Fleeing to Uncertainty: My Father’s Story

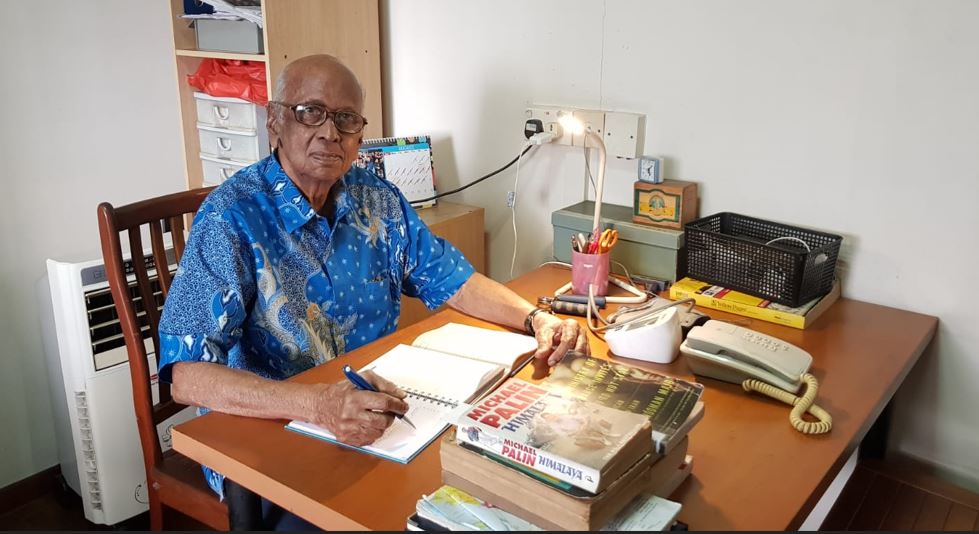

Barely 13 years old then, K. Ramakanthan and his family escaped with their lives from Perak to Johor during the Japanese Occupation. Aishwariyaa Ramakanthan recounts her father’s harrowing journey.

My father’s scramble to safety in the final days before the fall of Malaya to the Japanese in December 1941 is regular fodder for teatime conversation with my parents. I grew up listening to my father tell of his harrowing escape, but it is his ability to recount the journey in such fascinating detail that inspired me to write about it.

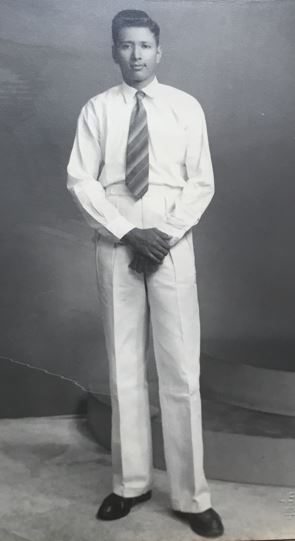

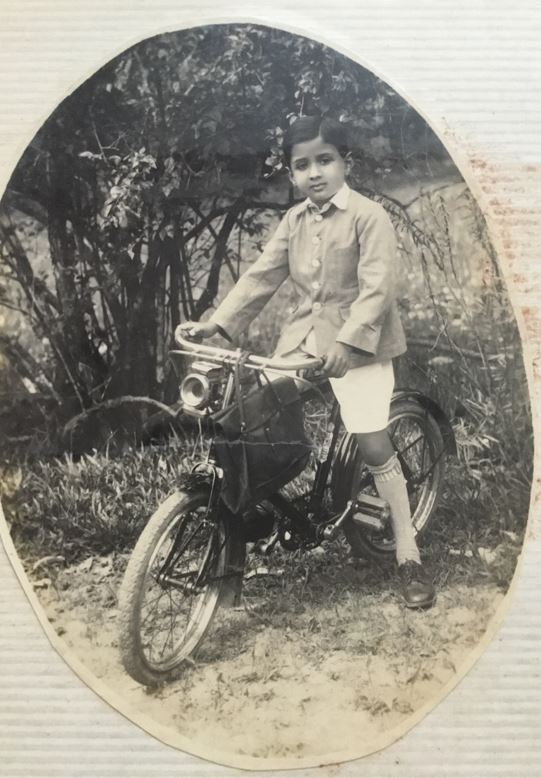

My father, K. Ramakanthan, was born in December 1929 in Bruas (Beruas), Pahang, and later moved to Perak with his family. His father’s beginnings were quite similar to those of early migrants from South India looking for a better life in Malaya.

My grandfather had arrived in Malaya on board the Rhona with his young wife, starry-eyed and full of hope, like many others on that ship. After early struggles to find employment, he secured a reasonably well-paying job at a rubber plantation in Perak. This enabled him to buy his family a few luxuries – like a treasured Austin 7 car for one.

Having settled down to life in Perak, my grandfather did not imagine even for a moment – like so many others who blindly believed in the invincibility of the British – that they would have to flee for their lives one day. When the Japanese invaded Malaya during World War II, my grandfather lost everything that he had worked so hard for.

This is my father’s story.

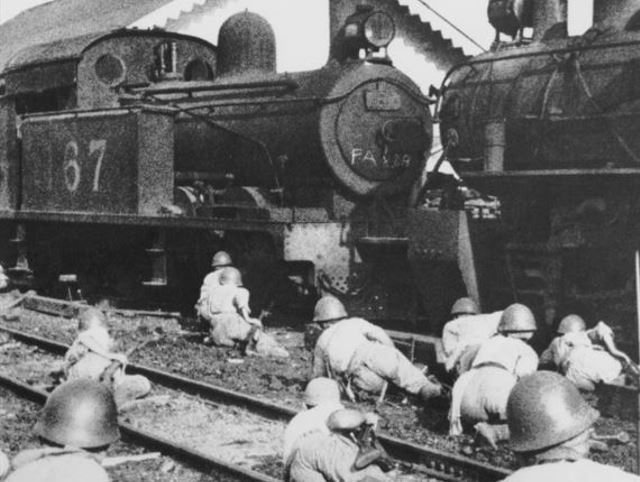

My first sense that the world I knew would collapse was when I was waiting to take the train back home from school one Friday afternoon in late 1941. People were moving hurriedly with packed bags, their faces etched with tension and worry. I was puzzled when a man walking past whispered in Malay: “Jepun datang. Lekas balik.” (“The Japanese are coming. Go home quickly”).

I hurried home only to discover that a large group of Indian soldiers from the British Army had assembled in the open space in front of our home. Why they were there we didn’t quite know, but my mother was clearly disturbed at this sight. My father, however, brushed her worries aside, convinced that the whispered rumours were untrue. Above anything else, he was certain that the might of the British Empire would prevail. So we went about our usual routine that Friday, unaware that our lives were about to change in ways we could never have imagined.

I remember spending the day reading my favourite Rainbow comics and playing with my two baby brothers. I knew of Benito Mussolini, the fascist prime minister of Italy, from a Beano comic strip that caricatured him as the ridiculously pompous Musso the Wop. Adolf Hitler of Germany had been similarly portrayed as a laughable character in Charlie Chaplin’s film, The Great Dictator. Perhaps these depictions of evil men who had been caricatured as idiotic and harmless had lulled me into a false sense of security.

Saturday dawned in a deathly silence. I peered out of my bedroom window but the soldiers in front of my house were no longer there. My father left for work as usual while my mother and I played with my brothers on the verandah. The peace was suddenly shattered by my father’s return in his Austin 7. We watched aghast, completely confused as he drove up like a madman, gesticulating wildly. The car screeched to a halt and he jumped out yelling, “Pack up! Pack up! They are here! They are here”! It didn’t strike us immediately that he was talking about the Japanese.

He rushed around frantically gathering what he could, telling us to do the same while trying to explain that the Japanese were gaining ground. In our shock, we grabbed whatever seemed most valuable and necessary at the time – money, jewellery and some clothes. Everything else was left behind, including a prized gramophone that had provided hours of entertainment and my Hornby clockwork train set, a gift from my uncle.

As father’s little Austin 7 could only accommodate my mother, my younger brothers, a female cousin who was living with us at the time, and our belongings, I was put in the care of a trusted family friend and his family to travel by train to Kuala Lumpur, about 200 miles from our home in Perak.

As I watched my parents drive away after dropping me off at the railway station, I felt a palpable sense of excitement at the thought of being plunged into an adventure of the sort I had only read about in books. But at the same time I was fearful that I would not see my family again. At the station, I saw people with bags, children, pets and chickens in tow rushing towards the waiting train – their ticket to safety. Men, women, children, the young and the old clambered over each other, fighting to get onto a train that was already bursting at its seams.

I fought off sleep as the overnight train chugged towards Kuala Lumpur, picking up more people along the way. The train pulled into Kuala Lumpur at about five the next morning. Staying together was a struggle as we made our way past the heaving mass of passengers. When we finally emerged from the cramped train, the fresh air that greeted us was a welcome respite, and we took deep gulps of it. For a minute, we forgot the gravity of our situation.

Acting on my father’s instructions, my guardian dropped me off at Lakshmi Vilas on Ampang Street, a popular Indian vegetarian restaurant in Kuala Lumpur in those days. Alone now, I anxiously scanned the crowd in the restaurant and the street outside, hoping for a glimpse of my family. Suddenly, a piercing “Wooo-oo-oo!” sound ripped through the air, rising to a crescendo. It was the air-raid siren. Pandemonium ensued, and people started shouting and screaming as they made a mad dash for the air-raid shelters.

Paralysed with fear, I stood rooted to the ground not knowing what to do. None of the war stories I read had prepared me for this.

Suddenly, I felt a heavy hand on my shoulder. It was the restaurant manager. He grabbed my arm and we ran into the shelter just as the first bombs hit. It was a full 10 to 15 minutes before the “all clear” signal sounded. People sighed with relief, thankful that they were still standing even as their legs trembled.

A grim sight met us as we emerged into the blinding sunlight. Many buildings had been badly damaged, and several dead bodies littered the streets. The restaurant, miraculously, was still intact. Among the casualties were the wife and two sons of the family friend who had accompanied me to Kuala Lumpur – although I wasn’t aware of this at the time. When my own family finally turned up at the restaurant, my relief and joy knew no bounds.

My father then drove to his office headquarters in Kuala Lumpur to inform them of his whereabouts. There, his British boss (or “Tuan” which means “master”, the Malay term of deference locals used to address their colonial superiors) pressed my father to let him borrow the Austin 7 to drive to Singapore, as he needed another car to accommodate his whole family. My father had no choice but to agree. His Tuan, like the rest of the British, believed that Singapore was a stronghold that would not fall to enemy attack – the British called the island the “Gibraltar of the East” in reference to its European bastion at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula.

We spent the night at the abandoned house of a family friend. The next morning, my father went to look for a taxi to take us to Muar, while the rest of us prepared to leave. Just as we finished lunch, the ominous sound of the siren tore through the air again. With pounding hearts, we took cover under a staircase, the only shelter available. This time it finally dawned on me that death was a real possibility. We covered our heads and clung tightly to each other as the ground under us shook. My mother urged us to be calm and brave, and to pray – which we did, fervently.

We didn’t realise how lucky we were to be alive until we emerged and saw shrapnel embedded in the walls outside the house, deep craters in the streets and buildings ablaze. The bombings, which lasted around 30 minutes, felt like an eternity. We were relieved only when father returned, safe and sound, in a taxi. Gathering our few belongings, we made our way to Muar, arriving at my uncle’s house just before nightfall. We were thankful to be with our relatives, but the respite was brief.

Tired of being cooped up all day, the following afternoon at around four, my father and I decided to take a walk. The cloudless blue sky was so beguilingly attractive that we soon let our guard down. Squinting at the sun, I spied in the distance some glinting silver objects falling from the sky. I tugged at my father and pointed upwards. He took one look at the sky before grabbing my arm and started to run. Just as we entered the house and shut the door, we heard the drone of low-flying planes.

All of us instinctively dived under a bench in the storeroom. Trembling, we could hear the bombs raining down on Muar town and the river. The assault sank a cargo vessel that had been travelling upstream with supplies for people living along the river banks. The 30-minute bombing blitz was meant as a warning to instill fear, for the Japanese could have obliterated the town if they had wanted to.

As soon as the air raids stopped, we and several other Indian families in the small town gathered for a quick meeting. We decided to leave Muar for Batu Pahat as a group – it somehow felt safer to move around in large numbers. We chose to travel inland, away from the main thoroughfares. But once again, despite the life-and-death predicament of his own family, duty called upon my father: he was instructed by his British boss to meet him in Singapore (we would lose all contact with my father for several weeks after this, but were later reunited). The rest of the family journeyed without my father to Batu Pahat as part of a convoy of cars heading south in the general direction of Johor and Singapore.

Overcome by tension and fear, the convoy soon separated. Some cars headed towards Yong Peng, while others towards Pagoh and Segamat; still others drove inland into remote villages. En route to Batu Pahat in my uncle’s car, we could heard the drone of airplanes. My uncle floored the accelerator and drove towards the town, to the house of someone he knew, who very kindly agreed to accommodate us. The most wonderful thing about those troubled times was that people were willing to open their homes to those in need.

Just as we arrived, the bombings began and sent us scurrying for safety in the house. When all was quiet once again, we gingerly peered out the window. A few bodies were strewn on the street, and there was a huge crater not 50 yards from the house. One of the bombs had just missed us by a whisker.

The next day, the friend suggested that we move to Sankokoshi Estate, a Japanese-owned oil palm plantation, which he thought would be safer. We were to occupy one of the abandoned houses there, a Japanese-style house with sliding doors and tatami mats on the floor. We shared this house with a few other families.

I spent the next few days exploring the grounds of the beautiful estate, oblivious to the worries of the adults or even to my mother’s fears about my father who still had not returned from Singapore. Fruit trees with low-hanging guavas and mangoes, a stream teeming with fish, and abandoned railway trolleys meant for transporting palm fruit were enough to keep me and the other children occupied. The women helped each other with the cooking, while the men fortified the place as best as they could. They gathered sticks, fashioned homemade spears and other weapons for protection, and cycled to nearby villages to buy supplies and groceries.

A few days later, a squadron of Japanese planes swooped low over the estate. We watched the planes as they headed south towards Singapore to celebrate Japan’s victory. The Gibraltar of the East had evidently fallen, signalling the start of the Japanese Occupation – and the beginning of three-and-a-half-years of untold suffering and atrocities.

Several uneventful weeks had passed. One particularly warm night, the men had just finished playing cards, the only entertainment available, while the women were chatting or looking after their children. Soon, the adults began turning in for the night. The women and children slept indoors, while the men slept outside on the verandah surrounding the house.

Sometime around midnight, the dog Somu, which belonged to a Dr Sharma, one of the men in the community, let out a long, rumbling growl that suddenly erupted into ferocious barking. We were jolted out of slumber. The household stirred and concerned voices called out in the dark. Before anyone could stagger to their feet to determine the cause of Somu’s barking, the clatter of heavy boots was heard, followed by harsh cursing in Japanese. We were instantly awake, attentive and frightened – very frightened.

“Kara kura!” snapped the man who seemed to be the sergeant. By now we knew enough Japanese to know that the phrase meant “Hurry up! Pay attention!” He was a short, squat fellow with an expression of ferocity that matched Somu’s bark. Somu was barking his head off by now, and Dr Sharma was desperately holding the wriggling dog and trying to calm him, but to no avail. In a split second, we saw a glint of steel and a sword pointing at the terrified doctor.

The rest of us were paralysed with fear and at a loss as how to help the doctor. Dr Sharma immediately fell at the feet of the sergeant begging for his life. And then, the most amazing thing happened. As if on cue, Somu stopped barking and began to whine and follow his master’s example. He, too, crawled up to the sergeant on his stomach, as if in total supplication, while the rest of us watched open-mouthed.

The scene was so surreally funny that even the Japanese sergeant chuckled. That was enough for the rest of us to start laughing, violent paroxysms that were induced by a combination of fear and relief, and the comic despair of it all. The pudgy soldier exclaimed, “Yoroshi!” (“Good!”) He appeared to have softened a little. He eyed us and then reached out and ruffled my hair, saying, “Kodomo tachi! Yoroshi!” (“Young fellow! Good!”). The tension evaporated and the mood lightened. But we relaxed a little too soon. It appeared that the sergeant was a little temperamental.

“We want borrow car! You give?” asked the sergeant in broken English. When Dr Sharma responded “Sorry, no petrol”, the sergeant flew into a rage. “No petrol, no petrol, all die! Boom!” he snapped, all the while gesticulating wildly. When two canisters of petrol were miraculously produced by someone in our group, he calmed down. “We borrow car and give receipt. We return car in Muar,” he promised. “Ok! Arigato gozaimasu!” (“Ok! Thank you”) he barked, and all his men piled into the car and drove off into the night.

In the weeks and months that followed, we began the long and laborious journey to rebuild our lives. Many things had changed forever and even I, a young lad, could see that. The “Tuans” were not the almighty forces they had made themselves out to be. The superiority with which they had conducted themselves now seemed laughable. Many white folks escaped violence at the hands of the Japanese by the skin of their teeth, helped by the kindness of their local staff. My father, for instance, could have refused help to his British boss, but he chose to be gracious.

Shortly after the Japanese Occupation of Southeast Asia officially ended on 12 September 1945, my father and his family made their way back to Kuala Lumpur where he completed his education. He worked for a short while as a stenographer in the attorney-general’s office there before moving to Singapore to train as a teacher, where he met and married my mother in 1958. My father turns 90 in December this year.

Aishwariyaa Ramakanthan is an English and Social Studies teacher. She graduated with a bachelor’s degree in English from the National University of Singapore and obtained her master’s in history from the University of San Diego, California. She also has a post-graduate Diploma in Education from the Institute of Education, Singapore.

Aishwariyaa Ramakanthan is an English and Social Studies teacher. She graduated with a bachelor’s degree in English from the National University of Singapore and obtained her master’s in history from the University of San Diego, California. She also has a post-graduate Diploma in Education from the Institute of Education, Singapore.