Cold War Rivalries Fuel Propaganda Battle in Singapore in the 1940s and 1950s

In the post-World War II period, Singapore was a battleground for ideological competition between the Soviet Union and China on one side, and the United States and United Kingdom on the other.

By Chow Chia Yung

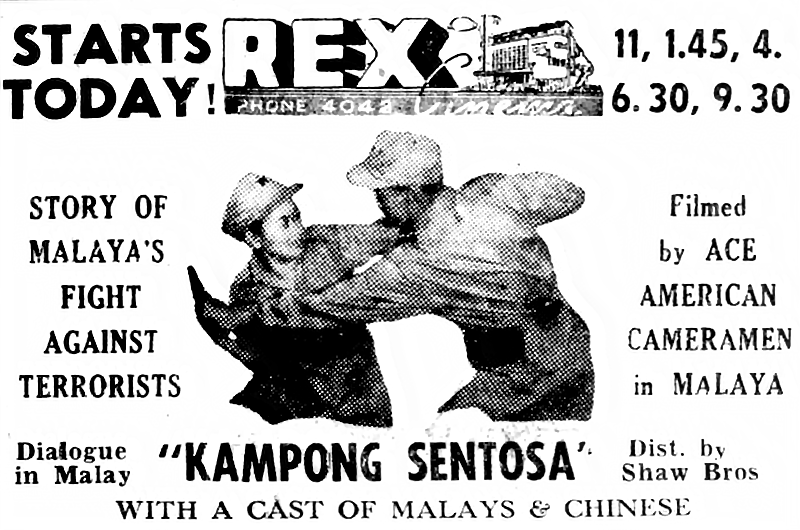

On 10 May 1953, the Straits Times ran a story about a film titled Kampong Sentosa,1 which had premiered in Singapore at the Rex Theatre. In Malay with an all-local cast, the film tells the story of a village in Malaya which was being terrorised by bandits in the surrounding jungle during the Malayan Emergency (1948–60). The story has “love interest and enough suspense to draw Malay-speaking audiences”.2

This, however, was no ordinary film. Declassified archival materials reveal that Kampong Sentosa was actually secretly funded by the State Department in Washington DC.3 This was part of a global Cold War effort led by the United States (US) to roll back against the spread of communism.

In the post-World War II era, the world was riven by great superpower rivalry, with the US and its allies on one side, and the Soviet Union and its allies on the other. Apart from the nuclear standoff, the conflict was also an ideological one with both sides attempting to win the battle for hearts and minds.

Soviet Cultural Offensive

“Soviet social system has proved to be a more viable and stable than the non-Soviet social system, that the Soviet social system is a better form of organisation of society than any non-Soviet social system.”4

Film is a very powerful medium, and some of the earliest efforts by the Soviet Union relied on the power of film. In 1947, Director of Malayan Security Service John D. Dalley informed the Colonial Secretary in Singapore “that there is a campaign in Singapore to spread Soviet propaganda through films and periodicals”. In that year, two Soviet documentaries, May 1st Celebrations and Festival of Youth, were screened at the Jubilee Theatre in Singapore.5

The Morning Tribune reported that the documentary on the Soviet Union’s 1946 May Day celebrations in Moscow had highlights that included a gigantic military parade which was reviewed by Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin. The other film, Festival of Youth, focused on the “vitality and talent of the youths of Soviet Russia who participated in an all-day sports parade…” Both films were in technicolour, noted the newspaper. It added that they “compare very favourably with those from Hollywood in technique and production” and “should serve as an ‘eye-opener’ for those of us who know so little, except from book and news extracts, about a country which is branded as ‘Red’”.6

May 1st Celebrations was in Mandarin, while English commentary was provided for Festival of Youth. These two films attracted huge Chinese audiences. Jubilee Theatre also issued concession tickets for the viewing of these two Soviet films to schools and associations.7

In addition to films, the Soviet Union also relied on print materials. According to an American State Department report, the Soviet Union produced approximately 25 to 30 million books in various languages in the 1950s and most of them contained Marxist-Leninist titles or themes. Some of these works found their way to Singapore. They include titles such as Study the Philosophy of Marxism and Leninism and A History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.8 Both books were translated into Chinese.

The Soviet authorities also sent propaganda items to Russians living in Singapore to convince them to return to their home country. In 1956, the Singapore Standard noted that Singapore was being flooded by “Russian booklets, weeklies and pamphlets depicting a ‘new way of life’ in the Soviet Union”.9

China’s Revolutionary Literature

“Proletarian literature and art are part of the whole proletarian revolutionary cause…”10

After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Chairman Mao Zedong pledged to support global communist revolutionary movements. It would take a while but the effort would eventually take off. In 1959, a sessional paper from the Legislative Assembly of Singapore noted that “certain publishing houses – the majority of which are in mainland China – are consistently exporting to Singapore books, both ancient and modern, literary and scientific, which are tainted with Communist ideology”.11

One example cited was a Chinese-English dictionary, 通俗小字典 (Popular Small Dictionary), published by the Tung Fang Book Co. in Shanghai. In it, the entry “敬爱”, which means “respect and love”, has this example given: “Everyone respects and loves Chairman Mao.”12

The dictionary’s definition for the Chinese Communist Party (“共產黨”) was the “[V]anguard of the Proletarian rebellion. It is the political party of the workers class”. It went on to define communism as the “realisation of a Communist society wherein there is no fleecing of some persons by some other persons. In this kind of society, everybody does the job he can do best, get what he needs, and leads the most reasonable and most happy life”.13

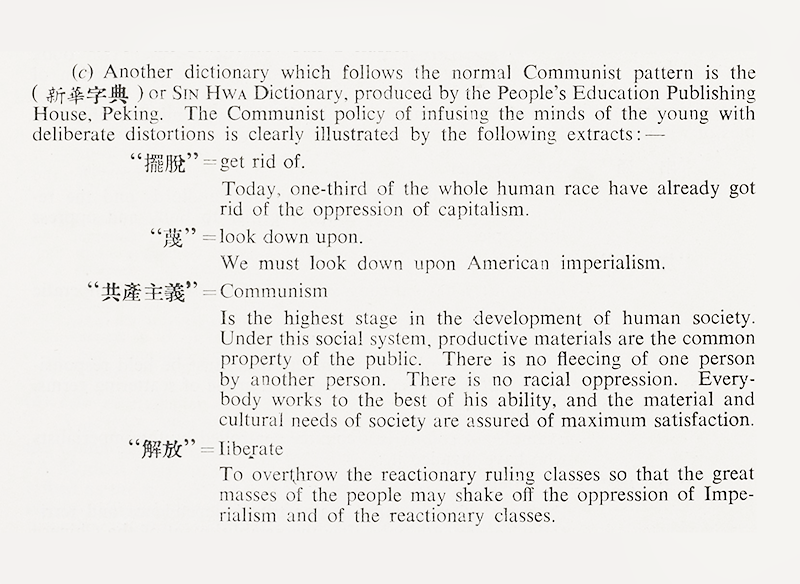

Another Chinese-English dictionary highlighted was 新華字典 (Sin Hwa Dictionary), which was published by the People’s Education Publishing House in Peking (now Beijing). It defined the characters “擺脫” to mean “get rid of” and gave the example: “Today, one third of the whole human race have already got rid of the oppression of capitalism.” The character “蔑” was translated to mean “look down upon” and the example given was: “We must look down upon American imperialism.” “共產主義”, which means “Communism”, was defined as “the highest stage in the development of human society”.14

Dictionaries were not the only focus. The book, Singing and Acting for Young Children Vol IV, had songs with lyrics that glorified the success of communism in China such as “The entire China wants liberation” and “Equality and freedom in New China”.15

China also produced literature in support of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) during the Malayan Emergency period. The educational book in English, simply titled Malaya, sought to get readers to sympathise with the MCP and to support their efforts. The book noted that the party had to go underground in 1948 because “of the persecution of the British imperialists. Following this it initiated and led armed resistance against the British in the struggle for national liberation… the MCP has been carrying on its struggle against enslavement and colonial rule”.16

A significant quantity of communist materials published in China made its way into Chinese bookshops in Singapore before the British colonial government began to impose strict controls starting from September 1950. It was not completely successful though, and a spokesman of the Chinese Secretariat in Singapore commented in 1951 that “now and then a Communist book might slip through our net”.17

British Anti-communist Efforts

“We should adopt a new line in our foreign policy publicity designed to oppose the inroads of Communism by taking the offensive against it… and to give a lead to our friends abroad and help them in the anti-Communist struggle… to provide material for our anti-Communist publicity through our Missions and Information Services abroad. The fullest co-operation of the BBC Overseas Services would be desirable.”18

In response to the communist propaganda in Singapore, the British initiated a series of counter-measures. Besides banning the imports of communist films and literature, the government established the Anti-Communist Bureau to “stimulate active democratic sentiment and to endeavour to win over Communists and fellow travellers”.19 This bureau oversaw and implemented activities to counter the flow of communist propaganda.

In late 1949, some 200 pamphlets were distributed across Singapore to warn people against communism and make them enthusiastic about democracy.20 An anti-communist pamphlet, The young man who couldn’t take any more, was produced in English and Chinese, and thousands were printed with the intention of being distributed in schools by 1950. This pamphlet provided “a plain account of what happens to students in Communist countries, who wish to preserve their freedom to think”.21 It was also designed to portray communism in a negative light.

Radio broadcasts by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) were another tool used by the colonial government. BBC emerged from World War II with a greatly expanded audience and a reputation for objectivity and truth-telling. That reputation made its news credible and gave Britain a major propaganda advantage.22 The BBC’s credibility was crucial in serving Britain’s anti-communist publicity objectives.

The BBC accepted an invitation from the United Kingdom government to establish its radio broadcasting service in Singapore and it ended up taking over the British Far Eastern Broadcasting Service. The BBC began its radio operations in Singapore in 1948 with its office and studio on Caldecott Hill. Singapore residents could tune in to local radio programmes directed by BBC personnel as well as news from London. In addition to English, the BBC radio station in Singapore also aired daily radio programmes in Mandarin and Cantonese.23 This was part of the BBC’s strategy to reach out to the predominantly Chinese population in Singapore.

The BBC radio station in Singapore was also used by Britain as a regional radio base to broadcast anti-communist information across Asia. As the Straits Times noted in 1949: “It was the intention to build a new station which was to become the Voice of Britain in Asia, radiating programmes to the entire Far East — from Japan to India… Obviously the campaign against Communism in Asia must be fought in Asia… If the radio weapon is to be of real use to Britain, and to Malaya, then the main broadcasts must have their origin in Singapore…”24

The United States Information Service

“We must make ourselves known as we really are – not as Communist propaganda pictures us. … We must make ourselves heard round the world in a great campaign of truth.”25

Just as the British had the BBC, the US relied on the United States Information Service (USIS). This was a state agency that served the political interests of the American government, which included assisting in “the offensive campaign of truth against Communist propaganda”.26 To this end, the USIS launched a series of overseas information programmes under its cultural diplomacy initiative.27

The Singapore branch of the USIS Library was officially opened on 2 May 1950 in Raffles Place. Its collection – consisting primarily of American books, newspapers and magazines – exposed the people in Singapore to American values and worldviews.28

Books such as Animal Farm by George Orwell and Rice-Sprout Song by Eileen Chang made their appearances on the library’s bookshelves.29 These two titles were known for their anti-communist themes. The USIS Library’s collection was curated in a way that would sell American ideals to the people here, which was essential in undermining the appeal of communism.

The USIS Library welcomed the public to browse or borrow its reading materials regardless of membership. There was a constant stream of patrons visiting the library, which welcomed its 10,000th member within a few months of its opening.30

The USIS also funded the production of anti-communist films in Singapore such as Kampong Sentosa. The agency provided covert financial support for the production of this film, which was helmed by Hollywood director B. Reeves Eason.31

Besides Kampong Sentosa, the USIS also developed its own documentaries for public viewing at the USIS Library. The documentaries portrayed the domestic and international policies of the US in a favourable light. The collection of the library also included anti-communist documentaries such as In Defense of Peace and the Hungarian Story.

In Defense of Peace documented measures by the Soviet Union to obstruct the efforts of the United Nations to maintain world peace in the aftermath of World War II, while Hungarian Story showcased Hungarian citizens staging a revolt against the oppressive Hungarian communist regime.32 The distribution of these USIS films to Singapore was intended to persuade the people to be wary of communism and to cultivate the perception that communism was a threat to peace and stability, both domestically and internationally.

Immense and Intense

The Cold War period was a major period of geopolitical tension that played out in various spheres: military, economic, political and culture. Given that both the US and the Soviet Union were superpowers, it is fortunate that they never escalated into a nuclear war, though the world certainly came close with events such as the Cuban Missile Crisis.33

While hard power – measured by the size of armies and nuclear arsenals – was important, soft power was just as crucial. The propaganda battle was an integral component of the Cold War as both blocs vied for influence. They leveraged print, radio and films to promote their own point of view and undermine those of their ideological opponents. This battle played out throughout the world, and Singapore was very much part of the battleground.

Chow Chia Yung is an Assistant Archivist with the National Archives of Singapore. He provides archival-related reference services for researchers.

Chow Chia Yung is an Assistant Archivist with the National Archives of Singapore. He provides archival-related reference services for researchers.NOTES

-

Kampong Sentosa can be viewed at the National Archives and Records Administration in the United States. See https://catalog.archives.gov/id/52534. ↩

-

Nan Hall, “What Lies Behind Mystery of ‘Kampong Sentosa’?” Straits Times, 10 May 1953, 11; “Emergency on the Screen,” Straits Times, 8 May 1953, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Hee Wai-Siam , Remapping the Sinophone: The Cultural Production of Chinese-language Cinema in Singapore and Malaya Before and During the Cold War (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2019), 116. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 791.4308995105951 XU) ↩

-

Joseph Stalin, “Speech Delivered by Stalin at a Meeting of Voters of the Stalin Electoral District, Moscow,” 9 February 1946, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Gospolitizdat, Moscow, https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/116179. ↩

-

“Soviet Propaganda (Films),” Director of Malayan Security Service to the Colonial Secretary, Singapore, in the National Archives (United Kingdom), Singapore: Soviet Activities in South East Asia, Including Films. Secret – Migrated Archives, 1 October 1947, 1. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. FCO 141/14370); “Russian Films In Singapore,” Morning Tribune, 1 November 1947, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Director of Malayan Security Service to the Colonial Secretary, Singapore”; “Russian Films Popular,” Straits Times, 12 November 1947, 3. (From NewspaperSG); “Soviet Film Propaganda,” Malayan Security Service Political Intelligence Journal no. 19 (15 November 1947): 1, in the National Archives (United Kingdom), Singapore: Soviet Activities in South East Asia, Including Films. Secret – Migrated Archives. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. FCO 141/14370) ↩

-

Greg Barnhisel, “Cold Warriors of the Book: American Book Programs in the 1950s.” Book History 13 (2010): 192. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); “Police Seize Red Press,” Straits Budget, 25 June 1958, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“‘Come Back To Moscow’ Plea to S’pore White Russians,” Singapore Standard, 8 August 1956, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

John Burns, “Latest Chinese Art Is Following Mao’s Line,” New York Times, 18 July 1972, 25, https://www.nytimes.com/1972/07/18/archives/latest-chinese-art-is-following-maos-line.html. ↩

-

“Legislative Assembly, Singapore, Sessional Paper No. Cmd 14 of 1959,” in the National Archives (United Kingdom), Singapore: Control of Cultural Influences from the Chinese Mainland. Secret – Migrated Archives, 9 March 1952, 2. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. FCO 141/15152) ↩

-

“Legislative Assembly, Singapore, Sessional Paper No. Cmd 14 of 1959,” 6. ↩

-

“Legislative Assembly, Singapore, Sessional Paper No. Cmd 14 of 1959,” 5–6. ↩

-

“Legislative Assembly, Singapore, Sessional Paper No. Cmd 14 of 1959,” 5–6. ↩

-

“Legislative Assembly, Singapore, Sessional Paper No. Cmd 14 of 1959,” 8. ↩

-

“Legislative Assembly, Singapore, Sessional Paper No. Cmd 14 of 1959,” 6–7. ↩

-

“Fewer Red China Book Available,” Straits Times, 3 October 1951, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Future Foreign Publicity Policy”, 4 January 1948, CP (48) 8, CAB 129/23, Cabinet Papers, Public Record Office in London, in the National Archives (United Kingdom), http://filestore.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pdfs/large/cab-129-23.pdf. ↩

-

A.W. Frisby, “Objectives and Methods of the Anti-Communist Bureau Set Up By the Director of Education at the Request of the Colonial Secretary,” in the National Archives (United Kingdom), Singapore. Counter-Communist Education. Secret – Migrated Archives, 13 October 1949, 1. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. FCO 141/14400) ↩

-

“Report On Counter Communist Education Bureau to 31 December 1949,” in the National Archives (United Kingdom), Singapore. Counter-Communist Education. Secret – Migrated Archives, 11 December 1949, 1. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. FCO 141/14400) ↩

-

“Anti-Communist Bureau,” in the National Archives (United Kingdom), Singapore. Counter-Communist Education. Secret – Migrated Archives, 31 January 1950, 1. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. FCO 141/14400) ↩

-

John Jenks, British Propaganda and News Media in the Cold War (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006), 21, 91. (From ProQuest Ebook Central via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

“BBC to Control S’pore Station,” Straits Budget, 12 June 1947, 16; “Two Radio Stations,” Straits Times, 29 August 1949, 4; “BBC Having a Contest This Month,” Singapore Free Press, 5 December 1950, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Nicholas J. Cull, The Cold War and the United States Information Agency: American Propaganda and Public Diplomacy, 1945–1989 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 55. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R327.11 CUL) ↩

-

“Letter Sent from Office of the Commissioner General for the United Kingdom in Southeast Asia to J.C. Barry, ESQ., who is Deputy Secretary for Defense and Internal Security in Colonial Secretary’s Office in Singapore,” in the National Archives (United Kingdom), Singapore. United States Information Services (USIS) activities in Singapore and the Federation of Malaya, Proposal for a field study in Malaya by the Bureau of Applied Social Research of Columbia University. Secret – Migrated Archives, 8 August 1951. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. FCO 141/14533) ↩

-

Pamela Spence Richards, “Cold War Librarianship: Soviet and American Library Activities in Support of National Foreign Policy, 1946–1991.” Libraries & Culture 36, no. 1 (Winter 2001): 193. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

“For Those Who Love Reading,” Indian Daily Mail, 24 April 1950, 4; “Singapore’s First Free Library,” Malaya Tribune, 29 April 1950, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Books In Malay Now at USIS Library,” Singapore Free Press, 11 August 1960, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“USIS Library’s 10,000th Member,” Indian Daily Mail, 19 July 1950, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Hee, Remapping the Sinophone, 114, 116. ↩

-

United States Information Service (Singapore). Audio-visual Section, Catalog of 16mm Motion Picture Films (Singapore: U.S. Information Service, Audio-Visual Section, [n.d.]), 47. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 016.79143 UNI) ↩

-

The US and the Soviet Union engaged in a tense, 13-day political and military standoff in October 1962 over the installation of nuclear-armed Soviet missiles on Cuba, just 90 miles (145 km) from American shores. Disaster was averted when the Soviet Union offered to remove the missiles provided that the US promised not to invade Cuba. ↩