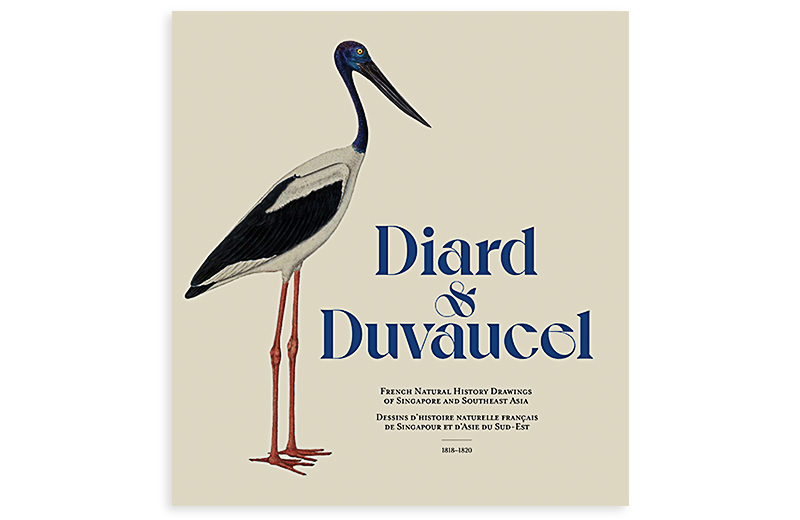

French Impressions: 19th Century Natural History Drawings of Singapore and Southeast Asia

A little-known collection from 1818 to 1820 commissioned under the watch of two French naturalists sheds light on the early study of the region’s flora and fauna.

Diard & Duvaucel: French Natural History Drawings of Singapore and Southeast Asia 1818–1820 is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 508.0222 DIA and SING 508.0222 DIA) and for sale at all major bookstores, including Epigram’s online store at epigrambookshop.sg.

Diard & Duvaucel: French Natural History Drawings of Singapore and Southeast Asia 1818–1820 is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 508.0222 DIA and SING 508.0222 DIA) and for sale at all major bookstores, including Epigram’s online store at epigrambookshop.sg.

Until recently, most people would not have heard of the two Frenchmen, Pierre-Médard Diard and Alfred Duvaucel, who accompanied Stamford Raffles on his maiden trip to Singapore on 28 January 1819.1 Fewer still would know that these two young naturalists collected specimens and worked with artists to create drawings of animals and plants at the various locations they ventured to, including Singapore and the surrounding region as far away as India.

Today, these 117 lifelike colour illustrations – mostly of birds and artfully drawn by unnamed local artists − join the more widely known natural history drawings commissioned by William Farquhar when he was British Resident and Commandant of Melaka between 1803 and 1818. Together, these collections provide an important insight into the development of science and the study of natural history of this region in the early 19th century.

What makes the Diard and Duvaucel collection especially significant is that it contains what is possibly the first illustration of an animal that is native to Singapore and Southeast Asia − the Spiny Turtle. The handwritten annotation on the drawing clearly proclaims “isle de Singapour” or “island of Singapore”, stamping our claim on the origins of this now-endangered species.

Although the relationship between Raffles and the two naturalists ended abruptly, with the Frenchmen dismissed and their precious specimens and research confiscated, the drawings found their way safely back to France where they reside today in the collections of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. Thanks to the generosity of the museum, the National Library, Singapore, was given permission to put up the digitised images of the collection on its BookSG portal for the public to access in 2020.2

More recently, all 117 illustrations have been published in a hardcover book titled Diard & Duvaucel: French Natural History Drawings of Singapore and Southeast Asia, 1818−1820. Co-published by Epigram, the Embassy of France in Singapore and the National Library together with several key partners, the introductory essays and detailed captions accompanying the stunning illustrations have been written by a team of scientists and curators based in Singapore, Paris and Spain.

We can’t be certain if Diard and Duvaucel were the first Frenchmen to have stepped on Singapore soil, but certainly they are now the first to be part of our documented history. These brave men who left the comforts of their homeland blazed a trail for other French citizens − explorers, planters, merchants and missionaries − who followed in their wake. That French presence continues in Singapore today, represented by a 20,000-strong community who are part of the city’s commercial and cultural scene.

Nº 11: Banded Woodpecker

Chrysophlegma miniaceum

This woodpecker with a yellow-tipped crest can still be spotted in Singapore today. The specimen portrayed in this drawing, however, is more likely from the Malay Peninsula or Sumatra, where Diard and Duvaucel might have collected it. The bird had already been described scientifically about 50 years before Diard and Duvaucel travelled to the region.

This woodpecker with a yellow-tipped crest can still be spotted in Singapore today. The specimen portrayed in this drawing, however, is more likely from the Malay Peninsula or Sumatra, where Diard and Duvaucel might have collected it. The bird had already been described scientifically about 50 years before Diard and Duvaucel travelled to the region.

Nº 34: Green Broadbill

Calyptomena viridis

On 1 June 1820, Stamford Raffles wrote about the Green Broadbill in his Descriptive Catalogue of a Zoological Collection thus: “Found in the retired parts of the forests of Singapore and of the interior of Sumatra.” There are two depictions of this broadbill in the collection. They are nearly identical, differing only in the composition of the tuft of feathers on the forehead. In both drawings, the birds are male, as indicated by the small yellow spots above their eyes. From Raffles’ catalogue entry, it can be inferred that he must have procured at least two specimens, one from Singapore and another from the environs of Bencoolen (Bengkulu) in Sumatra. Diard, Duvaucel and William Jack (a botanist working with Raffles) could have collected the Singapore specimen during their visit in 1819. This species has the distinction of being the first bird from Singapore to be given a scientific name.

Nº 11: Nº 67: Javanese Lapwing

Vanellus macropterus

The lapwing depicted in this drawing used to occur in a few places in Java. Today, it is thought to be extinct and reports of sightings in Sumatra have not been substantiated thus far. Stamford Raffles or Diard and Duvaucel might have bought a specimen in a market, which would not have been an unusual practice then. Although the species had already been described from a bird in the collections of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, that specimen has no connection with either Diard or Duvaucel.

The lapwing depicted in this drawing used to occur in a few places in Java. Today, it is thought to be extinct and reports of sightings in Sumatra have not been substantiated thus far. Stamford Raffles or Diard and Duvaucel might have bought a specimen in a market, which would not have been an unusual practice then. Although the species had already been described from a bird in the collections of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, that specimen has no connection with either Diard or Duvaucel.

Nº 7b: Hanuman Langur

Semnopithecus entellus

When Duvaucel was staying in Chandernagor (Chandannagar) in West Bengal, India, langurs were quite a common sight, especially at the start of winter. Local Bengalis consider the monkey species depicted in this drawing as sacred because its black face and hands resemble those of the Hindu monkey god Hanuman. According to accounts, every time Duvaucel had a chance to point a gun at one of these langurs, the people around him would start making loud noises, causing the animals to scatter. One day, Duvaucel went to the holy town of Gouptipara (Guptipara) in the Hooghly district, not far from his home, where dozens of langurs were resting in the trees. Before Duvaucel could get hold of a specimen, however, he was surrounded by a dozen devotees intent on stopping him. On his way home, he noticed a beautiful female Hanuman Langur; unable to resist the temptation, he shot her. She died, just after trying to save her baby by hiding it among the leaves of a tree. Perhaps Duvaucel felt sorry for what he had done. The female monkey is immortalised in this drawing, which was reproduced in Histoire Naturelle des Mammifères, a grand illustrated work on recently discovered mammals by his uncle (by marriage) Frédéric Cuvier in 1825.

When Duvaucel was staying in Chandernagor (Chandannagar) in West Bengal, India, langurs were quite a common sight, especially at the start of winter. Local Bengalis consider the monkey species depicted in this drawing as sacred because its black face and hands resemble those of the Hindu monkey god Hanuman. According to accounts, every time Duvaucel had a chance to point a gun at one of these langurs, the people around him would start making loud noises, causing the animals to scatter. One day, Duvaucel went to the holy town of Gouptipara (Guptipara) in the Hooghly district, not far from his home, where dozens of langurs were resting in the trees. Before Duvaucel could get hold of a specimen, however, he was surrounded by a dozen devotees intent on stopping him. On his way home, he noticed a beautiful female Hanuman Langur; unable to resist the temptation, he shot her. She died, just after trying to save her baby by hiding it among the leaves of a tree. Perhaps Duvaucel felt sorry for what he had done. The female monkey is immortalised in this drawing, which was reproduced in Histoire Naturelle des Mammifères, a grand illustrated work on recently discovered mammals by his uncle (by marriage) Frédéric Cuvier in 1825.

Nº 2: Spiny Turtle

Heosemys spinosa

“The island of Singapore” or “isle de Singapour” states the annotation on the drawing. This is quite a remarkable statement to make at a time when Singapore had only just entered the public consciousness in Europe because of Raffles and the East India Company. Diard and Duvaucel were in Singapore between January and February as well as May and June 1819, during which time they could have observed the young turtle represented in this drawing. Although no date was written on the paper, this may well have been the first illustration of an animal found in Singapore. The Spiny Turtle is found widely across Southeast Asia, usually in lowland rainforests near rivers or streams. The half-completed aspect of some of the drawings, like this example, suggests that the artist (or artists) working in the field with Diard and Duvaucel were under pressure to record time-critical aspects of the animals. This is particularly obvious with the drawing of the Spiny Turtle – the identical left legs could have been added later.

“The island of Singapore” or “isle de Singapour” states the annotation on the drawing. This is quite a remarkable statement to make at a time when Singapore had only just entered the public consciousness in Europe because of Raffles and the East India Company. Diard and Duvaucel were in Singapore between January and February as well as May and June 1819, during which time they could have observed the young turtle represented in this drawing. Although no date was written on the paper, this may well have been the first illustration of an animal found in Singapore. The Spiny Turtle is found widely across Southeast Asia, usually in lowland rainforests near rivers or streams. The half-completed aspect of some of the drawings, like this example, suggests that the artist (or artists) working in the field with Diard and Duvaucel were under pressure to record time-critical aspects of the animals. This is particularly obvious with the drawing of the Spiny Turtle – the identical left legs could have been added later.

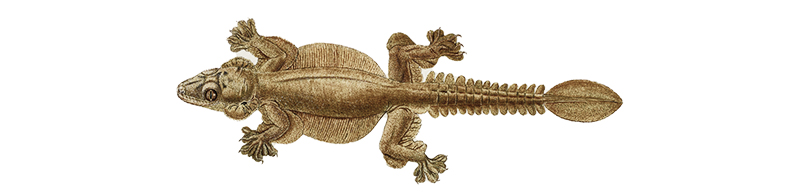

Nº 3: Kuhl’s Gliding Gecko

Gekko kuhli

The specimen portrayed in this drawing was obtained in Sumatra. This conspicuous gecko was first described from Java, where Diard again found it after he left the employ of Stamford Raffles. Kuhl’s Gliding Gecko can also be found in Singapore, where an early specimen was collected and donated to the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris in December 1868 by the French trader Andrew Spooner.

The specimen portrayed in this drawing was obtained in Sumatra. This conspicuous gecko was first described from Java, where Diard again found it after he left the employ of Stamford Raffles. Kuhl’s Gliding Gecko can also be found in Singapore, where an early specimen was collected and donated to the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris in December 1868 by the French trader Andrew Spooner.

Nº 2: Flask-shaped Pitcher Plant

Nepenthes ampullaria

Stamford Raffles collected pitcher plants when he first visited Singapore in early 1819, and these became the first botanical specimens from mainland Singapore. The Scottish botanist William Jack was working for Raffles at the time, but he did not accompany Raffles on this first visit to Singapore and instead remained at Prince of Wales Island (Penang). When Raffles returned to Penang from Singapore, these botanical specimens were passed to Jack for study. Jack named one of the species after Raffles – Nepenthes rafflesiana Jack (better known as the Raffles’ Pitcher Plant) – to honour the collector. What is depicted in this drawing though is the Nepenthes ampullaria. These names were only published in 1835, years after Jack’s death in 1822 and based on research and drawings that were sent back to England. Diard and Duvaucel would have known about Jack’s work, although this painting was probably drawn from a separate specimen at a later date.

Stamford Raffles collected pitcher plants when he first visited Singapore in early 1819, and these became the first botanical specimens from mainland Singapore. The Scottish botanist William Jack was working for Raffles at the time, but he did not accompany Raffles on this first visit to Singapore and instead remained at Prince of Wales Island (Penang). When Raffles returned to Penang from Singapore, these botanical specimens were passed to Jack for study. Jack named one of the species after Raffles – Nepenthes rafflesiana Jack (better known as the Raffles’ Pitcher Plant) – to honour the collector. What is depicted in this drawing though is the Nepenthes ampullaria. These names were only published in 1835, years after Jack’s death in 1822 and based on research and drawings that were sent back to England. Diard and Duvaucel would have known about Jack’s work, although this painting was probably drawn from a separate specimen at a later date.

NOTES

-

Danièle Weiler, “Stamford Raffles and the Two French Naturalists,” BiblioAsia 16, no. 2 (Jul–Sep 2020). ↩

-

Figures peintes d’oiseaux [et de reptiles], envoyées de l’Inde par Duvaucel et Diard (Painted depictions of birds [and reptiles], sent from India by Duvaucel and Diard). (From BookSG). ↩