Chinese Graphic Artists in Pre-war Singapore

Advertising art began playing a bigger role in the economy after several talented graphic artists moved from China to Singapore from the 1920s onwards. Lee Chor Lin highlights their works.

As Singapore became one of the most dynamic global cities during the first half of the 20th century, it began to attract new migrants due to the myriad opportunities and lifestyles offered by a modern and booming metropolis. By the late 1920s, established and novice artists from China began converging in Singapore due to the job opportunities as well as the instability back home caused by natural disasters, incessant civil wars and Japanese aggression. As a result, in the years leading up to the fall of Singapore in February 1942, the art scene here was thriving and new styles of art were being created.1

Print advertising production also flourished during this period because the demand for news and information led to an exponential growth in the publishing industry, powered by large-scale printing technology.

Singapore’s pre-war economy, comprising small businesses involved in trade, manufacturing and publishing, created a demand for artistic input as these companies sought to do branding, brand differentiation and product communication. Graphic artists who were proficient in Chinese and English were able to capture a culturally pluralistic marketplace.

Chinese graphic artists, trained abroad as well as locally, were now able to combine the vividness of images with the power of the written word to entice both consumers and customers in Singapore’s new mercantilist economy. This was an area of artistic endeavour that has hitherto been overlooked.

Chinese Advertisement Art in Singapore

Newspapers and magazines were a significant platform for companies looking to reach consumers. By 1932, the combined circulation of the five major Chinese dailies in Singapore exceeded 48,000, this in a community of only 418,000 people.2 In addition to the dailies, readers in Singapore had a choice of evening papers, tabloids and magazines.

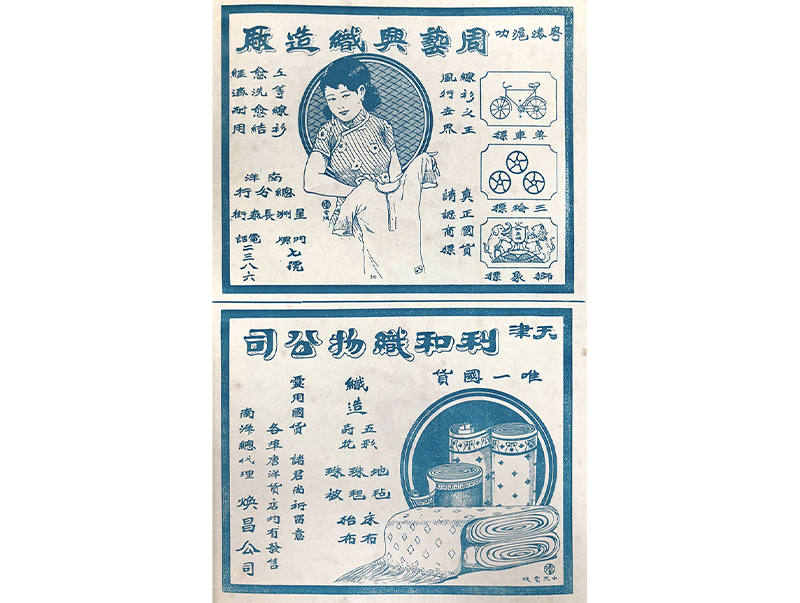

However, newspapers and popular magazines were not the only channels for brands to reach consumers; there were also paid advertisements in school yearbooks and those produced by clans and guild associations. By the early 1940s, there were about 173 Chinese-medium schools in Singapore, with the more established ones – such as Tuan Mong (端蒙學校), Chinese High (南洋華僑中學) and Catholic High (公敎中學) – regularly publishing annual reports and graduation books for students. These were often funded through donation drives by the schools’ board of directors and parents, whose businesses bought advertising slots and pages in the publications to help support their production.

Yearbooks of trade guilds and clan associations were even more strategic avenues than school publications for advertisements. Here, the readership would be highly selected and targeted, exposed to product placement as well as being attuned to signals of the advertisers’ financial standing, since slots were charged by size.

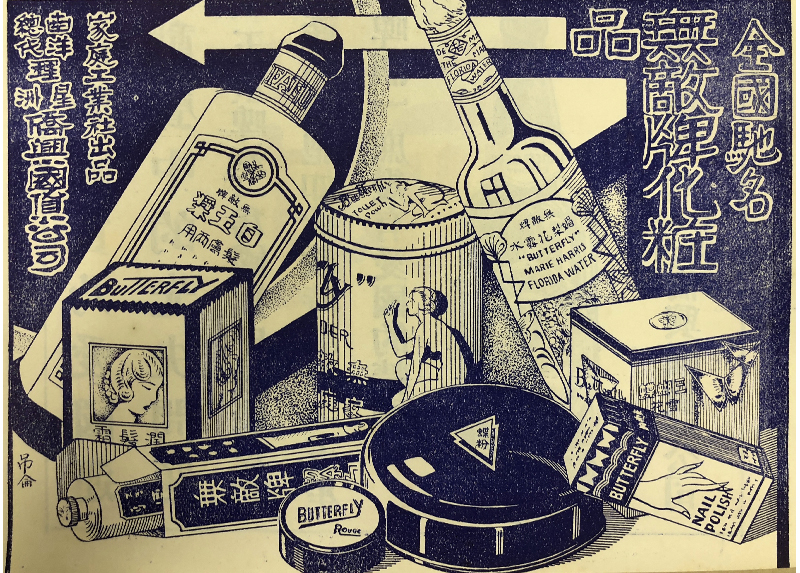

Some of the more impressive art works appeared in the commemorative books of trade associations. For example, those by the Singapore Dried Goods Guild (星洲雜貨行) published in the 1950s, for instance, featured meticulously rendered illustrations.

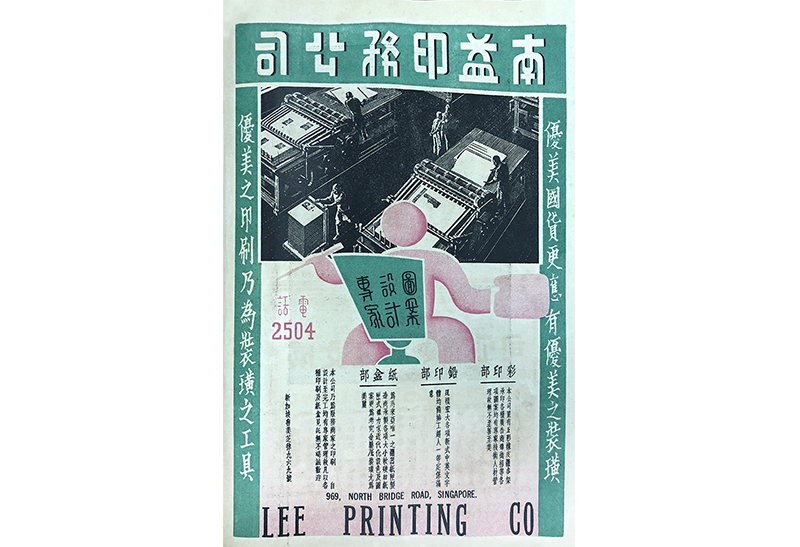

Two publications of great research value in this area were published for Chinese national trade fairs in 1935 and 1936, where artists were engaged to design and manage stall booths and the exhibition catalogues. The latter featured beautiful and elaborate lithographs interspersed with long textual chapters of meeting proceedings, and industry and trade essays. Lee Printing, one of the companies in Lee Kong Chian’s vast business empire, took the first page of the 1935 catalogue to showcase its printing services and graphic design capability.

The repertoire of most studios in the pre-war years also included outdoor signages. Walls could be used for advertising, particularly those that were owned privately. In 1938, at their Third Annual Exhibition, members of the Society of Chinese Artists (華人美術研究會) posed for a photograph on the grounds of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce with a gigantic wall advertisement of the neighbouring Lim Shing Hong Jewellery (林盛豐金莊) in the background.

Although it is difficult to ascertain the number of people involved in graphic design and the making of print advertising, there were enough of them to form a society of their own. The Singapore Commercial Art Society was formally established on 28 February 1937; by the following year, it had organised sketching trips. Following the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in July 1937, the society also actively contributed to the China War Relief Fund.

Artists and Their Studios

While the buoyant economy of pre-war Singapore provided opportunities for artists to live and work in the city, art-making remained a challenging vocation for most artists. Few were able to paint fulltime so many held other jobs to make ends meet.

A number of them taught art in the Chinese schools that proliferated at the time which were founded on the Modernist belief that art and physical education were integral to building good character. Otherwise, these artists would work in the “commercial” sector – drafting shop drawings for architects, designing furniture and printing textile. Many found jobs more easily in companies creating advertising artwork.

An example of the phenomenon is artist Xu Qigao (許奇高) from Jieyang city in Guangdong province. A Tokyo-trained Modernist who had already made a name for himself in China, Xu came to Singapore to escape violence inflicted in his hometown by the Kuomingtang (KMT) government between the late 1920s and the early 30s.

In 1936, Xu staged an exhibition in Singapore, which was sponsored by Chima Studio (“Red Horse”) (赤馬画室).3 While he was here, Xu lodged with his aunt and uncle. His cousin Tan Teo Kwang (陳潮光) remembered seeing Xu drawing advertisements. (Xu lived with the Tans until he returned to China in 1947.)4 His stint with Chima shows that even established artists had to find ways to supplement their fine-art endeavours.

While Xu’s commercial work has yet to surface, we do have the creations of four of his contemporaries – Tchang Ju-ch’i (張汝器), Xu Diaolun (許釣綸), Leong Siew Tien (梁小天; Liang Xiaotian) and Chong Beng Si (鍾鳴世). Their signed works enhance our understanding of the nature of art-making and their connections to Singapore’s pre-war business scene.

Ju Chi Studio (汝器画室) and The United Painters (朋特画室)

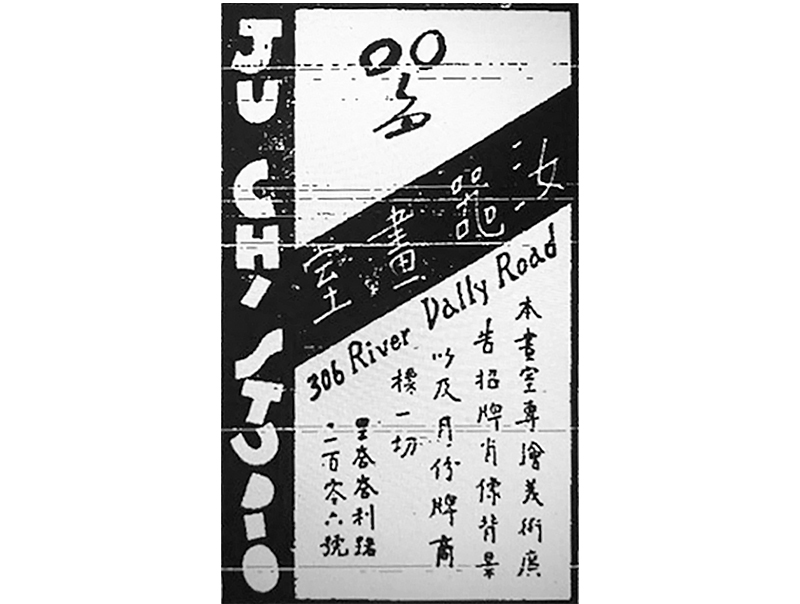

One of the most prominent and active artists in pre-war Singapore, Tchang Ju-ch’i had his life brutally cut short by World War II in 1942. A student at the Shanghai Academy of Art, Tchang left for France to pursue art but had to turn back after running out of funds. It is unclear when he arrived in Singapore but by late 1928, he had certainly settled down here and by the following year, he was involved in a number of projects.

Apart from teaching art at Yeung Cheng (養正學校) and Tuan Mong schools, and a small artist collective called The Painting Society (繪畫研究會),5 Tchang was also picture editor and editor of Sin Chew Jit Poh’s (星洲日报) weekly supplement.

At the invitation of Chen Lien Tsing (陳鍊青), the chief editor of Lat Pau (叻报), Tchang redesigned the masthead of its literary section, Coconut Grove (椰林; Yelin), and subsequently guest-edited Yehui (椰暉), Lat Pau’s illustrated weekend pictorial, for half a year between October 1930 and April 1931. During this period, Tchang made a name for himself as an accomplished cartoonist and when he opened Ju Chi studio (汝器画室) in early 1930, it was widely publicised in both Lat Pau and Sin Chew Jit Poh.

In 1934, Tchang and U-Chow (莊有釗) set up The United Painters (朋特畫社) at 181 Tank Road, offering a suite of services such as advertisement graphic design and painting, oil painting, sculpture and badge design (U-Chow, also known as Chong Yew Chao or Chuang Yew Chao, was married to Tchang’s first cousin).

The pair worked well together. Tchang’s good-natured personality and connections with Chinese businessmen worked hand-in-glove with U-Chow’s forte – carpentry and light construction which were useful for interior decoration and large-scale structures. In May 1937, when Singapore was mobilised to celebrate the coronation of King George VI, The United Painters was commissioned to erect illuminated arches on Carpenter Street.6

As their business expanded, Tchang and U-Chow were enlisted to work on large projects. In November 1939, the duo – together with Lim Hak Tai, principal and founder of the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) – designed the Yunnan-Burma Railway Photography Exhibition, which was organised by the China Relief Fund. The clean and modern design featuring a series of V-shaped hanging frames won them a rare mention in the press.7

Their design for the expansion and renovation of the Astra cinema in the Royal Air Force Changi Airbase was equally impressive.8 Tchang continued to be a sought-after designer, helming the design and installation committees of prestigious trade fairs, China War Relief fundraisers and art exhibitions as well as becoming the founding president of the Society of Chinese Artists in September 1935.

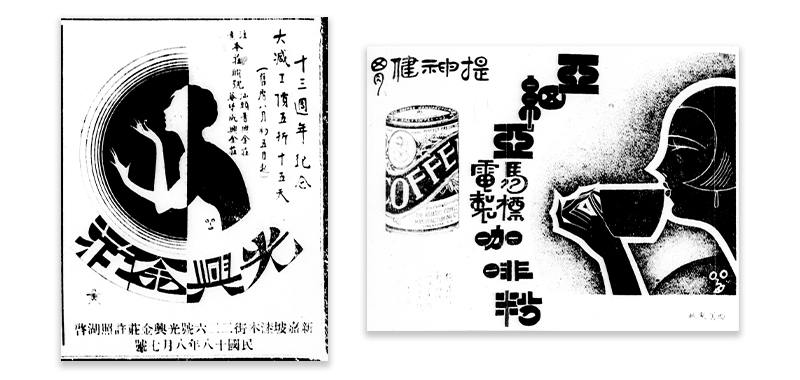

Tchang was also prolific as an illustrator and designer, and left behind a large body of work in print. His major clients featured in Lat Pau and Sin Chew Jit Poh included Kwang Heng Goldsmiths (光興金莊), Asiatic Coffee and Long Long Laundry Blue.

While Tchang pursued a more conventional style for Long Long’s laundry detergent, his works for Kwang Heng Goldsmiths and Asiatic Coffee demonstrate his strong grasp of geometricised shapes with clean lines, the clever of use of silhouettes as well as the inclusion of black and white contrasts.

Instead of using brush calligraphy in the traditional style to render the Chinese characters of his main headings, Tchang would hand draw characters in his unique style. The characters were quirky, elegant and usually tilted slightly to accentuate his handiwork. His graphic style is unique and recognisable, and with his assistant illustrators such as Tsou Chin Hai (周金海), a distinctive house style for the studio can be discerned.

During his editorial stint at Lat Pau’s Yehui, Tchang had to source for and produce content to fill the pictorial weekend supplement, a two-page spread. He would also enter design competitions organised by international brands handled by British agents.

Tchang signed off most of his works with 器 (qi), the last character of his name. The four 口 (“mouth”) in the character would be transformed into a doodle with a comic face. Like many of his illustrations, the signature is immediately recognisable and instrumental in the identification of his works, now scattered in the advertising sections, supplements and section mastheads of many newspapers and magazines.

Xu Diaolun (許釣綸)

Even after two years of intensive research, not much information about Xu Diaolun (許釣綸) has surfaced. However, the evidence suggests that Xu may have been a high-profile person in a number of social circles in Singapore – as an art teacher in Ai Tong School (爱同學校), a founder of the Zhao’an Association (詔安會館), a member of the Khoh Clan Association (星洲許氏高陽公會), the main driving force behind the formation of the Singapore Commercial Art Society, a member of the Hokkien Association Executive Committee (福建會館常務委員會), an activist supporting China in its war against Japan, and one of the proponents of a public library (大眾圖書館).9

In a commemorative publication by Ai Tong School on its 25th anniversary in 1937, Xu was described as a 33-year-old Hokkien who had previously worked as a director at the Education Department of Dongshan, Fujian (福建东山). His essay titled “圖畫科的教學理論和實際” (Teaching Art: Theory and Practice) appears in this publication and demonstrates his knowledge as an experienced art educator.10 In 1933, he had been involved in the short-lived communist rebellion in Fujian and he appeared on KMT’s wanted list of rebels.11 That explained how Xu ended up in Singapore, how he quickly became involved in a number of progressive social and patriotic activities here, and how he secured a position in the well-established Hokkien school, Ai Tong.

Above all, Xu was an accomplished graphic artist who went by his nom de plume 吊侖, a homonym of his real name Diaolun (釣綸). He was a versatile artist, like many of his colleagues, and could accommodate the different tastes and demands of clients.

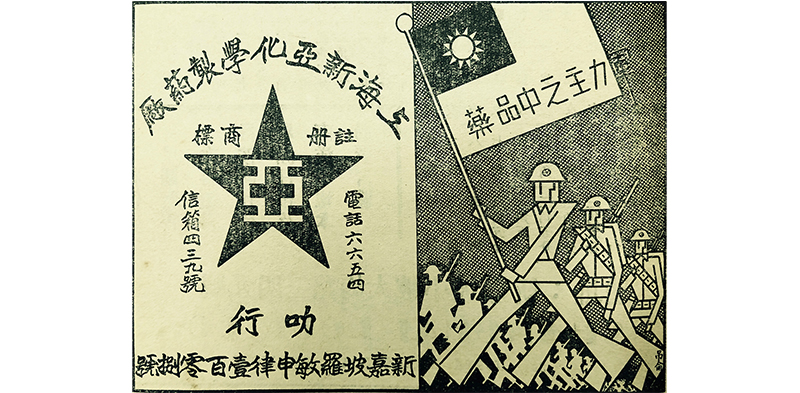

In the Ai Tong School publication, Xu contributed an advertisement featuring toy-like soldiers armed with bullets and rifles on the march, symbolising the strength of its advertiser, Shanghai New Asiatic Pharmaceutical Company (上海新亞化學製藥廠).12 Xu seemed to have made inroads into the Shanghai network in Singapore as his other client was the Shanghainese-owned Khiauw Hing (僑興), a company that sold chemical products and liquor from China.

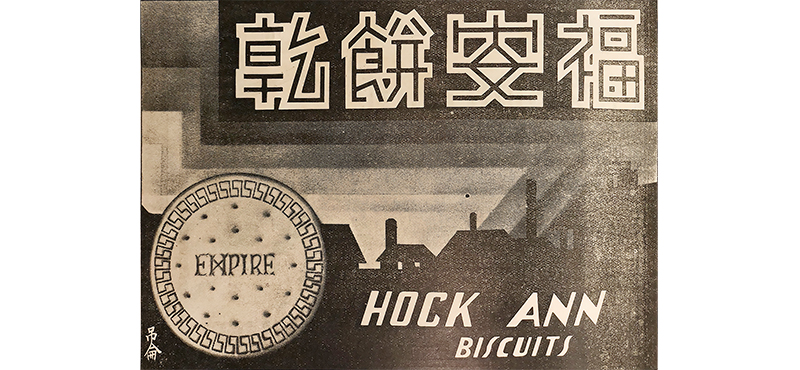

In Chinese High School’s 1938 yearbook, Xu worked on an advertisement for local biscuit factory Hock Ann. He also took part in competitions and in 1935, his illustration for Tolley Brandy won first prize in the brand’s annual advertisement illustration contest.

Xu’s works are characterised by minute articulation and detailed embellishment. He drew women in long ankle-length tight-fitting cheongsam, seated tilted at an angle to accentuate their svelte figures. His lines are clean and slightly rigid, while his calligraphy is stately and seal-like. There is no mention of him in the Chinese press from around 1941, but his works in advertising illustrations continue to remind us of his artistry.

Xiaotian Huashi (小天畫室)

Leong Siew Tien (Liang Xiaotian) came to Singapore, possibly via Hong Kong, and later established the studio Xiaotian Huashi (小天畫室) on Cross Street in the 1930s. In the late 1920s, Leong was part of the Kreta Ayer literati scene. He was an urban legend, writing and drawing satirical cartoons for the Nan Fan Periodical (南薰三日刊; Nanxun sanrikan) , which had a strong following among the Cantonese community living in the area.13

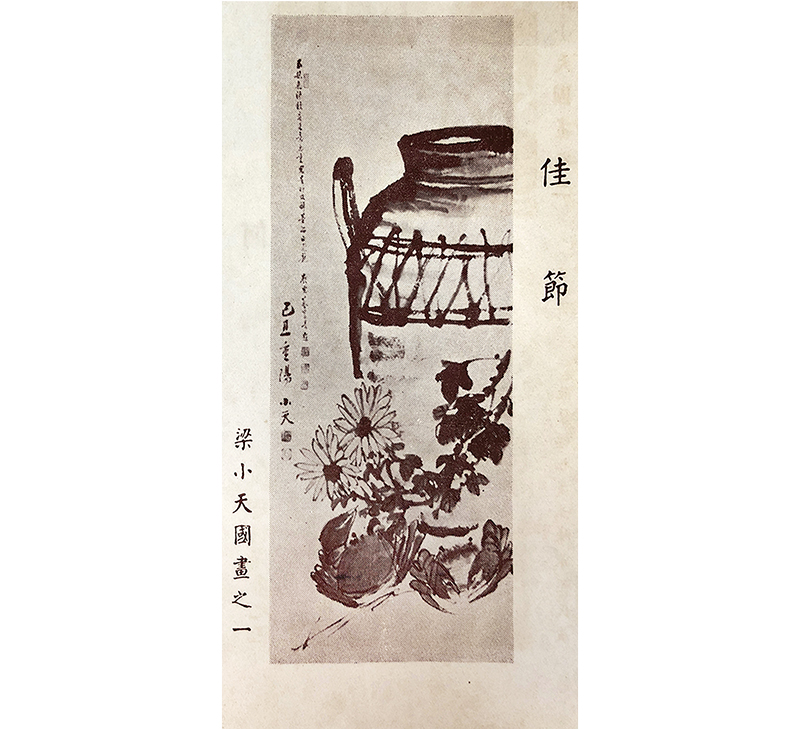

Leong’s versatility in Chinese ink and watercolour painting is documented in publications of the Chung Shan (Clan) Association (中山會館) and the Society of Chinese Artists, where he was a member.

While his watercolour works are competently executed, Leong’s classical training is visible in his Chinese-ink works, which recall the Shanghai School (上海画派) influence, characterised by powerful calligraphy-style brushwork and dynamic compositions.

In 1948, Leong joined a group of old-school scholars, calligraphers and Shanghai-influenced artists to form the Seal and Inscription Society (金石学会; Jinshi Xuehui), a hobbyist gathering dedicated to the study and appreciation of ancient inscriptions, etymology, calligraphy and seal-carving.

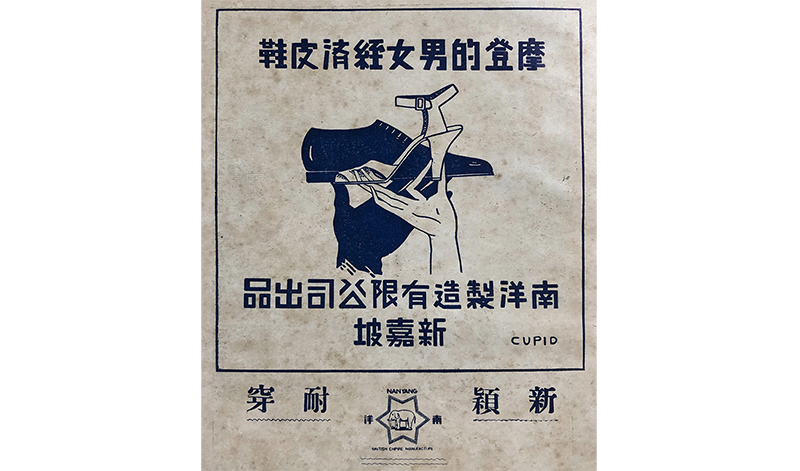

Professionally, Leong worked as a fulltime graphic artist in his own studio. The studio provided a range of services, including head-shot portrait painting on ceramic plaques (generally for tombstones, advertising illustrations and lithograph plate-making).

The signatures that Leong left on his commercial works suggest that he focused on three areas – illustration, for which he signed off as 小天繪製 (Xiaotian huizhi); lithograph plate-making, where he used 小天製版 (Xiaotian zhiban); and photo-engraving, when he was known as 小天電版 (Xiaotian dianban).

Leong’s commercial art features old Shanghai-style composition made popular at the turn of the 20th century, in which products or cheongsam-clad ladies were meticulously drawn using clean lines, perfect for monochrome printing, while text was rendered in striking classic seal characters. He was also an active member of the Singapore Commercial Art Society until the late 1970s.

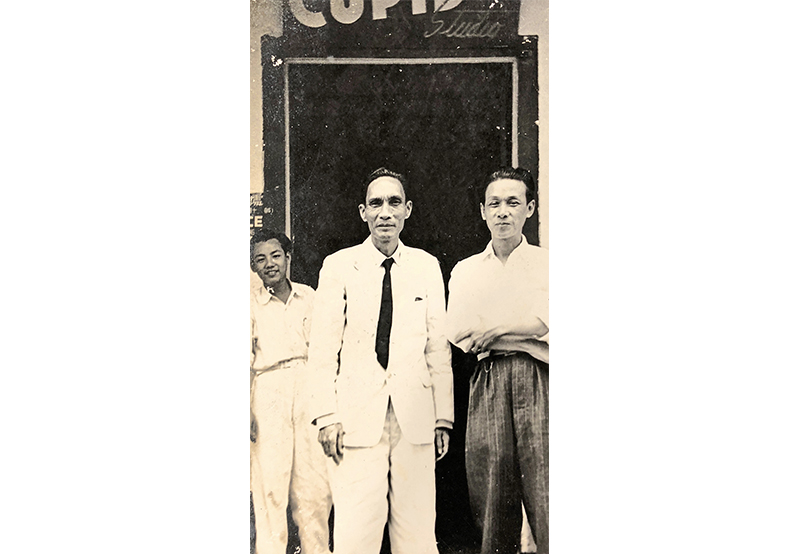

Cupid Studio (天使畫室)

Established by Chong Beng Si (鍾鳴世) around 1937, Cupid Studio operated from a shophouse at 270 Telok Ayer Street, strategically positioned to serve the Chinese businesses in the vicinity of Robinson Road, Cecil Street, Telok Ayer, Amoy Street and Club Street.

Chong was also assistant to Lim Hak Tai, principal and founder of NAFA. Chong handled administrative and estate-related matters for the school in addition to teaching Western art. He was also one of the earliest members of the Society of Chinese Artists. And, like many of his fellow contemporary artists, Chong made his living creating commercial advertisement art.

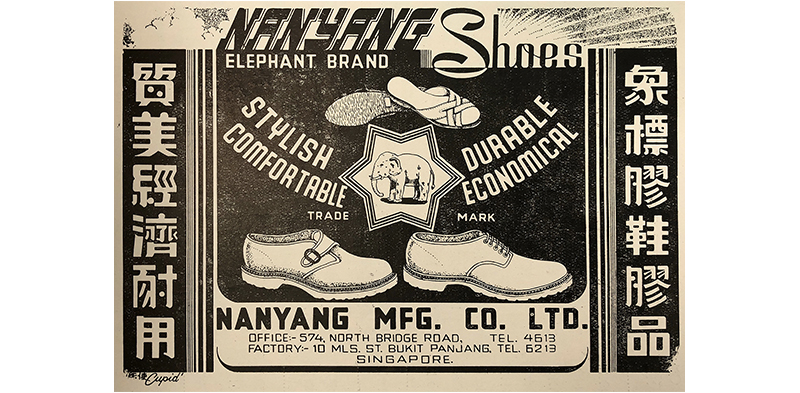

Chong’s clientele included major brands in Singapore such as the Nanyang Elephant brand of rubber shoes made by Nanyang Manufacturing, which belonged to Lee Kong Chian; Hua Hong Manufacturing (cooking oils); and Yeo Hiap Seng Sauce Factory.

Most of his artworks used formalistic and clear composition where the products were vividly illustrated, with the brands and brand-owners’ names rendered in strong and beautiful Westernised non-calligraphic typography.

Chong deftly created Chinese characters and used decorative elements such as italics, shadowing and sans serif text to complement the non-Chinese letters and words.

In general, Chong’s graphic works display a sure grasp of the Western graphic art sensibility – functional although not necessarily cutting-edge. His fine art works featured in the exhibitions by the Society of Chinese Artists, generally in oil or watercolour, are not stunning but they are competent and pleasing.

Leaving a Legacy

A number of these graphic artists formed the Singapore Commercial Art Society in 1937. In recounting its history, long-time Chairman Siew Suet Pak (邵雪白) remembered the persistence of Xu Diaolun in pushing to form the society.14 Leong Siew Tian and U-Chow were among the artists, either as freelancers or studio owners, who were members.15 The society continued to function well into the 1990s, although new printing technologies and desktop graphic design had made the skills of the society’s members obsolete by then.

Studying the history of art-making in Singapore provides an insight into the workings of Singapore’s economy which, until very recently, was essentially a history of trade and one powered by thousands of small and medium-size businesses, including the individuals who designed, made signages, laid out pages of books, and printed publications for domestic and international publishers and readers.

The story of these graphic artists of a bygone era will contribute greatly to our appreciation of Singapore’s art history as well as its economy, its tenacity and responsiveness to change.

Lee Chor Lin is an art historian and a museum consultant. She was the director of the National Museum between 2003 and 2013 and during her tenure, she transformed the museum and museum scene in

Singapore. She is also a Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow (2019). [Photo by Melisa Teo]

Lee Chor Lin is an art historian and a museum consultant. She was the director of the National Museum between 2003 and 2013 and during her tenure, she transformed the museum and museum scene in

Singapore. She is also a Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow (2019). [Photo by Melisa Teo]

NOTES

-

“Art making in a cultural desert” lecture by Lee Chor Lin on 27 November 2019, part of the lecture series for the exhibition “Living with Ink: The Collection of Dr Tan Tsze Chor” (8 Nov 2019–26 Apr 2020), Asian Civilisations Museum; Lee, C.L. (2021, June). Colonising the coconut groves: Artistic legacies of British colonial Malaya. (Post) Colonialism and Cultural Heritage. Humboldt Forum, Berlin. ↩

-

See Table 4.6 circulation rates of Singapore newspapers, 1919–1932 in Kenley, D.L. (2003). New culture in a new world: The May Fourth Movement and the Chinese diaspora in Singapore, 1919–1932 (p. 101). New York: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 959.57004951 KEN). For Singapore’s population of the period, see Table 5.14, percentage distribution of Singapore’s total population by ethnic group in Pan, L. (Ed.). (1998). The encyclopedia of the Chinese overseas (p. 200). Singapore: Archipelago Press. (Call no.: RSING 304.80951 ENC) ↩

-

Chima (“Red Horse”) Art Studio, run by Xie Song An (謝松盫), was an established company by the early 1930s. Xie himself made a donation of $200 (in Chinese currency) in 1932 towards relief funds for the flood in Shanghai while the staff contributed half a month’s salary voluntarily. It is unclear if Xie was himself an artist, but he was an active member of the Chinese community in Singapore, making regular cash donations and serving on the decorating committee for the high-profile fundraiser of the China Relief Fund in 1938. ↩

-

Personal correspondence with Tan Teo Kwang, c. 2017–2018. ↩

-

第19页 广告 专栏 1. (1929, March 16). 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. [The same advertisement appeared in the 1, 8, 13, 19, 20 and 21 March 1929 editions of the newspaper.] ↩

-

Singapore & coronation reflections. (1937, May 10). The Malaya Tribune, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

星華籌賑大會主辦南新洋國民商報報滇緬公路攝影展覽會舉行隆重開幕高總領事主持開幕禮稱觀此影展可加强抗戰信念主席李光前謂此影展會足以發揚吾民族復興精神會場佈置由美術專家多人設計極爲精緻. (1939, November 25). 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

漳宜軍人影院重新改建. (1939, December 8). 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

大眾圖書館不久將在本坡出現. (1937, January 14). 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

許釣綸 (Xu, D.L]. (1937). 圖畫科的教學理論和實際 (p. 65). In 愛同學校二十五週年特刊 [Ai Tong School 25th Anniversary Commemorative Publication]. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

福建事变/闽变. See 杨伯凯 123, 参加‘福建事变’的农工当主要人物简介. Retrieved from 中国农工民主党福建省委员会 website. ↩

-

Shanghai New Asiatic Pharmaceutical Company, founded in 1926, was one of China’s leading nationalist entrepreneurial efforts in the first half of the 20th century, and a current major pharmaceutical player in Shanghai. ↩

-

梁山. (1983, July 14). 牛车水的旧文. 联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], p. 39; 梁山. (1984, December 17). 新加坡早期的小报. 联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], p. 40. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

First commercial art course graduation exhibition: Officially opened by Inche Sha’ari bin Tadin. (1972). Singapore: Singapore Commercial Art Society. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

美術廣告研究會會員,會選出第一屆職員. (1939, July 4). 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩