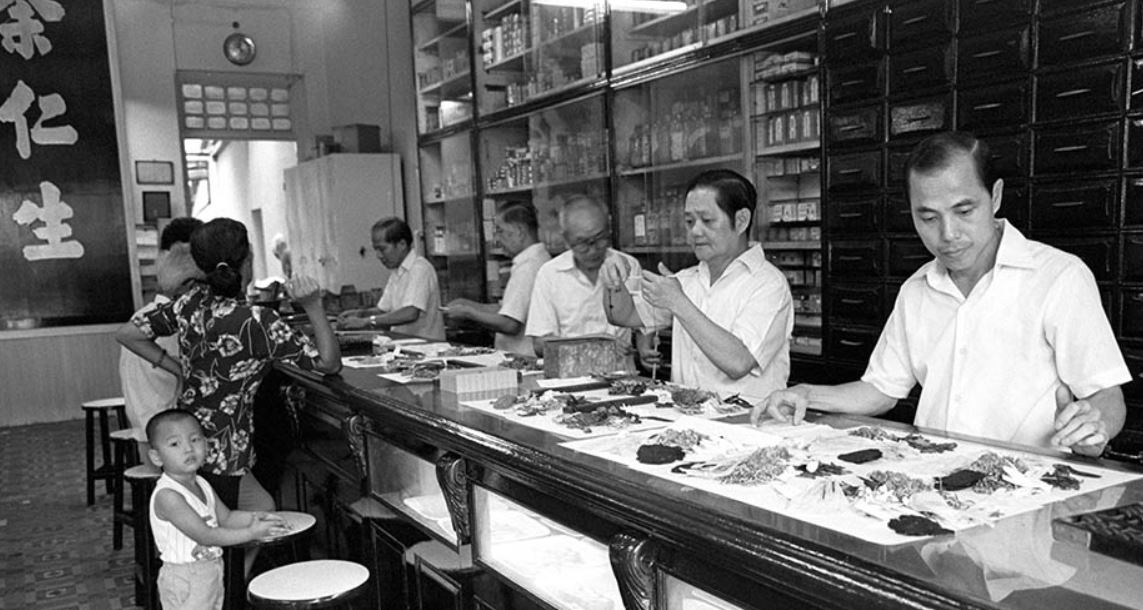

So Singaporeans made do, as they always had, with traditional folk medicine or, more often, store-cupboard remedies.

Eugene Wijeysingha, a former Principal of Raffles Institution, recalled that, as a boy, he cut his foot deeply while running around barefoot playing cops and robbers with his mates. “Blood was dripping and we went to someone’s house nearby,” he said. “They got a piece of cloth, put coffee powder and sugar on it, and wrapped the cloth round and round my foot. They hadn’t cleaned it first. But the wound healed; no tetanus or anything like that.”

Housewife Yau Chung Chii remembered well the kitchen-table wisdom passed down to her generation. Speaking in Cantonese, Yau said, for example, that pregnant women would avoid lamb, lest it gave their babies epilepsy. Upon giving birth, women would be fed pig’s trotters stewed with ginger and black vinegar, a dish thought to be effective in ridding their bodies of gas. She added that, however, some mothers told their doctors that they feared the vinegar would be so acidic that “it would melt their plastic stitches”. She added: “The doctors said, ‘No such nonsense. But if you believe it, don’t eat it’.”

The Malays had plant-based pastes and potions for women in confinement. Midwife Sumitera remembered two – param and jamu. “Param was a herbal concoction that you rubbed all over the mother’s body. It opened the pores, out of which impurities oozed… if you went near those using param, they smelled so sweet, [with] none of that fishy afterbirth smell which was caused by the poor flow of blood.”

Jamu was consumed to expel any blood clots after giving birth. “It’s a spicy herbal paste; you mixed it with water and drank it. It also helped the womb contract and return to normal size faster.” Sumitera never forgot how basic the islanders’ lives were even after Singapore became independent. Women and girls who were menstruating folded cloth, into which they crumpled newspaper, to stanch their bleeding. They would not heed Sumitera’s advice to use the sanitary pads that she distributed to them regularly. “They said they would keep it and use it only when they travelled to mainland Singapore.”

Singaporean Trailblazers

Amid this rough-and-ready approach to personal hygiene, some Singaporean doctors were already blazing trails in caring for patients.

Pathologist Prof Kanagaratnam Shanmugaratnam, for one, made sure that anyone in Singapore who had cancer could seek treatment for it without difficulty. Shanmugaratnam, whose son Tharman is a former Deputy Prime Minister of Singapore (and currently Senior Minister), set up a population-based cancer registry in 1968. At the time, he said, “there were hardly any private clinics in Singapore”. His fellow doctors, however, were “very supportive” in voluntarily notifying him and his team of anyone who developed cancer. He also personally scrutinised hospital discharge forms, as he put it, “so we did not miss a case”.

Another trailblazer was Dr Tay Chong Hai. In 1969, he was among the first Singaporeans to discover a disease that was later named after him. Tay’s Syndrome, as it became known, is a disease associated with intellectual impairment, short stature, decreased fertility, brittle hair, and dry, red and scaly skin, making an eight-year-old child look 80 years old.

In 1972, Tay made newspaper headlines when he saved many Singaporeans from over-the-counter pills and tonics that had life-threatening levels of arsenic. These included Sin Lak pills, which killed a woman who had taken them to cure her asthma. He fingered poverty as the root of such drug-related deaths. “It has to do with the cost of living”, he mused. “So such over-the-counter drugs are the first line of treatment.”

Fortunately, he noted, “Singapore is good with regulating” and so there were fewer deaths than there might have been from such self-medication.

Also, in 1972, Tay became the first doctor to identify Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease (HMFD) in Singapore. His wife, who is also a doctor, alerted him that she was treating many babies with mouth ulcers and rashes on their backs and legs. Jurong was the site of Singapore’s first HFMD epidemic in the 1970s, but the disease – caused by the coxsackievirus – soon spread islandwide. In 1974, together with six other doctors, Tay published a paper on the outbreak of the disease in the September issue of the Singapore Medical Journal.

SARS: All Hell Breaks Loose

The yearly panic about HFMD is nothing compared to the terror that seized many Singaporeans when the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) began infecting people here in March 2003.

The very contagious SARS, which originated in diseased civet cats in China, hit Singapore in March 2003, after air stewardess Esther Mok caught it from an elderly man in Hong Kong, with whom she had shared an elevator. Mok, also known as Patient Zero then, survived SARS but watched her parents, uncle and pastor die from the disease, which spreads through infected droplets.

Tan Tock Seng Hospital (TTSH) in Novena, where Mok had sought treatment, was designated SARS Central, the nerve centre for treating SARS patients, although the disease subsequently spread to Singapore General Hospital (SGH), Changi General Hospital and National University Hospital, in that order. Ironically, according to hospital administrator Liak Teng Lit, he first got wind of SARS at a dinner thrown by TTSH on 14 March 2003: “My friend Francis Lee had heard a conversation at his table during this dinner that staff of TTSH were falling sick.”

Healthcare officers moved as swiftly as the spread of the SARS virus after that and, Liak recalled, on 21 March 2003, the public finally heard about the epidemic. “Basically, all hell broke loose,” he said.

Bus driver Ang Chit Poh said the private bus business plunged such that most drivers switched to other trades for good. Those who remained in the business had to disinfect their buses day after day in the hope that it would restore the confidence of passengers who had abandoned this transport option. Traditional Chinese medicine practitioner Tan Siew Mong recalled the prices of popular herbs and roots going through the roof as, once again, people resorted to folk remedies as their shields against SARS.

Liak, who was then Chief Executive Officer of Alexandra Hospital – the only Singapore hospital whose patients did not die of SARS – recalled how landlords were so fearful, they kicked out nurses who rented their rooms. He recalled: “They had no place to stay.” So his staff and the hospital’s volunteers cleared a rundown former nursing quarters within the hospital’s grounds to house the stranded nurses.

Liak ordered new beds and furnishings for them from IKEA, the Swedish flat-pack furniture giant. Enter unsung hero Philip Wee, who was then General Manager of IKEA in Singapore. “He and his team personally brought and installed the beds in the hospital,” Liak said, his voice breaking as he recalled this. “We tried to pay for the beds, but they said, ‘Compliments from IKEA for helping the country fight SARS’.”

Once the quarters were fully habitable, Liak invited Jennie Chua, then General Manager of Raffles Hotel – and the first woman to have held that post – to, as he put it, “declare Hotel Alexandra open”.

Besides IKEA’s Wee, Liak was also very impressed with Ho Ching, the Chief Executive Officer of Temasek Holdings and wife of current Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong. He recalled Ho updating everyone concerned about the SARS situation in various countries “late into the night”. “She was also very creative,” he recalled. “People were worried about Malaysian motorists coming into Singapore, so she said why not set up a drinks stall with thermo-scanners, so that we could check the motorists for fever while they drank their liang teh (cooling tea).”

For his part, Liak – who usually did not walk around the hospital grounds much – made it a point to stroll through its corridors two or three times a day “to show confidence” to all. Things were, nevertheless, tense. He tried to ease it with some black humour. “I said, ‘If we die, it’s game over. If we live, COEs will be cheap and property prices will crash, so we will be able to buy bungalows on the cheap’.”

Liak realised that Singaporeans were in the grip of such fear because they knew next to nothing about SARS, and their imagination was working overtime. So he partnered the South West Community Development Council in a campaign to demystify the coronavirus that causes SARS. They worked with a cartoonist to depict the virus as a silly creature with a crown, and then got members of parliament and ministers to “whack” an effigy of this cartoonish creature.

He and his colleagues also exhorted everyone to wash their hands as often as they could. “If you can’t do anything, you feel helpless,” he mused. “So when you wash your hands, you feel better.” This is how Liak and his team boosted community morale during the crisis. Liak, in fact, believed that that rigorous handwashing saved his colleagues’ lives. “We actually had four patients with the SARS virus at Alexandra Hospital – they even coughed in the faces of my staff.” Not one among them succumbed to the virus, though. Many called them “lucky”, but Liak said it was more likely thanks to their vigilance and, yes, hand-washing throughout.

While everyone in Singapore’s healthcare system was reminded repeatedly to don protective masks and gowns, and keep washing their hands, some chafed against the sheer inconvenience of it all. Nurse Loo Yew Kim, who began her career at Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital in 1969 and worked there until she retired more than 40 years later, was at first peeved at the nagging of younger doctors for her and her fellow nurses to wash their hands after every step they took in caring for patients. “I really resented that,” she recalled in Mandarin in 2014. “We were by then in our 50s and 60s, so it was not as if we didn’t know that we should wash our hands.”

Loo and other nurses also fumed at having to don protective gear every minute of every day during the SARS epidemic. “Sweat would be dripping down my face from the mask,” she huffed. It was all so inconvenient, she added, that at some points, she would just fling her mask aside as it kept getting in the way of saving lives. “I will never forget the SARS period,” she stressed.

In June 2003, SARS was finally contained in Singapore, but not before claiming the lives of 33 among the total of 238 reported SARS patients.

Liak explained that SARS illustrated how much the world had changed due to globalisation. “Germs will always mutate and, often, viruses exchange material with human beings and animals… but in the past, whenever it mutated and killed an entire village, it could not spread after that because it had nowhere to go. But because transport became globalised, SARS could go from a Guangzhou village [in China] to towns and then cities. That is how dangerous the world has become.”

Worse, he added, people were now eating more meat, leading to increasingly intensive animal farming, which was unhealthy and stoked the spread of viruses which, once mutated, would be very hard to curb.

Prof Tan Ser Kiat, who was SGH’s chief during SARS, mused: “If a terrorist infected himself with smallpox, the incubation period of the virus would be long enough for him to mingle with everyone else. Smallpox would then spread like wildfire. This is what we are afraid of.” That was because, unlike droplet-borne SARS, smallpox is air-borne, meaning “I wouldn’t know who has got it until it’s too late,” he said.

The Goats That Saved Lives

More than most countries, perhaps, Singapore has had an excellent track record of mounting successful health campaigns. Among its biggest wins by far has been the eradication of diseases such as polio, diphtheria and rheumatic heart disease.

Diphtheria, in particular, was endemic in Singapore as tuberculosis was in the early half of the 20th century. The person to thank for its eradication is Prof Ernest Steven Monteiro. During the Japanese Occupation, Monteiro was in charge of Middleton Hospital, which was TTSH’s infectious diseases wing. The Japanese had taken two of his brothers away, and he never saw them again. He thinks the Japanese spared his life because “they were very short of doctors… and also very health-conscious, especially about infectious diseases such as diphtheria”.

At the time, Monteiro was among the very few doctors in Singapore specialising in the study of infectious diseases. He hit upon a solution to cure diphtheria after reading a book in which a doctor had tried to produce an anti-diphtheria serum by injecting the diphtheria organism into a goat named Mephistopheles. In the play Faust by German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Mephistopheles was an agent of Satan.

Monteiro tried that same experiment. After cultivating diphtheria, he extracted its toxins and injected that into the necks of goats. Then, once the goats were producing serum to combat the toxins in them, Monteiro extracted the serum from the goats and injected that into a child with severe diphtheria. The child recovered.

In 1958, Monteiro introduced the oral polio vaccine in Singapore, developed by American medical researcher Albert Sabin. Some 250,000 children were immunised against the disease, which was endemic then. This was despite much opposition from his compatriots in medicine, as the vaccine had not been tested on a large population in the United States. The vaccine, however, proved effective in blocking the poliovirus and Singapore became polio-free.

His son, Dr Edmund Hugh Monteiro, who once headed TTSH’s Communicable Disease Centre, said that despite his father’s diphtheria breakthrough during World War II, the disease was “a growing problem” in Singapore from the mid-1950s. This was, he added, in spite of doctors’ pleas to parents to get their children immunised against diphtheria. In the 1960s, he recalled, “only 55 per cent of children had that immunisation”. To eradicate the scourge, the younger Monteiro knew the immunisation rate had to be at least 90 percent.

So, in 1962, the government made immunisation against diphtheria compulsory on pain of paying a $2,000 fine, a sum too high for most families in those days. “As far as I can remember,” said the younger Monteiro, “no parent has ever been brought to court and fined”. Better yet, he noted, once a child turned up at a doctor’s for immunisation, he or she would most likely accept being immunised against tetanus, polio and so on. In this way, he said, Singapore soon eradicated diphtheria. He recalled further: “In those days, when they published details about the immunisation programme in The Straits Times, immunisation teams would be present for about a week in housing estates.

“And these nurses would actually climb the stairs or go up in lifts and tell parents there, ‘Bring your children down for immunisation.’ That was the sort of service that was provided – on your doorstep and for free. That set the stage for these childhood diseases to be eradicated.” By 1977, he recalled, diphtheria and polio had become things of the past for Singaporeans.

Dr Koh Eng Kheng, a doctor in private practice, said the government’s anti-diphtheria drive was a fine example of how concerted public health campaigns had to be. Quoting former American President Theodore Roosevelt, he said the success of such campaigns hinged on the government penalising anyone who tried to dodge immunisation. “You cannot soft-pedal these things,” Koh said.

Lawyer Nadesan Ganesan, a former chairman of the Football Association of Singapore, remembered government nurses vaccinating him against cholera during the Japanese Occupation, which was another illness that plagued Singapore right into the post-war period and into the 1970s. “There were only two or three nurses vaccinating us, and their needles were blunt to begin with. You could hear the sound ‘tok’ whenever they poked your arm… because the needle was so blunt, our arms swelled and we were all sick for three days. But we recovered lah and it was good because they helped us not get cholera.”

In 1984, measles struck Singapore in a big way. The government ordered the compulsory immunisation against measles and, once again, measles went the way of diphtheria and polio.

Unbeknownst to Singapore’s medical service, it was about to have another terrifying battle on the cards, against which immunisation was powerless – Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS).

Could Mosquitoes Give Me AIDS

Edmund Hugh Monteiro remembers Singapore’s very first AIDS patient. It was a man admitted to then Toa Payoh Hospital in 1986 for fever and diarrhoea, and shingles to boot. But the hospital transferred him to the Communicable Diseases Centre – where Monteiro was the Director – when they found that he had a salmonella infection. Monteiro thought about how the man’s immune system could have broken down so badly. He tested the man for AIDS. “And it was positive”.

It was not long before the centre’s senior staff wanted to transfer out because they feared having to care for AIDS patients. “AIDS was something which they were not used to and it was too terrifying. Some among them were not personally panicking, but their family members were saying, ‘You better get out.’ So there was, unfortunately, a lot of ignorance as to how the disease was spread.” That was triggered by the government designating his centre in 1985 as the lone place in Singapore to treat AIDS patients.

The flurry of fearful queries continued from his staff. “If the mosquito bites an AIDS patient and then bites me, will I get HIV?” was the biggest worry. Monteiro said that what he found “most assuring” about AIDS was that, apart from sexual intercourse with the AIDS patient, “you’d have to stick yourself with a needle” to be infected. “In other words,” he said, “you didn’t have to be gloved, gowned and masked whenever you went to see the patient”. In fact, he noted, it was far easier to be infected with Hepatitis B and C then it was to get AIDS.

The stigma against its patients, however, persisted. Monteiro especially rued the unfeeling attitude of some doctors towards AIDS sufferers. “We talk to people very early in their medical careers, tell them that if they are going to become doctors, sometime in their career, they are going to have to treat a person with AIDS. It’s unlikely that you will go through a medical career for 20, 30 years without having to manage a person with AIDS.”

There was, he recalled, “one young doctor who wanted to specialise in infectious diseases ‘as long as I don’t have to manage AIDS patients’. So we closed the door on that person and said, ‘You’d better find another discipline if you can’.”

First, Do No Harm

The case of that young doctor with an aversion to AIDS patients begs the question: what makes a good doctor?

Edmund Hugh Monteiro recalled his father giving him this advice: “You want to do medicine? Okay, two things. One, you never stop learning. Two, you may have to sacrifice your lunch… I think what he meant was that patients can sometimes be overpowering in their demands.”

He then cautioned: “You need to put them off at certain stages, and not make it out that medicine is a profession where everyone is to be heroic and self-sacrificing. You need to draw a line, I mean, you will just be burnt out with patients’ problems… if I draw a line somewhere, I can actually function better than if I just didn’t know what I was supposed to do.”

Kanagaratnam Shanmugaratnam the pathologist thought that a doctor’s empathy for his patients’ predicaments was a hallmark of great medicine. “We inspire them to be interested in the nature of disease because that’s how they can be good surgeons or physicians. To understand suffering, to speak freely, to ask us things which require clarification.”

He added: “And it’s a huge pleasure to be able to solve problems for the medical students. Medicine is not a nine-to- five job; you cannot be a specialist with that kind of mentality. So one has to work long hours, studying in the evenings, keeping up with medicine.”

First Test-Tube Baby

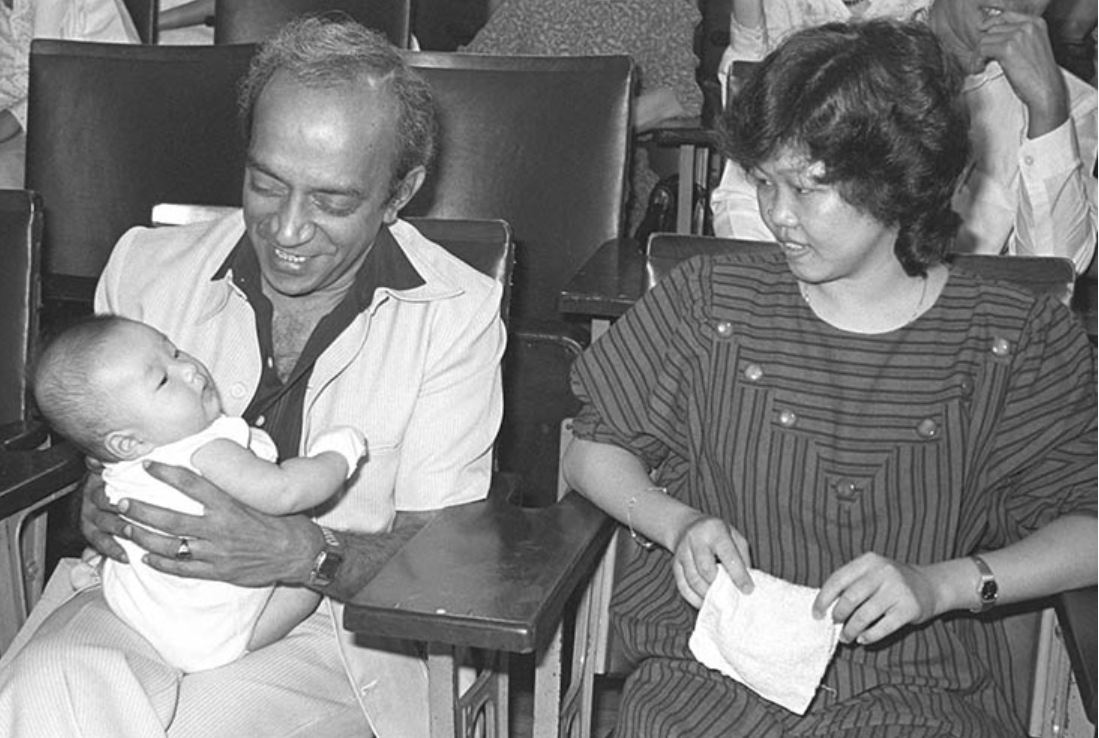

For many years, the parents of Samuel Lee Jian Wei could not conceive a child naturally. Fortunately, they were in an age when science had made much progress. On 25 July 1978, Louise Joy Brown, the first baby created from sperm fertilising a human egg in a test tube, was born in Manchester, England.

Back in Singapore, the brilliance of surgeon Prof S.S. Ratnam meant that this artificial method of conception, known as in-vitro fertilisation (IVF), was available to the Lees from the early 1980s.

Samuel was born on 19 May 1983 at KK Hospital. He was a triumph for medicine in Singapore and so captured everyone’s imagination the moment he came into the world. Samuel recalled: “From the age of three or four, I kept hearing the words ‘IVF’ and ‘test-tube baby’.”

At the age of six, he finally met Ratnam the surgeon who had made his birth a reality. “He asked me some questions, like ‘How have you been doing?’ He was quite friendly and treated me very nicely… When I was young, I was quite shy, but he made me laugh so I felt very comfortable with him.”

Given a choice, though, Samuel would rather not have been Singapore’s first test-tube baby. “It’s so that I would not get so much unwanted attention,” he rued. As recently as 2015, he was in the spotlight again, as his profile was included in Singapore’s official SG50 book, Living the Singapore Story.

Access to Ratnam’s September 1997 interview with the Oral History Centre is restricted, so his views on Samuel and other subjects cannot be quoted here for now. But fellow doctor Tow Siang Hwa, who handpicked Ratnam to succeed him at KK Hospital from 1969, can shed light on how skilful Ratnam was. Speaking in July 1997, Tow recalled: “S.S. Ratnam was my handpicked trainee… He was intelligent and had the makings of a professor.” In 1969, when Tow left KK Hospital to start his own practice, he told Ratnam: “Ratnam, I am going to leave, but you will succeed me.

“That was the vision I had, that he would succeed me,” Tow mused. “By then, the ship was high and sailing; the groundwork had been done and now it was for him to keep it going. And he sailed the ship well because in no time, he was reaching the highest levels.”

Tow, who helmed KK Hospital in the 1960s, had raised the reputation of the nation’s medical capabilities. In 1960, his expertise in molar pregnancy – in which an embryo is abnormal, resembling a cluster of grapes, and cannot develop fully – stunned an expert at Leeds University, who encouraged him to submit the discovery for a prestigious lecture in Britain. Before long, inspectors from Britain’s Royal College of Obstetrics & Gynaecology recognised KK Hospital as being of the highest medical standards, from the way it ran its operations to how it cared for patients. Tow said: “Now this was a major, major advance. It meant that obstetrics & gynaecology were on a par with medicine and surgery. So we were able to train our specialists locally.

“So, from that day, instead of having five specialists for the whole population of Singapore, today, in 1997, we have 200 specialists.”

This essay is an extract from the book, The Sound of Memories: Recordings from the Oral History Centre, Singapore, published by the National Archives of Singapore and World Scientific Publishing. The hardcover, paperback and ebook retail for $46, $28 and $19.95 respectively. The book is also available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 959.57 CHE and SING 959.57 CHE). The ebook is available for loan on NLB OverDrive.

Cheong Suk-Wai is a lawyer by training and a writer by choice. A former ASEAN Scholar and Thomson Foundation Scholar, she has been a construction litigator, a journalist and a public servant.

Cheong Suk-Wai is a lawyer by training and a writer by choice. A former ASEAN Scholar and Thomson Foundation Scholar, she has been a construction litigator, a journalist and a public servant.

LIST OF INTERVIEWEES

- Ang Chit Poh (Accession no.: 004159) was a bus driver who witnessed how private bus business were affected during the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) crisis from March till July 2003.

- Edmund Hugh Monteiro (Accession no.: 001956) treated many among Singapore’s first HIV/AIDS sufferers. He is former Director of the Centre for Communicable Diseases. He got his smarts, wisdom and compassion from his father, the trailblazing doctor Ernest Steven Monteiro.

- Ernest Steven Monteiro (Accession no.: 000488), the father of Edmund Hugh Monteiro, was the first Asian to hold the Chair of Clinical Medicine at the University of Malaya, and later Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at the same university. He succeeded in cultivating an anti-diphtheria serum in goats.

- Eugene Wijeysingha (Accession no.: 001595) began his career as a teacher at Raffles Institution (RI) in 1959. He was later Principal of Temasek Junior College from 1980 till 1985 and then Principal of RI from 1986 till 1994, when he retired.

- Kanagaratnam Shanmugaratnam (Accession no.: 001562) was a pathologist who came to be known as Singapore’s “Father of Pathology”. His son Tharman was Singapore’s Deputy Prime Minister from 2011 till 2019.

- Koh Eng Kheng (Accession no.: 002000) was among Singapore’s most beloved family physicians. He opened Chung Khiaw Clinic in 1957 and was still seeing patients a few months before his death in July 2006. In 1972, he was appointed President of the Singapore Medical Association and was later President of the College of General Practitioners Singapore.

- Liak Teng Lit (Accession no.: 003867) is the former Chief Executive of Toa Payoh Hospital, Changi General Hospital, Alexandra Hospital and Khoo Teck Puat Hospital. Under his watch, Alexandra Hospital had the fewest patients suffering from Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) when the epidemic hit Singapore in 2003.

- Loo Yew Kim (Accession no.: 003501) grew up in the grounds of Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital, where her foster parents were cleaners. Upon leaving school, she became a patient care assistant – a post we would now refer to as a nurse – at the hospital.

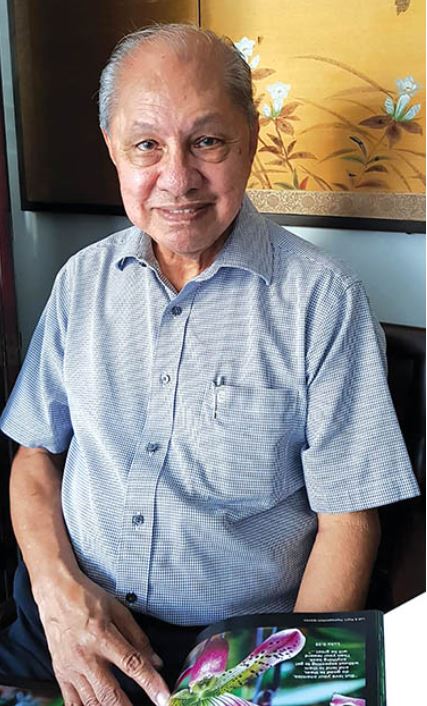

- Nadesan Ganesan (Accession no.: 003279) is a lawyer and former Chairman of the Football Association of Singapore. He survived the Japanese Occupation, and vowed never to touch tapioca or sweet potato again.

- Samuel Lee Jian Wei (Accession no.: 003407) is Asia’s first test-tube baby, born on 19 May 1983 to a security supervisor and a secretary. He was named Samuel by Professor S.S. Ratnam, the surgeon who carried out invitro fertilisation to aid his conception.

- Soh Siew Cheong (Accession no.: 003274) grew up in Chinatown in the days when gangsterism was rife. He trained as an engineer and was among the pioneering batch of local civil servants in Singapore.

- Sumitera Mohd Letak (Accession no.: 001915) started out as a midwife, travelling to and from mainland Singapore to the outlying islands to care for women there. She later took up nursing and continued to help mothers in need, winning volunteerism awards along the way.

- Tan Ser Kiat (Accession no.: 003084) was the Group Chief Executive of SingHealth from its inception in 2000 till 2012. An Emeritus Consultant in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the Singapore General Hospital, he is also President of the Singapore Medical Council.

- Tay Chong Hai (Accession no.: 002537) is the first Southeast Asian to have had a disease named after him – Tay’s Syndrome. In the late 1990s, he discovered another disease, eosinophilic arthritis. With his wife, Dr Caroline Gaw, they first alerted Singaporeans to the existence of Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease.

- Tow Siang Hwa (Accession no.: 001920) was among Singapore’s pioneering gynaecologists. As Head of what is now KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital from 1960, he secured accreditation for it from the prestigious Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Britain. He later left for private practice and set up Tow Yung Clinic.

- Yau Chung Chii (Accession no.: 000427) was steeped in Chinese kitchen wisdom. She was by turns a salesclerk at Daimaru departmental store, a telephonist and a typist.

- Zong Nen Khiong (Accession no.: 003548) was among the Chinese residents of Singapore who settled in the Japanese wartime settlement of Endau in Johor in the mid-1940s. He later became a heart surgeon.