From Gambier to Pepper: Plantation Agriculture in Singapore

Timothy Pwee takes us on a tour through pepper, gambier, nutmeg, pineapple and rubber plantations that were once common in 19th-century Singapore.

A gambier and pepper plantation in Singapore, c. 1900. Pepper and gambier are often grown together. The boiled gambier leaves provide the much-needed fertiliser for pepper plants. Pepper vines also entwine around the gambier plants for support as they grow. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

A gambier and pepper plantation in Singapore, c. 1900. Pepper and gambier are often grown together. The boiled gambier leaves provide the much-needed fertiliser for pepper plants. Pepper vines also entwine around the gambier plants for support as they grow. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Being a free port astride a major trading route between the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea enabled Singapore to flourish in the 19th century. While Singapore’s wealth was clearly built on trade, this tends to overshadow the fact that for much of the 19th and well into the 20th century, commercial agriculture was a significant economic activity on the island as well.

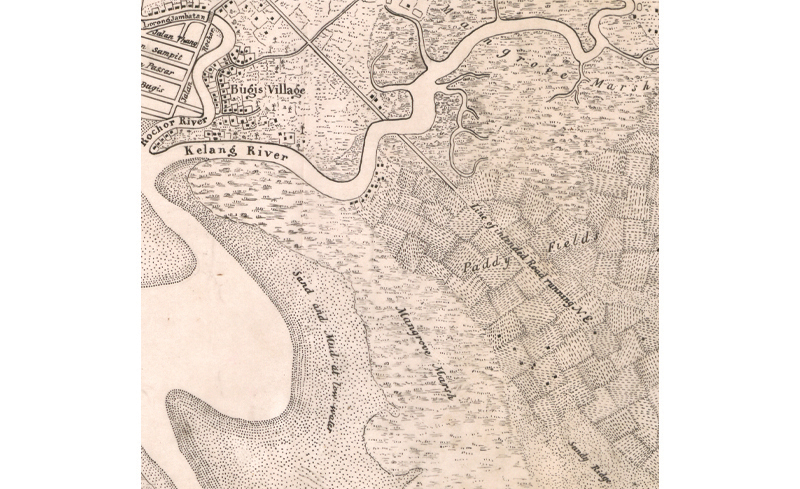

The first topographical survey of Singapore Town – conducted by colonial architect George D. Coleman in 1829 and which yielded the Map of the Town and Environs of Singapore in 1836 – showed large plots of land dedicated to agriculture on the outskirts of settled areas. There were paddy fields on the eastern banks of the Kallang River, while to the east of these fields, land had been cleared for the growing of sugar and cotton. In addition, the area south of the paddy fields was used for the cultivation of the betel vine. Around what is now the Orchard Road area were gambier plantations.1 About a decade later, coconuts had taken over the paddy fields, according to Government Surveyor John Turnbull Thomson’s 1844 map of Singapore town and the adjoining districts. Meanwhile, pineapples were being grown on Pulau Blakang Mati (present-day Sentosa) and there were nutmeg orchards in the Claymore district (today’s Orchard Road).2

Detail from the 1836 Map of the Town and Environs of Singapore showing the land east of the Kelang (Kallang) River planted with rice. However, the land was soon dominated by coconut plantations. The map was drawn by Jean-Baptiste Athanase Tassin, a renowned French lithographer and cartographer, and printed in Calcutta. It was based on George D. Coleman’s 1829 survey of Singapore, which is the earliest known topographical survey of Singapore town. This map is useful in showing the various crops produced on the outskirts of the town in the 1830s. Survey Department Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Detail from the 1836 Map of the Town and Environs of Singapore showing the land east of the Kelang (Kallang) River planted with rice. However, the land was soon dominated by coconut plantations. The map was drawn by Jean-Baptiste Athanase Tassin, a renowned French lithographer and cartographer, and printed in Calcutta. It was based on George D. Coleman’s 1829 survey of Singapore, which is the earliest known topographical survey of Singapore town. This map is useful in showing the various crops produced on the outskirts of the town in the 1830s. Survey Department Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Since the arrival of the British in 1819, large swathes of land in Singapore had been used for the cultivation of commercial crops – the most important of which were pepper, gambier, nutmeg, coconut, pineapple and rubber. While plantation agriculture is no longer practised in Singapore, these long-gone plantations have had a significant impact on Singapore’s economy, environment and biodiversity.

Gambier and Pepper – a Close Connection

The earliest recorded plantations in Singapore were devoted to growing gambier. When Stamford Raffles landed here in 1819, he found that he had been preceded by the Chinese, mostly Teochew, who were growing the crop.3

At the time, gambier was being planted in the region, including on the Riau Islands and in Penang, so it would not have been surprising to encounter gambier planters in Singapore. In 1822, the first Resident, William Farquhar, writes of a Chinese gambier plantation west of Government Hill (today’s Fort Canning). That same year, James Pearl, the captain of the ship Indiana that brought Raffles to Singapore, purchased land on the western side of the hill from the gambier planter Tan Ngun Ha. Pearl began to acquire more plots on the hill from Chinese gambier planters until he owned the entire hill. Today, this hill in Chinatown is known as Pearl’s Hill.4

Gambier is a fast-growing shrub whose foliage can be harvested in about 14 months. The leaves and twigs are first boiled and the resulting paste is then dried. The final product, popularly called catechu, contains both tannins and catechin.

In the early 19th century, catechu was mainly used as an additive in the betel quid. The catechu and lime were smeared on the betel leaf (known locally as sireh), which was then wrapped around small slices of areca nut. Betel chewing was a habit that was popular in the region at the time.5

The gambier shrub looks quite nondescript, with the most notable feature being its bright yellow inflorescence. Jessica Teo, NParks Flora&FaunaWeb.

The gambier shrub looks quite nondescript, with the most notable feature being its bright yellow inflorescence. Jessica Teo, NParks Flora&FaunaWeb.

Much of the produce went to Batavia (now Jakarta) in the Dutch East Indies and distributed throughout the region. However, this came to a sudden halt in 1827 with the imposition of restrictive duties by the Dutch. This caused a crash and many gambier plantations, including those in Singapore, went out of business.6

The industry revived in the 1830s though as gambier was discovered to be a good source of tannic acid, used for tanning leather and dyeing textiles. Demand from England, and later the Americas, caused a boom regionally. Among the beneficiaries was businessman Seah Eu Chin. In 1835, he purchased an 8-mile (almost 13 km) stretch of land between River Valley Road and Bukit Timah Road for his gambier plantations. This made him the largest gambier planter in Singapore, earning him the moniker “Gambier King”.7

Commonly grown alongside gambier is pepper. Although pepper was a much more profitable crop, the plant takes three years before it can be harvested. Additionally, the pepper plant is a vine that requires frames for support to grow upwards and also needs to be fertilised regularly. The boiled gambier leaves provide much-needed fertiliser for pepper plants which is why the two crops are often grown together; gambier would be planted while waiting for the pepper vines to start bearing fruits.

Unfortunately, growing gambier and pepper takes a significant toll on the land as the crops exhaust the soil drastically and render it infertile after about 15 years. In addition, the purification of gambier catechu required so much firewood that the forests surrounding gambier plantations would be stripped of wood for fuel. This meant moving elsewhere to start the cycle all over again.

The result was a pattern of shifting cultivation that started from the Singapore River area and eventually spreading across the island until practically the entire island had been exploited. By the 1860s, Singapore’s gambier output had begun to decline as planters moved to Johor. However, it was only at the close of the 19th century that gambier planting finally faded into oblivion.8

The Blighted Nutmegs

Another cash crop that was cultivated in 19th-century Singapore was nutmeg, which was one of the major spices that drove the colonial enterprise in Southeast Asia. Two spices are actually produced from the plant: nutmeg and mace. The nutmeg spice comes from the seed, while mace comes from the aril, the red lacy layer surrounding the seed. Both nutmeg and mace are similar in taste, with mace described as being more delicate. Given its desirability and profitability, nutmeg was an obvious crop for the pioneer merchants in Singapore to cash in on.

The black seed of the nutmeg fruit is ground to make the nutmeg spice, while the red aril around the seed is used to make another spice known as mace. Locally, the flesh is eaten pickled as buah pala. Courtesy of Boo Chih Min, NParks Flora&Fauna Web.

The black seed of the nutmeg fruit is ground to make the nutmeg spice, while the red aril around the seed is used to make another spice known as mace. Locally, the flesh is eaten pickled as buah pala. Courtesy of Boo Chih Min, NParks Flora&Fauna Web.

After Raffles established a trading post on Singapore, he sent over nutmeg seeds and saplings from Bencoolen (now Bengkulu), on the island of Sumatra, where he was Lieutenant-Governor. Nutmeg plantations were then established along what is today’s Orchard Road and in Tanglin. Although the nutmeg trees had thrived initially, there were later problems with blight.

When William Montgomerie, Assistant Surgeon with the Bengal Native Infantry, returned to Singapore in 1835, he found that the nutmeg trees planted on Raffles’ instructions a decade and a half earlier had been neglected and were diseased.9 He estimated that there were about 25,000 nutmeg trees in Singapore with only a few hundred being over 10 years old.10

One reason for the large number of new trees from the 1830s onwards is that the lease periods for land were initially shorter. It was only in 1828 that the government started giving out longer land leases of 20 years, with the option to renew for another 30 years.11 George Windsor Earl, writing in The Eastern Seas in 1837, observed that “there are no European planters in the island of Singapore; nor is it probable that any British-born subject will venture to engage in agricultural speculations, since the system of land tenure would destroy all confidence, and all hope of profit in the planter”.12

However, the longer land leases from 1828 onwards appeared to have given some Europeans the assurance that they could plant nutmeg saplings and reap some profit when the trees matured and bore fruit. In 1834 for instance, a plot of land in the Duxton area of Tanjong Pagar that had been planted with nutmeg trees was offered at an auction with a 15-year lease that began in 1827.13 Montgomerie bought the land and planted more nutmeg trees. In 1843, the government started issuing what is now called freehold land, and by the time of Montgomerie’s passing in 1856, his plot in Duxton had become freehold land. He must have purchased the freehold title to it, most likely in 1842 when the original lease expired.14

Although Singapore was now a nutmeg producer, its output trailed behind Penang which was already producing enough nutmeg to meet the demand from Britain by 1842. This caused the price of nutmegs in Penang to plummet from $10–$12 per thousand to $4–$5 per thousand.15 This did not deter planters, and the mania for planting nutmeg trees in Singapore continued unabated. John Cameron’s 1865 Our Tropical Possessions in Malayan India noted: “What had been flower gardens and ornamental grounds of private residences were turned over, and nutmegs planted to within a stone’s throw of the house walls. Besides this, large tracts of jungle, at a distance of four or five miles from town, were bought up from Government, cleared at great expense, and turned into plantations. Some of these newly reclaimed properties… changed hands at exorbitant prices.”16

However, from the 1850s, the nutmeg trees were again plagued by the mysterious blight that blackened branches and killed the fruits. During that decade, nutmeg plantations were decimated just as the original nutmeg trees planted in the 1820s had been. In 1897, Director of the Botanic Gardens Henry Nicholas Ridley diagnosed these symptoms as being caused by the nutmeg beetle (Phloeosinus ribatus).17

Coconuts on Sandy Beaches

Another important plantation crop grown in Singapore in the 19th century was coconut. An 1841 Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser report noted that “[no] trees of this kind can well be more flourishing than those in the plantations which stretch along the seashore to the N.E. of the Town – and which growing on the Island called Blakang Mati”, and estimates that “[t]here are perhaps about 50,000 trees now planted out and occupying about 660 acres of land”.18

In 1849, it was estimated that coconut plantations occupied 2,658 acres in Singapore, even larger than the area used for nutmeg plantations which took up 1,190 acres.19 Coconut was the second largest crop by acreage behind gambier and pepper (by far the largest at 27,000 acres).

A history of Joo Chiat identifies Francis Bernard as the pioneer coconut estate planter on the eastern coast of Singapore.20 The son-in-law of first Resident William Farquhar, Bernard started planting coconuts in 1823 and was followed in the subsequent decades by other Europeans such as Thomas Dunman (the first Commissioner of Police in Singapore from 1856 to 1871) and Chinese businessmen like Hoo Ah Kay21 (better known as Whampoa). Dunman’s estate was one of the biggest, stretching from today’s Fort Road to Tanjong Katong Road and reaching inland to Dunman Road, which was named after him.

As Singapore’s long and sandy south eastern coast was conducive for growing coconuts, these plantations became characteristic of the area. Unfortunately, these plantations also eventually wiped out the coastal forests.22

Smaller coconut plantations were found elsewhere on the island, like a 30-acre nutmeg and coconut estate on Bukit Timah Road, which was put on auction in 1845.23 Planting different types of crops in one plantation was not uncommon. In the early decades especially, planters would experiment with different crops. Jose d’Almeida, a Portuguese naval surgeon who arrived in Singapore in 1825 and set up a dispensary in Commercial Square (now Raffles Place), was one such example. He later became a landowner and one of Singapore’s leading merchants. On his Confederate Estate in Tanjong Katong, he tried but failed with cotton before turning to coconut.24

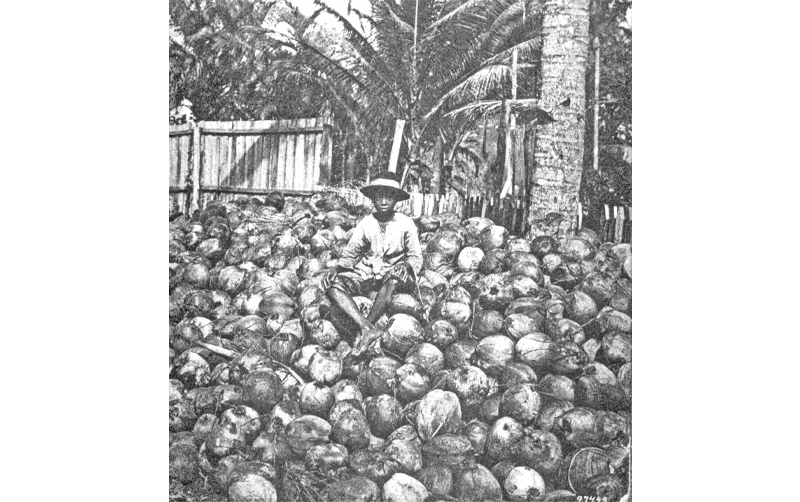

A young worker sitting atop harvested coconuts in a coconut estate in Singapore, 1922. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A young worker sitting atop harvested coconuts in a coconut estate in Singapore, 1922. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Pineapples and the Canning Industry

The pineapple, indigenous to South America, was one of the native food plants from the Americas, like chilies, potatoes and tomatoes, that was spread by Europeans to the rest of the world in the 17th century. Surprisingly, it was Singapore’s third largest crop by acreage in 1849.25

Pineapple seems to have been a popular fruit and was originally cultivated by the Bugis on the southern islands and in Telok Blangah as can be seen from mid-19th century maps of the area. The earliest mention of pineapple cultivation appears to be a Singapore Chronicle article by second Resident John Crawfurd, published around 1824.26 John Cameron states in Our Tropical Possessions in Malayan India that the pineries in Telok Blangah belonged to the Temenggong and these were mainly for sale in Singapore.27

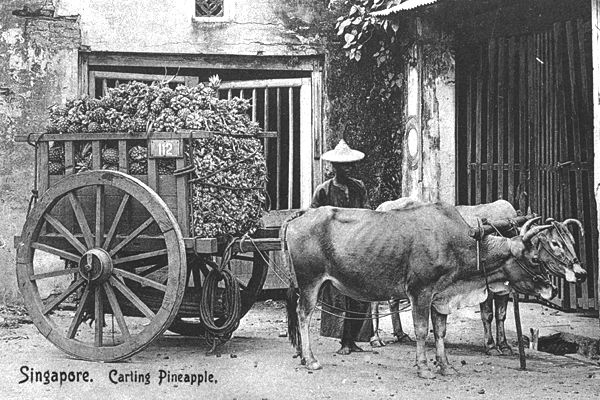

Freshly harvested pineapples in Singapore being transported by a bullock cart to be sold, 1900s. Pineapples grown in Singapore and the Malay Peninsula became a major canned export from the 1900s onwards. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Freshly harvested pineapples in Singapore being transported by a bullock cart to be sold, 1900s. Pineapples grown in Singapore and the Malay Peninsula became a major canned export from the 1900s onwards. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Ownership of the offshore-island estates is less clear although accounts in the mid-1800s agree that they were cultivated by the Bugis.28 English navigator George Windsor Earl’s 1837 account suggests that there might be Javanese cultivators as well: “On the coast of the island to the eastwards of the town, and also on the little islets off the harbour, are small agricultural settlements of Bugis and Javanese.”29

Writing in 1841, Joseph Balestier, the first American Consul to Singapore, and William Montgomerie, then Head of the Medical Department in Singapore, noted that although the pineapples growing on the island “are of a superior quality… are large [and] sweet and well flavoured” and “eagerly consumed by the lower classes”, they also cautioned that the pineapple is “not a wholesome fruit and… assisted the cholera in the ravages it made here last spring; when it is believed from six to seven hundred natives died of that dire disease”.30

At the time, there was no hint of the fruit being exported but there was apparently a small export market to China for the pineapple leaf fibre.31 Called piña in the Philippines, it was often combined with silk or cotton to weave into textiles. From the 1870s onwards, when the British developed Pulau Blakang Mati into a defence post to protect shipping passages due to its strategic location, the Bugis-owned pineapple gardens on the island appeared to have gone into retreat.

It was only with the advent of canning or tinning technology that the pineapple became exportable in the days before air freight and nitrogen storage. The high acidity of pineapple made it ideal for preventing the growth of Clostridium botulinum, an anaerobic bacterium that produces the deadly botulinum toxin. If not properly sterilised, this bacterium thrives in canned food and its toxin can cause paralysis and even death.

A certain Frenchman, known only as Laurent, began canning pineapples in Singapore around 1875 but this effort was short-lived.32 Another Frenchman, a war veteran and seaman named Joseph Pierre Bastiani, started exporting canned pineapples from Singapore to Europe in the mid- to late 1870s.

Pineapples grown in Singapore and the Malay Peninsula became a major canned export from the 1900s. In 1907 alone, 846,000 cases of preserved pineapples were exported from Singapore as “pineapples grown in the Straits Settlements are favoured in the European markets,” noted The Straits Times.33

The pineapple estates that were established to supply this new canning industry were Chinese-owned and located inland rather than along the rocky coast.34 These pineapple estates helped build the fortunes of several people, notably that of Tan Kah Kee.35 Tan, who later became a philanthropist and prominent leader of the Chinese community in Singapore, started a pineapple cannery called Sin Lee Chuan in Sembawang and established Hock Shan Plantation in 1904. Blessed with an acute business acumen, Tan sensed the opportunity of rubber and quickly interplanted rubber trees in his pineapple plantation. He made a fortune selling it off as a rubber estate (with rights to continue harvesting the pineapples).

It soon became a common practice for rubber plantation owners to plant pineapples while waiting for the rubber trees to mature as this allowed them to earn some revenue in the initial years. Tan became a pineapple canning tycoon, controlling over 70 percent of the output in Singapore,36 before an embargo during World War I (1914–18) disrupted trade. His son-in-law, Lee Kong Chian,37 would also go into the pineapple plantation business but would focus his work on the peninsula where Lee Pineapple still operates today. Like rubber, pineapple’s viability would be ended by Singapore’s expanding population and industrialisation.

The Rise of Rubber

After the blight killed off nugmeg trees in Singapore, coconuts and pineapples became the dominant choices for Singapore’s plantations. In addition, other less common crops like tapioca and Liberian coffee were planted as well. However, the increasing use of electricity and the rise of the automobile sparked a boom in a new commodity that provided both insulation for electric wires and pneumatic tyres – rubber.

Ridley, Director of Singapore’s Botanic Gardens, persuaded local merchants to try growing Pará rubber which eventually became a major cash crop in both Singapore and the peninsula. Ridley’s first convert was Tan Chay Yan, who became the first rubber planter in Malaya.38 In 1898, Tan started Asahan Estate in Melaka after a successful trial run at Bukit Lintang two years earlier. In Singapore, Tan subsequently entered into an agreement with other prominent Chinese merchants to establish Sembawang Rubber Plantations Limited, and Tempines Para and Coconut Plantations Limited in 1910.39

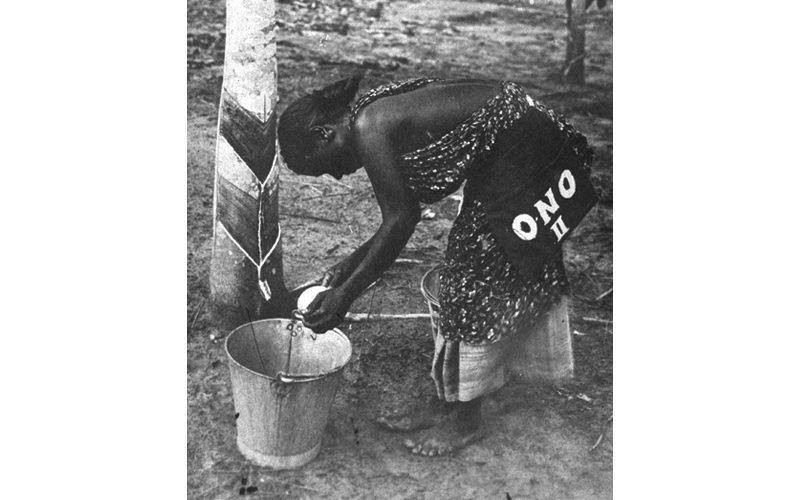

A worker tapping latex in a rubber plantation in Singapore, 1930s. Henry Nicholas Ridley, Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens (1888–1912), invented the “herringbone” technique that allowed rubber trees to be tapped at regular intervals without causing the trees any harm. The herringbone-pattern incisions can be clearly seen on the trunk of the tree. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A worker tapping latex in a rubber plantation in Singapore, 1930s. Henry Nicholas Ridley, Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens (1888–1912), invented the “herringbone” technique that allowed rubber trees to be tapped at regular intervals without causing the trees any harm. The herringbone-pattern incisions can be clearly seen on the trunk of the tree. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Although rubber could yield significant profits for plantation owners, the initial outlay was very high as rubber plantations tied up huge amounts of capital in the land, maintenance, labour and basic processing of the latex into transportable sheets. There were, however, eager British investors willing to put their money into rubber companies that promised regular dividends. London brokers quickly coordinated the floating of companies to buy over Malayan rubber plantations and engage local agents to manage these plantations. This allowed for huge plantations with the accompanying economies of scale to flourish. If the original local owners wanted to continue investing in the plantations, they would accept shares in the London company in lieu of part of the purchase price.

Two London-based companies, Bukit Sembawang Rubber Company Limited and Singapore United Rubber Plantations Limited, were formed to acquire the companies of Tan Chay Yan’s coalition in exchange for shares in these London companies. The holdings of the London companies, plus further acquisitions of neighbouring estates, totalled over 12,000 acres by 1912.40 Combined, this made them one of Singapore’s largest landowners, whose holdings stretched from Jurong to Changi.

But the rubber trade in Singapore soon hit a major speedbump. Japan’s growing military might and Britain’s pivot away from an alliance with the Japanese to the United States made it necessary to construct a naval base in Southeast Asia for the British Imperial Fleet should it need to fight in the Pacific. Construction of the naval base in Sembawang, along with associated defences like airfields, meant the compulsory acquisition of large chunks of land from Bukit Sembawang and Singapore United companies in 1923. More acquisitions happened over the years as the military presence in Singapore grew.

When the Japanese Occupation (1942–45) ended, the rapid growth of Singapore’s population necessitated the clearing of more land for homes and for development.41 But this housing need also presented an opportunity as land became more valuable. In 1954, a new company, Bukit Sembawang Estates Limited, was created to take over blocks of plantation land from the two earlier companies and build low-cost housing for sale.42 Another company was created to provide loans to prospective buyers.

The first project was Bukit Sembawang Hills in 1954, a landed estate just south of the junction of Yio Chu Kang Road and Upper Thomson Road. Bukit Sembawang would eventually acquire the two companies in London and become the property developer, Bukit Sembawang Estates Limited, of today.

Of course, this was not the typical fate of smaller rubber plantation companies and rubber tapping smallholdings in Singapore. These would mostly be sold, acquired or fade into oblivion, thereby closing the chapter on Singapore’s plantation era.

Timothy Pwee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is interested in Singapore’s business and natural histories and is developing the library’s donor collections around these areas.

Timothy Pwee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is interested in Singapore’s business and natural histories and is developing the library’s donor collections around these areas.

NOTES

-

Survey Department, Singapore. (1836). Map of the town and environs of Singapore [Map]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

A second edition was published in 1846. See National Archives of Singapore. (1846). Plan of Singapore town and adjoining districts [Map]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Tan, G.L. (2018). An introduction to the culture and history of the Teochews in Singapore (p. 44). Singapore: World Scientific. (Call no.: RSING 305.895105957 TAN) ↩

-

Bartley, W. (1969, July). Population of Singapore in 1819. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 42 (1), 112–113. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

For more information about betel chewing, see Lim, F., & Pakiam, G. (2020, October–December). A bite of history: Betel chewing in Singapore. BiblioAsia, 16 (3), 4–9. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Low, S.C. (1955). Gambier-and-pepper planting in Singapore, 1819–1860 (p. 36) [University of Malaya, Singapore; thesis]. [n.p.]. (Call no.: RCLOS 630.95957 LOW) ↩

-

Song, O.S. (1923). One hundred years’ history of the Chinese in Singapore (p. 20). London: John Murray. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.57 SON; Accession no.: B02956336A). For more information about Seah Eu Chin, see Yong, C.Y. (2016). Seah Eu Chin. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Montgomerie, W. (1843–44). Cultivation of nutmegs at Singapore. Transactions of the Society, Instituted at London, for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce, 54, 38–50. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Balestier, J., & Montgomerie, W. (1841, November 25). From an unpublished journal of a residence at Singapore: During part of 1840 & 41. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lee, K.L. (1984). Emerald Hill: The story of a street in words and pictures (p. 1). Singapore: National Museum of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 LEE) ↩

-

Earl, G.W. (1837). The eastern seas, or voyages and adventures in the Indian Archipelago, 1832–33–34 (pp. 408–409). London: W.H. Allen & Co. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 915.980422 EAR; Accession no.: B02948006G) ↩

-

Duxton. (1834, January 1). Singapore Chronicle and Commercial Register, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 4 Advertisements Column 2: For sale by auction, the valuable nutmeg plantation, belonging to the estate of the late Dr. Montgomerie. (1856, September 9). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The statistics of nutmeg. (1849). The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, Vol. III. pp. iii–vii, p. iv. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 950.05 JOU; Accession no.: B03013629B) ↩

-

Cameron, J. (1865). Our tropical possessions in Malayan India: Being a descriptive account of Singapore, Penang, Province Wellesley, and Malacca; Their peoples, products, commerce, and government (p. 168). London: Smith, Elder & Co. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 959.5 CAM-[JSB]; Accession no.: B29032445G) ↩

-

Ridley, H.N. (1897, April). Spices. Agricultural Bulletin of the Malay Peninsula, (6), 96–129, p. 106; De Guzman, C.C., & Siemonsma, J.S. (Eds.). (1999). Spices. Bogor, Indonesia: PROSEA Foundation. (Call no.: RCLOS 633.830959 SPI). For more information about Henry Nicholas Ridley, see Cornelius-Takahama, V. (2016). Henry Nicholas Ridley. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Balestier, J., & Montgomerie, W. (1841, November 11). From an unpublished journal of a residence at Singapore: During part of 1840 & 41. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 23. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Brooke, G.E. (1921). Botanic gardens and economic notes (p. 71). In W. Makepeace, G.E. Brooke & R.St.J. Braddell (Eds.), One hundred years of Singapore (Vol. II; pp. 63–78). London: John Murray. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.51 MAK) ↩

-

Kong, L., & Chang, T.C. (2001). Joo Chiat: A living legacy (p. 29). Singapore: Joo Chiat Citizens’ Consultative Committee & National Archives of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING q959.57 KON) ↩

-

For more information about Hoo Ah Kay, see Tan, B. (2019, August). Hoo Ah Kay. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Corlett, R.T. (1992, July). The ecological transformation of Singapore. Journal of Biogeography, 19 (4), 411–420. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Page 1 Advertisements Column 3: Notice. (1845, June 12). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Buckley, C.B. (1902). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore (Vol. I; p. 185). Singapore: Fraser and Neave. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 959.57 BUC; Accession no.: B02966440I). For more information about Jose d’Almeida, see Ong, E.C. (2019, May). Jose d’Almeida. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1849). Agriculture of Singapore. The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, Vol. III, 508–511, p. 509. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 950.05 JOU; Accession no.: B03013629B) ↩

-

Little, R. (1848). An essay on coral reefs as the cause of Blakan Mati fever, and of the fevers in various parts of the East. The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, Vol. II, 571–602, pp. 573–583. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 950.05 JOU; Accession no.: B03014449C) ↩

-

Balestier, J., & Montgomerie, W. (1841, December 2). From an unpublished journal of a residence at Singapore: During part of 1840 & 41. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Thomson, J.T. (1850). General report on the residency of Singapore, drawn up principally with a view of illustrating its agricultural statistics. The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, Vol. IV, 134–143, p. 140. (Call no.: RRARE 950.05 JOU; Microfilm no.: NL25791) ↩

-

Pwee, T. (2015, July–September). The French can. BiblioAsia, 11 (2). Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Pineapple industry. (1908, September 2). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

C.D. (1908, July 25). Planting in Singapore. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

For more information about Tan Kah Kee, see Tan, B., & Wee, J. (2016). Tan Kah Kee. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

First pineapple canning factory in Federated Malay States. (1922, June 20). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

For more information about Lee Kong Chian, see Nor-Afidah Abd Rahman & Wee, J. (2011). Lee Kong Chian. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

For more information about Tan Chay Yan, see Sutherland, D. (2009). Tan Chay Yan. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

[Untitled]. (1910, August 11). The Straits Times, p. 6; Tampenis Plantations, Ltd. (1910, September 10). The Straits Times, p. 7; The Sembawang sale. (1910, November 11). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Bukit Sembawang. (1912, July 10). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 4; Singapore United Rubber Plantations Limited. (1912, December 11). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The shortage of land. (1952, August 23). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Companies plan to build and sell. (1954, November 29). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩