On Writers and Their Manuscripts

No great work of literature is completed in just one draft. In an age where writers have gone paperless, novelist Meira Chand ponders over the value of manuscripts, and what they might reveal about a writer’s thought process.

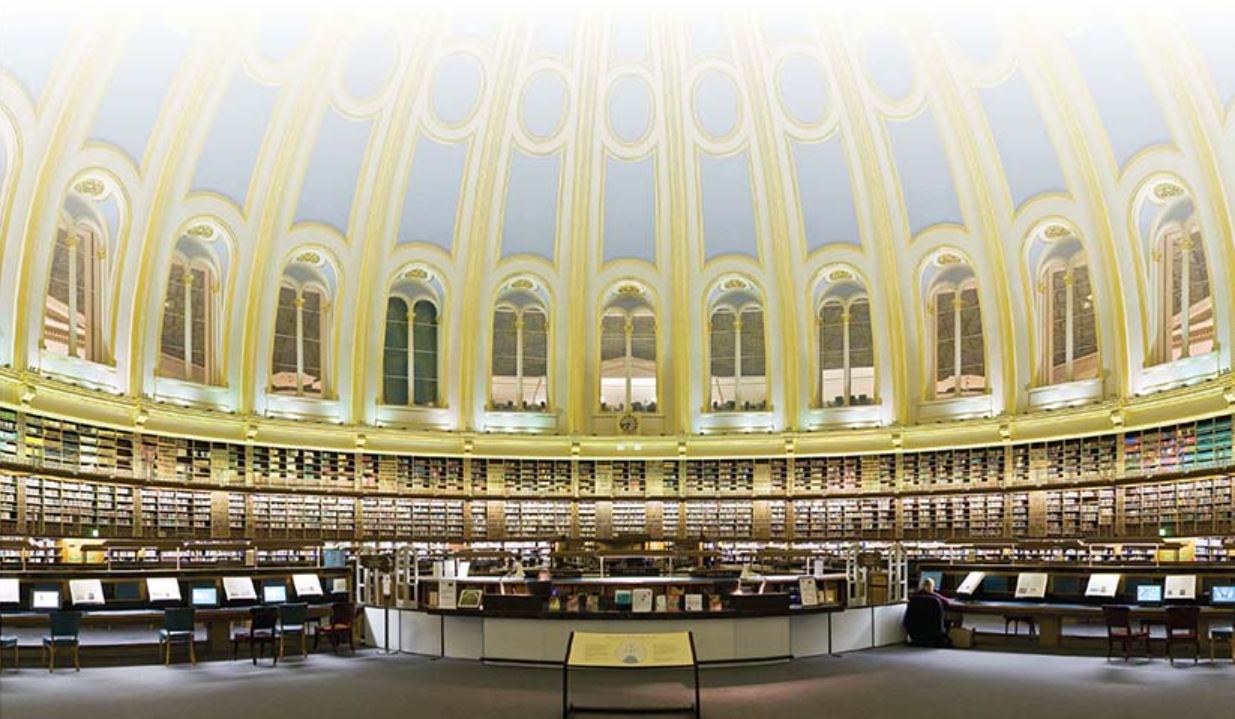

As a young writer many years ago, it thrilled me to go to the Reading Room of the British Museum in London. This massive circular room with a soaring glass-domed ceiling opened in 1857, and it quickly became a mecca for writers from all over the world, who came here to research and write, and breathe in its rarefied literary atmosphere.

Until its closure in 1997 and its transformation into an exhibition space in the British Museum, many famous writers and luminaries used the Reading Room, including the likes of Oscar Wilde, Karl Marx, Sun Yat Sen, George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells, Virginia Woolf and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, to name but a few.

There were glass cases in the Reading Room, in which were displayed the handwritten manuscripts of famous authors: Charles Dickens, Jane Austen and many more. I used to stare at these sheets of paper in awe. Thin and yellowed with age, they were crammed with inky words that, in a long ago moment, had fallen fresh from the minds of these great writers.

A flow and urgency were apparent in the writing, the dark hatching of corrections thick upon the pages, as were the occasional ink blobs, smears and fingerprints. So much of the writer’s emotion seemed evident in the handwriting, in the choice of paper, and even the strength of the pen marks. It was humbling to realise that before me was the rawness of the creative process in the seminal moments of a classic work.

This moment is beautifully described by Agatha Christie:

“You start into it, inflamed by an idea, full of hope, full indeed of confidence… know just how you are going to write it, rush for a pencil, and start in an exercise book buoyed up with exaltation. You then get into difficulties, don’t see your way out, and finally manage to accomplish more or less what you first meant to accomplish, though losing confidence all the time. Having finished it, you know it is absolutely rotten. A couple of months later you wonder if it may not be all right after all.”

Whenever I pick up, in a library or bookshop, the published volumes of those very manuscripts I had gazed at in awe in the British Museum – still being printed and read by modern readers – I can only marvel at the unchanging quality of the writer’s imagination through time. These memories came back to me recently in Singapore when I donated my own manuscripts and associated research materials to the National Library.

In the digital age, most, if not all, work is produced on a computer, the document saved to a file in the hard drive and finally emailed to a publisher, who will likely read it on a computer screen. Increasingly, writers accumulate paperless manuscripts and, because of this, original handwritten manuscripts, such as those of the classics I saw in the British Museum, hold ever more fascination for us.

Old habits die hard, and although I now work in a largely paperless way, I still like to correct and edit on a printed hard copy. When I began my career as a young writer in the days before computers, manuscripts were bulky things comprising many physical drafts. As a result, the writer invariably ended up with stacks of paper, boxed or bound with string, all heavily worked with corrections and edits.

Not yet published and unsure of my own worth as a writer in those early days, it was easy to question the value of storing so much paper and, in exasperation, sometimes even throwing it all away. Indeed, I did dispose of early typed drafts of my first novel, thinking them to be of no consequence until my first publisher in London alerted me to the fact that I might regret such impulsive action at a future stage in my writing career. I understood this sentiment when I made my donation to the National Library.

I have written nine novels over several decades, but have lived an itinerant life for the most part, residing for long periods of time in different parts of the world. After several decades of living in Japan I finally made my way to Singapore in 1997; among the things I brought with me were drafts of some of my novels. As a professional novelist, I have continued to write through my long residence in Singapore. As the number of my published books accumulated, so have the paper drafts of those works that I still need to work on. Over the years, the boxes of stored manuscripts have taken over my study, stacked shoulder high, the span of my writing life grown up like a forest around me.

When the librarians from the National Library came to view the materials, it amused me to see how delighted they were at the emergence of the most heavily worked manuscripts. Not only were these manuscripts thickly pencilled upon with corrections, but many pages were, quite literally, cut and pasted together. In the days before computers, this is what all writers did – a pair of scissors and a tube of glue were part of any writer’s kit. When I now click the “cut” button on my Mac, and then slide the cursor down and select “paste”, I never fail to draw a breath of deep gratitude for the wonders of modern technology.

While assessing and sorting through the many boxes in my study, the National Library people noticed that most of the manuscripts were of my later books. “Where are your earliest handwritten manuscripts?” they asked me. Although I had indeed handwritten my first four novels, and laboriously typed them up on an old typewriter, in the intervening years of relocating from one place to another, I had forgotten where I had stored them. But I was certain they were not lost.

Manuscripts do get lost for many different reasons, and there have been some famous losses in history. In 1597, the playwright Ben Johnson, a contemporary of William Shakespeare, wrote a play, The Isle of Dogs. The subject matter so offended the government that Johnson was arrested and orders given to burn his script. Unfortunately, there is no record of the contents of the play; we only know that it was written by Johnson and subsequently fell victim to the censorship of the day.

In more modern times, the Polish Jewish writer Bruno Schultz, aware of the threat to his life (he was murdered by the Nazis in 1942), entrusted the manuscript of his last novel, The Messiah, to the care of friends. After his death, his biographer searched in vain among his friends for this missing work. The manuscript has never been found.

Following her suicide in 1963, Sylvia Plath’s estranged husband, Ted Hughes, destroyed her last writings because he did not wish their children to read the contents. Similarly, William Blake’s literary executor deliberately destroyed some of his works, believing that they were inspired by the Devil no less.

Many writers, such as James Joyce, destroy their own work for reasons known only to them. Joyce destroyed an early play, A Brilliant Career, leaving just the title page with the words “To my own soul I dedicate the first true work of my life”. The poet Philip Larkin kept very personal diaries throughout his life, but wished them destroyed upon his death as he did not want controversial elements of his life to be revealed. His request was honoured by his long-time secretary, who burned the lot.

My own early manuscripts were not lost for any such dramatic reason; I had just forgotten where I had stored them.

Last summer, with my family, I visited a home I still own in the mountains of Nagano, northwest of Tokyo, the residue of my many years in Japan. The house has a dusty attic that, to my grandchildren, was magically intriguing. Exploring the attic in excitement, they found, under a pile of old carpets, a leather suitcase and four large boxes of manuscripts. I had forgotten I had stored them there when relocating to Singapore, and hadn’t noticed them beneath the carpets while previously cleaning out the attic. I was filled with enormous relief and emotion at the sight of all this yellowing paper, as if a lost child had been returned to me.

In the boxes and suitcase that I unpacked upon my return to Singapore, the many notebooks and binders in which I had handwritten my first four novels finally emerged. I also found the early typed drafts of these novels, all heavily cushioned by the literal cutting and pasting together of text that I did in those days.

It was a strange feeling to open up those old dog-eared exercise books, to look down at the flow of my own firm writing, and to see the pressure of emotion, the urgency to capture the torrent of thoughts, the cross-hatching of corrections, the smears and finger-marks, the stain of a coffee cup. And remembering how I had stood before the writings of Dickens and so many other literary immortals in the Reading Room of the British Museum so long ago, I felt humbled to have shared with every writer across time, in my own very small way, the miracle of our human imagination. Walt Whitman described it most evocatively:

“The secret of it all, is to write in the gush, the throb, the flood of the moment – to put things down without deliberation – without worrying about their style – without waiting for a fit time and place… By writing at the instant, the very heartbeat of life is caught.”

Philosophers have examined the miracle of the imagination across the ages, from Sophocles to Paracelsus to those of our modern times. Breaking with earlier ideas about the source of the imagination, the philosopher Immanuel Kant saw it as the hidden condition of all knowledge. He speaks of it as being transcendental, of grounding the objectivity of the object in the subjectivity of the subject. To Kant, the imagination preconditions our very experience of the world, rather than coming from a transcendent place beyond man, as some earlier philosophers suggested.

To the writer, however, when caught in the heat of inspiration, the seemingly unstoppable flow of words can come only from a Divine Mind. The poet William Wordsworth provides a wonderful metaphor for the way all writers feel when writing. He speaks of withdrawing from the world to the “watchtower” of his solitary spirit. Perhaps it is this heightened state of awareness and its connection to our common humanity that the writer seems able to command that imbues literary manuscripts with such romantic power for the public.

In our modern world, the interest in literary manuscripts has grown enormously. Many institutions, particularly in the United States and the United Kingdom, spend large sums of money to acquire the manuscripts of famous writers. Two hundred years ago, nobody would have bothered to archive contemporary literary work. Today, in the digital age, manuscripts have acquired both a meaningful and a magical value.

For the student of literature, the meaningful is found in what a writer has cut out or changed in the manuscript, the variations of each draft presenting a mental map of the writer’s intention, struggle and literary journey. The magic, however, is found in the mystery of artistic genius. While viewing a manuscript, we can, as it were, stand at the author’s side at the very moment their imagination is pushed beyond the boundaries of human ability.

Literature’s invaluable gift to society is found in the human sharing of spirit and experience. The reader enters the writer’s mind, and the writer enters the reader’s mind. Together, they journey through the imagination to unknown worlds and to those deepest parts within us. It is this wish to share in the direct experience of the writer that fuels the push within libraries and archival institutions around the world to build archives of primary materials.

This is why the librarians from the National Library welcomed my own humble, handwritten exercise books, the sheets of manuscript padded with pieces of cut and pasted text, and even an unrelated shopping list hastily scribbled into a margin. The extraordinary journey of literary creation holds us in awe as we view a manuscript. From the intimacy of the written page, the writer appears to reach out across time and space, linking us in direct and authentic experience to the work being produced.

THE MAGIC OF MANUSCRIPTS

By Michelle Heng, Literary Arts Librarian, National Library, Singapore.

Dr Meira Chand’s first donation to the National Library, Singapore, in 2014 included manuscripts, typescripts and research materials relating to drafts for A Different Sky (Random House: London, 2010), an Oprah Winfrey-recommended novel that follows the arc of modern Singapore history.

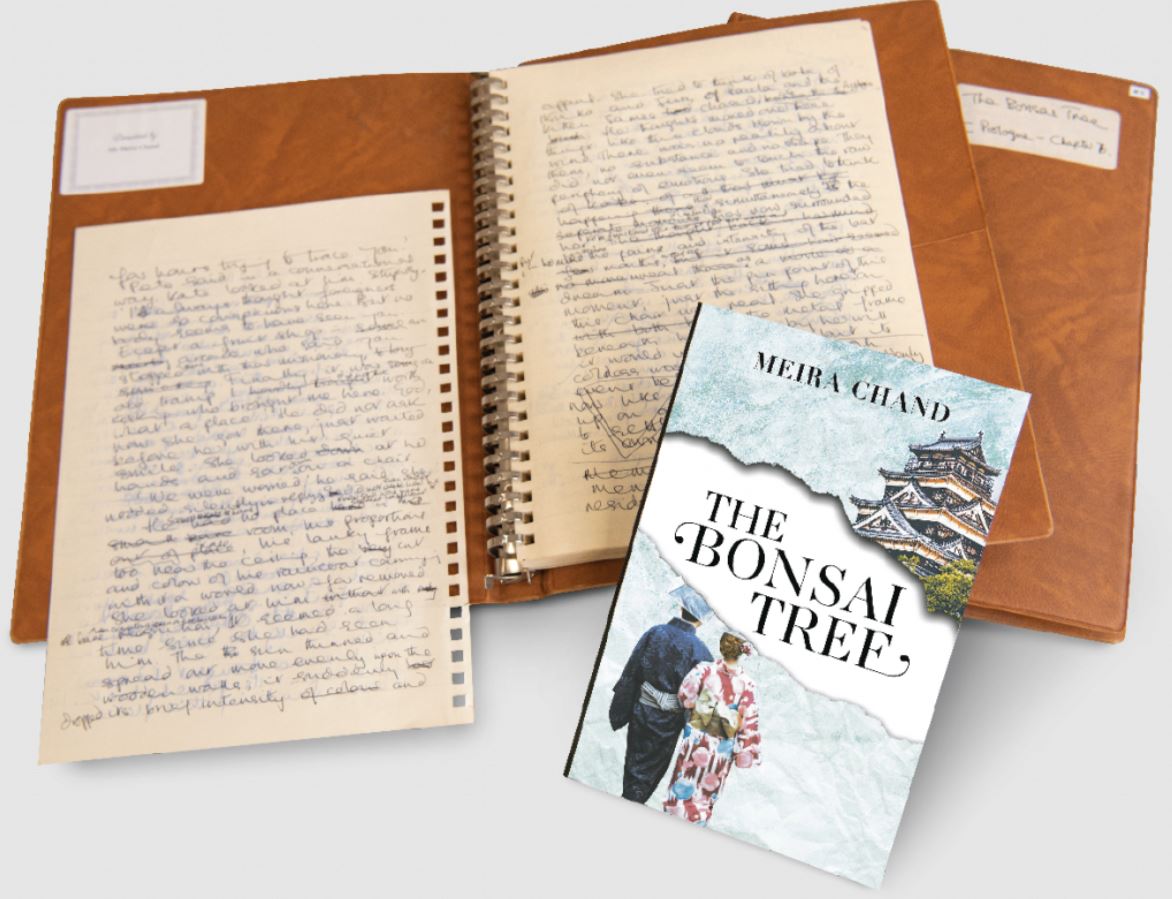

Her most recent donation in 2018 includes typescripts of The Bonsai Tree (John Murray: London, 1983), a novel about a young English woman who marries the Japanese heir to a textile empire and her many travails at a time when foreigners were reviled by conservative Japanese society. The author’s reworked editions and handwritten markings on these typescripts offer a glimpse into the painstaking process that goes into the birth of a literary work. The British Book News stated in October 1983 that, “The Bonsai Tree is a considerable achievement both as a novel and as a social document…”

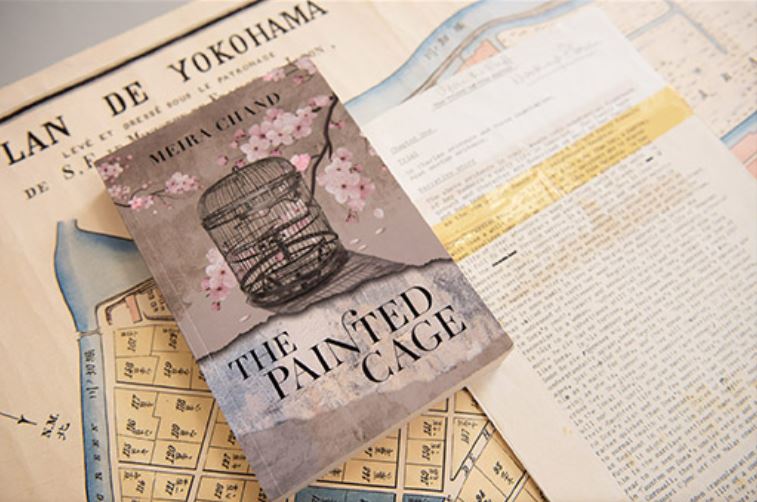

While living in Japan, the author visited various museums and heritage sites to gather information for her early novels. These Japanese- and English-language ephemera – including brochures and booklets – on old European-style mansions inhabited by expatriates in Japan from the mid-19th to early 20th-century were donated to the National Library, along with a reproduction of a 1865 plan of the Yokohama Foreign Settlement. The author used these materials as research for The Painted Cage (Century Hutchinson: London, 1986), a murder mystery set in 1890s Yokohama that was longlisted for the Booker Prize in 1986 and reissued by Marshall Cavendish (Singapore) in 2018.

Meira Chand’s authorial drafts and research materials capture the magic of a writer’s creative process and provide a fascinating behind-the-scenes peek into her works. One of the key functions of the National Library is the collection and preservation of documentary materials relating to Singapore’s history and heritage. Dr Chand’s donation to the library’s Donor Collection augments the growing collection of research materials gifted by authors associated with Singapore’s literary development.

Dr Meira Chand’s nine novels reflect her multicultural experiences, having lived in Japan and India before moving to Singapore in 1997. A National Library Distinguished Reader, she has a PhD in creative writing from the University of Western Australia and is actively engaged in nurturing young Singaporean writers.

Dr Meira Chand’s nine novels reflect her multicultural experiences, having lived in Japan and India before moving to Singapore in 1997. A National Library Distinguished Reader, she has a PhD in creative writing from the University of Western Australia and is actively engaged in nurturing young Singaporean writers.

REFERENCES

Brock, J.A. (2018, January 8). 100+ famous authors and their writing spaces. The Writing Cooperative. Retrieved 2019, April 29, from The Writing Cooperative website.

Gioia, D. (1996). The magical value of manuscripts. The Hudson Review. Retrieved 2019, April 29, from Dana Gioia website.