Daguerreotypes to Dry plates: Photography in 19th-century Singapore

The oldest known photographs of Singapore were taken by Europeans in the early 1840s. Janice Loo charts the rise of commercial photography in the former British colony.

Photography is the “method of recording the image of an object through the action of light on a light-sensitive material”.1 Derived from the Greek words photos (“light”) and graphein (“to draw”), photography was invented by combining the age-old principles of the camera obscura (“dark room” in Latin2) and the discovery in the 1700s that certain chemicals turned dark when exposed to light.

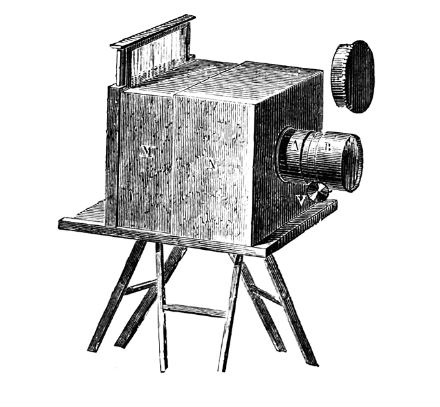

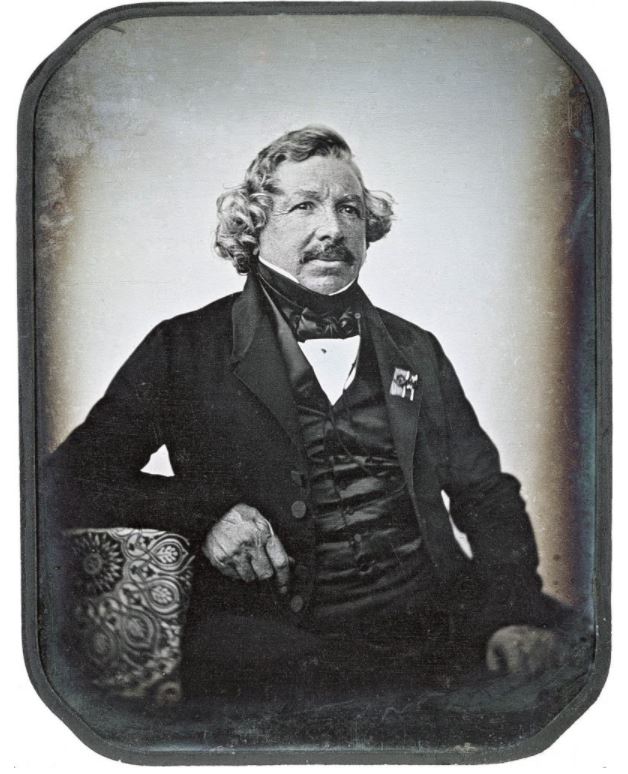

However, it was not until 1839 that the daguerreotype, the earliest practical method of making permanent images with a camera, was introduced. Named after its French inventor Louis Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, the daguerreotype spread across the world, and soon found its way to Singapore.

A Marvellous Invention

The earliest known description of photography here is found in the Hikayat Abdullah (Stories of Abdullah), the memoir of Malay scholar Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir (better known as Munsyi Abdullah3), first published in 1849 by the Mission Press in Singapore.

In the Hikayat, Abdullah recounted how Reverend Benjamin Keasberry, a Protestant missionary whom he was teaching the Malay language to, had shown him “an ingenious device, a copper sheet about a foot long by a little over six inches wide, on which was a picture or imprint of the whole Settlement of Singapore in detail […] exactly reproduced”.4 What Abdullah saw was a daguerreotype, an image captured on a polished silver-coated copper plate.

“Sir, what is this marvel and who made it?”, the astonished Munsyi had asked.5

“This is the new invention of the white man,” replied the Reverend. “There is a doctor6 on board an American warship here who has with him an apparatus for making these pictures. I cannot explain it to you for I have never seen one before. But the doctor has promised me that he will show me how it works next Monday.”

Abdullah’s meeting with the said doctor took place around 1841 – just two years after the daguerreotype was invented and introduced to the world.7

Although it was Abdullah’s first encounter with the technology, he was able to describe in impressive detail the equipment and the manner in which it should be used: how the doctor buffed and sensitised the plate, and then exposed it in the camera to create a latent image that subsequently emerged in a waft of mercury fumes. The resulting photograph of Singapore town taken from Government Hill (now Fort Canning) was, in Abdullah’s words, “without deviation even by so much as the breadth of a hair”.8

Indeed, the daguerreotype brought a degree of sharpness and realism to picture-making that was unparalleled in its time. However, the technology had its drawbacks: the black and white image would become laterally reversed and, as it was composed of tiny particles deposited on the plate’s polished silver surface, it could be marred by the slightest touch. Due to its metal base, the daguerreotype was also highly susceptible to tarnishing. To protect the image, daguerreotypes were typically displayed under glass within a frame or case.

The Oldest View

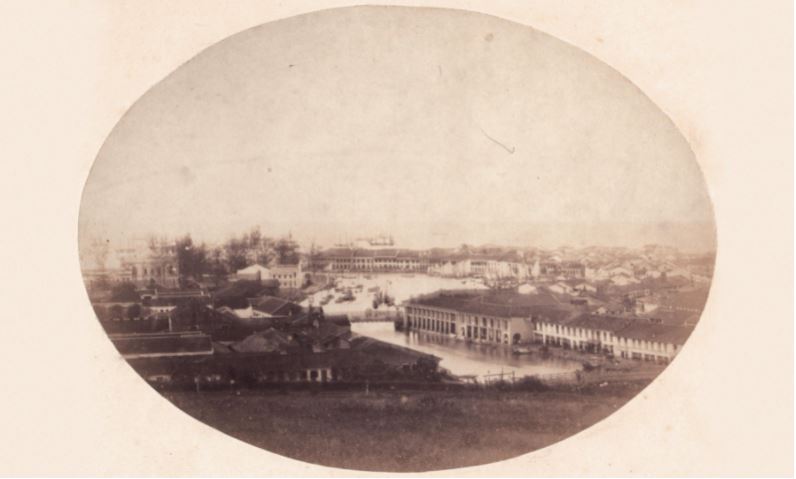

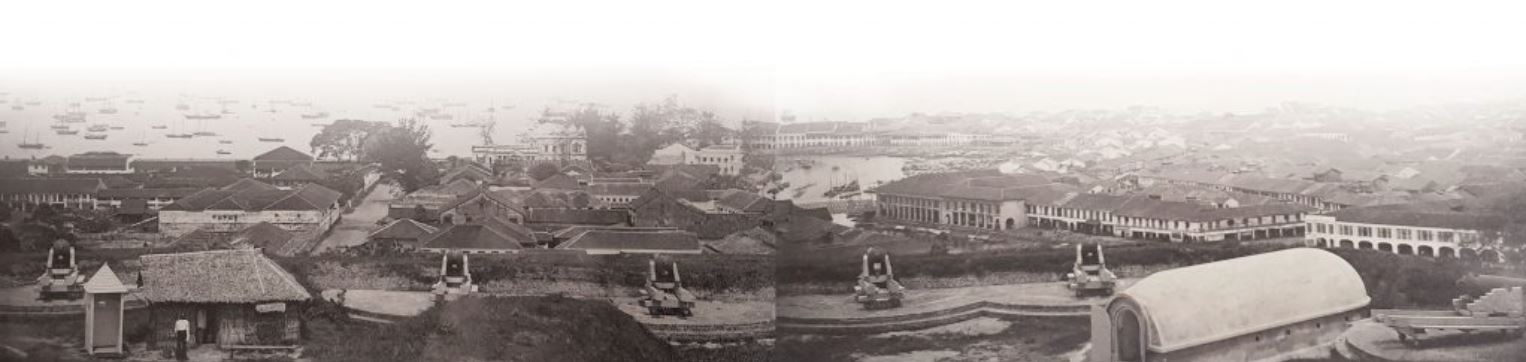

Since the fate of the images mentioned in the Hikayat Abdullah remains unknown, the daguerreotypes produced in 1844 by Alphonse-Eugène-Jules Itier, a French customs inspector, are considered the oldest surviving photographic views of Singapore.

Itier travelled through this part of the world en route to China as part of a French trade mission led by French ambassador Théodose de Lagrené.9 The delegation arrived in Singapore on 3 July 1844, staying here for two weeks before departing on 16 July. The sights and sounds of the bustling port left a deep impression on Itier, who took pictures to show the remarkable development of the port settlement within a mere two decades of its founding in 1819.

One of the four known daguerreotypes of Singapore taken by Itier currently resides in the collection of the National Museum of Singapore. It shows a panoramic view of shophouses and godowns lining the banks of the Singapore River at Boat Quay, and was likely to have been taken on 4 July when Itier visited the residence of then governor, William J. Butterworth, on Government Hill.

Due to its age, the picture appears hazy and dull. But what might it have looked like in its time?

Held in hand and viewed up close, the townscape would have appeared ethereal as it lay suspended on a mirror-like surface, whose reflective properties lent visual depth to the scene. The image also alternated between positive and negative depending on the angle in which it was held and observed. Recalling Munsyi’s reaction, one could imagine how these unique characteristics would have enthralled many a first-time viewer. The other three daguerreotypes by Itier feature the entrance to Thian Hock Keng temple on Telok Ayer Street, a horse cart on a street, and two Malay carriage handlers.10

Itier was a keen amateur scientist and daguerreotypist. His skills became invaluable during the long voyage as a confidential aspect of the mission was the exploration of possible locations for setting up a French port in the China Sea. The delegation stayed at the London Hotel whose proprietor, Gaston Dutronquoy, ran a photographic studio offering daguerreotype portraits in the same building.11

A Hotelier’s Sideline

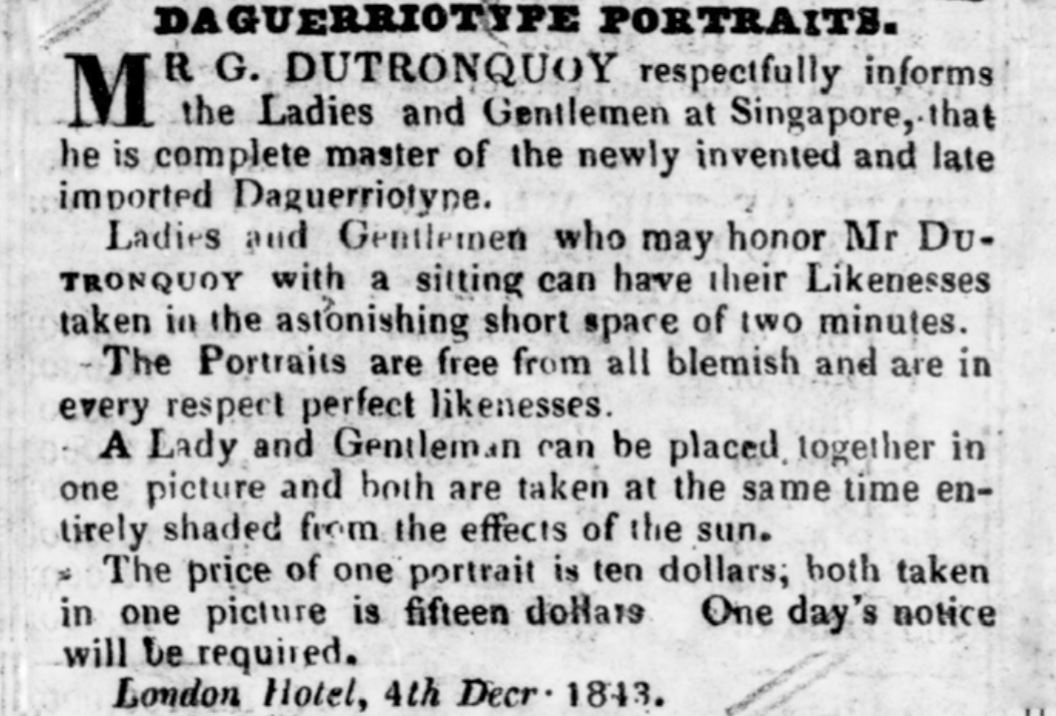

Dutronquoy first advertised himself as a painter in March 1839. Two months later, he opened the London Hotel at Commercial Square (now Raffles Place). In 1841, the hotel shifted to the former residence of architect and Superintendent of Public Works, George D. Coleman.12 It was here that the enterprising Dutronquoy started the town’s first commercial photographic studio in 1843, offering daguerreotype portraits at $10 each, or $15 for two persons in one picture.

To attract prospective customers, Dutronquoy proclaimed his mastery of the daguerreotype process, asserting that his portraits would be “taken in the astonishing short space of two minutes […] free from all blemish and […] in every respect perfect likenesses”.13 Given that the subjects had to hold absolutely still to obtain a sharp picture, a two-minute exposure (painfully slow by today’s instant imaging standards) was a selling point at the time.14

In the absence of surviving works, it is difficult to say how successful Dutronquoy was as a daguerreotypist. There was not enough demand to maintain a fulltime photography business, yet Dutronquoy was sufficiently motivated to keep up with advances in the technology, and made efforts to grow his clientele.

For example, an advertisement in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser on 16 January 1845 announced that Dutronquoy had acquired a new “D’arguerothipe Press”, and portraits could be made at the studio for $6 each, or if one prefers, in the comfort of one’s own home for double that price. The London Hotel, along with his photographic studio, had by then relocated to the corner of High Street and the Esplanade (Padang), with the studio open only in the mornings between 8.30 and 10 am.15

Another advertisement in The Straits Times three years later publicised the availability of “likenesses, in colours, taken in four seconds”.16 This is interesting for two reasons. First, it indicates that Dutronquoy practised hand-colouring, which involved the careful application of pigments to a monochrome portrait for aesthetic purposes and to simulate real-life colours. Like many of his counterparts in the West, Dutronquoy might have enhanced the jewellery pieces worn by the subjects with gold-coloured paint, added a touch of pink to their cheeks, or tinted the background with blue to mimic the colour of the sky.17

Second, the ability to make a portrait in just four seconds indicated that Dutronquoy kept abreast with advances in photographic technology that tackled the problem of lengthy exposures. Interested customers who wanted their portraits taken had to give him a day’s notice and were instructed to wear dark clothing. His studio was only open for two hours in the morning: between 7.30 and 9.30 am from Monday to Saturday.

Dutronquoy’s daguerreotype business was likely not a money spinner and he fared better in hospitality, opening a branch of the London Hotel at New Harbour (today’s Keppel Harbour) in 1851. Alas, Singapore’s first resident commercial photographer met with a mysterious, if tragic, end. During a prospecting trip to the Malay Peninsula in the mid-1850s, Dutronquoy was feared murdered after he suddenly disappeared.18 A 1858 notice in The Straits Times announced the insolvency of his estate.

After Dutronquoy’s departure, Singapore was not to see another resident professional photographer for some time. The 1850s was a period of sporadic photographic activity owing to the fleeting presence of travelling daguerreotypists who passed through Singapore: H. Husband in 1853, C. Duban in 1854, Saurman in 1855, and J. Newman from 1856 to 1857. They stayed only as long as there were enough customers before moving on to other places.

The limited commercial success of daguerreotypes in Singapore could be attributed to several factors: the small consumer population, the relative high price of commissioning a portrait and the capital required to run a professional studio. Human vanity also came into play; for those who were used to seeing a more flattering version of themselves rendered in painting, the stark precision of the daguerreotype could be an unpleasant reality check.

A New Method

The daguerreotype was eventually superseded by the wet-plate collodion process, which produced a negative image on a glass plate. Invented in 1851 by the British amateur photographer Frederick Scott Archer, the wet-plate process was the most popular photographic method from the mid-1850s to the 1880s.

The process of creating a wet-plate negative called for ample preparation time, skill and speed. The photographer had to work swiftly to coat, expose and develop the glass plate while the light-sensitive collodion on its surface was still damp (hence the “wet-plate” process).19 This meant that a photographer working away from the comfort of his studio would have had to carry all the materials and equipment necessary to set up a portable darkroom on location.

Although cumbersome, the wet-plate technique was inexpensive and, once mastered, could create detailed images of a consistent quality. Moreover, unlike the single irreproducible image created by the daguerreotype process, an unlimited number of positive prints could be produced from a single wet-plate negative – setting the stage for the rise of commercial photography. These prints were typically made on albumen paper.

Edward A. Edgerton, a former lawyer from America, is credited for introducing the wet-plate technique to Singapore in 1858. Edgerton first advertised his services in February that year, providing photographs on glass or paper by a process “never before introduced here, being much superior to the reversed and mirror-like metallic plates of the daguerreotype”.20

Initially operating from his residence on Stamford Road, Edgerton entered into a partnership with a certain Alfeld, and the studio relocated across the road to 3 Armenian Street by May 1858. A year later, however, Edgerton moved on to run another studio at Commercial Square. By 1861, he was no longer in the trade and had become editor of the Singapore Review and Monthly Magazine. Unfortunately, as far as we know, none of Edgerton’s works have survived the passage of time.

Pioneering Commercial Studios

Other photographers soon set up shop in the wake of Edgerton’s short-lived venture. These include Thomas Heritage, formerly from London, who came to Singapore after completing work in Penang. He opened his studio at 3 Queen Street on 20 August 1860, and is listed in the Straits Directory of 1861 and 1862; French photographer O. Regnier, whose studio at Hotel l’Esperance is listed in the Straits Directory of 1862; and Lee Yuk at Teluk (Telok) Ayer Street, who is also listed in the 1862 Straits Directory. These studios operated in Singapore for a short period only.

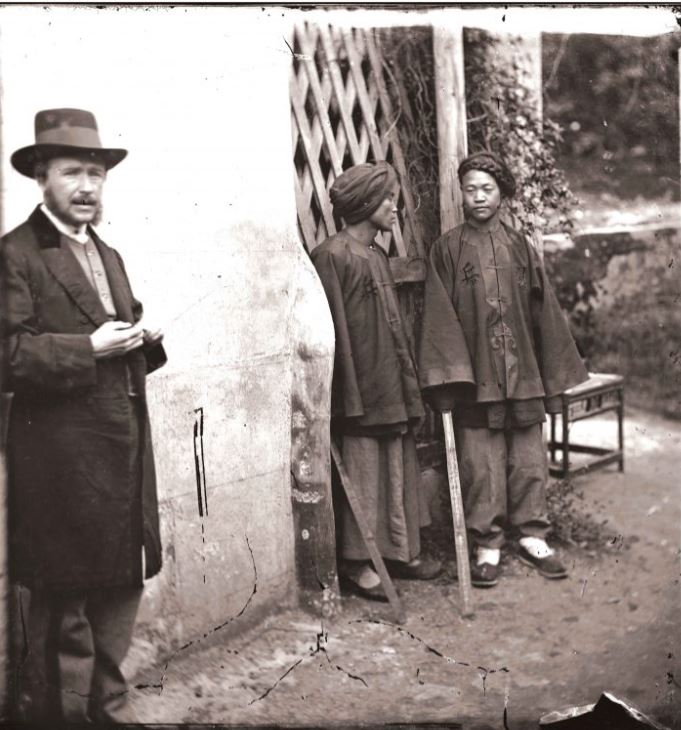

For a brief time, Singapore was also home to John Thomson, who later gained recognition for his extensive photographic documentation of China in the 1870s, and is feted as one of the most accomplished travel photographers of the 19th century. A Scotsman, Thomson came to Singapore in June 1862 to join his older brother, William, who had arrived about two years prior and ran a ship chandlery business on Battery Road.21

The two formed a partnership called Thomson Brothers. With Singapore as his base, the younger Thomson spent considerable time travelling in the region, building up an impressive portfolio of images of Siam (Thailand), Cambodia and Vietnam.22 He moved to Hong Kong in 1868 to begin the ambitious project of photographing China, while William continued the business in Singapore until 1870.23

One of John Thomson’s significant works on Singapore is the four-part panorama of the Singapore River that he produced in the early 1860s. Using the wet-plate collodion method, Thomson created four separate exposures that could be aligned to form a single panorama, with each retaining its appeal as an individual photograph.

A contemporary of the Thomson Brothers was Sachtler & Co., which was most likely established in 1863 and came to dominate commercial photography in Singapore for a decade.24 The identity of Sachtler & Co.’s original proprietor remains a mystery. By July 1864, however, the business had been taken over by a German, August Sachtler, in partnership with Kristen Feilberg. Sachtler was a telegrapher by profession, but his exposure to photography during an assignment to Japan in 1860 led to a change in career.25

Located on High Street near the Court House, Sachtler & Co. offered photography services with the images mounted on a wide variety of the latest frames and albums imported from England, as well as a ready selection of Singapore-made photographs. In 1865, a branch studio, Sachtler & Feilberg (a partnership between Hermann Sachtler, presumably August’s brother, and Feilberg), opened in Penang. Feilberg went on to start his own practice in 1867, and Hermann Sachtler returned to Singapore by 1869.

That year, it was reported that Hermann had met with a bad accident while taking photographs from the roof of the French Roman Catholic Church (present-day Cathedral of the Good Shepherd). While adjusting his camera, Hermann lost his footing and fell from a height of some 20 to 25 metres, fracturing his skull and arm, yet miraculously surviving the ordeal.

In 1871, Sachtler & Co. relocated to Battery Road before returning to High Street in 1874, reopening as Sachtler’s Photographic Rooms at No. 88, opposite the Hotel d’Europe. By then, the firm was supplying an extensive range of photographs taken around the region, including “views and types of Borneo, Java, Sumatra, Saigon, Siam, Burmah, and Straits Settlements”.26 Sachtler & Co. ceased business shortly after; in June 1874, its stock of negatives and equipment was acquired by another photographic studio, Carter & Co.

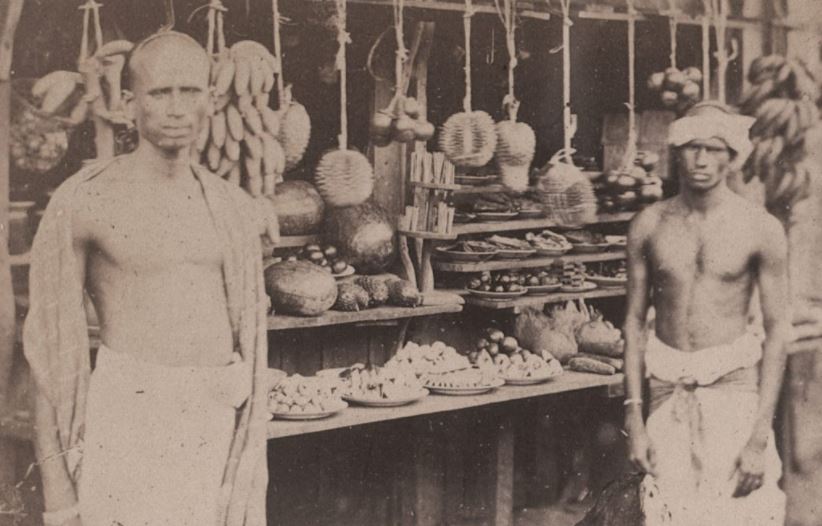

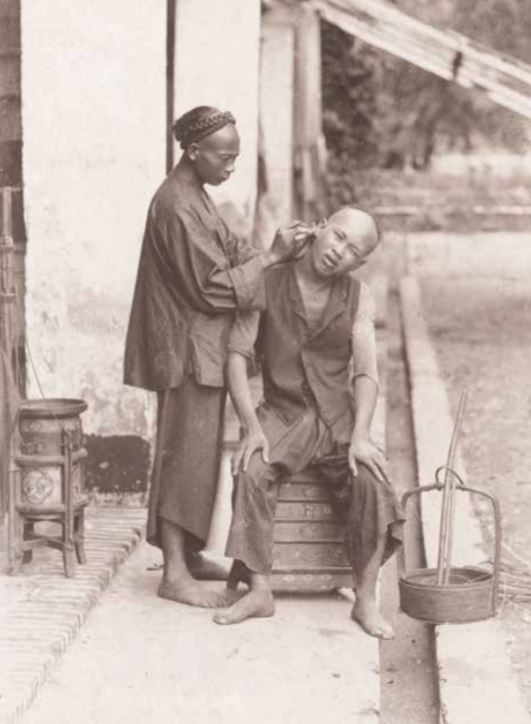

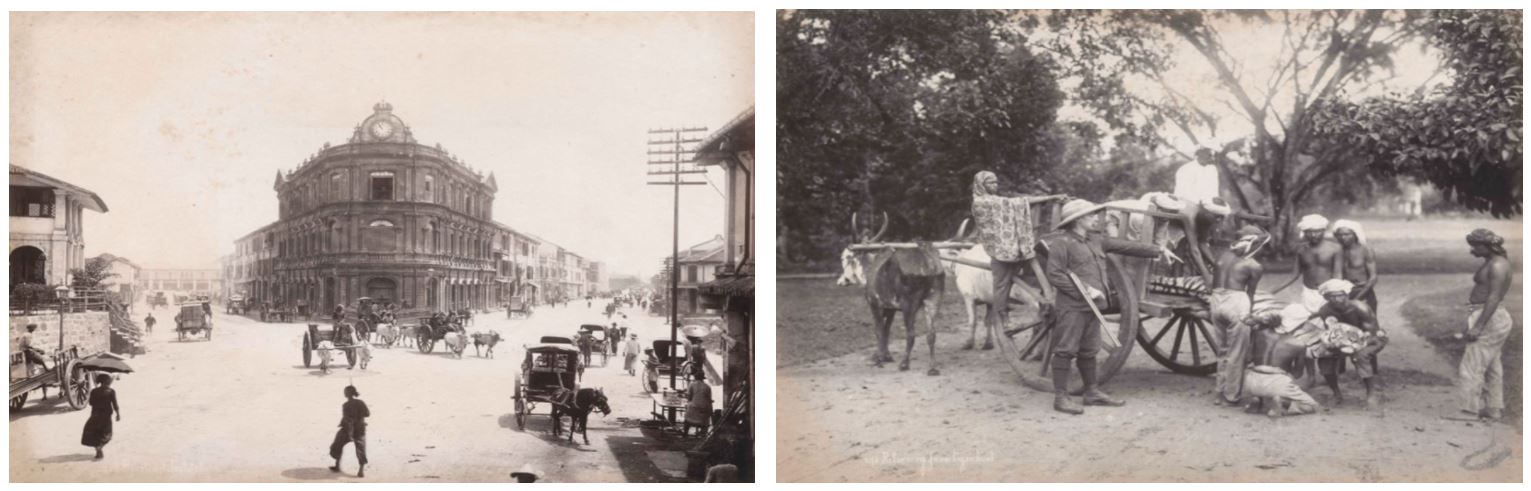

Held in the National Library of Singapore is an album by Sachtler & Co. titled Views and Types of Singapore, 1863, containing 40 albumen prints that make up the oldest photographic material in the library’s collection. As the title indicates, the album features picturesque scenes (“views”) of the settlement and portraits of its diverse inhabitants (ethnographic “types”).

Bearing in mind the inconvenience of the wet-plate process, it is no surprise that photographs during this period tended to be produced in the studio, or if taken outdoors, were of stationary or posed subjects. Portraiture, landscape and architectural views were the norm, as the album amply demonstrates. These were the stock-in-trade of European photographic studios, and served as a visual representation of the exotic “Far East” for a predominantly Western audience.

The Boom and Bust Years

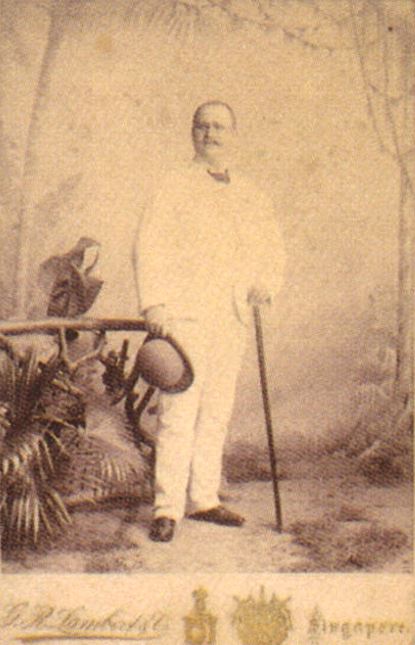

The closure of Sachtler & Co. left a gap that another photographic studio, G.R. Lambert & Co., rose to fill and in fact surpass. G.R. Lambert & Co. was established at 1 High Street by Gustave Richard Lambert from Dresden, Germany, on 10 April 1867. The first mention of the studio was in an advertisement placed in The Singapore Daily Times on 11 April 1867.27 The next reference to Lambert’s presence in Singapore appeared in the 19 May 1877 edition of The Straits Times, announcing his return from Europe, and the opening of his new studio at 30 Orchard Road.28

It is difficult to assess Lambert’s own photographic contributions due to the scarcity of surviving works from the period when he managed the firm in the late 1870s until the mid-1880s, coupled with his sporadic presence in Singapore. Lambert travelled to Bangkok in late 1879 to expand the firm’s photographic collection, returning in February 1880. It was during this visit that G.R. Lambert & Co. was appointed the official photographer to the King of Siam. With Lambert away for much of 1881 and 1882, the firm was overseen by its managing partner, J.C. Van Es. By 1882, G.R. Lambert & Co. had also become the appointed official photographer to the Sultan of Johor. The studio shifted to 430 Orchard Road by 1883.

Lambert returned to Europe by 1887, leaving the business in the capable hands of a fellow German, Alexander Koch, who joined the firm as an assistant in 1884, and was made partner in 1886. The studio moved to 186 Orchard Road in 1886. Koch would prove to be the man behind the stellar rise of the firm. Over the next two decades, G.R. Lambert & Co. expanded its business, opening another office at Gresham House on Battery Road in 1893, and at various times maintained overseas branches in Sumatra, Bangkok and Kuala Lumpur.

This period coincided with the widespread adoption of the gelatin dry-plate process – invented in 1871 – which enhanced photographic production. Unlike the wet-plate technique, the glass plate could now be coated, dried and stored for later use, and need not be developed immediately upon exposure. Compared to collodion, the gelatin emulsion was more sensitive, opening up the possibility of capturing motion. Such technical breakthroughs helped expand the photographer’s repertoire to include fast-moving human figures and objects. Imagine a photograph of a street scene where pedestrians and traffic no longer disappear into a wispy blur, but have a distinct presence, their movements frozen in time.

The advent of mass travel at the turn of the 19th century brought new opportunities. G.R. Lambert & Co. successfully capitalised on the lucrative demand for photographs – and later on, picture postcards – as tourist souvenirs. In 1897, the firm produced the first picture postcard of Singapore, and by 1908 reportedly sold “about a quarter of a million cards a year”.29

By the early 20th century, G.R. Lambert & Co. was lauded as “the leading photographic artists of Singapore [with] a high reputation for artistic portraiture”. It had “one of the finest collections [of landscapes] in the East, comprising about three thousand subjects, relating to Siam, Singapore, Borneo, Malaya, and China”.30

Although advances in photography made G.R. Lambert & Co. the most prolific studio, technology also came to place the tools of a photographer’s trade in the hands of laymen. The growth of amateur photography chipped away at the firm’s revenue, and perhaps as a sign of things to come, G.R. Lambert & Co. gave up its studio at 186 Orchard Road in 1902, downsizing to smaller premises at 3A Orchard Road. Koch retired in 1905, and the firm’s fortunes continued to decline in subsequent years, with its picture postcard trade disrupted by the outbreak of World War I (1914–18) in Europe. Ironically, it was the popularity of picture postcards that had cannibalised its sale of photographic prints in the first place.

Unable to keep up with the times, G.R. Lambert & Co. eventually closed in 1918. It was by no means the only one to suffer as other European firms in Singapore also succumbed to the vagaries of the changing business environment.

An Incomplete Picture

The story thus far constitutes a series of snapshots, a quick survey of the milestones and key movers in the history of photography in 19th-century Singapore. It is, unsurprisingly, a narrative dominated by European photographic studios, which left documentary evidence of their presence, and whose extensive work make up some of the most valuable early visual records of the settlement.

As these European studios faded from the scene in the early 20th century, it paved the way for Asian players to take their place in the interwar period. To give a sense of the new situation, the census of 1921 counted 171 photographers comprising 109 Chinese, 52 “others” (Japanese, Siamese, Sinhalese, Arabs or Asiatic Jews), six Malays, three Indians and only one European.

Some research has been done and continue to be carried out on Asian photographers, for example, the Lee Brothers Studio, a family-owned photographic enterprise run by Lee King Yan and Lee Poh Yan, at the corner of Hill Street and Loke Yew Street. There are many more photographers whose names await to be uncovered and their stories told.

Janice Loo is a Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include collection management and content development as well as research and reference assistance on topics relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

Janice Loo is a Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include collection management and content development as well as research and reference assistance on topics relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

NOTES

-

Beaumont, N. et al. (2019, January 25). History of photography. Retrieved from Encyclopaedia Britannica website. ↩

-

Refers to the natural optical phenomenon where light reflecting off an illuminated scene and passing through a tiny hole into a darkened room would form an exact, but inverted, image of that scene on the wall opposite. The phenomenon was described in as early as the 5th century BCE. ↩

-

Munsyi Abdullah taught Malay to many British administrators, including Stamford Raffles, missionaries and European traders, hence the epithet Munsyi which means “teacher”. ↩

-

Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir. (2009). The Hikayat Abdullah (p. 295). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: The Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. (Call no.: RSEA 959.5 ABD). ↩

-

Abdullah’s conversation with the doctor quoted from Abdullah, 2009, pp. 295–296. ↩

-

The doctor in question might have been Dr Wright, a junior doctor on board the American ship, USS Constellation, which docked in Singapore from 4 November 1841 to 5 February 1842. According to a private letter from Mrs Maria Balestier (wife of Joseph Balestier, the first American consul in Singapore) to her sister, the doctor produced a “daguerreotype drawing” of the Balestiers’ home in the Rochor area. See Hale, R. (2016). The Balestiers: The first American residents of Singapore (p. 156). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 959.57030922 HAL). ↩

-

Falconer, J. (1987). A vision of the past: A history of early photography in Singapore and Malaya (p. 9). Singapore: Times Editions. (Call no.: RSING 779.995957 FAL). ↩

-

The Lagrené mission, as it came to be known, resulted in the Treaty of Whampoa signed on 24 October 1844, which secured for France the same privileges extended to Britain. See Massot, G. (2015, November). Jules Itier and the Lagrené Mission. History of Photography, 39 (4), 319–347, p. 320. (Call no.: RCLOS 770.92 MAS). ↩

-

According to Itier’s published account of the trip, Journal d’un Voyage en Chine en 1843, 1844, 1845, 1846, the daguerreotype of Thian Hock Keng was made on 6 July 1844, which places it as the earliest dated photograph of Asia. See Massot, Nov 2015, pp. 323, 346. ↩

-

The street on which the house stood was later named after Coleman. Coleman’s house was located at 3 Coleman Street where the Peninsula Shopping Centre now stands. See London Hotel. (1842, January 13). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Daguerriotype portraits. (1843, December 7). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hirsch, R. (2000). Seizing the light: A history of photography (p. 32). Boston: McGraw-Hill. (Call no.: RART 770.9 HIR). Depending on light conditions, exposures ranged from a few minutes to as long as half an hour, which explains the often-solemn expressions and stiff postures in early portraits. ↩

-

Notice. (1844, 22 February). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 1; Notice. (1845, January 16). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. Mornings were more conducive for taking photographs as temperatures were still cool, and daylight would be sufficient without being overpowering. ↩

-

Daguerreotype. (1848, October 21). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lavédrine, B. (2009). Photographs of the past: Process and preservation (pp. 30–31). Los Angeles, California: The Getty Conservation Institute. (Not available in NLB holdings); See Claudet, L. (2008). Colouring by hand. In J. Hannavy (Ed.)., Encyclopedia of nineteenth-century photography Vol 1 (pp. 322–323). New York: Routledge. Retrieved from Google Books. A practical method for colour photography was not invented until the Lumiére brothers’ autochrome process in 1904. ↩

-

Buckley, C.B. (1984). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore 1819–1867 (p. 745). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 BUC). However, another source suggests that Dutronquoy might have passed away sometime in January 1872 in Kobe, Japan. See Massot, Nov 2015, p. 323. ↩

-

Hirsch, 2000, p. 72. Collodion was made by dissolving gun cotton in ether and alcohol, and then adding potassium iodide. The resultant viscous mixture is applied evenly to a glass plate, which is immersed into a bath of silver nitrate to produce light-sensitive silver iodide. ↩

-

Portraits & views. (1858, February 13). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Notice (1862, June 14). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; White, S. (1989). John Thomson: A window to the orient (p. 9). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. (Call no.: RART 770.92 WHI). William was also a photographer in the partnership of Sack and Thomson, Beach Road (listed in the 1861 Straits Directory). The partnership was brief and William was listed on his own as a photographic artist in the following year’s directory. ↩

-

White, 1985, pp. 9–17. John Thomson published an account of his time in Asia. See Thomson, J. (1875). The Straits of Malacca, Indo-China and China, or Ten years’ travels, adventures and residence abroad. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low, & Searle. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

The firm Thomson Brothers is listed in the Straits Directory for the years 1863 through to 1870. Balmer, J. (1993). Introduction. In J. Thomson (1993). The Straits of Malacca, Siam and Indo-China: Travels and adventures of a nineteenth-century photographer (pp. xiv, xiii). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 915.9 THO-[TRA]). ↩

-

Sachtler & Co. was first listed in the Straits Directory for 1864, and was likely to have been founded the year before. See Falconer, 1987, p. 27. ↩

-

Dobson, S. (2009, May). The Prussian expedition to Japan and its photographic activity in Nagasaki in 1861. Old Photography Study, 3, pp. 28–29. Retrieved from Nagasaki University’s Academic Output website. ↩

-

Notice. (1874, June 6). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Bautze, J.K. (2016). Unseen Siam: Early photography 1860–1910 (p. 183). Bangkok: River Books. (Call no.: RSEA 959.3034 BAU). ↩

-

Notice. (1877, May 19). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. Lambert was first listed in the Straits Calendar and Directory for 1868, and was not to appear again until 1878. ↩

-

Wright, A., & Cartwright, H.A. (Eds.). (1908). Twentieth century impressions of British Malaya: its history, people, commerce, industries, and resources (p. 705). London: Lloyd’s Greater Britain Publishing Company. (Microfilm: NL16084); Cheah, J.S. (2006). Singapore: 500 early postcards (pp. 9–10, 12). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING 769.56609595). ↩

-

Wright & Cartwright, 1908, pp. 702, 705. ↩