Don’t Mention the Corpses: The Erasure of Violence in Colonial Writings on Southeast Asia

History may be written by the victors, but what they conveniently leave out can be more telling. Farish Noor reminds us of the violent side of colonial conquest.

“All conquest literature seeks to explain to the conquerors ‘why we are here’ d.”1

Among the many outcomes of the colonial era in Southeast Asia – from the 18th to the 19th century – is a body of writing that can be best described as colonial literature. By this I am referring not only to the accounts that were written by intrepid European travellers who ventured to this region, but also the writings of colonial bureaucrats, colony-builders and administrators, and the men who took part in the conquest of the region by force of arms.

The Justification for Violence

It is interesting to see how these authors dealt with the issue of violence that often came with colonisation, and how such violence was sometimes justified or even celebrated. In the long-drawn process of colonisation in Burma, Anglo-Burmese relations were largely hostile throughout most of the 19th century, and culminated in a series of costly wars: the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–26), the Second Anglo-Burmese War (1852–53) and the Third Anglo-Burmese War (7–29 November 1885).

Among those who wrote about these wars was Major John J. Snodgrass, whose account of the First Anglo-Burmese War was from the viewpoint of a British officer serving in the colonial army. Snodgrass’ Narrative of the Burmese War (1827) was a work that was bellicose and ultimately triumphalist in tone and tenor, and as he had conceded earlier in his work, the war was in fact “an unequal contest”.2 Although Snodgrass had little sympathy for the Burmese as a people – his work is full of snide and disparaging remarks about the Burmans and their ruler – he did not hide the fact that the battles of the First Anglo-Burmese War were ferocious, and remarked that “our first encounters with the troops of Ava were sanguinary and revolting”.3

A similar kind of frankness can be found in the works of men like Admiral Henry Keppel, George Rodney Mundy and Frank Marryat. All three were navy men, and all of them had taken part in the naval campaign off the coast of Sarawak that led to the eventual attack on the Kingdom of Brunei. The works of these three men – Keppel’s Expedition to Borneo of HMS Dido for the Suppression of Piracy (1846);4 Mundy’s account in Narrative of Events in Borneo and Celebes, Down to the Occupation of Labuan (1848);5 and Marryat’s Borneo and the Indian Archipelago (1848)6 – would become the most widely read accounts of the so-called “war on piracy” in maritime Southeast Asia, ultimately adding the seal of legitimacy for what was really a sustained campaign to weaken Brunei’s standing as an independent Southeast Asian polity.

Although Keppel, Mundy and Marryat were directly involved in the naval campaign in Borneo, and supportive of the efforts to expand British colonial power across the region while weakening the power of local kingdoms such as Brunei, they were also brutally frank in their accounts of the conflict and the realities of colonial warfare.

Keppel and Mundy did not hide the fact that attacks on native settlements did indeed take place, and Keppel was honest enough to admit that, in the course of the subjugation of the natives of Sarawak, the colonial forces – led by the adventurer James Brooke – had also committed acts of plunder and looting.7 Keppel went as far as stating that such excessive use of violence – which included the razing of native villages to the ground – was necessary, for “without a continued and determined series of operations of this sort, it is my conviction that even the most sanguinary and fatal onslaughts will achieve nothing beyond a present and temporary good”.8

Violence was thus a constant leitmotif in many of the works written by colonial authors who arrived in Southeast Asia in the 19th century. Colonies were rarely built by peaceful negotiations, and often through the unequal contest of arms between unequal powers. In the writings of men like Snodgrass, Keppel, Mundy and Marryat, we see the power differentials between East and West laid bare as we witness the bloody genesis of new colonies across the region.

The fact that these authors did not feel the need to hide the truth that colonialism was built through violence is also a reflection of the mores and sensibilities during the age of Empire. In the 19th century, the technological gap between East and West widened. In tandem with this development arose a body of pseudo-scientific theories of racial difference and racial hierarchies in which Asians and Africans were cast as “inferior” races who were backward, degenerate and unable to govern themselves.

Such notions – though largely discredited today – were all the rage then, and were often used to justify the use of force in the process of empire-building. The idea was that “savage” and “primitive” Asians and Africans stood to benefit from exposure to Western civilisation, and would only submit to their colonial subjugators if they were forced to do so at gunpoint.

The Erasure of Violence

And yet there is also another parallel tradition of colonial writing that emerged in the 19th century. This took the form of works that seemed to deliberately sideline the topic of violence altogether, attempting to erase all memory of the violent encounters between the colonising powers and the societies they came to dominate.

Among the books written about colonial Southeast Asia where we see a near-total erasure of the memory of conflict, three works come to mind: Stamford Raffles’ The History of Java (1817),9 Hugh Low’s Sarawak: Its Inhabitants and Productions (1848)10 and Spenser St John’s Life in the Forests of the Far East (1862).11

The History of Java was a monumental two-volume work that courted controversy almost as soon as it came off the press. Raffles’ peers, such as John Crawfurd, took exception to the work and accused the author of misinterpreting elements of Javanese history by presenting a one-sided view of the Javanese as a “degenerate” race that was lost in the past and unable to progress without Western intervention. To make things worse, contemporary scholars such as Peter Carey (1992) have noted several instances of plagiarism and fabrication in Raffles’ work.12

Notwithstanding the academic shortcomings of The History of Java, there is also a glaring omission in the text – the elephant in the room as it were – which is the absence of any mention of the invasion of Java itself. In Carey’s account of the British occupation of Java from 1811 to 1816, we find a detailed recounting of the violence of the British attack as well as instances of violence, humiliation and plunder that took place during the British occupation thereafter.

The same cannot be said of Raffles’s work. Although Raffles had claimed that he had amassed more information about Java than any other European in his time, The History of Java does not elaborate on how all that data was collected and how the treasure horde of Javanese antiquities – including statuary, manuscripts, royal regalia and jewellery, among other items – was put together by Raffles for his own research and his private collection.

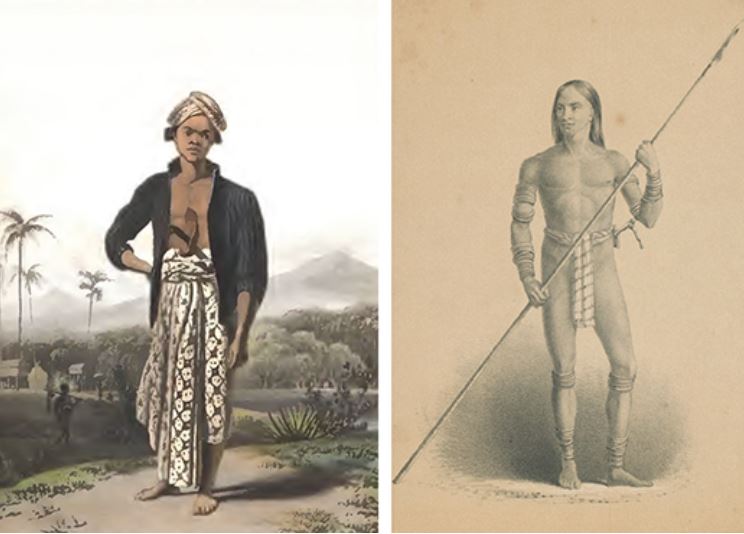

(Right) A Loondoo Dayak of Borneo, whom Frank Marryat described as being “copper-coloured, and extremely ugly: their hair jet black, very long, and falling down to the back; eyes were also black, and deeply sunk in the head, giving a vindictive appearance to the countenance; nose flattened; mouth very large; the lips of a bright vermilion, from the chewing of betel-nut; and, to add to their ugliness, their teeth black, and filed to sharp points”. Image reproduced from Marryat, F.S. (1848). Borneo and the Indian Archipelago: With Drawings of Costume and Scenery (facing p. 5). London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. Retrieved from BookSG.

The Violence Wrought Upon Java

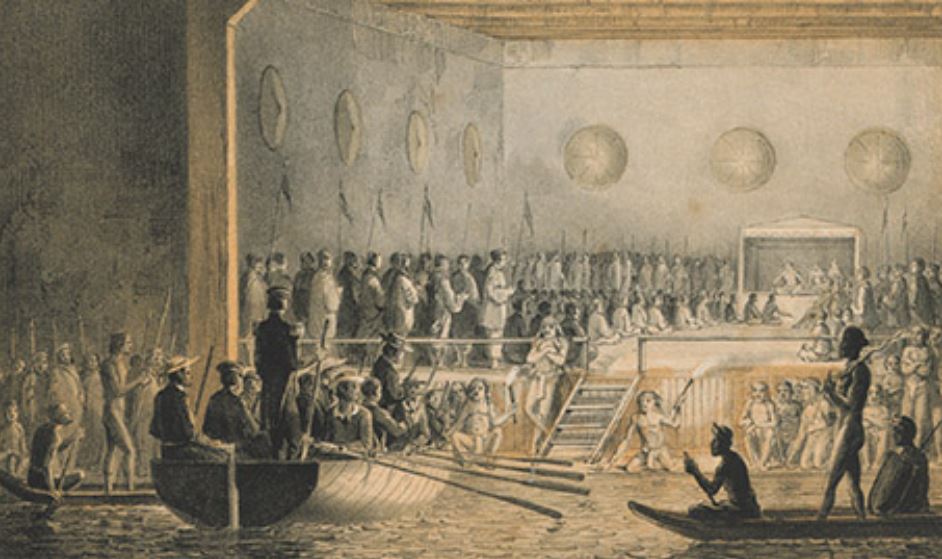

Contemporary historians have pointed out that the arrival of the British in Java, which began with the attack on Batavia (present-day Jakarta), was anything but peaceful: so violent was the assault on the fortified port-city that bodies were said to have been piled up one on top of the other. Equally shocking are local accounts of the British attack on the royal city of Jogjakarta, which led to the killing of hundreds, including the Javanese defenders who had taken cover in the royal mosque.

Carey, Tim Hannigan (2012)13 and others have noted that, in the wake of the successful attack, the Javanese royal family and nobles were forced to submit to the conquerors in the most humiliating manner, and that the royal palace was looted and sacked. Hannigan described the manner in which the Sultan of Jogjakarta was stripped of his courtly regalia by the victorious British troops, and then thrown into a backroom, “while the sepoys and English soldiers embarked on a victorious rampage” within the compound of the royal palace they had overrun.14 There are also accounts of how members of the royal family had their jewels literally ripped off their bodies by the troops of the East India Company.

And yet nowhere in The History of Java do we read of what truly happened during these assaults, and the image of Java that we are left with is that of a tranquil land rendered static and domesticated by colonial intervention. Even in the images that accompany the text – the now-famous images of Javanese monuments and the hand-coloured figure studies of the Javanese themselves – all we get to see are idyllic portraits of a land and a people rendered passive, inert and thus exposed to the outsider’s gaze.

The White Rajah who “Saved” Sarawak

Southeast Asia would experience a succession of such violent incursions where brutalities would either be subsequently erased or forgotten. More than two decades after the British occupation of Java, another military-naval campaign visited maritime Southeast Asia – the aforementioned “war on piracy” – leading to the capture of Sarawak by the former East India Company-man-turned-rogue-adventurer, James Brooke.

As noted earlier, there exist several accounts of the Sarawak campaign that were explicit in their treatment of colonial warfare. But parallel to these works was another kind of historical recounting written by the likes of Hugh Low. His book Sarawak: Its Inhabitants and Productions is startling in how it weaves a narrative that re-presents the conquest of Sarawak and the attack on Brunei in an almost fairytale-like manner.

Low’s work purported to be a study of the land and people of Sarawak as well as a history of that part of Southeast Asia. But in the course of recounting this history, Low was also attempting to present a sanitised account of how an Englishman like James Brooke could have assumed the role and title of the “White Rajah” of Sarawak. Low’s retelling of the Brooke tale borders on the fantastical when he glibly states that Rajah Muda Hassim of Sarawak found himself “tired of Sarawak”15 for no explicable reason, after which he promptly handed over the territory of Sarawak to Brooke on 24 September 1841.

What is totally absent from Low’s rose-tinted account of Brooke’s rise to prominence is the fact that Brooke, as the leader of his private army of 200 men, had attacked Rajah Muda Hassim’s compound and forced the latter to surrender to him – a fact that was highlighted in the work by Gareth Knapman (2017).16 As far as fairytale heroes go, Low’s depiction of Brooke fits the bill in many ways: for Low, nothing of significance could be achieved in Brooke’s absence or without Brooke’s guidance; Asiatic monarchs would incredulously surrender their ancestral lands to him in return for nothing; and the man was motivated by only the best motives “to do good, to excite interest and to make friends”.17

Such sanitised colonial propaganda would become the norm in the decades to come. In 1862, yet another hagiographic account of the Brooke legend appeared in the form of Spenser St John’s two-volume work, Life in the Forests of the Far East. In this work, St John repeated the familiar trope of Brooke as the white saviour whose presence alone would restore order – which was in turn framed in bold relief against a backdrop of “savage” Bornean natives and “treacherous” Bruneians and Chinese. That Sarawak’s story could only have a fairytale ending seems obvious when we consider that the story was told in conjunction with other tales of the Empire.

In order for the story of benevolent imperial intervention to make sense, it was necessary to have as its counterpart the story of native malevolence and decline; and more perceptive readers of the works of Low and St John will be able to see that both writers have woven a number of complex narratives that developed in tandem with one another.

At the forefront is, of course, the tale of the Brooke dynasty, whose messy and bloody genesis was cleaned up and sanitised. Parallel to this are three other narratives that framed Brooke’s idealised image in bold relief: the story of the decline of Malay power, embodied by the tale of Brunei’s fall from grace; the story of Chinese treachery, encapsulated in St. John’s account of the Sarawak uprising; and the story of native backwardness and vulnerability that is found in the studies of native life and customs carried out by Low and St John.

Coming to Terms with Reality

Reading works such as these today we are reminded of the fact that colonialism was a complex process that in turn gave birth to complex accounts of it. At face value, the works of Raffles, Low and St John strike the contemporary reader as being straightforward examples of colonial propaganda, which they undoubtedly were – and this was a type of writing that continued well into the 20th century, as exemplified by the works of later colonial functionaries such as Frank Swettenham (1907).18

But what is equally important to note is how and why some of these colonial writers chose to sideline or even silence the violence that invariably accompanied colonisation, and what they hoped to achieve by doing so in their writings. Scholars of colonial history are no doubt appreciative of the fact that some of these colonial-era writers – such as Snodgrass, Keppel, Mundy and Marryat – were honest in their accounts of the violence they perpetrated. At the very least, this opens the way for a critical discussion of colonialism and its enduring legacy.

The works of Raffles, Low and St John, however, pose a far greater challenge. In rereading the works of this other group of writers with a critical eye today, we see the stark and enormous gaps and long instances of silence where the brutal realities of colonial conquest were deliberately erased and eventually forgotten. In doing so, we can critique these authors for their moral complicity in what was, in the final analysis, one of the most violent eras in recent Southeast Asian history.

Dr Farish A. Noor is presently Associate Professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies and the School of History, College of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University. His latest book is Before the Pivot: America’s Encounters with Southeast Asia 1800–1900 (Amsterdam University Press, 2018).

Dr Farish A. Noor is presently Associate Professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies and the School of History, College of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University. His latest book is Before the Pivot: America’s Encounters with Southeast Asia 1800–1900 (Amsterdam University Press, 2018).

NOTES

-

Bartlett, R. (1993). The making of Europe: Conquest, colonization and cultural change, 950–1350 (p. 96). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Call no.: 940.1 BAR). ↩

-

Snodgrass, J.J. (1827). Narrative of the Burmese war […] (p. 6). London: J. Murray. (Microfilm no.: NL5084). ↩

-

Snodgrass, 1827, p. 31. ↩

-

Keppel, H. (1846). The expedition to Borneo of HMS Dido for the suppression of piracy […](vol. I and vol. II; 2nd ed.). London: Chapman and Hall. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Brooke, J., & Mundy, G.R. (1848). Narrative of events in Borneo and Celebes, down to the occupation of Labuan […] (Vol. II; 2nd ed.). London: John Murray. (Microfilm no.: NL7435). ↩

-

Marryat, F.S. (1848). Borneo and the Indian Archipelago: With drawings of costume and scenery. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Raffles, S.T. (1817; reprint 1830). The history of Java (vol. I and vol. II; 2nd ed.). London: J. Murray. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Low, H. (1848; reprint 1990). Sarawak: Its inhabitants and productions. Petaling Jaya: Delta. (Call no.: RSEA 915.954043 LOW-[TRA]). ↩

-

Spencer, B.S.J. (1862). Life in the forests of the Far East. London: Smith, Elder. (Microfilm no.: NL3636) ↩

-

Carey, P.B.R. (Ed.). (1992). The British in Java, 1811–1816: A Javanese account. London: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 325.341095982 PAN). ↩

-

Hannigan, T. (2012). Raffles and the British invasion of Java. Singapore: Monsoon Books. (Call no.: RSEA 959.82 HAN). ↩

-

Knapman, G. (2017). Race and British colonialism in Southeast Asia, 1770–1870: John Crawfurd and the politics of equality (pp. 158–160, 161). London: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 325.01 KNA). Knapman notes that Brooke had demanded payment from Rajah Muda in the form of a transaction of antimony. Upon his return to Sarawak, Rajah Muda was unable or unwilling to abide by their deal, and that was used as the justification for Brooke’s attack on the Raja Muda’s compound and his threat to begin an uprising. ↩

-

Swettenham, F.A. (1907). British Malaya: An account of the origin and progress of British influence in Malaya. London; New York: John Lane. (Microfilm no.: NL19101). ↩