On Paper: Singapore Before 1867

Paintings by John Turnbull Thomson, poems in Jawi script, an early 19th-century map of Asia and a Russian traveller’s tale of Singapore are some of the paper artefacts featured in the National Library’s latest exhibition, “On Paper: Singapore Before 1867”.

J.T. Thomson’s Paintings

John Turnbull Thomson is best known for his role as Government Surveyor of the Straits Settlements as well as his design and engineering work on several key early buildings in Singapore. What is less well known is that Thomson, a self-trained artist, also made invaluable contributions to the pictorial documentation of Singapore through his paintings.

The four vibrant watercolour works featured here, which exemplify Thomson’s unique artistic approach and style, vividly capture the state of Singapore’s built landscape in the mid-1840s. They also reflect the cultural diversity of the communities and people who made their home on the island.

The 1847 painting, “Chinese Temple to the Queen of Heaven”, depicts the Thian Hock Keng temple on Telok Ayer Street. The temple began as a shrine erected around 1820–21 by Chinese immigrants from Fujian province, China, and was dedicated to Mazu, Mother of the Heavenly Sages and patron goddess of sailors. The Chinese migrants would make offerings at the shrine in gratitude for their safe passages to and from China.

Between 1839 and 1842, the shrine was transformed into Thian Hock Keng temple after massive construction works. The project was spearheaded by Chinese merchant Tan Tock Seng, who also funded a large portion of the construction costs. Many of the builders and artisans were brought in directly from Fujian.

Today, Thian Hock Keng remains the most important temple of Singapore’s Hokkien community. Thomson’s painting shows its facade, which has largely been preserved. One feature that stands out is the seafront, which is visible in the painting’s foreground. Telok Ayer Street used to run along the coast, before land reclamation pushed the road inland.

Thomson’s painting titled “Muslim Mosque in Campong Glam” (1846) is of special historical interest as it depicts the Masjid Sultan (Sultan Mosque) in Kampong Glam before it was replaced with the present structure we are familiar with. The earlier iteration of Sultan Mosque was a single-storey brick building that featured a tiered pyramidal roof commonly found in traditional Southeast Asian religious architecture.

It was built between 1824 and 1826 by Sultan Husain, whom Stamford Raffles had installed as the Sultan of Johor in order for the 1819 Treaty of Friendship and Alliance to be signed (the treaty allowed the British East India Company, or EIC, to set up a trading post on Singapore). Land for the mosque was allocated by Raffles, who also contributed 3,000 Spanish dollars on behalf of the EIC towards its construction.

This building served the Muslim community in Singapore for more than a hundred years before it was torn down in 1932 to make way for a new mosque, designed by the architectural firm Swan and Maclaren in the Indo-Saracenic style, complete with onion domes and minarets. Masjid Sultan is a well-known landmark in Kampong Glam today.

Another of Thomson’s paintings, “Hindoo Pagoda and (Chulia) Mosque” (1846), depicts two religious buildings along South Bridge Road. On the left is Sri Mariamman Temple, the oldest Hindu temple in Singapore. The structure shown in the painting, with its three-tiered gopuram (pyramidal entrance tower), was constructed in 1844 – by craftsmen and former Indian convicts from Madras – replacing a wood-and-attap structure built in 1827 by the Tamil pioneer Naraina Pillai.

From its inception, the Sri Mariamman Temple has played a key role in Singapore’s Hindu community, serving not only as a place of worship, but also as a refuge for newly arrived immigrants from India seeking accommodation and employment. While the temple compound has remained largely unchanged since the 1880s, the tower was replaced in 1925 with the elaborately decorated five-tiered structure that stands today.

On the right of the painting is Jamae Mosque (Masjid Jamae), which was completed in 1833 to replace the original wood-and-attap mosque built by the Chulia (Tamil Muslim) community, led by Anser Saib, in the late 1820s. Today, the mosque’s distinctive twin minarets continue to be a landmark on South Bridge Road, but the lush greenery surrounding the temple and its spacious frontage seen in Thomson’s painting have given way to shophouses and a busy vehicular thoroughfare.

Thomson’s works also include sweeping views of Singapore from various vantage points. In his 1846 painting, titled “Singapore Town from the Government Hill Looking Southeast”, the viewer is positioned on what is now Fort Canning Hill, overlooking the Singapore River. Densely built shophouses and godowns can be seen along the river at Boat Quay, while a number of expansive bungalows, occupied mostly by Europeans, are found by the seafront north of the river.

In his first book, Some Glimpses into Life in the Far East, published in 1864, Thomson remarked on the stark contrast between the two areas:

“The European part of the town was studded with handsome mansions and villas of the merchants and officials. The Chinese part of the town was compactly built upon, and resounded with busy traffic. In the Chinese quarter fires frequently broke out, spreading devastation into hundreds of families.”1

Taken together, Thomson’s sketches and paintings serve as an invaluable visual record of 19th-century Singapore. As a surveyor and engineer by training, Thomson was able to bring both a critical eye and a different perspective to his art.

– Georgina Wong

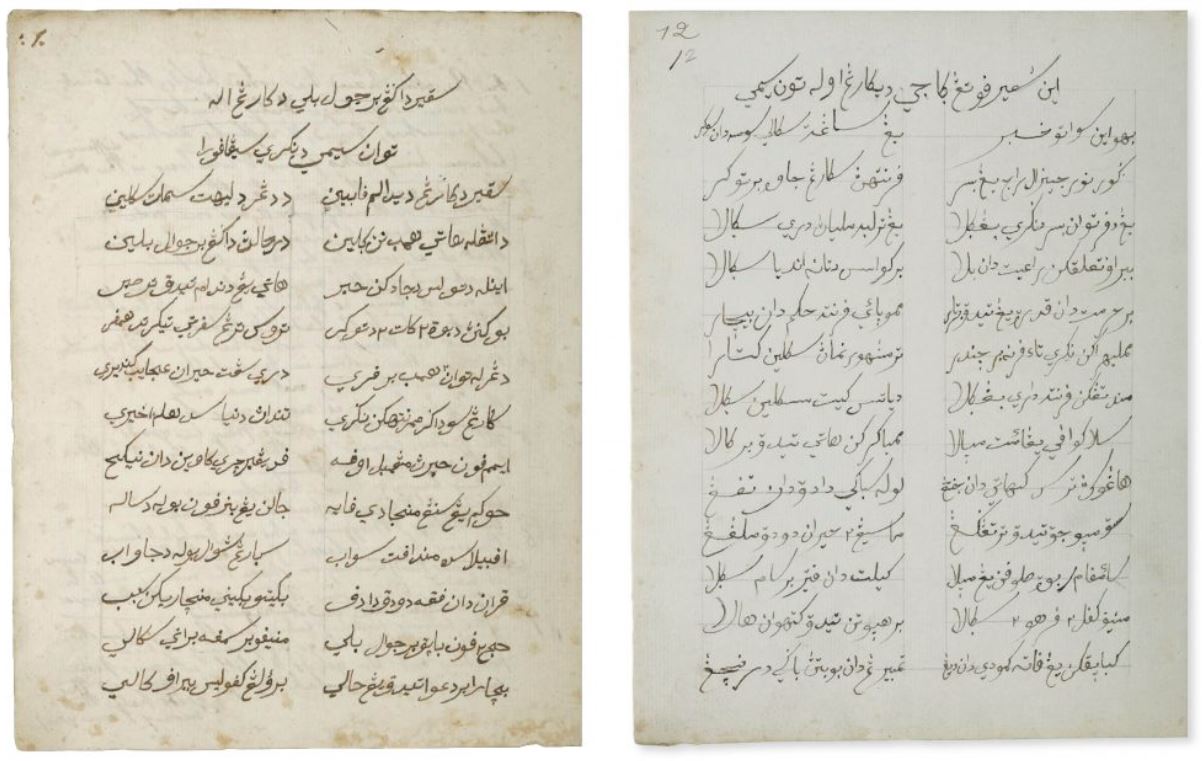

Syair Dagang Berjual Beli and Syair Potong Gaji

Syair Dagang Berjual Beli (On Trading and Selling) and Syair Potong Gaji (On Wage Cuts) are two early 19th-century Malay narratives in the form of the syair (rhymed poem), written by Tuan Simi in Singapore. Tuan Simi was a scribe and translator who had worked for several British personalities, including Stamford Raffles.

These two syair occupy a special place in the Malay literary tradition, bearing testimony to the early years of colonial Singapore, then administered by the British East India Company (EIC; sometimes referred to as the Company). Both syair, composed in the 1830s, may be described as poems of protest, as they give voice to the author’s grievances against the EIC’s practices that affected the lives and wellbeing of local traders and workers.

Syair Dagang Berjual Beli, comprising 56 stanzas, contains Tuan Simi’s observations on trade practices in Singapore. The poem cautions readers to be wary of the unfair practices that were being imposed by the new “Kompeni” (Company) rulers and their network of Chinese and Indian middlemen. Tuan Simi’s realistic style of narration, together with his views on the competing traders who were depriving the indigenous traders of their livelihood, offer the reader an intimate, unvarnished insight into inter-ethnic tensions in colonial society:

“Akan halnya kita Bugis dan Melayu

Harapkan orang putih juga selalu

Hukum bicaranya kelihatan terlalu

Mulut disuap pantat disumbu”2

“Such is the state of us Bugis and Malays

When to the white man we surrender our fates

Of the rulings – it’s true what they say

The hand that gives is that which confiscates”3

The second work, Syair Potong Gaji, comprising 38 stanzas, narrates the misery and frustrations of coolies from Bencoolen (Bengkulu) who worked for the EIC in Singapore. Tuan Simi notes that the coolies suffered economic hardship because of senior managers who neglected their welfare. Profit maximisation had become the EIC’s mantra, to the extent that the work of three men often had to be carried out by one man alone:

“Perasaan hati sangatlah rendah

Kebajikan dibuat tidak berfaedah

Beberapa lamanya bekerja sudah

Harganya dinilai setimbang ludah”4

“We feel very much undignified

Our services rendered unrecognized

Alas a long time we had labored

Like the weight of a spit, it was valued”

These narratives, dissenting in tone and spirit, were naturally considered subversive by the British authorities. They disappeared from local circulation and were eventually forgotten. The two syair were only rediscovered in 1986 by Muhammad Haji Salleh, a Malaysian scholar, when he was conducting research on Malay manuscripts at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris.

The handwritten Jawi texts of the two syair were discovered alongside another, titled Syair Tenku Perabu di Negeri Singapura (On Tenku Perabu of Singapore), which narrates a scandalous affair that allegedly took place in the house of Sultan Husain, between the Sultan’s consort Tenku Perabu and his private secretary, Abdul Kadir. The three syair were compiled, transliterated and published in an anthology, Syair Tantangan Singapura Abad Kesembilan Belas (19th-century Singapore Syair of Remonstrance), by Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Malaysia, in 1994.

Today, these texts are part of Singapore’s history and literary heritage. They provide insights into the early days of modern Singapore, and thus deserve greater recognition and appreciation.

THE FORM OF THE SYAIR

A syair is a narrative poem made up of quatrains, each with an end rhyme. Every line contains about 10 to 12 syllables. Although the origin of this poetic form is still debated today, it is generally attributed to Hamzah Fansuri, a 16th-century Sufi from Sumatra. While it may have been used initially for religious purposes, by the 18th century the syair had become a vehicle for topics as diverse as romantic stories, historical events, advice and so on.5

– Dr Azhar Ibrahim

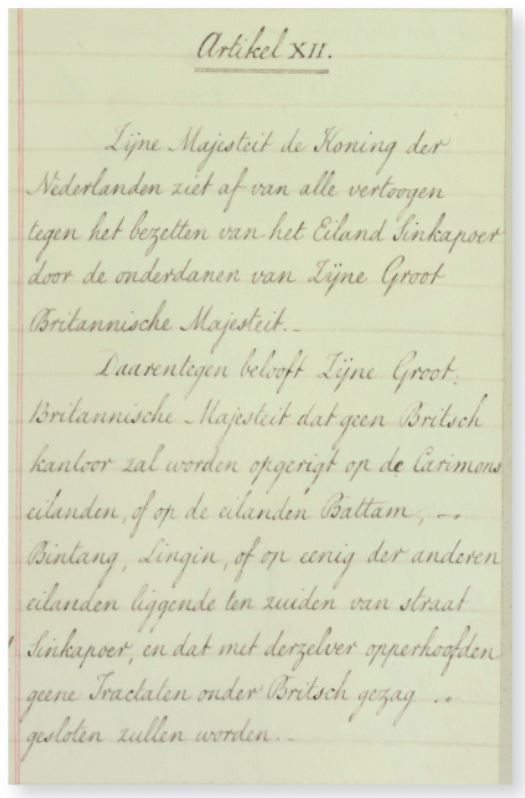

Map of Asia, Used by A.R. Falck in London in 1824

Printed by John Carey in London in the early 19th century, this map of Asia was used during the final negotiations of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty in London between December 1823 and March 1824. It was acquired in 1909 as part of the collection of Anton Reinhard Falck (1777–1843) and is preserved today in the Nationaal Archief in the Netherlands.

A pencil line can be seen running through the Singapore and Melaka straits on the map. This was drawn to illustrate a proposal made by Falck, the Dutch chief negotiator and diplomat. Falck proposed using the line to divide the region into British and Dutch spheres of influence. The story of how this pencil line came about was recounted by Otto Willem Hora Siccama, a relative of Falck’s, who had accompanied the elderly Falck to London as an aide and personal assistant during these negotiations.6

From Falck’s memoirs, as well as Dutch foreign ministry papers relating to the negotiations, it transpires that the scheme to carve up the Southeast Asian region – into a Dutch sphere of influence in the archipelago, and a British one on the Malay Peninsula and the mainland – came from Falck, who had earlier discussed the proposal with the Dutch king, William I. An experienced negotiator and diplomat, Falck hoped to resolve a package of outstanding trade and colonial issues with British Foreign Secretary Lord George Canning by streamlining their patchwork of possessions in Southeast Asia.

After the two spheres of influence were marked out, the British were persuaded to trade off their possessions and concessions on and around the island of Sumatra, namely Bencoolen (Bengkulu) and Billiton (Belitung), which were now in the Dutch sphere of influence, and exchange these for the settlements of Melaka and Singapore on the peninsula.

As a result, certain arrangements in the Lampongs (southern Sumatra) were affected, as was Stamford Raffles’ treaty with Aceh, which effectively became null and void. The spheres, moreover, were to be exclusive to each party, and so the 1824 Anglo-Dutch Treaty implicitly forbade the commerce of independent polities like Aceh with traders from other states in Europe or the Americas, significantly pepper traders from the United States.

In reaching this arrangement, the Dutch would drop their objections to the British occupation of Singapore as well as the presence of the British East India Company’s trading post there, a concession that was captured in Article 12 of the final Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 17 March 1824. The treaty provided the geographical framework for Anglo-Dutch relations for the remainder of the 19th century and arguably beyond, and today forms the foundation of the borders between Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia.

There are two additional observations worth mentioning in the present context. First, in using the Singapore and Melaka straits as a notional dividing line between the exclusive Dutch and British spheres of influence, the Johor-Riau Sultanate would be split in two. The possessions on the peninsula would fall into the British sphere, while the islands excluding Singapore would go to the Dutch. In this way, Sultan Abdul Rahman, who at the time was based in Daik on the island of Lingga, formally lost control of lands on the peninsula, including Singapore. Moreover, Temenggung Abdul Rahman, who resided in Singapore, lost some of the people and lands that were part of his traditional domain, which included Karimun, Batam, Bulan and other islands to the south.

The second observation concerns the course of the pencil line. This starts off at the northwestern coast of Sumatra, around the northern tip of the island, then runs down through the Straits of Melaka past Karimun through the Durian Strait. Thereafter, it turns eastward between Bintan and Lingga before heading through the Karimata Sea towards Borneo. The line makes a slight southerly bend and finally stops off the Borneo coast near Sukadana.

Therefore, according to this initial proposal captured by Falck’s pencil line, Batam, Bulan (together with the islands south thereof) as well as Bintan were originally slated to fall into the British sphere. That would have included the court of the Bugis Yang di-Pertuan Muda, Raja Ja’afar, but not Sultan Abdul Rahman’s court at Daik on Lingga. The termination of the line off the coast of Borneo, moreover, would assume significance in the later decades of the 19th century, when Raja James Brooke established himself on the island that is today the Malaysian state of Sarawak.

– Assoc Prof Peter Borschberg

A Russian Traveller’s Tale of Singapore

Travel literature on Singapore proliferated during the 19th century in tandem with the spread of colonialism and the expansion of trade and missionary activities in the East. As Singapore was a natural transit point along the East-West route, it was a popular port-of-call for many travellers. From diplomatic and scientific expeditionary parties to sightseers lured to the Far East by the opening of the Suez Canal, visitors recorded their impressions of the island in writing, and sometimes through illustrations.

Although these travelogues were naturally coloured by the subjective views and values of their authors, they offer a wealth of information on early Singapore.7

A 19th-century memoir, Ocherki Perom i Karandashom iz Krugosvetnogo Plavaniya v 1857, 1858, 1859 i 1860 godakh (Sketches in Pen and Pencil from a Trip Around the World in the Years 1857, 1858, 1859 and 1860), describes the voyage of the Russian naval clipper Plastun from 1857 to 1860. It stands out among European travel narratives on Singapore as it presents a rare account of early Russia-Singapore relations. Written and illustrated by the doctor on board, Aleksei Vysheslavtsev (1831–88), the memoir also contains some of the earliest views of Singapore executed by a Russian artist.

The book traces the ship’s journey from the Russian port town of Kronstadt to the Atlantic islands, around the Cape of Good Hope, across the Indian Ocean, through the Sunda Strait to Singapore, and then on to Hong Kong, Canton, Formosa, Manchuria and the Russian Pacific Far East, where it inspected the territories that Russia had recently acquired with the signing of the Russian-Chinese Treaty of Aigun in 1858. From there, the ship sailed to Japan, where the Russians spent a year negotiating a treaty with the Japanese, before heading home. Unfortunately, the ship came to an untimely end when it was destroyed by an explosion on board. By a stroke of providence, the author lived to tell his tale as he had transferred to another vessel before disaster struck.8

The Plastun arrived in Singapore in July 1858, where it anchored for a week. In a chapter titled “The Malay Sea”, the author writes a brief history of British colonisation of Singapore and a description of the settlement’s economy, trade and town layout, which was characterised by separate quarters for Europeans, Chinese, Indians and Malays.

A keen observer, Vysheslavtsev detailed various aspects of life in Singapore: street peddlers, Chinese houseboats on the river, an Indian theatre performance, Indian jugglers, and the manners and appearance of the Chinese, Indian and Malay inhabitants. He took an excursion to some of Singapore’s offshore islands and paid a visit to Hoo Ah Kay (1816–80; commonly known as Whampoa), who later became the first Vice Consul to Russia in 1864. Vysheslavtsev’s account was accompanied by four illustrations: the Singapore harbour, Indian jugglers, Chinese inhabitants and two Chinese men beside a bridge.9

Parts of Vysheslavtsev’s travel account first appeared in the magazine Russky Vestnik from 1858 to 1860 under the title “Letters from Clipper Plastun”. The complete work was published by the Russian Naval Ministry in 1862 with 27 lithographed plates redrawn from the author’s original sketches. In response to warm reviews by the Russian audience, who praised it for its fine drawings and literary style, a second edition was issued in 1867 by a major St Petersburg commercial publisher, Mauritius Wolf, with 23 illustrated plates.10

Although Vysheslavtsev’s travelogue achieved critical and popular acclaim in its time, it was invariably compared to and perhaps even overshadowed by Russian novelist Ivan Goncharov’s (1812–91) The Voyage of the Frigate Pallada (1858). Published four years earlier, Goncharov’s book traces a similar journey to the East – with the Russian mission to Japan under Admiral Putyatin (1803–83) from 1852 to 1854. It includes a vivid description of his visit to Singapore in 1853, which has been studied and translated into Chinese, and partially into English. In contrast, there are no known translations in any language of the Singapore portion of Vysheslavtsev’s account.11

By and large, Russia has occupied a marginal place in the scholarship on European expansion in Southeast Asia. However, this is by no means an indication of its lack of commercial ambitions or scientific interest.

Russia actively sought to protect its shipping routes and extend its influence in the region from the early 19th century. From the 1850s, Russian vessels started using Singapore as a provisioning and coaling station. In the 1870s, the Russian anthropologist Nikolai Miklouho-Maclay embarked on a scientific expedition to study the Orang Asli in the Malay Peninsula and his findings were published in the Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society in Singapore.12 In 1881, K.A. Skalkovsky published an account of a Russian trade mission and survey of the Pacific, which included Singapore.13

However, there still remains a paucity of information on relations between Singapore and Russia until a Russian consulate was formally established in Singapore in 1890 and began submitting regular consular reports on bilateral affairs. Given the dearth of literature, the writings of Vysheslavtsev and Goncharov are valuable for their historical research on the interactions between Tsarist Russia and British-controlled Singapore in the longue durée of Russia-Singapore relations.14

– Gracie Lee

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION AND BOOK

The exhibition “On Paper: Singapore Before 1867” takes place at level 10 of the National Library building on Victoria Street. On display are more than 150 paper-based artefacts – comprising official records, diaries and letters, books and manuscripts, maps, drawings and photographs – tracing Singapore’s history from the 17th century to its establishment as a Crown Colony of Britain on 1 April 1867.

The exhibits, drawn from the collections of the National Library and the National Archives of Singapore, as well as from various local and international institutions – Library of Congress, The British Library, Nationaal Archief, Bibliothèque Nationale de France and the National Library of Indonesia, among others – provide a glimpse of Singapore’s documentary heritage as well as the personalities, and social and political forces behind them. Many of the items are shown to the public in Singapore for the first time.

A series of programmes has been organised in conjunction with the exhibition, including guided tours by the curators and public talks. For more information, follow us on Facebook @NationalLibrarySG.

The accompanying book, also called On Paper: Singapore Before 1867, features a small selection of the items being shown at the exhibition, illuminated by essays written by librarians, archivists and scholars.

The book is not for sale but is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 959.9703 ON and SING 959.9703 ON).

NOTES

-

Thomson, J.T. (1865). Some glimpses into life in the Far East (pp. 201–202). London: Richardson & Co. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Muhammad Haji Salleh. (1994). Syair tantangan Singapura abad kesembilan belas (p. 46) Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. (Call no.: Malay RSING S899.230081102 SYA). ↩

-

Frost, M.R., & Balasingamchow, Y.-M. (2009). Singapore: A biography (p. 107). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet & National Museum of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 FRO). ↩

-

Muhammad Haji Salleh, 1994, p. 53. ↩

-

Tan, H. (2018). Tales of the Malay world: Manuscripts and early books (p. 54). Singapore: National Library Board. (Call no.: RSING 499.28 TAL). ↩

-

Letter by Otto Hora Siccama to Minister Elout, dated 26 October 1858, in Cornelis Theodorus Elout. (1865). Bijdragen tot de Geschiedenis der Onderhandelingen met Engeland betreffende de Overzeesche Bezittingen, 1820–1824 getrokken uit de nagelaten papieren (pp. 311–312). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. ↩

-

Teo, M., et al. (1987). Nineteenth-century prints of Singapore (pp. 6–14). Singapore: National Museum. (Call no.: RSING 769.4995957 TEO). ↩

-

Wiswell, E.L. (1983). A Russian traveler’s impressions of Hawaii and Tahiti, 1859–1860. The Hawaiian Journal of History, 17, 76–142. Retrieved from the University of Hawaii’s eVols website; The Wayfarer’s Bookshop. (2017, December). Exploration, travels & voyages: Books, maps & prints including Islamic and Russian items. Retrieved from The Wayfarer’s Bookshop; Bookvica. (n.d.) [Hong Kong & Singapore] Ocherki Perim i Karandashom iz Krugosvetnogo Plavaniya v 1857, 1858, 1859 I 1860 godakh [Sketches in pen and pencil from the circumnavigation in 1857, 1858, 1859 and 1860]. Retrieved from Bookvica; Princeton University. (2018, February 21). Ocherki perom i karandashem iz krugosvietnago plavaniia. Retrieved from Graphic Arts Collection. ↩

-

The Wayfarer’s Bookshop, Dec 2017; Straits Settlements Records (1864), R41, p. 232. (Microfilm no.: NL78); Straits Settlements Records (1864), V41, p. 113. (Microfilm no.: NL119). ↩

-

Wiswell, 1983; The Wayfarer’s Bookshop, Dec 2017; Bookvica (n.d.), Ocherki. ↩

-

Wiswell, 1983; 冈察洛夫著 & 叶予译. (1982). 《巴拉达号三桅战舰》. 哈尔滨: 黑龙江人民出版社. (Call no.: RSEA 910.4 GON); 黄倬汉. (1998). 冈察洛夫笔下的华侨.《东南亚学刊》, 5, 117–126. (Available at the National University of Singapore Chinese Library, Call no.: DS520 DNYXK); Goncharov, I.A. (author) & Wilson, N.W. (trans.). (1965). The voyage of the frigate Pallada. London: Folio Society. (Call no.: RCLOS 910.4 GON-[JSB]); Bojanowska, E.M. (2018). A world of empires: The Russian voyage of the frigate Pallada. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of the Harvard University Press. (Call no.: RSING 910.45 BOJ). ↩

-

Govor, E., & Manickam, S.K. (2017). A Russian in Malaya: Nikolai Miklouho-Maclay’s expedition to the Malay Peninsula and the early anthropology of Orang Asli (pp. 94–117). In C. Skott (Ed.), Interpreting diversity: Europe and the Malay world. Abingdon, Oxon.: Routledge. (Call no.: RSEA 59.51 INT). ↩

-

Bookvica. (n.d.). Vokrug svyeta: Sorok shest tysiach verst po moryu i sushe: Putevye vpechatleniya K. Skalkovskogo. Retrieved from Bookvica website; Snow, K.A. (1998, March). Russian commercial shipping and Singapore, 1905–1916. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 29 (1), 44–62. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Snow, K.A. (1994, September). The Russian consulate in Singapore and British expansion in Southeast Asia. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 25(2), 344–367; Quested, R. (1970, September). Russian interest in Southeast Asia: Outlines and sources 1803–1970. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 1 (2), 48–60. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website; Straits Settlements. (1890, December 5). Government notification no. 672. Straits Settlements Government Gazette (p. 2719). Singapore: Government Printing Office. Retrieved from BookSG; The Russian consul for Singapore. (1890, November 5). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 529. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩