The Making of Xin Ke (新客)

This 1927 silent Chinese movie is the first feature film to be made in Singapore and Malaya. Jocelyn Lau traces its genesis with researcher Toh Hun Ping and translation editor Lucien Low.

In the mid-1920s, Shen Huaqiang (沈华强), a poor “new immigrant” from China, arrives in Nanyang1 to seek his fortune. He ends up in Johor, staying with his wealthy Peranakan (Straits Chinese) relatives who help him assimilate to life in Nanyang.

Compared with his impoverished counterparts in mainland China, Huaqiang has far better opportunities in his adopted country. Shortly after, Huaqiang’s uncle, Zhang Tianxi (张天锡), finds him a job in Singapore, where over time Huaqiang rises up the ranks through sheer hard work and perseverance.

Meanwhile, Zhang’s elder child, a teenage daughter named Huizhen (慧贞), becomes increasingly aware of her own identity and interests through attending school in Singapore, and grows more confident of herself, and of what she wants in life. Thus, when her father’s English-speaking Peranakan clerk Gan Fusheng (甘福胜) begins to show an interest in her, she senses trouble and rejects him. Huizhen realises that Fusheng is not to be trusted as he indulges in drinking, gambling and womanising. She falls for the hardworking and honest Huaqiang instead.

Unfortunately for Huizhen, her parents think that Fusheng is a pleasant and well-educated person as he speaks and dresses well. Unbeknownst to Huizhen, her parents promise her hand to him in marriage.

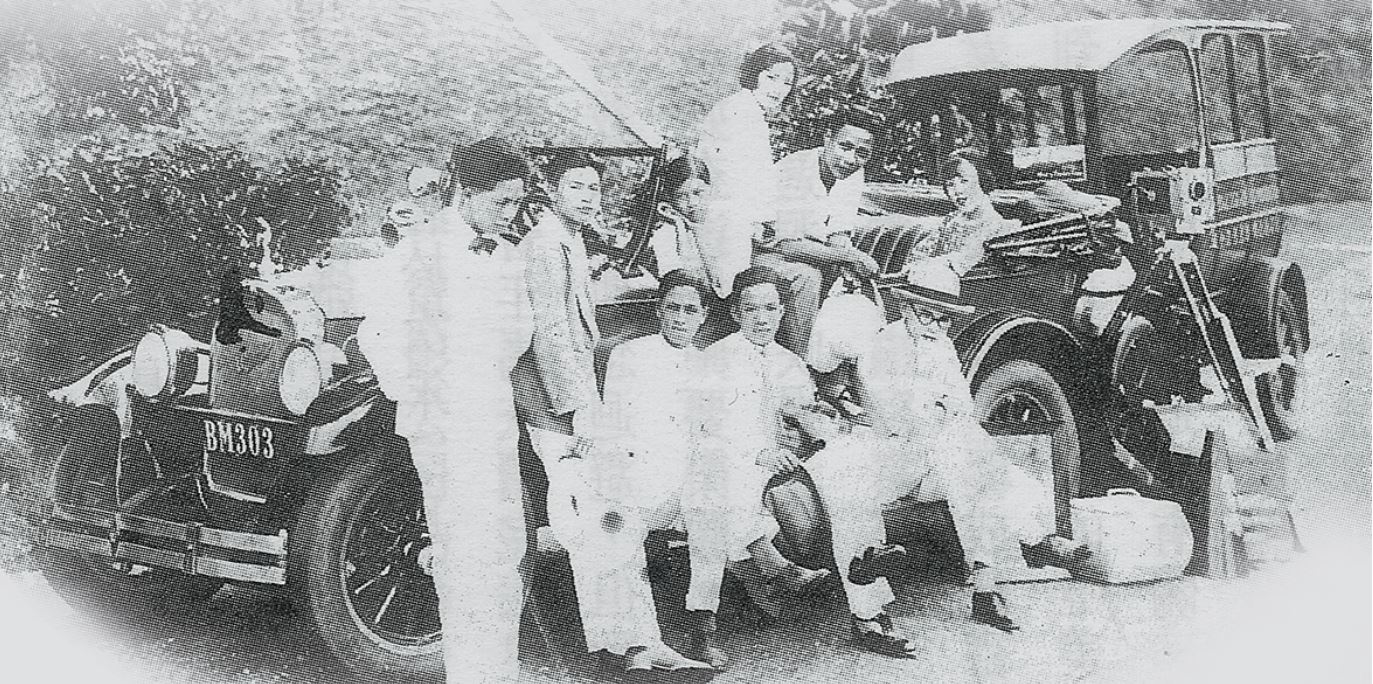

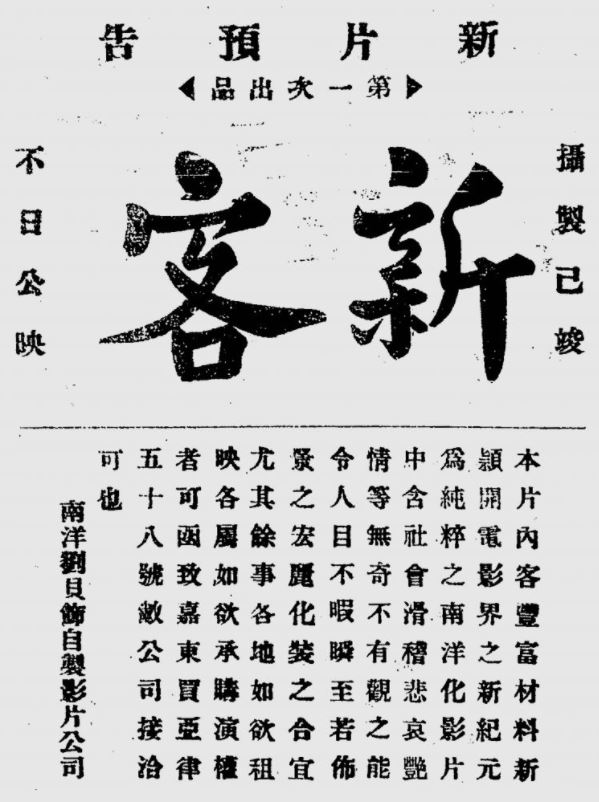

The 1927 silent Chinese film Xin Ke (新客; The Immigrant) is believed to be the very first full-length feature film to have been made in Singapore and Malaya. Xin Ke, like most of the silent films produced globally between 1891 and the late 1920s, has likely not survived the passage of time due to the highly ephemeral nature of the material used back then.2 The items that are still extant today are the film’s Chinese intertitles (see text box below), two synopses, a film still – all published in the local newspaper Sin Kuo Min Press (新国民日报)3 in 1926 – and photos of the film crew and cast.

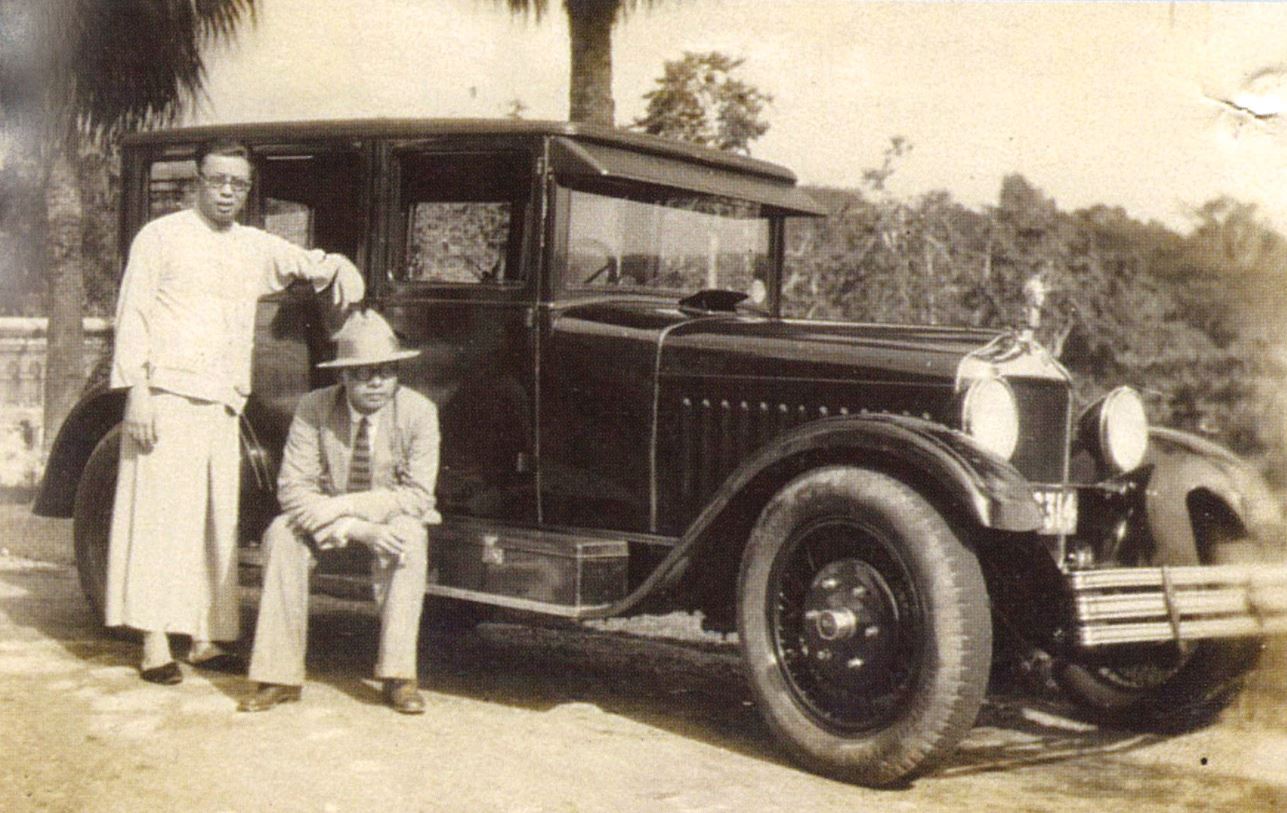

Xin Ke was produced by Liu Beijin (刘贝锦; 1902–59; also known as Low Poey Kim), a prominent Singapore-born entrepreneur. His father, Liu Zhuhou (刘筑侯), was an immigrant from Huyang, Yongchun, in Fujian province, who became one of the wealthiest rubber plantation owners in Muar, Malaya. Liu Beijin was also related to Liu Kang (刘抗; 1911–2004), the pioneer Singaporean artist (Liu Beijin’s and Liu Kang’s fathers were cousins).

A Film Pioneer

Liu Beijin led a very comfortable lifestyle while growing up. He was born in Singapore, and when he was about four months old, his family moved to Muar. When he was six, his father took him back to China, where he lived until he was 16 before returning to Nanyang.4 Back in Muar, Liu took over his father’s rubber plantation business when the latter died at the relatively young age of 56.

Liu was an amiable, well-educated and socially conscious person. He was also a polyglot – fluent in six languages, including English, Mandarin and Malay – and enjoyed dabbling in both business and the arts, particularly motion pictures.

INTERTITLES FROM XIN KE

In order to reach wider audiences, many silent Chinese movies exported from Shanghai in the 1920s and early 1930s for screening in the international market contained both Chinese and English intertitles.5

Likewise, Xin Ke had both Chinese and English intertitles, although only the Chinese texts are still extant. The list of employees who worked on Xin Ke included one person who wrote the Chinese intertitles and another who did the English translation.

The English intertitles numbered 6 to 52, which are reproduced below, have been translated from the extant Chinese intertitles rendered in traditional Chinese characters.

Revised from a script originally written by Chen Xuepu (陈学溥), these title cards were published together with the film’s synopsis in the local newspaper, Sin Kuo Min Press (新国民日报), on 26 November 1926. When the screenplay underwent a second revision and was published in 1927, the new intertitles were – as far as present research has revealed – not included alongside the synopsis.

Zhang Tianxi, an entrepreneur who runs a rubber plantation business.

经营树胶种植之实业家,张天锡。

Zhang’s daughter, Huizhen, is lively and intelligent; it’s a pity she has been influenced by local habits.

张女慧贞,性活泼而聪颖,惜染土人习气。

Huizhen: Daddy, what are you looking at?

慧贞:爸爸!你看什么?

Tianxi: A letter from your cousin: he will be arriving in a few days.

天锡:你表兄寄来的信,他说这几日就要到了。

Huizhen: Which cousin?

慧贞:哪个表兄?

Tianxi: The one from China.

天锡:在中国的。

Huizhen: Oh! That new immigrant.

慧贞:哦!那个新客。

The causeway connecting Singapore and Johore.

新加坡接连柔佛之大铁桥。

Tianxi’s rubber shop.

天锡树胶店。

Tianxi’s English-speaking clerk, Gan Fusheng. Gan is a rogue who indulges in alcohol and women. He looks conscientious and dresses well.

天锡之英文书记甘福胜,性无赖,嗜酒色,貌似纯谨,颇善修饰。

Fusheng: Apa? (Malay: “What?”)

福胜:阿把?(马来语「什么?」)

Fusheng: Tak tahu. (Malay: “Don’t know.”)

福胜:特兜。(马来语「不知」)

Tianxi’s Chinese-speaking clerk, Kang Ziming.

天锡之中文书记,康子明。

Tianxi guides Huaqiang on a tour of the rubber plantation.

天锡导华强参观橡胶园。

Rubber trees, planted months earlier.

种后数月的橡树。

Rubber-tapping.

割胶。

Gathering latex.

收集胶液。

Adding vinegar to the latex.6

胶液,先注以醋。

Smoking the rubber.

继薰以烟。

Machine-rolling rubber into sheets. They are now ready to be sold.

轧以机,成胶片,即可贩卖。

Rubber is Nanyang’s largest produce.

树胶,为南洋出产大宗。

Tianxi’s son, Xinmin.

天锡之子,新民。

Huizhen: Little Brother, a new immigrant has arrived at our house.

慧贞:弟弟,我们家里,来了一个新客。

Xinmin: What’s so special about the new immigrant?

新民:新客有什么稀罕?

Huizhen: Others have said that they are slow-witted! Stupid! They don’t know anything!

慧贞:人家说,新客是呆!笨!什么都不知道!

Xinmin: Really? Let me go take a look at him!

新民:当真吗?让我看看!

Tianxi’s wife, Yu.

天锡之妻余氏。

The next day.

翌日。

Nanyang’s famous fruit, durian, has an odour. People who like it find it tasty. Those who dislike it are repulsed by the smell.

榴梿,南洋著名之果品,有异味,嗜者甘如饴,恶者畏其臭。

Tianxi: New immigrants don’t know how to appreciate it. You have tried it. How does it taste to you?

天锡:新客,是不会吃的,你尝了,味道如何?

Xinmin: Aiyoh!

新民:啊哟!

Fusheng likes Huizhen, and arrives at the Zhang’s residence.

福胜属意慧贞,时至张宅探望。

Fusheng: Sister Hui, I got permission from the Sultan of Johore yesterday to visit the palace today. Do you want to come with me?

福胜:慧妹,我昨日得马来王之许可,今天到皇宫游览,你愿意同去吗?

Huaqiang: What? They allow visits to the palace?

华强:什么!王宫也可以去得的?

Tianxi: Yes, do you want to come along?

天锡:可以的,你要去吗?

Yu: Huizhen, why don’t you go with your cousin?

余氏:慧贞,你和表兄一起去罢。

The Sultan of Johore’s palace.7

柔佛马来王之宫殿。

Returning in high spirits, and passing by Fusheng’s house on the way.

乘兴而归,道经福胜之家。

Fusheng’s mother, Zhao.

福胜之母赵氏。

Zhao: It’s late. Come have lunch with us.

赵氏:时已不早,请吃

午饭去。

Huizhen: Thank you, maybe next time.

慧贞:谢谢!下次再来。

Zhao: Miss Huizhen, lunch is already prepared. Why don’t you oblige us?

赵氏:慧姑,饭已经预备好了,还不赏面吗?

The Babas8 enter the house.

进屋时之哇哇!

Babas like sour and spicy food. Curry is a delicacy.

哇哇味嗜酸辣,加厘尤为上品。

The Babas are eating.

吃饭时之哇哇!

The Babas laugh at Huaqiang when he eats.

华强食饭,哇哇笑之。

Tianxi: Don’t laugh at him. They don’t eat with bare hands in China. If you go to China, they will laugh at you instead.

天锡:你莫笑他,在国内没有用手拿饭的,倘然你到国内去,人家多要笑你哩。

THE ART OF INTERTITLING

In silent films, short lines of text are written or printed on cards, which are then filmed and inserted into the motion picture. During the silent-film era, these texts were called “subtitles”. Known as “intertitles” or “title cards” today, the intermediary lines are used to convey dialogue (dialogue intertitles) or provide narration (expository intertitles) for the different scenes.

Writing intertitles was an art: they had to be concise yet eloquent. A well-worded or witty intertitle enhanced the viewing experience, as did a well-designed title card.

Despite the name, “silent” films were almost always accompanied by live background music – often by a pianist, organist or even an entire orchestra – to create the appropriate atmosphere and to provide emotional cues. This helped to enhance the viewing experience. The music accompaniment also served the practical purpose of masking the whirring drone of the film projector. Sometimes the intertitles were even read out during the film, with the narrators providing commentaries at appropriate junctures.

Reference

Slide, A. (2013). The new historical dictionary of the American film industry (p. 197). New York: Routledge. (Not available in NLB’s holdings)

Between December 1925 and February 1926, when he was about 24 years old, Liu travelled to China to observe the educational, industrial and film industries of the country. Filmmaking was entering a golden age in Shanghai, with local filmmakers taking inspiration from their Chinese roots and the volatile social and political circumstances of the time.

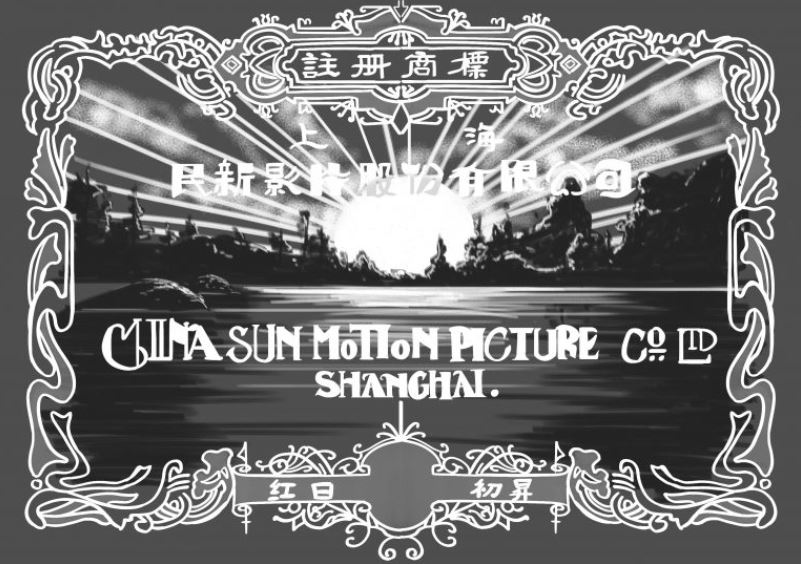

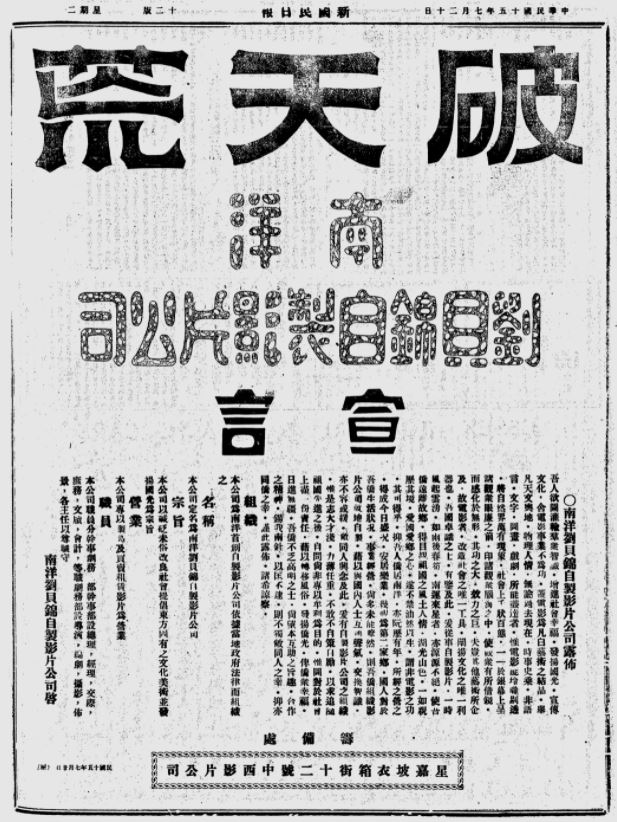

The booming Shanghainese film industry encouraged Liu to establish the Anglo-Chinese Film Company (中西影片公司) in Singapore to distribute Shanghai-made films. Not content with playing a passive role in the film business, Liu co-founded Nanyang Liu Beijin Independent Film Production Company (南洋刘贝锦自制影片公司; also known as Nanyang Low Poey Kim Motion Picture Co.) at 12 Pekin Street. His intention was to produce Chinese films with a “Nanyang” flavour and showcase local talents. Liu’s start-up became the first local film production company in Singapore and Malaya, and one of the earliest in Southeast Asia.9

Liu did not establish the film production company for profit; his intention was to use film – then a relatively new medium – as a means “to instill knowledge among the masses, improve the well being of society [and] promote the prestige of the nation and propagation of culture”.10 To him, the art form, being “the essence of all arts”, had unprecedented potential to “transform” people.

Through his films, Liu wanted to showcase life as it was in Singapore and Malaya to the Chinese in China. Liu also held the view that many among his intended audience in Nanyang – the overseas Chinese – had adopted the unsavoury habits of their countrymen back home, including opium smoking, drinking, gambling and patronising prostitutes, and feudal Chinese customs such as arranged marriages for girls.

A Failed First Screening

Xin Ke was produced between September 1926 and the beginning of 1927. Liu rented a bungalow at 58 Meyer Road, in the affluent beachfront neighbourhood of Tanjong Katong in the east of Singapore, to serve as a studio and film-processing base. The film was shot entirely in Singapore and Malaya, including the bungalow and locations such as the Botanic Gardens, the Causeway and the Istana Besar in Johor.

The first screening of Xin Ke, which was meant to be a preview but was organised more like a premiere,11 was held at the Victoria Theatre on the evening of 4 March 1927. The highly publicised event was free.12 To celebrate the occasion, the organisers published Xin Ke Special Issue, an illustrated souvenir booklet containing information about the Nanyang Liu Beijin Independent Film Production Company and the cast as well as photographs.13

The theatre was reportedly opened to viewers at 7.30 pm and filled to capacity – all “500 seats upstairs and downstairs”14 – by 8 pm, leaving “people without seats”. The film started at 8.30 pm. The audience, comprising mostly women, also included cast members, the film crew and invited guests from the media.15 One of the invited guests, a journalist with the Nanyang Siang Pau newspaper, reported on the event:

“I was able to watch the preview of the first production of Xin Ke by Nanyang Liu Beijin Independent Film Production Company, which opened at Victoria Theatre yesterday at 8 o’clock in the evening. I was honoured to be given a ticket to the film by the company itself. I arrived at the theatre at 7 pm. The workers were still working in the theatre, but there was already a steady stream of people and vehicles at the door. More than 100 viewers had already gathered, and it was crowded. They were only allowed to enter the theatre at 7.30 pm, and by 8 pm, all the seats were already occupied. There were 500 seats upstairs and downstairs, but there were still people without seats. The Singapore General Chamber of Commerce and the various newspaper offices all sent representatives to the event.”16

However, even before the screening began, an announcement was made, causing much confusion among the audience and throwing the evening’s proceedings into disarray. Apparently, the film authorities had censored the last three reels of Xin Ke, leaving only the first six to be shown. An attendee recounted the incident:17

“… someone from the company came announcing in Mandarin: ‘There are only six reels. The government didn’t pass seven, eight and nine.’ The loud and hurried tone caused quite a stir among the guests, but the announcer simply stopped at that and left. Not long after that, another representative came out and explained, in Cantonese, that for some special reasons, the three reels were banned by the censorship board and thus could not be screened together with the rest. It was then that the audience understood the reason for the delay.”18

| THE CAST OF CHARACTERS | |

| CAST | CHARACTERS |

| Zheng Chaoren (郑超人) | Shen Huaqiang (沈华强) |

| Chen Ziying (陈子缨) | Zhang Tianxi (张天锡) |

| Wo Ying (我影) | Yu (Zhang Tianxi’s wife) (余氏; 张天锡之妻) |

| Lu Xiaoyu (陆肖予) | Zhang Huizhen (Zhang Tianxi’s daughter) (张慧贞; 张天锡之女) |

| Chen Bingxun (陈炳勳) | Zhang Xinmin (Zhang Tianxi’s son) (张新民; 张天锡之子) |

| Zhang Danxiang (张淡香) | Liu Boqi (刘伯憩) |

| Yun Ruinan (云瑞南) | Yan (Liu Boqi’s wife) (颜氏; 刘伯憩之妻) |

| Wan Cheng (晚成) | Liu Jieyu (Liu Boqi’s daughter) (刘洁玉; 刘伯憩之女) |

| Huang Mengmei (黄梦梅) | Gan Fusheng (甘福胜) |

| Tan Minxing (谭民兴) | Zhao (Gan Fusheng’s mother) (赵氏; 甘福胜之母) |

| Yi Chi (一痴) | Kang Ziming (康子明) |

| Kang Xiaobo (康笑伯) | Yujuan (玉娟) |

| Xiao Qian (笑倩) | Zhao Bing (赵丙) |

| Fang Zhitan (方之谈) | Old farmer (老农) |

| Zheng Chongrong (郑崇荣) | Female student (女学生) |

| Chen Mengru (陈梦如) | Guest (贺客) |

| Zhou Zhiping (周志平) | Guest (贺客) |

| Zhang Qinghua (张清华) | Guest (贺客) |

For silent films produced in the 1920s, one standard reel of 1,000 ft (305 m) of 35 mm film ran at approximately 16 frames per second, which meant that each reel was around 15 minutes long. The exclusion of three entire reels caused about 45 minutes of the film to be excised. Not surprisingly, the removal of the film’s conclusion affected the storyline and cast a pall on the viewing experience.

The reasons for the censorship were not released, but it is believed that the Official Censor objected to the graphic scenes of violence and fighting in the last three reels. Unfortunately, all nine reels of film no longer exist. Liu had planned to shoot a revised conclusion but it is unclear whether this eventually materialised.

Subsequent Screenings

Shortly after that failed first screening, it is likely that Xin Ke continued to be shown in cinemas in Singapore, but so far there has been no documentary evidence to support this. More certain is the fact that screenings took place in Kuala Lumpur, Melaka and Hong Kong.

In Kuala Lumpur, the film was screened on 27 May 1927 at the Empire Theatre (also known as Yi Jing Garden Cinema), but attendance was dismal. The film similarly met with little enthusiasm in Melaka. Over in Hong Kong, the film was shown at Kau Yue Fong Theatre under a different title, Tangshan Lai Ke (唐山来客), from 29 April to 2 May 1927. It is not clear if the film was also censored or whether it garnered more favourable reviews.

In May 1927, Liu was forced by personal circumstances to close his film production company for good. He had planned to produce a second feature, A Difficult Time (行不得也哥哥), but shooting was never completed. Liu tried to revive his film production business in 1929, but he would not make another motion picture again.

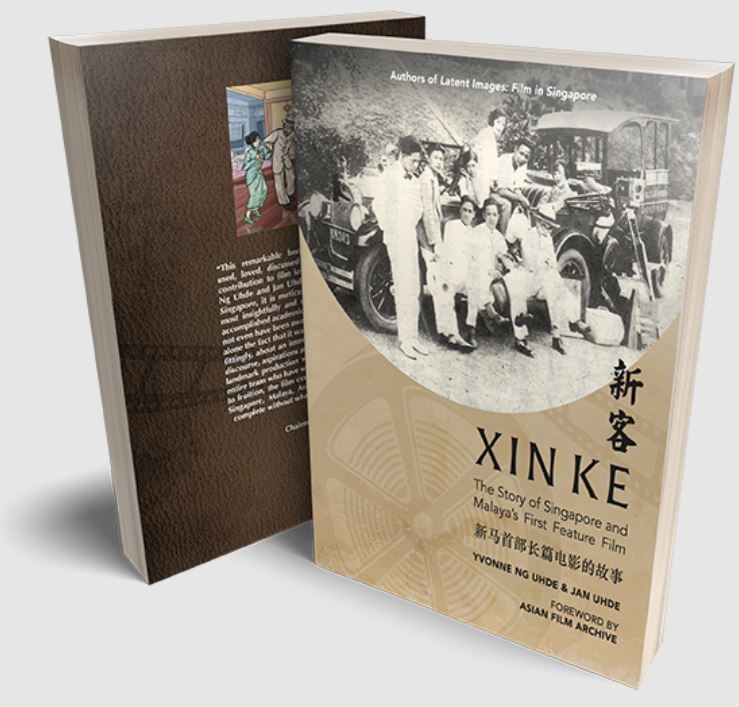

This essay is abridged from the recently published book, Xin Ke: The Story of Singapore and Malaya’s First Feature Film (新客: 新马首部长篇电影的故事) (2019), written by Yvonne Ng Uhde and Jan Uhde, edited by Toh Hun Ping, Lucien Low and Jocelyn Lau, and published by Kucinta Books. It retails for $28 at major bookshops and is also available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 791.43095957 UHD and SING 791.43095957 UHD).

Jocelyn Lau is a an editor and a writer with postgraduate qualifications in publishing. She is the co-publisher of Kucinta Books.

Jocelyn Lau is a an editor and a writer with postgraduate qualifications in publishing. She is the co-publisher of Kucinta Books.

NOTES

-

Nanyang (南洋; literally “Southern Ocean”) refers to Southeast Asia. ↩

-

Films that were produced in the early 20th century were very unstable as they were made from a chemical base using cellulose nitrate. The material deteriorated steadily over time and also had the tendency to self-ignite. ↩

-

《新国民杂志银幕特号》(1926, November 26). Sin Kuo Min Press, p. 14; 《银幕世界新客特号》. (1927, February 5). Sin Kuo Min Press, p. 15. (Microfilm no.: NL33031). ↩

-

Liu, B.J. (1926). 《刘贝锦归国记》 [Liu Beijin’s homecoming journal] (p. 28). Shanghai: Sanmin gongsi [三民公司]. There is conflicting information about Liu having graduated from Chung Hwa School (中华学校), a primary school in Muar, in 1916, when he was 14. From Li, Y.X. (李云溪) (Ed.). (1972). A history of the school (1). In 60th Anniversary Souvenir, Chung Hwa High School, Muar, Malaysia (1912–1972). Muar: Chung Hwa High School (n.p.). (Call no.: Chinese RSEA 373.09595 CHU). ↩

-

In the 1930s, the Chinese Nationalist government prohibited the addition of English intertitles to Chinese films that were intended for domestic screening. This was to promote the national language and to stop what it perceived as the excessive use of foreign languages in China. As a result, bilingual intertitles in Chinese films disappeared, and Chinese films were translated only if they were screened overseas. See Jin, H.N. (2018). Introduction: The translation and dissemination of Chinese cinemas. Journal of Chinese Cinemas, 12 (3), 197–202. (Not available in NLB holdings). ↩

-

Vinegar is a diluted form of acetic acid that was added to latex so that it would coagulate. ↩

-

The Istana Besar, also known as the Grand Palace, was the 19th- and early 20th-century residence of the Sultan of Johor. Built in 1866 by Sultan Abu Bakar (1833–95), the palace overlooks the straits of Johor and Singapore. ↩

-

Peranakan men are known as baba, while the women are referred to as nonya. In this context, the reference is to Peranakans in general. ↩

-

Tan, B.L. (Interviewer). (1982, December 30). Oral history interview with Liu Kang 刘抗 [Transcript of recording no. 000171/74/32, pp. 293–297]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Liu, B.J. (1926, July 20). 《破天荒:南洋刘贝锦自制影片公司宣言》 [Manifesto: A public notice by Nanyang Liu Beijin Independent Film Production Company]. Sin Kuo Min Press, p. 12. (Microfilm no.: NL33031) ↩

-

《南洋刘贝锦自制影片公司启事》 [Notice from Nanyang Liu Beijin Independent Film Production Company]. (1927, March 1). Sin Kuo Min Press, p. 6. (Microfilm no.: NL33031) Preview or test screenings were usually held prior to the general release of a film to gauge audience response and might lead to changes in the film, such as the title, music and scenes. However, the “preview” screening of Xin Ke functioned more like a premiere as it was held in a grand venue with the cast, crew and press in attendance. ↩

-

Sin Kuo Min Press, 1 Mar 1927, p. 6; Extract from 《显微镜》 [Microscope]. (1927, March 12). The Joke of Xin Ke. Marlborough Weekly, 23, p. 2 (Part 1); 《显微镜》 [Microscope]. (1927, March 19). Marlborough Weekly, 24, p. 2 (Part 2). (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Xin Ke Special Issue appears to be no longer extant. ↩

-

Victoria Theatre. (1909, February 1). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

《贺嘉》 [He, J.]. (1927, March 7). 《银幕消息:观「新客」试映记》 [Watching a preview of Xin Ke]. Nanyang Siang Pau, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

This is an English translation. See Nanyang Siang Pau, 7 Mar 1927, p. 4. ↩

-

《显微镜》 [Microscope], 12 Mar 1927, p. 2. ↩

-

This is an English translation. See 《显微镜》 [Microscope], 12 Mar 1927, p. 2. ↩