To Wreck or to Recreate: Giving New Life to Singapore’s Built Heritage

Nearly 70 years have passed since a committee was set up to look into the preservation of buildings and sites with historical value. Lim Tin Seng charts the journey.

Historic and nationally significant buildings are among Singapore’s most important cultural assets, and the protection of its built heritage is an integral component of the nation’s overall urban planning strategy.

The beginnings of the city’s preservation efforts can be traced back to 1950, when a committee was set up to look into the preservation of individual buildings and sites with historic value. In the ensuing decades, these efforts grew to encompass more concrete initiatives that emphasised both the conservation and preservation (see text box at the end of this article) of entire areas, along with a greater focus on heritage buildings and their relationship with the surrounding built environment.

Early Colonial Efforts

The idea of conserving and preserving Singapore’s built heritage is not a recent initiative. It did not emerge with the unveiling of the Urban Redevelopment Authority’s Conservation Master Plan in 1986, nor did it surface when the Preservation of Monuments Act was enacted earlier in 1971. Its history in fact goes back to the postwar period when the colonial government formed the Committee for the Preservation of Historic Sites and Antiquities in 1950.1

Headed by Michael W. F. Tweedie, who was then Director of the Raffles Museum, the committee was tasked to recommend ways to maintain the tomb of Sultan Iskandar Shah, the last ruler of 14th-century Singapura, and a 19th-century Christian cemetery. Both these sites on Fort Canning Hill were in a dilapidated state due to years of neglect and exposure to the elements.

In 1951, the committee concluded that “the best way of commemorating the people who were buried there” was to turn Fort Canning into a public park.2 As part of the scheme, crumbling tombstones from the Christian cemetery were salvaged and embedded into the walls of the new park, while tombs that were still intact, such as that of pioneer architect George D. Coleman’s, were preserved for their historical value.3

In 1954, the committee was given another assignment. Headed by members Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill and T.H.H. Hancock – curator of zoology at the Raffles Museum and senior architect of the Public Works Department respectively – the team was asked to draw up a list of historic sites in Singapore.4 The purpose was to put up plaques at these sites describing their significance. The plaque inscriptions would be in English but if the site was of Malay or Chinese origins, then Malay and Chinese text would be correspondingly inserted alongside the English inscription.

The committee identified some 30 sites, most of which were built in the 19th century.5 These included secular buildings and structures like Victoria Theatre, Elgin Bridge, H.C. Caldwell’s House, 3 Coleman Street (also known as Coleman House) and Old Parliament House, as well as places of worship belonging to the major religions practised in Singapore, such as St Andrew’s Cathedral, Cathedral of the Good Shepherd, Sri Mariamman Temple, Thian Hock Keng Temple and Masjid Hajjah Fatimah. Iskandar Shah’s tomb and the gateways of the Christian cemetery at Fort Canning were also included in the list.6

Besides identifying historic sites, the committee was also keen to restore historic buildings and preserve them for posterity. However, it admitted that the endeavour would be difficult and could only be undertaken if there were sufficient funds. Tweedie noted that many of the buildings were owned privately, which meant that the government would have to pay exorbitant sums to the owners in order to acquire them.7

Despite the lack of funds, the need to preserve historic sites was included in the urban planning process when the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) – predecessor of the Housing & Development Board – was tasked to “prepare… and amend from time to time a list of ancient monuments… and buildings of historic and/or architectural interest” for the 1958 Master Plan.8 Although the list did not guarantee preservation, but only the consideration for the possibility of preservation, the 1959 Planning Ordinance nevertheless provided for the enactment of rules relating to the protection of the sites and buildings identified on the list.9

To compile the list, the SIT took into account the age of the sites as well as their historical and architectural significance. It also consulted members of the Committee for the Preservation of Historic Sites and Antiquities, including Gibson-Hill and Hancock.10 For this reason, the SIT’s heritage list was quite similar to the one drawn up by the preservation committee, with 20 of the 32 sites identified by the SIT found on the earlier list. The new additions included Outram Gaol, 3 Oxley Rise (or Killiney House), Kampong Radin Mas cemetery and the Indian cemetery in Geylang.11 SIT’s list, like the one drawn by the preservation committee, comprised both secular and non-secular sites and buildings, underlining the deference the colonial government accorded to the religions observed by its resident communities (scroll down to the bottom).

SIT’s heritage list was drawn up in consultation with a society known as Friends of Singapore. The society was founded in 1937 by the well-known lawyer Roland St John Braddell and other leading public figures, including Song Ong Siang, a prominent member of the Straits Chinese community who later served as the society’s first president. The society had included in its charter “the preservation of historical buildings and sites” as one of the projects it could initiate “for the embellishment or the cultural improvement of Singapore.”12

During its formative years, however, Friends of Singapore achieved little in terms of conserving Singapore’s historic landmarks. It was only in 1955 that the society made some progress when it launched a public campaign calling for the preservation of Coleman House (built in 1829 as the private residence of prolific colonial architect George D. Coleman) and the commemoration of the 1942 battle site in Pasir Panjang, where the Malay regiment fought the Japanese Army.13

Arguing that the scheme was for the “improvement of the city and the benefit of the people”, the society planned to restore Coleman House and turn it into “a home of the arts”, where exhibitions and concerts could be held. To support its case, the society published a pamphlet detailing the historical significance and the architectural value of the house.14 As for the Pasir Panjang battle site, the society opposed the War Department’s plan to construct a mess hall there and recommended that a commemorative park be created instead.15

Besides Coleman House and the battle site, Friends of Singapore also made public calls for nature sites such as Bukit Timah and Ulu Pandan to be preserved and turned into proper nature parks to attract tourists.16 In addition, in 1957, the society came out to support the SIT when Chartered Bank Trustee Company, the owner of Killiney House at 3 Oxley Rise – built by Thomas Oxley, surgeon-general of the Straits Settlements – tried to have the 1842 property removed from the 1958 Master Plan heritage site list as he was worried that the “ancient monument” status of the house would affect its sale price.

During the inquiry, the society gave evidence to explain why Killiney House should be preserved, pointing out that it was one of the last surviving “planter’s home” from the 1840s, and among the first residences built in the island’s interior. In addition, the house had a dovecote to house pigeons and stables for horses, which made it architecturally unique in the Straits Settlements.17

Demolition and Urban Renewal

When the People’s Action Party (PAP) came into power in 1959, preserving Singapore’s built heritage was initially accorded little, if any, attention. The new government had other more pressing concerns, chief of which was to improve the housing situation.18

It was estimated that in 1960, a quarter of a million people were living in overcrowded slums in the 688-hectare city centre, and another one-third in squatter areas – all of whom urgently needed rehousing. Many structures in the city centre were at least a century old and falling apart or had been crudely built by the squatters. Besides being potential fire hazards, these homes also lacked proper ventilation and sanitation. In addition, most were only two or three storeys high, and thus made uneconomical use of valuable land.19

To solve the problem, the government launched an aggressive public housing programme in 1960 to build housing estates beyond the city centre. The Housing & Development Board (HDB) replaced the SIT, while the Urban Renewal Department (URD; the predecessor of today’s Urban Redevelopment Authority) was created as a department under the HDB to spearhead an urban renewal programme for redeveloping the central area.

In the initial years, urban renewal mainly concerned itself with the demolition of old buildings, clearing of slums, resettlement of the people from the city centre, and the planning of new buildings that maximised the redevelopment potential of the land. As the aim was “the gradual demolition of virtually the whole 1,500-odd acres of the old city and its replacement by an integrated modern city”,20 the priority to preserve historic sites was very low.

When the 1964 redevelopment of Precinct South 1 was rolled out, Outram Gaol, which was on the heritage list of the 1958 Master Plan, was demolished along with many colonial-era shop houses to make way for flats. In 1965, the privately owned Coleman House was razed to build the Peninsula Hotel, while other buildings, such as Raffles Institution and Killiney House, were pulled down in the 1970s to free up space for commercial projects.

In less than a decade after the urban renewal programme was officially launched in 1966, nearly 300 acres of the central area had been redeveloped.21 During the same period, the HDB built more than 130,000 flats in new housing estates. These provided accommodation for some 40 percent of the population, most of whom previously lived in the central area.22

A Move Towards Conservation, Rehabilitation and Rebuilding

The seemingly random demolition of historic buildings, however, did not mean that the government was completely unaware of the need to preserve the city’s historic sites. When it engaged Erik Lorange, a United Nations town planning adviser, to propose a long-term framework for urban renewal in 1962, the Norwegian suggested taking measures to “rehabilitate” suitable buildings instead of tearing them down.23 Similarly, when a second UN team arrived in 1963 to follow-up on Lorange’s work, it advised that urban renewal did not necessarily mean demolishing old buildings in favour of erecting new structures. Instead, the process should have three imperative aspects: conservation, rehabilitation and rebuilding.

The process of identifying areas worth preserving in Singapore, followed by a programme to improve such areas with a better environment as well as the demarcation of remaining areas to be demolished and rebuilt, was conceived based on the observation that the districts undergoing renewal were thriving instead of decaying. The three-member UN team emphasised that a “commitment [should] be made to identify the values of some of Singapore’s existing areas and build and strengthen these values”. This would include the “recognition of the value and attraction of many of the existing shophouses and the way of living, working and trading that produced this particularly Singapore type of architecture”. The UN team also added that preserving parts of the old city such as Chinatown would be beneficial as they could function as “escape hatches from sameness and order”.24

The recommendations raised in the 1963 UN findings were supported by Singaporean architects such as William Lim and Tay Kheng Soon. Notably, the Singapore Planning and Urban Research Group (SPUR) – an urban planning think tank founded by Lim and Tay as well as architect Koh Seow Chuan and others like Chan Heng Chee – published a response in the 1967 issue of its periodical, which noted that “redevelopment is necessary as part of the evolution of any City”. However, the think tank cautioned that the magnitude of redevelopment should be kept to a minimum and carried out using the “same three processes” of conservation, rehabilitation and rebuilding as proposed by the UN team.

More critically, on identifying buildings that were worthy of preservation, the SPUR emphasised that this should be “by reason of their historical, architectural or other special significance”, and the approach should be taken from the perspective of the local context rather than the Western definition, which tended to focus more on grandiose buildings and monuments. This way, even Singapore’s modest vernacular buildings, dismissed by some as insignificant, could be appropriately assessed for their historical significance.25

Perhaps one of the clearest signs that the government was mindful of the need to preserve Singapore’s built heritage came from the town planners themselves. In 1969, Alan Choe, who was then head of URD, wrote that although Singapore had only a “few buildings worthy of preservation” and that many of the buildings in the central area were “overdue for demolition”, urban renewal should not just be the “indiscriminate demolition of properties of historical, architectural or economic value”. Instead, town planners were urged to introduce preservation measures that would “sustain and improve the colourful character of Singapore”.26

In fact, the URD had already moved to preserve some buildings, including Hajjah Fatimah Mosque, in Stage 2B of the redevelopment of Precinct North 2B in 1967. This won praise from then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. In a letter to Choe, Lee wrote that he had read the preservation efforts “with satisfaction”, and commended Choe for taking steps on “preserving what little there is of historic interest and recording in pictorial form for posterity [the buildings that] must economically be destroyed”.27

The Creation of a Preservation Board

Although it was not publicly made known, Singapore’s town planners had been discussing with architects and academics on how historic sites should be preserved during the revision of the 1958 Master Plan.28 In 1963, the Committee on Ancient Monuments, Lands and Buildings of Architectural and/or Historic Interest was set up to review the 32 historic sites identified by the SIT back in the 1950s.

Comprising town planners, surveyors and representatives from the National Museum and the Singapore Institute of Architects (SIA) – such as the director of the National Museum, Christopher Hooi Liang Yin, and W.I. Watson from the SIA – the committee felt that the age criterion that the SIT used to select historic sites should be removed, and the cost of preservation added as a factor for consideration.29

In addition, the committee said that sites that had been rebuilt should be excluded from the list, while “sites of character” and “places or objects of interest to tourists”, including small monuments, be considered as historic sites.30 Based on this new selection criteria, the committee ended up removing some of the historic sites from the SIT’s heritage list. These included Coleman House, Raffles Institution, Outram Gaol, Killiney House and a number of places of worship as these had been substantially renovated or rebuilt.31 However, new ones – such as the Istana, Old Parliament House, City Hall, Telok Ayer Market, Tan Kim Seng Fountain, Lim Bo Seng Memorial and the Cenotaph – were added.32

Besides revising SIT’s list, the committee also began to “examine and recommend the manner of controlling or regulating development” at the identified historic sites. This included identifying the various forms of preservation, and resolving the problems of compensation and acquisition. As early as the first meeting, the committee agreed that the identified historic sites could either be preserved fully so that the complete structure was left intact, or partially such that only portions of it were retained. For sites that were “allowed to be demolished and replaced by more economic or intensive uses”, they would be preserved through documentation, i.e. “measured drawings” and photographs. Some of the sites that were preserved in this manner before they were demolished included Outram Gaol, Coleman House, Raffles Institution, Killiney House and the surviving corner of Ellenborough Building.33

At the outset, the committee also agreed that both funds and the means of acquiring the historic sites from private owners should be made available before preservation was carried out. As such, it proposed forming a national monuments trust with statutory autonomy. Backed by legislation, the trust would have the legal authority to carry out its functions – including the ability to acquire properties that had been identified as historic sites for preservation, raising funds and providing financial aid for preservation work, as well as carrying out activities to raise public awareness on preservation. In addition, the trust would recommend new sites for preservation and the most appropriate preservation methods to be used.34

In 1969, the government formally announced plans to set up a national monuments trust.35 Two years later, the Preservation of Monuments Board (PMB) was set up following the enactment of the Preservation of Monuments Act. The board was responsible for safeguarding specific monuments as historic landmarks that provided links to Singapore’s past. It identified buildings and structures of historical, cultural, archaeological, architectural or artistic interest, and recommended them for preservation as national monuments.

The PMB’s functions also included the documentation and dissemination of information on these monuments, the promotion of public interest in monuments, and the provision of guidelines and support on the preservation, conservation and restoration of monuments. The board’s definition of national monuments comprised religious, civic, cultural and commercial buildings.36

Among the first monuments to be gazetted by the PMB on 28 June 1973 were the Old Thong Chai Medical Institution, Armenian Church, St Andrew’s Cathedral, Telok Ayer Market (Lau Pa Sat), Thian Hock Keng Temple, Sri Mariamman Temple, Hajjah Fatimah Mosque and the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd.

In order to document information on the gazetted monuments, the board teamed up with the School of Architecture at the University of Singapore to produce a series of measured drawings. Comprising floor plans, elevation sections and other architectural details, these drawings were important as most of the gazetted monuments did not have plans that were drawn to scale. Thong Chai Medical Institution is the first monument to have its drawings completed in 1974. The rest were completed by 1977.37

From Historic Buildings to Historic Districts

Shortly after the PMB announced the first national monuments to be gazetted, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) – which replaced the URD in 1974 – began looking into the conservation and rehabilitation of entire areas and districts.38 This holistic approach took the preservation of Singapore’s built heritage to another level by providing protection not only to buildings of historical, architectural and cultural significance, but also to their traditional settings, thus allowing the distinct identity and character of an entire area to be preserved.

The first holistic conservation projects that the URA undertook were the rehabilitation and conversion of 17 Melaka-style terrace houses on Cuppage Road for commercial use, 14 Art Deco colonial shophouses on Murray Street as restaurants, nine Tudor-style former government quarters on Tanglin Road as offices and a shopping mall, and six colonial shophouses on Emerald Hill Road as a pedestrian-only mall with a distinct Peranakan flavour.39

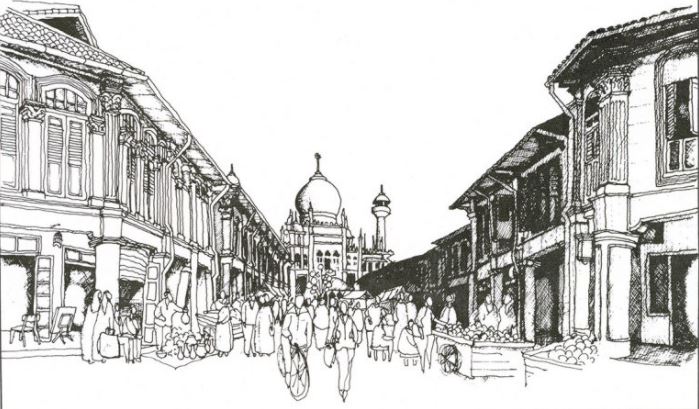

In its 1982 review of the urban design structure plan of the city centre, the URA expanded its holistic conservation approach by coming up with a conservation blueprint. The plan, which was unveiled in 1986, identified six historic areas for conservation: Chinatown, Kampong Glam, Little India, Singapore River, Emerald Hill and the Heritage Link – the last being a civic and cultural belt comprising Empress Place, Fort Canning Park and Bras Basah Road.40 Covering four percent of the central area, the blueprint aimed to preserve the architecture and ambience of these areas through various means. These included improving pedestrian walkways and signage, as well as organising activities that would raise awareness of the character of these places.41

The URA introduced conservation guidelines to help developers conserve their properties while, at the same time, preserving the historical character of the area.42 In 1987, the URA embarked on a project to restore 32 dilapidated shophouses in Tanjong Pagar. As part of a larger programme to rejuvenate all the 220 state-owned shophouses in the vicinity, the project was considered the first to show concrete proof that it was both technically possible and commercially viable to restore old shophouses that occupy several streets in an entire conserved area. The project also sought to “educate the public and industry on the importance of heritage conservation by revealing the buildings’ long hidden beauty”.43 The URA selected the shophouse at 9 Neil Road to be restored first as the prototype. This set the standard on how restoration work should be carried out on the other shophouses in Tanjong Pagar and the conserved areas.

In subsequent years, the conservation blueprint was implemented through a comprehensive master plan launched in 1989, which saw Chinatown, Little India, Kampong Glam, Emerald Hill, Cairnhill, Boat Quay and Clarke Quay gazetted as Singapore’s first historic districts.44 At the same time, the Planning Act was substantially amended in the same year to enable the URA to function as the national conservation authority. The amendments included empowering the URA to identify areas of historical significance for conservation, set guidelines on how conservation works should be carried out, and act as the approving authority for developers who wanted to carry out works on their properties located in conservation areas.45

The Way Forward

Since the first conservation areas were gazetted in 1989, the work of the PMB and the URA have continued unabated. The PMB remained a statutory board under the Ministry of National Development until 1997 when it was transferred to the Ministry of Information and the Arts (now Ministry of Communications and Information). In 2009, the PMB merged with the National Heritage Board, and was renamed Preservation of Sites and Monuments (PSM) in 2013.46

Between 1973 and 2018, the number of gazetted national monuments increased from eight to 72. In addition to the monuments, the PSM also erected heritage markers at places of historical significance describing important events and key personalities associated with the place.47

As for the URA, it is continuously identifying new areas to be conserved and updating its conservation guidelines to improve the standard of conservation works. As at 2018, some 7,000 buildings in more than 100 locations have been conserved.48 An integral part of the URA’s conservation strategy is to ensure that the essential architectural features and spatial characteristics of the buildings are retained while allowing flexibility for adaptive reuse, i.e. the process of reusing an existing building for a purpose other than what it was originally designed for. In fact, the URA’s fundamental conservation principle – applicable to all conserved buildings, irrespective of scale and complexity – is maximum retention, sensitive restoration and careful repair.49

To recognise monuments and buildings that have been well restored and conserved, the URA launched the Architectural Heritage Awards in 1995. The annual awards honour owners, developers, architects, engineers and contractors who have displayed the highest standards in conserving and restoring heritage buildings for continued use. The awards also promote public awareness and appreciation for the restoration of monuments and buildings in Singapore.50 The first recipients of the awards in 1995 were River House in Clarke Quay, Armenian Church, 77 Emerald Hill Road, 161 Lavender Road, 149 Neil Road and 11 Kim Yam Road. To date, more than 100 buildings, including the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd, Sultan Mosque and Chijmes, have received the awards.51

In addition, the URA launched an annual event in 2017 that celebrates Singapore’s built heritage and sensitively restored buildings. Known as the Architectural Heritage Season, the festival organises a variety of activities – talks, seminars, exhibitions and tours – for the public. For the inaugural festival, the URA invited community partners such as professionals, students and volunteers, to conduct guided tours and to share their expertise in technical restoration.52

In many countries, conservation efforts initially viewed buildings as individual entities with scant attention paid to the relationship between buildings or to the relationship between buildings and their immediate surroundings. The same thinking applied to Singapore. While a building conservation policy had existed in Singapore since 1950, the policy for conserving specific areas only developed from the 1960s onwards. The first initiatives to holistically conserve areas took place in the 1970s and early ’80s when the URA embarked on a several small projects to restore rows of colonial shophouses in Murray Street, Cuppage Road, Emerald Hill and Tanglin Road. This subsequently turned into a full-scale master plan that saw larger areas such as Chinatown, Kampong Glam and Little India designated as conservation areas.

Today, Singapore continues to carry out its mission to protect its built heritage and the conservation of historic districts through the twin efforts of the PSM and URA. While what has long met the wrecker’s ball cannot be rebuilt, the future holds bright for historically important buildings and heritage areas that have survived the ravages of time.

The term “conservation” is often used interchangeably with “preservation” when it comes to matters pertaining to urban planning. However, these terms can hold different meanings.

Preservation can be seen as a narrower concept involving physical work carried out or guidelines drawn up to ensure that a property of cultural value is preserved for posterity. Supported by research and education, preservation work includes the examination, documentation, treatment and preventative care of a property.

In Singapore, the Preservation of Sites and Monuments is the national authority that advises on the preservation of nationally significant monuments and sites. It is guided by the Preservation of Monuments Act that provides “for the preservation and protection of National Monuments”.

Conservation, on the other hand, is a much broader concept. Instead of perceiving a property as an individual entity, its historical and cultural value is considered in tandem with the surrounding built environment. Conservation can be applied to buildings (individually or in clusters), localities (streets, blocks, environments or precincts) and even special gardens or landscapes. In other words, conservation does not just focus on the physical aspects of the structures that are worth preserving, but also the stories behind them.

Heritage Sites Identified in Postwar Singapore

| Committee for the Preservation of Historic Sites and Antiquities (1954) | Singapore Improvement Trust (1958) |

| 1 Raffles Institution* | 1 Raffles Institution* |

| 2 H.C. Caldwell’s House* | 2 H.C. Caldwell’s House* |

| 3 Cathedral of the Good Shepherd* | 3 Cathedral of the Good Shepherd* |

| 4 St Andrew’s Cathedral* | 4 St Andrew’s Cathedral* |

| 5 Victoria Theatre* | 5 Victoria Theatre* |

| 6 Tanah Kubor Temenggong, Telok Blangah* | 6 Tanah Kubor Temenggong, Telok Blangah* |

| 7 Church of St Gregory the Illuminator (Armenian)* | 7 Church of St Gregory the Illuminator (Armenian)* |

| 8 3 Coleman Street (Coleman House)* | 8 3 Coleman Street (Coleman House)* |

| 9 Hokkien Temple, Telok Ayer Street* | 9 Hokkien Temple, Telok Ayer Street* |

| 10 Teochew Temple, Phillip Street* | 10 Teochew Temple, Phillip Street* |

| 11 Silat Road Temple* | 11 Silat Road Temple* |

| 12 Tua Pek Kong Temple, Palmer Road* | 12 Tua Pek Kong Temple, Palmer Road* |

| 13 Hajjah Fatimah Mosque, Java Road* | 13 Hajjah Fatimah Mosque, Java Road* |

| 14 Keramat Habib Nor, Tanjong Malang* | 14 Keramat Habib Nor, Tanjong Malang* |

| 15 Chulia Mosque, South Bridge Road* | 15 Chulia Mosque, South Bridge Road* |

| 16 Chulia Mosque, corner of Telok Ayer Street and Boon Tat Street* | 16 Chulia Mosque, corner of Telok Ayer Street and Boon Tat Street* |

| 17 Sri Mariamman Temple, South Bridge Road* | 17 Sri Mariamman Temple, South Bridge Road* |

| 18 Sri Sivam Temple, Orchard Road* | 18 Sri Sivam Temple, Orchard Road* |

| 19 Keramat Iskandar Shah, Fort Canning* | 19 Keramat Iskandar Shah, Fort Canning* |

| 20 Corner of Ellenborough Building* | 20 Corner of Ellenborough Building* |

| 21 Gateways of Fort Canning Cemetery* | 21 Gateways of Fort Canning Cemetery* |

| 22 Chettiar Temple, Tank Road* | 22 Chettiar Temple, Tank Road* |

| 23 Elgin Bridge | 23 Outram Gaol |

| 24 Buddhist Temple, Kim Keat Road | 24 Killiney House (3 Oxley Rise/Belle Vue House) |

| 25 Tan Seng Haw, Magazine Road | 25 Geok Hong Tian Temple, Havelock Road |

| 26 Ying Fo Fui Kun, Telok Ayer Street | 26 Indian Temple in Kreta Ayer |

| 27 Ning Yueng Wui Kuan, South Bridge Road | 27 Arab Street Keramat |

| 28 Benggali Mosque, Bencoolen Street | 28 Sultan’s Gate House (or Istana Kampong Glam) |

| 29 Assembly House (Old Parliament House) | 29 Cemetery, Kampong Radin Mas |

| 30 Yeo Kim Swee’s Godown, North Boat Quay | 30 Indian cemetery off Lorong 3, Geylang |

| 31 Sun Yat Sen Villa | |

| 32 Sri Perumal Temple, 397 Serangoon Road | |

| * indicates a site that is common to both lists. |

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013); Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He is also a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013); Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He is also a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.

NOTES

-

Old graves examined. (1950, October 20). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Plans to preserve & beautify old cemetery at Fort Canning. (1951, October 17). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tombstones to go into wall – At Garden of Memory. (1954, May 21). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Plan to preserve all historical buildings. (1954, November 4). Singapore Standard, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Gibson-Hill, G. A. (1954, October 29). Plaques on old buildings. In Ancient Monuments Committee, 625/54. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore. (Microfilm no.: PRO 14). ↩

-

See text box for the list of historic sites identified by the committee. ↩

-

Singapore Standard, 4 Nov 1954, p. 4. ↩

-

Colony of Singapore. (1955). Master Plan: Written statement (p. 17). Singapore: Govt. Print. Off. (Call no.: RCLOS 711.4095957 SIN). ↩

-

Untitled memorandum. (1963, May 30). In Ancient monuments and lands and buildings of historic architectural interests:Committee to re-examine the list of 32 items, 276/63. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore. (Microfilm no.: AR66). ↩

-

Minutes of the 1st meeting of Committee on Ancient Monuments and Lands and Buildings of Architectural and/or Historic Interest. (1963, August 26). In Ancient monuments and lands and buildings of historic architectural interests: Committee to re-examine the list of 32 items, 276/63. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore. (Microfilm no.: AR66). ↩

-

Colony of Singapore. (1958). Master Plan: Written statement (p. 31). Singapore: Govt. Print. Off. (Call no.: RCLOS 711.4095957 SIN). ↩

-

Friends of Singapore. (1938). Charter of the Friends of Singapore (p. 1). Singapore: Friends of Singapore. (Microfilm no.: NL11216); Opening of new chapter in history of Singapore. (1937, July 9). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Another park and museum for S’pore? (1955, November 9). Singapore Standard, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Friends of Singapore. (1958). The house in Coleman Street (p. 1). Singapore: Straits Times Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 728 FRI). ↩

-

Marina Hill ‘battle’ is over. (1956, July 12). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ong, T. W. (1957, August 8). Combine beauty with utility. The Straits Times, p. 6; Scenery to draw the tourist. (1957, July 15). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

This house with a past has an uncertain future. (1956, June 21). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kong, L., & Yeoh, B.S.A. (1994, March). Urban conservation in Singapore: A survey of state policies and popular attitudes. Urban Studies, 31 (2), 247–265, p. 248. (Call no.: RART 307.1205 US). ↩

-

Teh, C.W. (1975). Public housing in Singapore: An overview. In S.H.K Yeh (Ed.), Public housing in Singapore: A multidisciplinary study (pp. 5–6). Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 363.5095957 PUB); Choe, A.F.C. (1975). Urban renewal. In S.H.K Yeh (Ed.), Public housing in Singapore: A multidisciplinary study (pp 97–98). Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 363.5095957 PUB). ↩

-

Housing and Development Board. (1966). Annual report 1965 (p. 84). Singapore: Housing Development Board. (Call no.: RCLOS 711.4095957 SIN). ↩

-

Lorange, E. (1962). Final report on central area redevelopment of Singapore City (p. 33). Singapore: Govt. Print. Off. (Not in NLB holdings). ↩

-

Abrams, C. et. al. (1963). Growth and urban renewal in Singapore (paras. 5.21–5.24). Singapore: Govt. Print. Off. (Not in NLB holdings). ↩

-

Singapore Planning and Urban Research Group. (1967). SPUR 1967 (p. 21). Singapore: Singapore Planning and Urban Research Group. (Call no.: RCLOS 307.1216095957 SIN). ↩

-

Choe, A.F.C. (1975). Urban renewal. In J. B. Ooi & H. D. Chiang (Eds.). Modern Singapore (pp. 165–166) Singapore: University of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 OOI). ↩

-

Untitled letter. (1967, June 3). In Preservation of building of architectural or historic interest, 254/67. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore. (Microfilm no.: AR82). ↩

-

See Blackburn, K., & Tan, P.H.A. (2015, August). The emergence of heritage conservation in Singapore and the Preservation of Monuments Board (1958–76). Southeast Asian Studies, 4 (2), 341–364. (Call no.: RSEA 959.005 SASKJS). ↩

-

Minutes of the 1st meeting of Committee on Ancient Monuments and Lands and Buildings of Architectural and/or Historic Interest, 26 Aug 1963. ↩

-

Report of Sub-Committee on Preservation of Buildings and Sites of Architectural or Historic Interest. (1967, September 21). In Ancient monuments and lands and buildings of historic architectural interests: Committee to re-examine the list of 32 items, 276/63. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore. (Microfilm no.: AR66). ↩

-

Minutes of 3rd Committee on Ancient Monuments and Lands and Buildings of Architectural and/or Historic Interest. (1964, March 17). In Ancient monuments and lands and buildings of historic architectural interests: Committee to re-examine the list of 32 items, 276/63. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore. (Microfilm no.: AR66). ↩

-

Report of Sub-Committee on Preservation of Buildings and Sites of Architectural or Historic Interest, 21 Sep 1967. ↩

-

Minutes of 3rd Committee on Ancient Monuments and Lands and Buildings of Architectural and/or Historic Interest, 17 Mar 1964. ↩

-

Report of Sub-Committee on Preservation of Buildings and Sites of Architectural or Historic Interest, 21 Sep 1967. ↩

-

Campbell, W. (1969, February 7). Singapore plans to save its history. The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Republic of Singapore. Government Gazette. Acts Supplement (pp. 481–490). (1970, December 11). The Preservation of Monuments Act 1970 (Act 45 of 1971). Singapore: Govt. Print. Off. (Call no.: RSING 348.5957 SGGAS); Republic of Singapore. Government Gazette. Subsidiary Legislation Supplement (p. 380). (1971, January 29). The Preservation of Monuments Act (Commencement) Notification (S 29/1971). Singapore: Govt. Print. Off. (Call no.: RSING 348.5957 SGGSLS). ↩

-

Preservation of Monuments Board. (1979). Report for the period 1975 to August 1978 (p. 7). Singapore: Preservation of Monuments Board. (Call no.: RCLOS 722.4095957 PMBSR). ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority. (1978). Annual report 1976/77 (p. 31). Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority. (Call no.: RCLOS 354.5957091 URASAR). ↩

-

Oon, V. (1977, December 9). A gourmet walk down Food Alley. New Nation, pp. 12–13; Wong, A. K. (1985, January 25). How the Cuppage Road area was reborn. The Straits Times, p. 12; Finance Minister to open STB’s Tudor Court. (1970, October 22). Singapore Herald, p. 13; Westerhout, D. (1985, May 26). Peranakan Place: Some love it, others don’t. Singapore Monitor, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Aleshire, I. (1986, December 27). 6 areas to be preserved. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Urban Redevelopment Authority. (1988). Annual report 1986–87 (pp. 11–13). Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority. (Call no.: RCLOS 354.5957091 URASAR); Kong, L. (2011). Conserving the past, creating the future: Urban heritage in Singapore (pp. 40–41). Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority. (Call no. RSING 363.69095957 KON). ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority. (1986). Conserving our remarkable past (pp. 1–2). Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.57 CON). ↩

-

Kong & Yeoh, Mar 1994, p. 250. ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority. (2009). No. 9 Neil Street: Revitalisation of Tanjong Pagar. Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority. Retrieved from Urban Redevelopment Authority website. ↩

-

Republic of Singapore. Government Gazette. Acts Supplement. (1989, August 25). Planning (Amendment No. 2) Act 1989 (Act 31 of 1989). Retrieved from Singapore Statues Online website. ↩

-

National Heritage Board. (n.d.). Preservation of Sites and Monuments. Retrieved from National Heritage Board website. ↩

-

National Heritage Board. (n.d.). Historic sites. Retrieved from National Heritage Board website. ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority. (n.d.). Brief history of conservation. Retrieved from the Urban Redevelopment Authority website. ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority. (2017). Conservation guidelines. Retrieved from Urban Redevelopment Authority website. ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority. (n.d.). Architectural Heritage Awards. Retrieved from Urban Redevelopment Authority website. ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority. (n.d.). Architectural Heritage Season. Retrieved from Urban Redevelopment Authority website; Ministry of National Development. (2017, October 31). Speech by 2M Desmond Lee at the URA Architectural Heritage Awards 2017. Retrieved from Ministry of National Development website. ↩