From the Archives: The Work of Photographer KF Wong

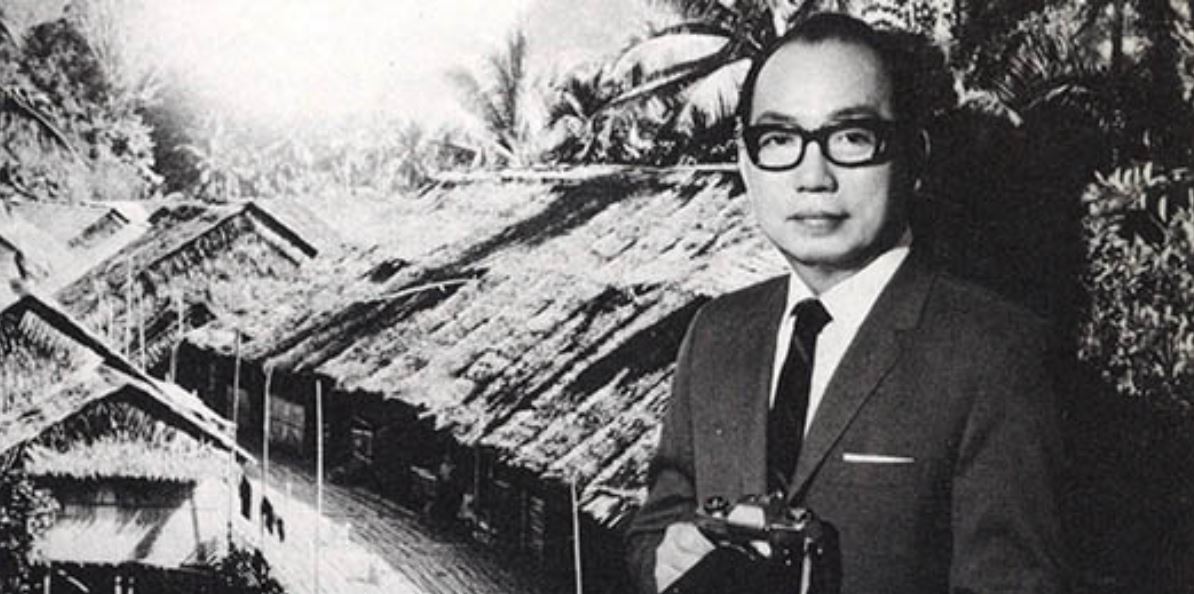

K.F. Wong shot to international fame with his images of Borneo, though not without controversy. Zhuang Wubin examines Wong’s work and sees beyond their historical value.

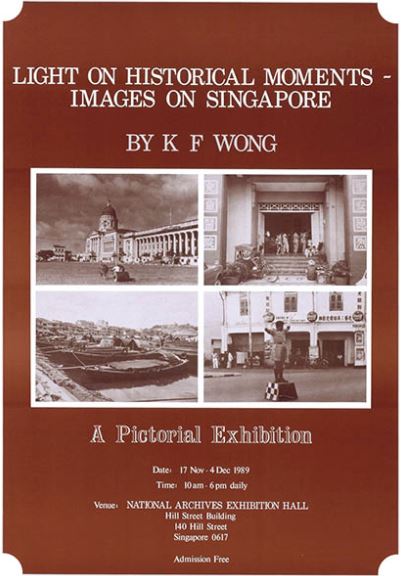

In 1989, exactly 30 years ago, the late Minister S. Rajaratnam officiated the opening of a solo exhibition by photographer Wong Ken Foo, more popularly known as K.F. Wong (1916–98). Organised by the National Archives of Singapore, “Light on Historical Moments – Images on Singapore” featured 159 photographs that Wong had taken from the mid-1940s to the 1960s.

This was a tumultuous period in Singaporean history: the British had returned after the end of the Japanese Occupation in 1945, and instead of being welcomed with open arms, they found a population resentful of their colonial masters. The political awakening among the people sparked a series of events that would eventually lead to self-government, and then full independence in 1965.

In his speech, Rajaratnam pointed out that an understanding of the “history of the private, everyday lives of Singaporeans”, however humdrum their daily routines might be, would be crucial in “moulding a Singaporean consciousness”.1 It is interesting that Wong, who was born in Sarawak, would be selected for this nation-building endeavour, even though he was by no means unfamiliar with Singapore.

In 1947, Wong and his friends opened Straits Photographers, a photo studio at Amber Mansions on Orchard Road. An advertisement in The Straits Times on 10 June 1948 highlighted his “artistic portraits and transparent oil painting[s]”.2 Wong ran the business as the studio manager until 1956, when he decided to return to his photography business in Sarawak.

Before opening Straits Photographers, Wong and his partners had already established the well-known Anna Studio in Kuching in 1938, followed by a branch bearing the same name in Sibu in 1941. Shuttling between the three studios kept Wong busy, but whenever he was in Singapore, he would head out before dawn to photograph street scenes, festivals and markets in the early morning light.3

In 1946, during a visit to Singapore, Wong photographed two bulls pulling a turf roller at the Padang. That photograph was a winner, clinching the top prize in the 1987 Historical Photographs Competition organised by the National Archives.4 Wong’s participation in the competition led to his aforementioned solo exhibition in 1989.

Earlier in June 1988, the National Archives had purchased over 2,000 photographs, mostly of Singapore, from Wong. Leading up to the exhibition, between 1988 and 1989, the Chinese daily Lianhe Zaobao published many of his old photographs of Singapore. Showcasing Wong’s old photographs was timely as the images bore testament to the country’s rapid growth and development since independence in 1965, and provided an important visual narrative of the young nation.5

A Self-made Photographer

K.F. Wong was born in the Henghua agricultural settlement of Sungai Merah in Sibu, Sarawak, in 1916. His parents were among the first group of Henghua migrants who had arrived from Fujian province in China and settled in Sibu in 1912. Most of them were poor Christian farmers who were recruited by missionaries through the regional Methodist network, spanning Xianyou county in the Putian region of eastern Fujian province to Sarawak in Borneo. In Sarawak, these farmers were employed by Charles Brooke, the “White Raja” of Sarawak6, to clear forested areas for agriculture.

Life was extremely tough in this part of Borneo, with tropical diseases and headhunters threatening the survival of the new immigrants. So many lives were lost at the time that there arose a popular Chinese saying in the community: “今日去埋人,明日被人埋” [“Today you help to bury someone, tomorrow you would be buried by others”]. Nevertheless, the migrants persevered, opening up more farming areas along the banks of Igan River in 1928 and Sungai Poi in 1929.7

Twice, Wong’s father moved the family back to China in the hope that his children would receive a better education. However, widespread banditry at his home village in Xianyou finally convinced him to bring his two boys back to Sarawak in 1932. While completing his lower secondary studies at the Chung Hua School in Sibu, Wong would spend his vacation time in his father’s plantation, where he befriended indigenous Iban8 workers and became enchanted by their stories and way of life.

Wong’s artistic talent was already apparent in school. Both his teacher and father wanted him to study at the Art Academy of Shanghai but he had already fallen in love with photography. Wong’s first encounter with the camera occurred when the school hired a studio photographer to take some pictures. Wong’s interest in photography was immediately piqued and he bought a Kodak box camera to dabble with. Winning the first prize of a school photography contest boosted his confidence. Unfortunately, his father disapproved of photography as a profession, dismissing it as an idle pastime for those who were not interested in proper work.9

In 1935, Wong left Sarawak to further his studies and hone his photography skills. His initial plan was to find a photo studio in Singapore where he could learn from a master photographer. He had set his eyes on Brilliant Studio (巴黎照相商店) on South Bridge Road, but was rejected even though he offered to work without salary for three years. The Cantonese, who dominated the photo studio business at the time, were unwilling to accept an apprentice from a different dialect group.10

Towards the end of 1935, Wong ended up in Quanzhou, China, and started apprenticing at Xia Guang Studio (夏光照相馆). To appease his father, Wong also studied art in a private art school, majoring in charcoal drawing. In 1937, he found work at the popular Anna Studio in Xiamen (the experience made such an impact that he named the photography business he would later open in Sarawak as Anna Studio).

Not long after, the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45) broke out, forcing Wong to flee Xiamen, bringing his wife and one-year-old daughter back to the countryside of Xianyou county before returning alone to Sarawak. He would be reunited with them only in 1975, almost 40 years later.

The Anna Studio in Kuching, which Wong opened in 1938, was originally located across the post office on Rock Road (on the stretch that has since been renamed Jalan Tun Abang Haji Openg). As his business grew, Wong became friends with people of all political persuasions and social class. The fame of Kuching’s Anna Studio spread far and wide, even reaching the ears of Japanese soldiers when Malaya and subsequently British Borneo fell to the Japanese Imperial Army in December 1941.

During the dark years of the Japanese Occupation, Wong was forced to keep Anna Studio open. Business remained brisk in Kuching as the Japanese soldiers enjoyed having their portraits taken. They would frequent his studio, often accompanied by “comfort women” – girls and women who were forced to provide sexual services to Japanese soldiers in occupied territories – some of whom were abducted from as far away as Bandung in West Java.11 It was during the Japanese Occupation when the studio moved to 16 Carpenter Street, the address that would witness the glory years of Kuching’s Anna Studio until its relocation in 1986 to Rubber Road.

Wong’s cordial relationship with his customers held him in good stead during the war years: towards the end of the Occupation, some of the younger Japanese officers who frequented Wong’s studio warned him to escape after learning that he would be arrested.12

Making His Mark

After the war, Wong’s reputation as a photographer grew. From around 1947 to the 1980s, his photographs were published in The Straits Times and the popular Straits Times Annual.13 Many of his single images featured political events, landscape views and portraits of important personalities in Sarawak and Brunei. He also published several photo essays detailing, for instance, a Malay wedding and the historical landmarks of Penang.

Wong continued to receive commissioned jobs through his studios in Singapore and Sarawak to take portraits of colonial officers, and photograph state functions, archaeological expeditions, movie stars and army servicemen. Some of these images appeared in The Straits Times as well as other publications outside of Singapore, taking on a journalistic slant. His photographs of Sarawak and, to a lesser extent, Brunei, helped to bring these territories closer to readers of The Straits Times in Malaya and Singapore.

Like most postwar practitioners of art photography, Wong was closely involved in the Pictorialism movement or, more colloquially, salon photography. In Southeast Asia, salon photography became increasingly popular with the rise of amateur photo clubs and competitions, which led to numerous exhibition opportunities. In 1950, Wong established his name in the First Open Photographic Exhibition hosted by the British-backed Singapore Art Society, clinching the silver medal for his work “Beauty’s Secret” – a still-life study of a vase of flowers – in the Pictorials section.

It was at the First Open Photographic Exhibition when Wong became acquainted with Malcolm MacDonald, Commissioner-General for Southeast Asia and a well-known art patron. MacDonald, who graced the exhibition opening, would became a firm supporter of Wong’s works, helping to entrench the latter’s name in the world of photography. MacDonald also wrote the introductory chapters to the two photobooks that Wong would later publish.

In the Second Open Photographic Exhibition in 1951, Wong bagged the silver medal again, this time in the Landscapes section for his work titled “A Symbol of Peace”, depicting a farmer tending to his field in Bali. It was the highest award given out for that year’s event, as there was no gold medal winner.

In 1955, Wong was made an Associate of The Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain (RPS) – one of the most prized accolades in salon photography. The following year, together with a few other amateur photographers, Wong helped to establish the Sarawak Photographic Society. In 1958, the society organised the first British Borneo Territories Photographic Exhibition in Kuching, with Wong as one of the jury members. Further recognition came in 1959 when he was elected a Fellow of RPS, having received full marks for each of his 12 entries that he had submitted in his bid for accreditation. At the time, Wong was only the second Chinese in Southeast Asia to have been awarded the fellowship.14

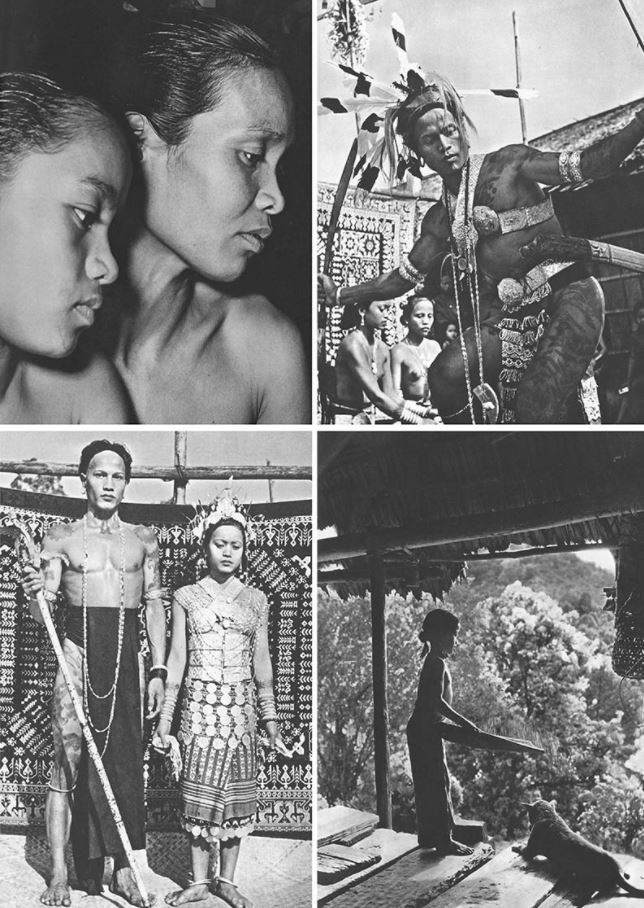

Photographing the Indigenous Peoples

By 1960, Wong had become one of the most decorated photographers in Asia. Although his winning submissions to salon contests included still-life studies and landscape photography, Wong truly distinguished himself from other competitors with his striking photographs of the indigenous Dayak peoples of Sarawak and, to a lesser extent, Sabah.15

Wong first began taking pictures of the Dayaks during the Japanese Occupation, and continued to visit the different communities, probably until the 1970s. Describing them as leading a “near-primitive life”, Wong wrote in 1960: “To feel satisfied with life, they need only food to feed themselves, the bare minimum in terms of clothing, and shelter from the sun. Without the material desire of the civilised man, they are the happiest people in the world.”16

While Wong’s photographs of the indigenous communities have important evidential value, his work is often clouded by his attempts to celebrate their primitive ways. Sunny Giam, a fellow salon photographer and frequent writer of photography for newspapers in Singapore in the 1950s and ’60s, wrote: “This genuine love for the natives, his desire to see the truth with his eyes, his rejection of all that is tragic in life and his exaltation of the happiness of the pagans, have enabled him to produce excellent photographs of them.”17

Visual sociologist Christine Horn, however, was more critical, taking Wong to task for romanticising the “traditional Indigenous lifestyle while suggesting that its extinction through the influence of development and modernisation was both unavoidable and desirable”. Horn also notes that Wong’s photographs were “created for the commercial market, and provided picturesque compositions of good-looking people in serene surroundings”.18

Indeed, many of Wong’s photographs were sold as souvenirs in his photo studios. Some of them were also submitted for salon competitions, which placed a premium on aesthetics and technical competency. In this sense, it is perhaps not surprising to learn that one of his iconic portraits of a Dayak girl was in fact created through darkroom manipulation, the analogue precursor to the cut-and-paste of modern-day Photoshop. The girl was photographed in Kapit in Sarawak, while the sakura tree in the same image had been shot in Kyoto, Japan.19

Nevertheless, Wong’s photographs attained an ethnographic dimension when they were published in newspapers, accompanied at times by “expert” accounts of the Sarawak indigenous peoples written by Christian priests and colonial officials.20 As Wong’s photographs circulated through newspapers and periodicals, his authority as the pre-eminent ethnographer of indigenous communities was further cemented. To this end, The Straits Times Annual played a crucial role.

In 1957, Vernon Bartlett, a former Member of Parliament in England and a journalist with The Straits Times in the 1950s, reviewed the 1957 edition of The Straits Times Annual. He praised it as a must-have Christmas gift for readers living in the West, who knew “Malaya only by proxy, through the letters of relatives and friends”. In the same review, Bartlett also expressed concern over Wong’s pictures of winsome Iban girls, which were so lovely that he rued the day when Sarawak might be “invaded by the kind of leering tourists” who had “done so much to destroy the unselfconscious beauty of Bali”.21 Through their circulation in the print media, Wong’s photographs of indigenous peoples helped put Sarawak on the global tourism map.

In 1953, on the occasion of Malcolm MacDonald’s visit to Kapit, the Sarawak colonial government appointed Wong as the official photographer. In one particular photograph, Wong captured MacDonald walking hand in hand with two bare-breasted Iban girls as they welcomed him to their longhouse. The conservative papers in Britain seized upon this image, insinuating that MacDonald had enjoyed a far-from-innocent relationship with the girls.22 Ironically, because of the controversy, Wong received even more requests from media agencies around the world to purchase the image, further enhancing his reputation.

Two Landmark Photobooks

Wong produced two acclaimed photobooks from his collection of photographs of indigenous peoples, which have since become collectors’ items. Pagan Innocence was published in London in 1960,23 possibly the first photobook on the Dayaks.24 In his introduction to the publication, Malcolm MacDonald proclaimed emphatically: “Mr K.F. Wong is a magician with his camera. Every photograph that he takes is a work of art.”25

Pagan Innocence is indeed an impressive photobook. Wong’s photographs are beautifully reproduced on the right-hand side of each spread, with the left page unadorned except for a single line of caption. The nudity depicted in Pagan Innocence made the book all the more infamous. Partly in anticipation of a backlash, a reviewer of the photobook took aim at those “fuddyduddies” who considered the female bosom as something shameful.26 The photobook became so popular that French and Swiss editions were later published.

Wong’s studio in Kuching was credited as the publisher of his second photobook, titled Borneo Scene (1979), with the printing undertaken by Chung Hwa Book Company in Hong Kong.27 Mak Fung, a veteran Hong Kong publisher and esteemed salon photographer, was the editor. Borneo Scene served a dual purpose: it not only showcased some of Wong’s greatest works, but was also pitched as a travel guide for potential visitors to Borneo, especially photographers.

The text makes clear the relationship between tourism and photography, pointing out the picturesque sights in different parts of Borneo for readers to visit and photograph. Given Wong’s life-long interest in indigenous peoples, there is also an ethnographic slant to the photobook. A closer look at the photographs reveal, for instance, the gradual covering up of exposed bosoms by the native women, a legacy of the impact of the “outside” world. Wong focused mainly on portraiture and festivities in the book, avoiding scenes showing the daily routine and hardships of the indigenous communities, except on rare occasions such as when he chanced upon a Penan tribe of nomadic hunter-gatherers preparing for the birth of a newborn in the forest.28

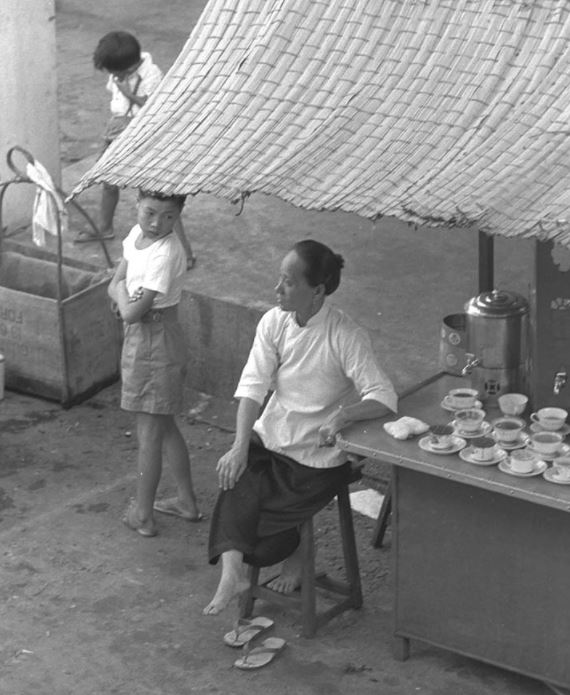

Scenes of Singapore

Most of the images credited to K.F. Wong found in the National Archives feature Singapore’s street scenes taken between 1945 and 1966. Apparently, by the late 1980s, Wong had given up staging his shots, a widespread practice in salon photography even today. Instead, he shifted his focus to the capture of fleeting moments and the myriad expressions of human life taking place on the streets.29

Nevertheless, Wong’s earlier photographs of Singapore prior to this change in direction still appear candid and natural. This is because Wong photographed situations and events where his presence would not be an issue – on busy temple days in Chinatown, during the frenetic Thaipusam procession, or when storytellers spun their magic on their earnest audiences by the Singapore River.

Wong’s oeuvre was broad; he also photographed labourers working in a pepper factory and documented the grittier side of life, such as the infamous Chinese death houses30 along Sago Lane in Chinatown. Esteemed local photographer Kouo Shang-Wei (1924–88), who shared a similar beginning in salon photography, held a much different view, chastising those who brought foreigners to places like Sago Lane.31

These days, Wong’s photographs in the National Archives tend to be featured in exhibitions and publications that illustrate the progress Singapore has made over the decades. Although Wong was the most titled salon photographer of his generation, and his photographs of indigenous peoples are still highly sought after by collectors today, his works are rarely shown at the National Gallery Singapore (NGS). This is surprising given NGS’ focus on the modern art of Southeast Asia.

The fact that Wong’s images are held in the National Archives conditions how we think about his work today – as archival and evidential in content. Perhaps it is time to reassess Wong’s work vis-à-vis his photographic contemporaries collected by the NGS to examine how photography is perceived by the arts community as well as the wider public in Singapore.

1948: “Annual Regatta Photographic Exhibition” (with Hedda Morrison), Chung Hua School, Sibu, Sarawak.

1958: “My Friends, The Dyaks”, Raffles Museum, Singapore.

1959: “K.F. Wong Solo Exhibition”, Chinese Photographic Association of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

1983: “黄杰夫作品展览” [“K. F. Wong Exhibition”], National Art Museum of China, Beijing, China.

1989: “Light on Historical Moments – Images on Singapore”, National Archives Exhibition Hall, Singapore.

2017: “Indigenous Grace”, Old Court House, Rainforest Fringe Festival, Sarawak.

Zhuang Wubin is a writer focusing on the photographic practices of Southeast Asia. He is a former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow at the National Library of Singapore, and a recipient of the Robert H.N. Ho Family Foundation Greater China Research Grant 2018.

Zhuang Wubin is a writer focusing on the photographic practices of Southeast Asia. He is a former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow at the National Library of Singapore, and a recipient of the Robert H.N. Ho Family Foundation Greater China Research Grant 2018.

NOTES

-

Knowledge of past important in shaping consciousness, says Raja. (1989, November 17). The Straits Times, p. 30. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 12 advertisements column 1. (1948, June 10). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

莫美颜 [Mo, M.Y.]. (1989, November 12). 快门霎那捕捉永恒 [Shutter in a split-second captured eternity]. 联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], p. 6; 李永乐 [Li, Y.L.]. (1989, November 12). 拥抱往事 [Embrace the past]. 联合晚报 [Lianhe Wanbao], p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hoe, I. (1987, March 6). 41-year wait for the big winner. The Straits Times, Home, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

王玉云 [Wang, Y.Y.]. (1988, November 20). 黄杰夫辗过历史 [K.F. Wong traverses history]. 联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The White Rajahs were a dynastic monarchy of the British Brooke family, who ruled Sarawak from 1841 to 1946. The first White Rajah was James Brooke, who ruled until his death in 1868. As a reward for helping the Sultan of Brunei suppress “insurgency” among the indigenous peoples, Brooke was made the Rajah of Sarawak. ↩

-

房汉佳 & 林韶华 [Fong, H.K., & Lim, S.H.]. (1995). 《世界著名摄影师黄杰夫》 [World famous photographer K.F. Wong] (pp. 9–10). 福州: 海潮摄影艺术出版社. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

The Ibans or Sea Dayaks are a subgroup of the Dayak, the indigenous peoples of Borneo. Most Ibans are located in Sarawak. ↩

-

Fong & Lim, 1995, p. 24. ↩

-

Fong & Lim, 1995, p. 25. ↩

-

Fong & Lim, 1995, p. 39. ↩

-

K F Wong’s reflection of life. (1998, October 18). Sarawak Tribune, Panorama. (Not available in NLB holdings). ↩

-

K.F. Wong’s photographs also appeared in Straits Times Pictures 1948 and Straits Times Pictures 1949. Published by The Straits Times, these are annual compilations of photographs taken by staff photographers and other prominent practitioners from Malaya and British Borneo. ↩

-

Sarawak Tribune, 1998. ↩

-

Giam, S. (1960, August 4). Genuine love for the Dyaks made him outstanding photographer. The Singapore Free Press, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wong, K.F. (1960, September). 风土摄影十五年 [Fifteen years of photography in Borneo]. Photoart, 12. (Not available in NLB holdings). ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 4 Aug 1960, p. 8. ↩

-

Horn, C. (2015). The Orang Ulu and the museum: Investigating traces of collaboration and agency in ethnographic photographs from the Sarawak Museum in Malaysia (p. 139) [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Melbourne, Australia: Swinburne University of Technology. (Not available in NLB holdings). ↩

-

Fong & Lim, 1995, p. 106. ↩

-

Howell, W. (1948, June 21). The Sea Dyaks of Borneo. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Bartlett, V. (1957, October 27). It is really a winner. The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sanger, C. (1995). Malcolm MacDonald: Bringing an end to empire (p. 329). Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press. (Call no.: RSING 941.082092 SAN) [Note: I would like to thank Alexander Shaw for pointing out this reference.] ↩

-

Wong, K.F. (1960). Pagan innocence. London: Jonathan Cape. (Call no.: RCLOS 991.12 WON-[GBH]). ↩

-

Sarawak Tribune, 1998. ↩

-

MacDonald, M. (1960). Introduction. In Pagan innocence (p. 7). London: Jonathan Cape. (Call no.: RCLOS 991.12 WON-[GBH]). ↩

-

Romney, H. (1960, October 24). Caught with the camera: The Dyaks in a passing moment. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wong, K. F. (1979). Borneo scene. Kuching: Anna Photo Company. (Call no.: RSEA q959.52 WON). ↩

-

Loh, T.L. (1989, November 16). Life seen through a Leica. The New Paper, p. 11; 莫洁莹 [Mo, J. Y.]. (1987, September 22). 摄影家黄杰夫的新路向:反映人生百态 贵在追求自然 [The new direction of master photographer K.F. Wong: Reflect the different dimensions of human life, with an emphasis on the pursuit of candid moments]. 联合晚报 [Lianhe Wanbao], Domestic News, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

These were funeral houses where people without kin would live and wait out their last days. In the late 19th century, death houses began sprouting in Sago Lane. Many shops selling funeral items also opened along the street. Death houses were banned in 1961. ↩

-

郭尚慰 [Kouo, S.W.]. (1981, July 3). 我为全斗焕总统访新铺路 [I paved the way for President Chun Doo-hwan’s visit to Singapore]. 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. See Zhuang, W. (2018). Kouo Shang-Wei: An introduction. In Shifting currents: Glimpses of a changing nation. Singapore: National Library Board, p. 21. (Call no.: RSING 915.957 KOU-[TRA]). ↩