Mother Island: Finding Singapore's Past in Pulau Lingga

Singapore’s history is closely intertwined with that of Lingga’s. The kings that once reigned from its shores played a pivotal role in the fate of the Malay world, including the birth of modern Singapore, as Faris Joraimi reveals.

In a half-forgotten corner of Telok Belanga (officially rendered as Telok Blangah), sandwiched between Bukit Purmei and Kampong Bahru Road, lies the tomb of the last king of the Riau-Lingga Sultanate, Sultan Abdul Rahman Mua’zzam Shah II (r. 1883–1911). Deposed by the Dutch in 1911 after refusing to sign a treaty that would effectively strip him of all power, he fled to Singapore where he lived in exile until his death in 1930.

Today, many Singaporeans associate the Riau islands, now part of Indonesia, with Batam’s massage parlours and Bintan’s more sanitised resorts. Fewer, though, have any inkling of just how much Singapore is bound to this archipelago by ties of history, economics and culture. Who remembers, for instance, that both Singapore and the Riau-Lingga archipelago were once part of the same maritime empire: the old Sultanate of Johor that emerged after the fall of Melaka to the Portuguese in 1511? Modern Singapore came into being ultimately with the dismemberment of this realm in 1824, when the Anglo-Dutch Treaty divided the Malay World between the British and the Dutch.1

A Trading Power

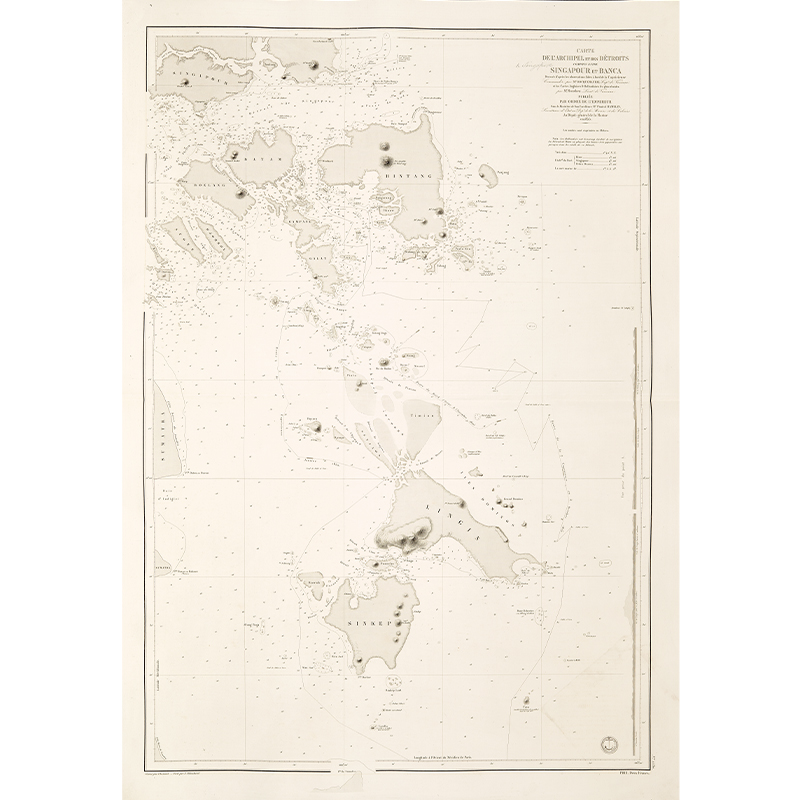

The name “Riau-Lingga” is a collective geographic expression for an archipelago of islands located south of Singapore and east of Sumatra. The archipelago includes familiar places such as Bintan and Batam, but also other isles, such as Pulau Lingga and Pulau Penyengat, that once loomed large over the region. Riau-Lingga referred to the kingdom’s (uneasy) system of dual government: Riau being the domain of the Bugis chiefs centred around Bintan and Pulau Penyengat, while Pulau Lingga served as the sultan’s headquarters.

This joint Malayo-Bugis rule dates back to the time of the old Johor Sultanate. It was a system that sustained the polity following the turbulent wars that erupted after Sultan Mahmud Shah II’s (r. 1685–99) violent assassination.2 Having died without a male heir, Sultan Mahmud II was the last in the line of a dynasty of rulers that had held kingship over Melaka (founded c. 1400), before the Portuguese invasion in 1511 forced the court to flee south and re-establish its rule on various sites along the Johor river.

Later, racked by rival claims to the throne following Mahmud II’s gruesome death, the kingdom was restored to order under the new Bendahara Dynasty with the backing of Bugis warrior-chiefs. Bearing the title “Yang Dipertuan Muda” (viceroy), the Bugis chiefs built up old Johor into a formidable regional power, drawing upon their military and economic dominance across the Malay seas.

Association with the Malay court gave the Bugis newcomers prestige and also a strategic base to conduct their economic activities.3 In the words of historian Carl Trocki, the Bugis exploited the Johor Sultanate but also preserved it.4 The Malay rulers, though sovereigns de jure, became increasingly less involved in the running of their kingdom. That said, they remained crucial to its legitimacy through the force of daulat – a mystical aura of royal authority that preserved the realm – believed to inhabit their bodies.

Old Johor reached its height in the 18th century when it was ruled from the port city of Riau, on the Carang River in Bintan. Stable, prosperous and competitive, it posed a threat to Dutch trading interests in the region.5 This rivalry led to an all-out war in 1784 that witnessed the heroic stand of the Bugis chief Raja Haji Fisabilillah against the European invaders. The Dutch, however, eventually triumphed. They destroyed Riau and extended their influence over the polity.

The echoes of such splendours and struggles can be glimpsed from a seven-hour voyage that begins at the Tanah Merah Ferry Terminal in Singapore and ends at Pulau Lingga, the former kingdom’s royal seat since 1788. Lingga is a land of palaces, forts and tombs, and nearly every royal landmark here bears the imprint of a broader reach.

The Isle of Kings

In 2019, a friend of mine, the researcher and photographer Marcus Ng, invited me on a trip to Lingga. There is no direct route there from Singapore as the ferry from Tanah Merah stops in Tanjong Pinang, the capital of Indonesia’s Riau Islands Province (Provinsi Kepulauan Riau, or “Kepri” for short). Visible across the water is Pulau Penyengat, the tiny island fortress of the former Bugis chiefs. On Pulau Penyengat are the tombs of renowned figures from the history of the sultanate – from Engku Puteri Raja Hamidah, consort of Sultan Mahmud Shah III (r. 1770–1811), to the scholar and chronicler Raja Ali Haji.

As the inter-island transit ferry departs Tanjong Pinang, we enter azure waters girded by white sands with endless coconut palms, pandan plants (screwpine) and casuarina trees. The ferry makes stops at neat coastal kampongs – ordered lines of littoral houses built along the perimeter of tiny isles such as Pulau Benan and Pulau Rejai. It skirts hidden shoals, marked by the half-submerged stilt-roots of bakau (Rhizophora spp.) trees, mangrove islands that rise and sink with the tide.

Near these intertidal forests, people have built traditional fish traps – like the kelong and belat – which recall scenes of old Bedok, Siglap or Pasir Panjang before reclamation and resettlement: the Singapore our parents remember. But the equally prominent broadcast towers and satellite dishes remind us that this is how modern and connected rural life can look like too.

After about five hours at sea, the ferry berths at Sungai Tenam pier, on the northern tip of Lingga. It is another hour’s drive south to Daik, the island’s principal town on its opposite coast. The well-maintained road runs past peaty swamps, pepper gardens and near-century-old gutta percha estates, now nearly indistinguishable from primary rainforest. Before long, Mount Daik and her three peaks emerge into view amid the flat lowlands: a lone cone with sheer faces clawing heavenward.

I had long wanted to visit Daik. Its famed mountain, which rises more than a kilometre above the sea and is oft shrouded by clouds and fog, is memorialised in one of the most renowned Malay pantun:

“Pulau Pandan jauh ke tengah Gunung Daik bercabang tiga Hancur badan dikandung tanah Budi yang baik terkenang juga”6

(Translation: Pulau Pandan lies far out at sea Mount Daik has three peaks The body may dissemble in the earth Good deeds are long remembered)

Daik was where my late maternal great-grandmother was born, more than a hundred years ago. (She had come to Singapore as an adolescent.) The term that the residents of Pulau Lingga give their island: Bunda Tanah Melayu, which roughly translates to “mother of the Malay lands”, resonates with me. Indeed, to this day, Lingga is seen as the spiritual heart of Malay culture. The variety of Malay spoken there is still regarded as the most “refined”. And despite being Indonesian by nationality, the people of Lingga are fiercely proud of their Malay cultural identity, as local resident Rizal, our guide for the trip explained. Much credit goes to him for enabling our access to the sites of interest mentioned in this essay.

Something about the landscape of Lingga, with its soaring peaks visible from distant passing ships, must have suggested it as an ideal spot to found a royal capital. Historians like John Miksic have argued that the Malay kings often built their residences at a point of axis between a mountain or a hill, and an estuary or coast.7 The palace of old Singapura, for instance, was built on the slopes of Bukit Larangan (later Government Hill and then Fort Canning Hill) overlooking the Singapore River.

Lost Istanas and Royal Mosques

The palace that Sultan Mahmud Ri’ayat Shah III built on the Daik River – when he shifted his court from Bintan to Lingga – no longer stands. Neither does the one built by his great-grandson Mahmud Shah IV (r. 1842–57).8 Istana Damnah, completed in 1860 by Sulaiman Badrul Alam Shah II (r. 1857–83), survives only in ruins. What remains are pedestals, pillars and stone staircases suggesting where the demolished halls used to be.

Istana Damnah’s cosmologically strategic site becomes apparent as one approaches it: positioned at the foot of Mount Daik, any potential visitor to the court would have felt a sense of awe at its imposing backdrop. Today, tourists to the area are greeted by a replica of the palace next to the ruins, complete with gardens and a little park with strolling paths and benches.

Daik town still looks and feels like a village in comparison to busy Tanjong Pinang. Its centrepiece is the royal mosque, Masjid Sultan Lingga, whose existing structure dates back to 1909, the third to be built after the previous two were damaged by fires. The first iteration of the mosque was raised in 1800.9 Constructed by Chinese workers brought in from Singapore, the present-day royal mosque has an unassuming Malay vernacular style, complete with signature Malay eaves. Unsurprisingly, it is painted in the regal yellow similar to the royal mosque on Pulau Penyengat.

An elaborate wooden screen greets the visitor upon entry, finely executed by carvers from Jepara in Central Java. Within the mosque is a more grandiose woodwork structure, also of Jepara make: the minbar, or pulpit. Dating back to the 1790s – before the first royal mosque was built – its design bears recognisable Chinese and European elements. The use of pink peonies, tessellated swastikas and baroque foliage departs from what we typically expect to find in a Malay mosque. The swastika, for example, or banji (from the Chinese wansui, 万岁, and the Japanese banzai; both mean “ten-thousand years”) have long been used in Malay and Javanese textiles, woodcarving and metalwork, demonstrating a robust absorption of “Chinese” elements in this region’s visual language.

The pulpit’s local elements are unmistakable: the overhanging eaves on its hexagonal roof are common in Malay construction, and the finial (a crowning ornament or detail) calls to mind the Javanese-style mustaka or kepala som, a carved embellishment found on the roof summits of mosques throughout the Malay world.10 The swirling tendrils and upturned crockets are design motifs found across Malay art, known as awan larat (“meandering clouds”) and sulur bayung (“creeping vine”) respectively.11 The structure’s coat of dark blue, crimson, green and yellow had been freshly painted. During our visit, more repainting works were being done, most notably at the tomb of Sultan Mahmud III. He rests in the burial grounds of the mosque that he had ordered built.

One of his sons, Abdul Rahman I (r. 1811–32), lies buried in a nearby royal cemetery. Enclosed within a low wall painted in that same sacred yellow, the cemetery also contains the graves of two other rulers of Riau-Lingga besides Abdul Rahman I: his successor Muhammad II (r. 1832–42) and Sulaiman Badrul Alam Shah II.

Mahmud III was the last king of a united Johor Sultanate. His death in 1811 threw up two contenders for the throne: his sons Abdul Rahman and Hussein (by different mothers). The two brothers commanded the support of competing factions of the Riau-Lingga elite. This feud was what eventually led Temenggong Abdul Rahman to leave the court and establish a fiefdom on the banks of the Singapore River. It was this succession dispute that opened a path for Stamford Raffles to further the interests of the British East India Company (EIC) in the region. Since the sultanate was at the time under Dutch influence, Raffles needed a local prince to legitimise his claim over Singapore.

In return for granting the EIC a lease to establish a trading post on Singapore, the British would recognise Hussein as sultan. With this arrangement sealed in the Singapore Treaty of 1819, Singapore came under the tripartite rule of the EIC, the temenggong and “Sultan” Hussein Shah of Johor, while Abdul Rahman ascended the throne in Lingga.12 As the Bugis chronicler Raja Ali Haji lamented, “there were now two kings in one kingdom, with the boundaries determined by two governments, the Dutch and English”.13

After this “one kingdom” ceased to exist with its formal partition by the Dutch and British in the treaty of 1824, Riau-Lingga limped on as a separate kingdom under Abdul Rahman I and his successors.

Spinning Tops and Other Pastimes

Traditional pastimes are still alive and well on Lingga, with programmes to sustain interest actively promoted and undertaken by local authorities. More importantly, the local residents still enjoy them. Take gasing (plural gegasing), for example: Malay spinning tops once popularly played in the villages of Singapore and Malaya. Daik holds gasing tournaments twice a year, and I had the good fortune of witnessing one.

Gasing-spinning requires decent upper body strength, proper form and technical dexterity. Players are split into two teams and the game takes place over several rounds in which teams alternate between spinners and throwers. After spinners cast their gasing, the players from the other team try to knock these gegasing off-balance with their own. The gegasing still standing are then left to spin (adu uri) with the team whose gasing is the last one still spinning winning the round. The roles are then reversed and the rounds repeated. Although the game sounds simple, the precise rules and point-system are incredibly complex.

Gasing-spinning is a very old Malay game and was once considered a sport of princes. Watching the gasing players perform their athletic manoeuvres is electrifying, some having their own signature style and flourish. The gegasing themselves are a marvel, carved out of hardwood with exquisite grain. At their highest speeds, they almost resemble levitating saucers. Still, the most amusing aspect of the experience is hearing the commentator’s enthusiastic live observations. In a different world, one can imagine him commentating at a big-league gasing cup match.

Besides the water sports such as racing kolek and jong (two varieties of sailing canoes), Lingga also holds boat-rowing regattas as well as kite-making and -flying competitions. The sailboats and kites of the present have incorporated more sophisticated and durable materials, though. The people of Lingga appear to have adapted traditional, recreational pursuits according to the needs and conditions of the present, whereas Singaporeans may tend to look down on ours as vestiges of an irrelevant past.

Lingga’s one and only radio station, Radio Bunda Tanah Melayu FM (RBTM; “Malay Motherland Radio”), fills the airwaves with the sound of Malay musical genres. Masters in dondang sayang exchange witty quatrains as a fiddler plays in the background, while on Monday mornings, recitations of pantun and sya’ir (a form of traditional Malay poetry comprising four-line stanzas) keep oral literature alive.

Other leisurely activities are closely intertwined with the realm of the sacred. Every year on the 15th day of the Islamic month of Safar, hundreds still descend on Lingga’s beaches to partake in the ritual of Mandi Safar. This practice has been all but extinguished in Singapore due to changing religious attitudes surrounding some old Malay customs. Mandi Safar (literally “the Bath of Safar”) involves taking a bath in the sea en masse to cleanse oneself of the previous year’s negative energies and to ward off potential misfortune in the coming year.

In Lingga, as was the case in Singapore, this is also an excuse for the young to picnic, socialise and have fun with their friends by the sea. Food stalls are set up as well as makeshift tents and platforms for performances, music and dancing.

At sunset each day, Marcus and I retired to our favourite corner of the island, Tanjong Buton: a long pier lined with food-carts for dining alfresco. Overlooking a charming bay, Tanjong Buton is the perfect setting to savour local delicacies while soaking in the evening sea breeze.

The cuisine of Lingga features rustic Malay dishes, some of which can hardly be found in Singapore today. For example, accompanying the classic asam pedas ikan pari, a spicy stingray stew, is a fried griddle cake of sago flour known as lempeng sagu. Replacing rice as the meal’s staple, lempeng sagu harks back to earlier times in the Malay world when rice was a luxury available only to elites, and the main source of carbohydrates was the humble sago. Indeed, to partake in sago is to taste the natural ecology of Lingga itself – an island of swamps and marshy floodplains – where sago palms proliferate in abundance and sago factories, using age-old extraction methods, still operate on the banks of these palm-lined wetlands.

Mother Island

Riau-Lingga is home to great cultural diversity, even if it is presented as an heir to the courtly Malay traditions of the old Johor Sultanate. Besides the Malays and Bugis, there are the Orang Suku Laut (sea people) who maintain their semi-nomadic lifestyle subsisting on marine products. These communities now maintain a quiet existence on the margins of modernity, but their ancestors once performed an invaluable role in the security and defence of the old sultanate as naval pilots, navigators and combatants.14

Then there are the Chinese, mostly descendants of Teochew settlers. They have been involved in Riau-Lingga society since the 18th century when Daeng Chelak, the Yamtuan Muda of Riau (deputy ruler or viceroy), invited Chinese coolies to establish gambier plantations on Bintan.15 Today, many Teochew residents run sundry shops in towns and villages across the archipelago and support their neighbourhoods by building mosques and other public structures. Some also manage fleets that trawl the surrounding waters, delivering regular supplies of trevally (a species of large marine fish) that end up as fishballs in our soup. On Lingga, there are also coastal towns like Pancur in the northeast with a predominantly Chinese population, while Daik has a prominent Teochew “quarter” with schools, temples and shops built by its longstanding Teochew community.

Carl Trocki has written extensively on how the Bugis-Teochew plantation economy that took shape in Riau was instrumental to the wealth (and labour surplus) achieved by early colonial Singapore.16 Indeed, the success of Riau as a regional port was due in no small part to the symbiotic relationship between the Teochew gambier and pepper planters, and the Malayo-Bugis traders whose networks enabled their distribution and sale. After Riau’s decline in the late 18th century, Bugis traders and Teochew planters moved their base to Singapore. Without the ability to tap into these local networks of economic cooperation and migration, Trocki writes, it was unlikely for Singapore to have had enough port turnover to sustain its operations, at least in its fledgling years. Taking over the functions of old Riau, Singapore became its successor.17

To visit Riau-Lingga, therefore, is to visit an important part of Singapore’s own evolution as a port and society rooted in the Malay world’s patterns of culture and commerce. Even after Singapore and Riau-Lingga were separated, the two islands preserved firm links: well into the 1920s, the princes of Riau-Lingga maintained residences and trading houses in Singapore town.18 Ordinary folk born in Singapore moved to Lingga, and vice-versa, as a matter of routine. Until the 1980s, Singaporean Malays living on the Southern Islands still crossed regularly into Riau to visit their cousins and relatives.

We often lament how “small” Singapore is. Unlike other countries, we do not have a vast countryside that maintains a sense of our “authentic” past or traces of our culture against the continuous flux that characterises life in a global city. In reality, nearby places like Lingga display familiar landscapes and recognisable traditions. Modes of life there remind us of our profound historical ties to this region, and that if we cease to regard Singapore’s identity as being confined to its present-day borders, it can hardly be considered “small” at all. Lingga is a keeper of our pasts, a fount of stories that we in Singapore have long forgotten.

Faris Joraimi is a Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow with the National Library. As a writer and researcher specialising in the history of the Malay World, he has authored various essays for print and electronic media. He is also co-editor of Raffles Renounced: Towards a Merdeka History (2021), a volume of essays on

Singapore’s decolonial history. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in History from Yale-NUS College.

Faris Joraimi is a Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow with the National Library. As a writer and researcher specialising in the history of the Malay World, he has authored various essays for print and electronic media. He is also co-editor of Raffles Renounced: Towards a Merdeka History (2021), a volume of essays on

Singapore’s decolonial history. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in History from Yale-NUS College.NOTES

-

Mark R. Frost and Yu-Mei Balasingamchow, Singapore: A Biography (Singapore: Editions Didier-Millet, 2009), 75. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.57 FRO-[HIS]) ↩

-

Leonard Y. Andaya, “Johor-Riau Empire,” in Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia from Angkor Wat to East Timor, ed. Ooi Keat Gin (Santa Barbara: U.C. Santa Barbara Press, 2004), 699. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING q959.003 SOU) ↩

-

Leonard Y. Andaya, The Kingdom of Johor 1641–1728: Economic and Political Developments (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1975), 312. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RCLOS 959.51 AND-[GH]) ↩

-

Carl A. Trocki, Prince of Pirates: The Temenggongs and the Development of Johor and Singapore: 1784–1885 (Singapore: NUS Press, 1979), 46. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.5142 TRO) ↩

-

The pre-eminence of Riau (Tanjong Pinang in Bintan) as a regional economic hub was so entrenched in the mid- to late 19th century that Joseph Balestier was initially sent to this region to serve as the American consul to Riau. Upon his arrival in 1834, Balestier discovered, to his shock, that Riau had long declined to a backwater and hence amended his posting to become America’s first consul to Singapore. See Richard E. Hale, The Balestiers: The First American Residents of Singapore (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish, 2016), 6–13. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.57030922 HAL-[HIS]); Imran Bin Tajudeen, “From Riau to Singapore, 1700s–1870s: Trade Posts and Urban Histories – a Response to the Book Singapore: A 700-year History,” in Singapore Dreaming: Managing Utopia, ed. H. Koon Wee and Jeremy Chia (Singapore: Asian Urban Lab, 2016). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 303.495957 SIN) ↩

-

Like all canonical pantun (a Malay oral poetic form), this one was passed down through the generations without a known author. However, it has been recorded in some published compilations. For example, see Arthur Wedderburn Hamilton, Malay Pantuns = Pantun Melayu (Singapore: Donald Moore, 1956), 77. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RCLOS 899.281 MAL-[JSB]). Translation by author. ↩

-

John N. Miksic, “Three Mountains in Malay History,” in Zai Kuning, Dapunta Hyang: Transmission of Knowledge, accessed 20 August 2021, https://dapuntahyang2018.wordpress.com/three-mountains-in-malay-history. ↩

-

Aswandi Syahri, “Negeri dan Istana Baru Sultan Mahmud Muzafarsyah Daik Lingga (1849),” Jantung Melayu.com, accessed 20 August 2021, https://jantungmelayu.com/2019/10/negeri-dan-istana-baru-sultan-mahmud-muzafarsyah-daik-lingga-1849/. ↩

-

Sri Sugiharta, Masjid-Masjid Kuno di Sumatra Barat, Riau dan Kepulauan Riau (Batusangkar: Balai Pelestarian Peninggalan Purbakala Batusangkar, 2006), 57. (Not available in NLB’s holdings) ↩

-

Imran Bin Tajudeen, “Adaptation and Accentuation: Type Transformation in Vernacular Nusantarian Mosque Design and Their Contemporary Signification in Melaka, Minangkabau and Singapore,” ISVS IV: Pace or Speed?, 4th International Seminar on Vernacular Settlement, Ahmedabad, India, February 14–17, 2008: Proceedings (Ahmedabad: Print Vision for CEPT University, 2008), 136, Academia, https://www.academia.edu/300404/Imran_bin_Tajudeen_2008_Adaptation_and_Accentuation_Type_transformation_in_vernacular_Nusantarian_mosque_design_and_their_contemporary_signification_in_Melaka_Minangkabau_and_Singapore. ↩

-

See Farish Noor and Eddin Koo, Spirit of Wood: The Art of Malay Woodcarving (Hong Kong: Periplus, 2003). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RART q736.409595 NOO) ↩

-

C.H. Wake, “Raffles and the Rajas: The Founding of Singapore in Malayan and British Colonial History,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 48, no. 1 (227) (1975): 60. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Raja Ali Haji ibn Ahmad, The Precious Gift (Tuhfat al-Nafis), trans. Virginia Matheson and Barbara Andaya (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1982), 244–45. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.5142 ALI) ↩

-

Timothy P. Barnard, “Celates, Rayat-Laut, Pirates: The Orang Laut and Their Decline in History,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 80, no.2 (293) (December 2007): 35. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Gambier was a valuable crop used in tanning leather and its trade contributed to the wealth of Riau-Lingga. The Teochew planters who arrived in Singapore from Riau introduced the kangchu cultivation system that dominated the interior for much of the early 19th century. See Carl Trocki, Prince of Pirates: The Temenggongs and the Development of Johor and Singapore 1784–1885 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2007), 33–35. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.5103 TRO). For information about gambier plantations in early Singapore, see Timothy Pwee, “From Gambier to Pepper: Plantation Agriculture in Singapore,” BiblioAsia 17, no. 1 (Apr–Jun 2021). ↩

-

Trocki, Prince of Pirates, 34. ↩

-

Carl Trocki, Singapore: Wealth, Power and the Culture of Control (New York: Routledge, 2006), 8. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.5705 TRO-[HIS]). On Singapore’s early Teochew community, see Jason Heng, “An Old Teochew Oral Account Sheds New Light on the 1819 Founding of Singapore,” in Singapore. National Library Board, Chapters on Asia: Selected Papers from the Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship (2014–2016) (Singapore: National Library Board, 2018), 291–331. (From BookSG, Call no. RSING 959.57 CHA-[HIS]) ↩

-

Barbara Andaya, “From Rum to Tokyo: The Search for Anti-Colonial Allies by the Rulers of Riau, 1899–1914,” Indonesia, no. 24 (October 1977): 128. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩