The Story of Two Shipyards: Keppel & Sembawang

Keppel and Sembawang shipyards are major players in Singapore’s maritime and shipping industry. Wee Beng Geok traces the colonial origins of these two companies.

Singapore has always been highly prized for its location. Fortuitously positioned at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, at a key crossroad along the East-West trade route, its importance as a port settlement can be traced to the 14th century when the island was known as Temasek.

In 1819, the British arrived on the scene, and were quick to grasp Singapore’s potential as an entrepôt and a base to spread its version of merchant capitalism in Southeast Asia. Land was leased from the indigenous rulers to set up a British trading post on the island, and in a treaty signed in 1824, Singapore was ceded in full to Britain. For the next 140 years, the British built institutions that would lay the foundations for the rise of a modern global city, including a market infrastructure that took advantage of Singapore’s strategic position as a prime node in the global shipping routes.

Two dockyard entities from the colonial period became precursors of well-known post-independence companies: Keppel Shipyard and Sembawang Shipyard. Although the origins and legacies of these two shipyards could not be more different, their trajectories were shaped by the imperatives of the British Empire as well as an industrialising Britain that was at the forefront of major technological and business innovations. One shipyard had purely commercial roots, while the other was a military naval base established to protect British imperial interests in Asia.

Early Dockyard Entrepreneurs

The advent of steamships for sea transportation in the 19th century drew entrepreneurs to invest in the ship repair business in Singapore. Although steamships were faster and more reliable compared with wind-powered vessels, repairs to the steamship hull – unlike sailing vessels – could not be done by beaching the vessel1 but had to be carried out in a drydock.2

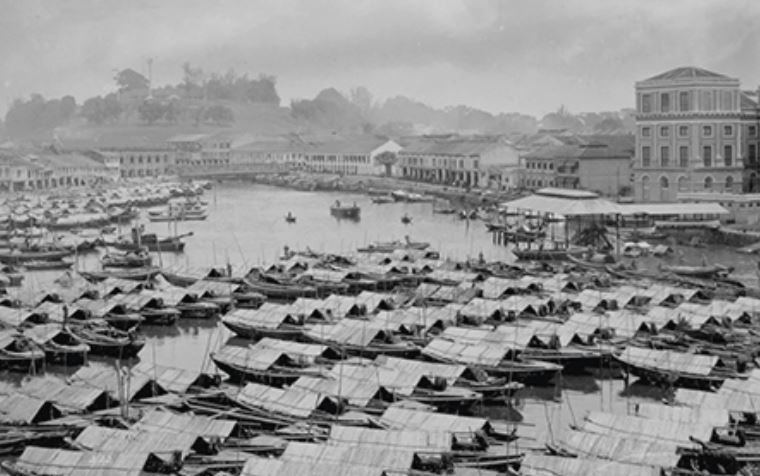

The use of steamships also required new logistical arrangements. Coal, the energy source of steamships, had to be first transferred from coal-carrying ships anchored at the mouth of the Singapore River onto small lighters, which in turn transported the coal to warehouses situated along the river bank for storage. Lighters then transported the coal out to the arriving steamships. It was a laborious process, made all the worse during stormy weather and choppy seas when the lighters would sometimes capsize, resulting in tons of lost coal. Furthermore, stored damp coal combusted easily and became a constant fire hazard.

In 1845, the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O) in London began monthly sailings to the Far East, including a stop in Singapore. In 1852, P&O became the first shipping company to move its coaling stations from the Singapore River to New Harbour (now Keppel Harbour3) where it built its own wharf. The new location had a sheltered anchorage, a pier for bunkering, as well as space for coal storage and godowns (warehouses). Other shipping firms followed suit and New Harbour, with its deep waters, soon became the preferred berthing location for ships calling at Singapore.

With increased steamship traffic, several Singapore-based British and European companies as well as residents became keen to invest in the construction of drydocks for ship repair. Although considerable start-up capital was needed, the returns were projected to be good and several companies were willing to take the risk.

Competition, Monopoly and a Government Takeover

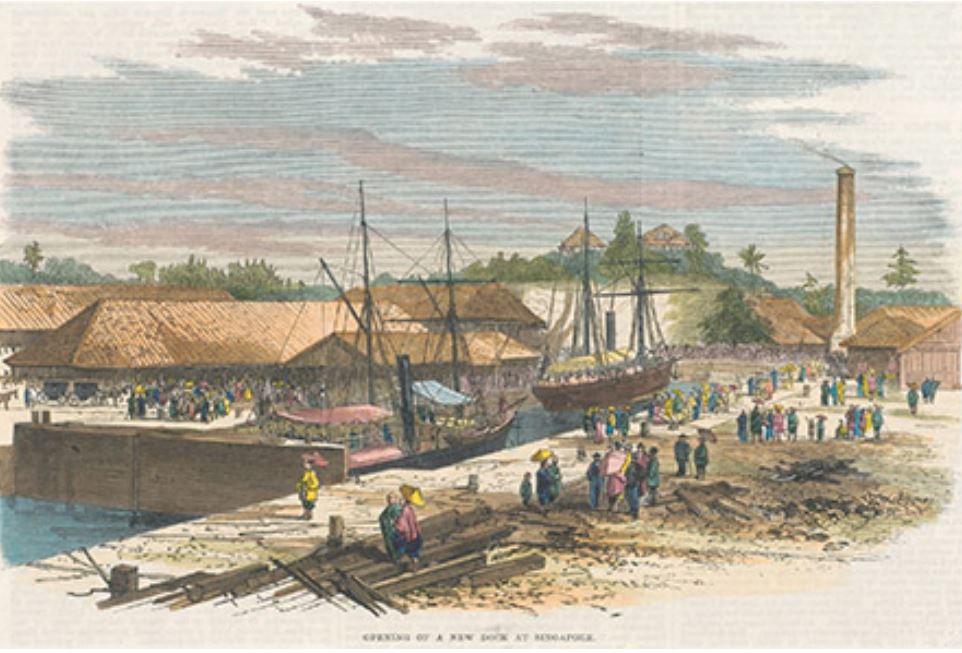

New Harbour was deemed a suitable location for drydocking facilities. In 1859, British mariner Captain William Cloughton built Singapore’s first drydock, aptly named Dock No. 1, at New Harbour. The Patent Slip and Dock Company was subsequently formed in 1861 to assume control of this ship repair facility.

In 1864, a group of investors decided to build another drydock at New Harbour. To raise funds for the project, they set up a joint-stock limited liability company – Tanjong Pagar Dock Company Limited (TPDC) – which became the first local joint-stock company to offer shares to the public in Singapore.

The TPDC initially hoped to raise $200,000 in Singapore, with 2,000 shares of $100 each available for purchase. However, as not all shares were taken up by local residents, the balance was sold to investors in London. With a reasonably attractive dividend policy, TPDC shares were considered a good investment by the 1870s. In subsequent fundraising exercises, new shares were offered for sale at a premium, with some bought by shareholders in London.

Victoria Dock, TPDC’s first drydock located on the western side of Tanjong Pagar, started operations in 1868. With the opening of this new dock, the Patent Slip and Dock Company faced intense competition. It mounted a price war, and TPDC was forced to cut its prices. Although TPDC’s drydock business faced losses as a result of this move, its wharf services still managed to turn in a profit and became the company’s main income source.

With the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, more steamships called at Singapore and, by the following year, dock operations had become profitable. In 1870, Patent built its second dock, Dock No. 2, at New Harbour. Nine years later, in 1879, TPDC built another drydock, Albert Dock, located to the east of Victoria Dock, to meet the growing demand. The TPDC began to acquire smaller rivals that owned docks and wharves at New Harbour, but who were less able to withstand the competitive business environment.

Finally, in 1899, TPDC merged with its main rival, the New Harbour Dock Company (in 1875, Patent Slip and Dock Company had incorporated itself into a public company bearing this name). With this acquisition, TPDC came to control the entire shipping, dockyard and wharf business at New Harbour, except for the P&O wharf. Singapore’s port and its future prosperity rested heavily on TPDC’s shoulders.

Singapore’s port was the seventh largest in the world in 1904 but faced strong overseas competition, especially from the port in Hong Kong. TPDC’s port facilities became increasingly inadequate to compete internationally and the company’s wharf system was under severe strain as no major improvements to its facilities had been carried out since 1885.

This situation was exacerbated by differences with regard to capital spending between the TPDC Board in Singapore and the London Consulting Committee in Britain representing the company’s group of European and British shareholders.4

In March 1904, TPDC submitted a $12-million modernisation plan to upgrade and expand its facilities, including a proposed financing scheme. This was rejected by the company’s Europe-based shareholders, who were concerned that the costs of financing the project would “endanger a dividend of 12 per cent”.5 TPDC sought financial support from the Straits Settlements government, but instead the government decided to expropriate the company’s assets and take over the management of its operations.

With the passing of the Tanjong Pagar Dock Ordinance in April 1905, TPDC became a government organisation known as the Tanjong Pagar Dock Board. TPDC shareholders received from the government $761 for each $100 share – substantially higher than the $600 peak reached by the share in the stock market. The board was reconstituted in 1913 as a statutory board known as Singapore Harbour Board (SHB). In the same year, the SHB launched King’s Dock, the largest dock east of the Suez. In 1917, another drydock, Empire Dock, was completed. Port facilities at Keppel Harbour were also enhanced.

The SHB retained TPDC’s monopolistic ship repair business, and for the next five decades, it controlled the entire chain of repair business at Keppel Harbour. With its sizeable facilities, the SHB soon edged out the smaller shipyards and engineering workshops in Tanjong Rhu and Kallang. This commanding position lulled the SHB to such complacency that by the end of the 1950s, capital investment had slowed down considerably and SHB’s costs and productivity began lagging behind overseas dockyards like Hong Kong’s.

A New Naval Base in Asia

After World War I, as the locus of naval power moved to the Pacific, the Board of Admiralty in London, as part of its appraisal of British naval policy, proposed building a new naval base facility in Asia. In the light of the growing threat posed by the Japanese military and rising international tensions, Britain grew anxious to protect its empire in Asia, and Singapore was considered the most ideal location for its new naval base.

Although British naval ships had previously docked at SHB’s drydocks, the new British battleships were too large to berth at these facilities as their anti-torpedo bulges extended out on either side of the ship’s hull. Thus, Sungei Sembawang, facing the Johor Strait, was chosen as the new site to construct the naval dockyard. Its strategic location as well as the deep waters of the Johor Strait would provide good anchorage for the naval fleet, bolstered by facilities such as onshore wharves and workshops.

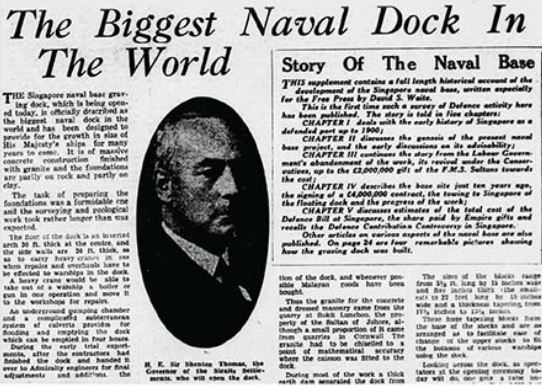

The Singapore Naval Base Scheme was announced to the British Parliament in 1923. The plan was immediately met with hostile reactions from the British public, who were weary of war and expected the government to improve their lives through more social spending. Although the original plan was for the naval dockyard in Singapore to be completed in 1930, the construction timeline was extended by another three years to avoid the immediate need for heavy expenditure. The completion date of the naval dockyard was thus pushed back to 1933.

To appease its citizens back home, Britain sought monetary contributions from its Asian colonies to ease the funding burden. In May 1923, Singapore made a gift of 2,845 acres of land for the naval base valued at about £150,000, or 1.25 million Straits dollars. This was followed by a donation of £250,000 from the Hong Kong government. Domestic issues in Britain in 1924, however, impeded progress when the incoming Labour government blocked the funds that had been earmarked for the construction of the dock. When the Conservative government returned to power in late 1924, the Singapore Naval Base Scheme was revived, but the construction of the drydock was delayed yet again.

In mid-1926, the largest single contribution of £2 million was received from the Federated Malay States. Then in April 1927, New Zealand came forward with a commitment of £1 million to be disbursed over eight years.

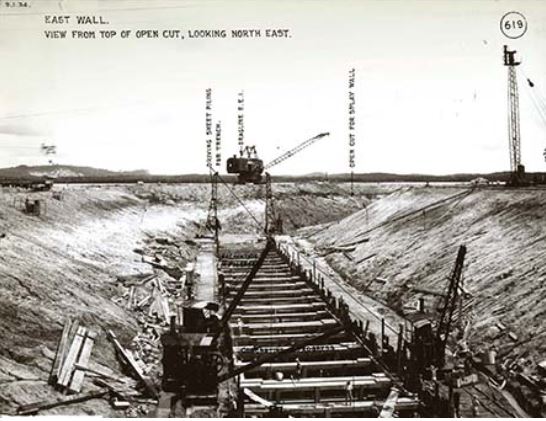

In 1928, the tender for the drydock and wharf construction in Sembawang was awarded to a South African company, Sir John Jackson’s Ltd, for £3.7 million, and construction began with some 5,000 workmen and 100 British staff. Millions of feet of soil were dug, and 1.6 million tons of granite stone were brought in from Johor. In the same year, a newly built floating dock, with lifting capacity of 50,000 tons, was commissioned at Sembawang, and a floating crane with a lifting capacity of 100 tons also arrived.

However, the building momentum almost ground to a halt when a new Labour government came into power in Britain in 1929. As the government was unable to abort the project, it decided to slow down the pace of construction.

In 1931, the Japanese army invaded Manchuria. Faced with the looming prospect of a war with Japan, the completion of Sembawang Naval Base became a priority for Britain. King George VI Dock was finally completed in early 1938 and was touted as one of the largest naval docks ever built, capable of accommodating the biggest ship in the world.

The War Comes to Singapore

In December 1941, as Japanese imperial forces advanced into Singapore from Malaya, Sembawang Naval Base came under heavy Japanese shell and mortar attack. Just before the British surrendered to the Japanese on 15 February 1942, the retreating British naval personnel blew up the drydock’s caisson and pumps as well as its electrical generating plant. The intention was to prevent the Japanese from using the naval base. The Japanese navy, however, managed to repair the damaged facilities at Sembawang Naval Base and used it to service its naval fleet during the Japanese Occupation.

As the tide of war turned in late 1944, the naval base became the target of air raids by Allied Forces, and the dockyard facilities suffered severe damage. When the British returned to Singapore following the Japanese surrender in September 1945, they began repairing and upgrading the naval base facilities. By the end of 1951, Sembawang Naval Base was back on its feet again.

The postwar years leading up to the 1960s were the most productive for the naval base. With British involvement in the Korean War in 1949 and other regional conflicts, the dockyard serviced a wide range of naval vessels in the region, including aircraft carriers, commando helicopter carriers, cruisers, destroyers, frigates, submarines and minesweepers.

Developing a Ship Repair Industry

Singapore inched closer to independence from British rule when the first Legislative Assembly general election was held in 1959. The victorious People’s Action Party which formed the government, was faced with bleak economic prospects and severe unemployment, and its key priority was the creation of jobs for a young and growing population.

In October 1960, a United Nations Industrial Survey Mission led by Dutch economist Albert Winsemius visited Singapore to conduct a feasibility study and provide advice on how to steer its fledgling economy. In the final report submitted in June 1961, the team identified ship repair and shipbuilding as a potential industry as it would take advantage of Singapore’s natural deep harbour and strategic location while providing employment to thousands. In line with this vision, one of the government’s first moves was to restructure and reorganise the ship repair operations of the SHB and Sembawang Naval Base.

A two-step process to restructure the SHB began in 1964. First, the Port of Singapore Authority (PSA) was set up as a statutory board to take over the functions, assets and liabilities of the SHB. The new entity would also manage port operations and serve as the government port regulator.

Second, SHB’s dockyards, which had more than a century of commercial ship repair experience, were restructured as a separate business entity. In September 1968, Keppel Shipyard Pte Ltd, with shareholdings held by the Singapore government, was incorporated to take over SHB’s ship repair operations. The SHB ceased to exist.

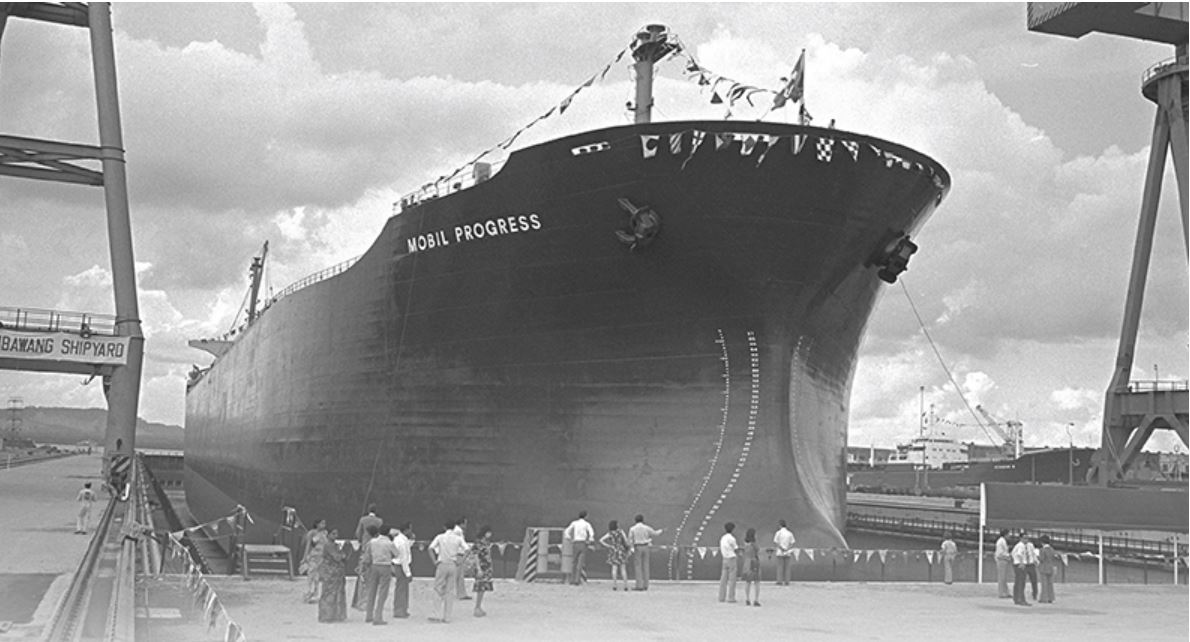

After Singapore gained independence in 1965, the British gradually reduced its military presence in the region. The formation of Sembawang Shipyard Pte Ltd in 1968 was precipitated by Britain’s surprise announcement in January that year of an early withdrawal of its military forces in Singapore, including the closure of Sembawang Naval Base, by 1971.

In June 1968, the Singapore government began the process of converting the naval base into a government-linked commercial entity known as Sembawang Shipyard Pte Ltd. The shipyard began operations in December the same year after the British government sold the naval base to Singapore for a token sum of $1. The assets of the naval base were valued at £2 million and included a 100,000-dwt drydock, five floating docks, a mile-long deepwater berthside, full cranage and 22 hectares of workshop facilities.

A New Vision for Keppel and Sembawang

In 1968, Hon Sui Sen, then Chairman of the Economic Development Board, was appointed the first chairman of both Keppel and Sembawang shipyards. His first priority was to transform the two shipyards into for-profit business enterprises. The same year, British shipbuilding group, Swan Hunter of Tyneside, England, was appointed as managing agent to help the shipyards build up their capabilities and resources. These included the development of international commercial and marketing networks that were critical for success in the ship repair business.

By then, decades of monopolistic practices had made Singapore’s ship repair business uncompetitive. The same job that took 20 days to complete in Singapore required a mere six days in Hong Kong. Furthermore, charges were generally 15 percent lower in Hong Kong compared to Singapore.

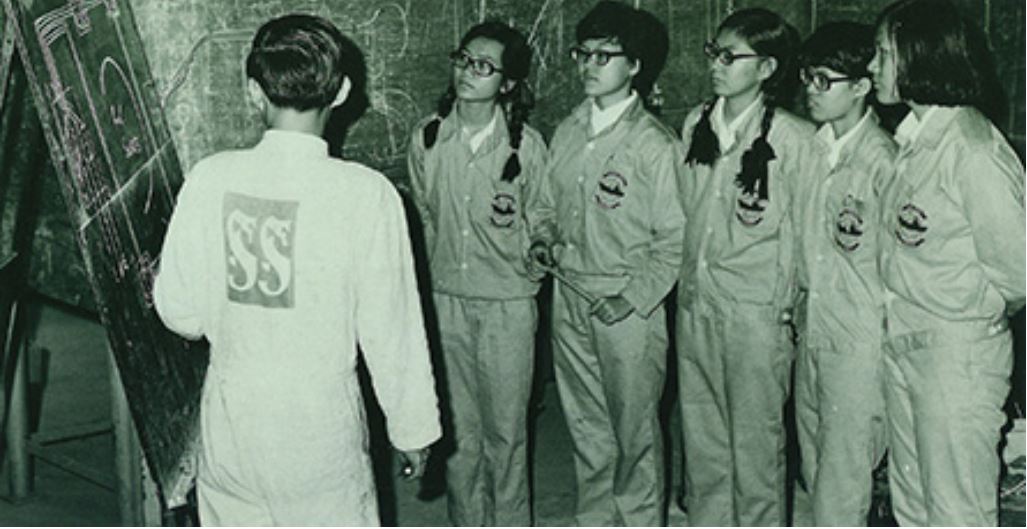

One stumbling block was caused by Sembawang’s elaborate naval dockyard design. In comparison, commercial dockyards had compact designs, making them more cost-efficient. New skillsets and business processes in areas such as international networks, marketing, commercial estimating and billings had to be developed, as these capabilities had not been the concerns of a naval dockyard. Swan Hunter’s brief included training local managers and technical staff as well as transferring essential skills and knowledge to a new generation of Singaporean shipyard engineers and managers, who would eventually take over the reins.

The two shipyards set up their own apprenticeship training centres – Keppel in 1969 and Sembawang in 1972. Many young Singaporeans who completed these apprenticeship programmes formed the backbone of Singapore’s maritime industry in the 1980s and 90s.

Keppel and Sembawang shipyards became major beneficiaries of scholarship programmes aimed at nurturing local talent to fill key positions in Singapore’s maritime and shipping industry. Recipients of various government and the Colombo Plan scholarship schemes were among the first generation of local engineers and managers at the two shipyards.

Before Swan Hunter’s managing contract with Keppel ended in 1972, a group of Keppel’s key local officers drafted a localisation plan and submitted the blueprint to the chairman of the board. The blueprint was accepted and a local management team took over the shipyard on 1 June 1972, helmed by its new chairman, a prominent Eurasian named George Bogaars. Chua Chor Teck, a former naval dockyard apprentice and naval architecture graduate, was appointed general manager. Briton C.N. Watson of Swan Hunter was retained as interim managing director until 1974, when Chua took over.

Keppel’s new management built a 150,000-dwt drydock on reclaimed land in Tuas, and the new yard commenced business in June 1977 when the dock was completed. In 1979, work on another drydock for ultra-large crude carriers of up to 330,000 dwt began at the Tuas shipyard.

In 1980, Keppel Shipyard Limited (KSL) shares were listed and traded on the Stock Exchange of Singapore, with the launch of an initial public offering of 30 million shares at $3.30 each. Besides the Singapore government, KSL shareholders included institutional investors and private individuals.

Swan Hunter’s contract with Sembawang Shipyard was for 10 years beginning from 1968: the first three years to commercialise the naval dockyard and the subsequent seven years to transform it to a full-fledged ship repair enterprise.

In 1970, senior civil servant Pang Tee Pow was appointed the board chairman of Sembawang Shipyard and Lim Cheng Pah, also from the public service, became its first local senior manager. As the director of personnel and training, Lim led the localisation initiative to nurture and train local staff. In 1972, the year that Sembawang first began commercial operations, the company achieved a revenue of $71.2 million, with a profit of $15 million. This positive start gave Sembawang the confidence to seek public funds through an initial public offering on the Singapore Stock Exchange in June 1973. The company raised $51 million through the issue of 25 million shares at $2.04 each. In 1975, a new and larger drydock catering to the repair market for very large crude carriers was completed.

By the time Swan Hunter personnel left in 1978, almost all the managers in Sembawang were Singaporeans, except for the managing director C.N. Watson, who had previously been with Keppel. Lim succeeded Watson as managing director in 1983, thus completing the entire localisation process.

Over the next three decades, Keppel and Sembawang would emerge as major players in Singapore’s maritime and shipping industry as well as leaders in the global offshore rig construction business.

Today, Keppel Shipyard is a division of Keppel Offshore & Marine, one of the core businesses of conglomerate Keppel Corporation. Keppel Shipyard has three yards in Singapore – Tuas, Benoi and Gul – which together operate five drydocks.

Sembawang Shipyard was renamed Sembcorp Marine Admiralty Yard in 2015. Today, it has five docks, the largest being the 400,000-dwt Premier Dock, as well as KG VI Dock, which is one of the deepest in Southeast Asia. Admiralty Yard is one of the four major yards in Singapore operated by Sembcorp Marine Limited.

The dockyards were not spared the highly politicised labour movement that swept through Singapore in the 1950s and 60s. On 30 April 1955, around 1,300 port workers employed by the Singapore Harbour Board (SHB) Staff Association went on strike for better wages and working conditions. In June, the strike found greater support when unions representing 40,000 workers in Singapore threatened to join their shipyard counterparts.

The strike ended on 6 July after an agreement was reached between the association and the SHB management. According to one estimate, the protracted negotiations over the three-month period took up nearly 100 hours, with the SHB forking out at least $500,000 a year as a result of the wage increases it offered to the striking workers.

The government became concerned that labour activism could derail its efforts to commercialise the dockyards. With the incorporation of Keppel and Sembawang shipyards as business entities in 1968, house unions were set up to represent employees of each shipyard, with the hope of aligning the union’s objectives with that of the new business enterprise.

Dr Wee Beng Geok is a former Associate Professor of Strategy and Management at Nanyang Technological University. In 2000, she set up the Asian Business Case Centre, Nanyang Business School, and was its director for 15 years. She has also worked in the corporate sector, including more than a decade in Singapore’s marine industry.

Dr Wee Beng Geok is a former Associate Professor of Strategy and Management at Nanyang Technological University. In 2000, she set up the Asian Business Case Centre, Nanyang Business School, and was its director for 15 years. She has also worked in the corporate sector, including more than a decade in Singapore’s marine industry.

REFERENCES

Chew, M. (1998). Of hearts and minds: The story of Sembawang Shipyard. Singapore: Sembawang Shipyard Limited. (Call no.: RSING 623.83 CHE).

Keppel Shipyard Limited. (1980, October 27). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG

Lim, R. (1993). Tough men, bold visions: The story of Keppel. Singapore: Keppel Corporation Limited. (Call no.: RSING q338.762383095957 LIM).

McIntyre, W.D. (1979). The rise and fall of the Singapore Naval Base 1919–1942. London: MacMillan. (Call no.: RSING 359.7 MAC).

National Library Board. (2014). Formation of the Port of Singapore Authority. Retrieved from HistorySG.

Neidpath, J. (1981). The Singapore Naval Base and the defence of the Britain’s eastern empire, 1919–1941. Oxford; New York: Clarendon Press. (Call no.: RSING 359.7 NEI).

Turnbull, C.M. (1989). A history of Singapore: 1819–1988 [2nd ed.]. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS]).

NOTES

-

“Beaching” refers to the act of laying the vessel on its side on a beach to conduct hull repair and maintenance work. ↩

-

A drydock is a large dock from which water can be pumped out, and is used for repairing a ship below its waterline. Also sometimes referred to as a “graving dock”. ↩

-

New Harbour was renamed Keppel Harbour in 1900 after Admiral Henry Keppel, who five decades earlier, in 1848, had sailed the naval ship HMS Meander into New Harbour for repair and was astonished to find deep water so close to the shore. He reported to the Board of Admiralty in London and then to the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company on the discovery of this deep harbour for steamships and its potential as a port. ↩

-

TPDC’s Articles of Association gave veto rights to the London Consulting Committee (which functioned more like a London Board) for expenditures beyond $20,000. See Bogaars, G. (1956). The Tanjong Pagar Dock Company, 1864–1905 (p. 171). Singapore: Govt. Print. Off. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.51 BOG). ↩