Johor at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair

The story of how Johor ended up at the Chicago World’s Fair is an unexpected twist in Malaya’s colonial past.

By Faris Joraimi

My favourite boyhood novel was Jules Verne’s classic, Around the World in 80 Days, which captured the scientific wonder of the late-19th century. European conquest of much of the world opened it up to travel by steam and rail, but many Asians were also active participants in that age of acceleration. The growth of the annual Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca, enabled by steamship services, made Singapore a global hub in a modern Islamic network.

Intellectuals from Cairo to Tokyo urged their societies to join the West in a future limited only by the bounds of Man’s genius and imagination. (Often literally men’s, as women’s contributions were frequently overlooked.) That ideal was elaborately dramatised in the world’s fairs: spectacles showcasing the latest inventions and gathering humanity’s shared intellectual and artistic advances in one place.

These world’s fairs had theatrical scale and encyclopaedic scope. The 1851 Great Exhibition in London – or more marvellously in full, the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations – counted the flushing toilet among its premieres. Electricity and engineering enthralled visitors to the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris, where they were introduced to phonographs, telephones and the Eiffel Tower.

One of the most impressive world’s fairs was the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, which featured a little Southeast Asian state that few in the West had heard of: Johor. Encountering this story through fragmentary blog posts and cursory mentions in academic studies, I decided to dig deeper. How did Johor – which Singaporeans today know little about besides being a place for cheap fuel and groceries – end up on this international stage when few other Asian states did? As it turns out, the obscure episode embodied the contradictions of the late 19th century, its dream of progress built on nightmarish exploitation. It exemplified minor players using colonial media like the world’s fairs to manoeuvre and survive as the threat of European conquest closed in.

Dramatis Personae

During the 19th century, Johor was transformed from a traditional Malay polity into a modern state by Abu Bakar (1833–95), the sultan and a dynamic reformer. His grandfather, Temenggung Abdul Rahman, was the Malay lord who facilitated Stamford Raffles’ fateful meeting with Tengku Hussein in 1819, leading to the establishment of a trading post in Singapore.

Inheriting the large territory of Johor in 1862, Abu Bakar expanded its Teochew plantation economy and created a bureaucratic government to manage its revenues. He modelled the capital Johor Bahru after European cities and adopted English tastes and habits. A friend of Queen Victoria and regular visitor to European capitals, Abu Bakar cultivated the image of an enlightened Eastern ruler.

The sultan was among the prominent non-European leaders of the time who travelled to form strategic international connections and gain prestige; others included King Kalakaua of Hawai‘i and King Chulalongkorn of Siam (now Thailand). Their tours sought to prove that the land they held sway over were – contrary to European beliefs – cultured and progressive, and therefore fit to govern themselves.

So effective was Abu Bakar’s “advertisement” of his administration that it only accepted British suzerainty in 1914. Before that, Johor enjoyed membership in the family of “civilised” nations. By 1893, Johor had fixed its borders, gained British recognition of its independence, and was about to implement its own constitution.1 Joining a world’s fair affirmed its stature.

Enter Rounsevelle Wildman (1864–1901), an American reporter-turned-diplomat. His first appointment was as United States (US) Consul-General to Singapore, starting in 1890.2 In his account Tales of the Malayan Coast (1899),3 Wildman conjured up the picturesque Malaya as Western officials saw it: a timeless landscape with inhabitants cast in specific roles. Sultan Abu Bakar, at least, impressed him. At a palace banquet Wildman attended in Johor Bahru, the sultan served an international menu and chided Westerners with wit and humour for thinking Malays were savages.4

Wildman and Abu Bakar’s relationship must have been cordial; the latter even lent Wildman his personal yacht for sailing trips around Singapore and the Melaka Strait, playing Robinson Crusoe.5 No surprise then that when Wildman suggested to Abu Bakar that Johor participate in the Chicago World’s Fair, the latter placed his trust in the American.

Both men had something to gain. In preparing for the fair, the US tasked its overseas consuls to persuade their host countries to join. The Singapore government wanted nothing to do with it, a decision that the Straits Times criticised, saying that “the Colony does not understand the value of judicious advertising”, especially since the US was the city’s largest importer after England.6 Wildman thus turned to Johor to show that he was fulfilling his responsibility to contribute to the fair. Johor, an emerging market for mining and agriculture, saw the economic value of its presence in Chicago.

By July 1892, a year before the fair, the Singapore press confirmed Abu Bakar’s pledge to send an exhibit to Chicago, consisting of a model kampong, actual Malay men and women at work, cultural artefacts and commercial products.7 The sultan himself would also travel to Chicago.

News of the impending visit soon crossed the Pacific, and American newspapers printed colourful introductions about Abu Bakar and Johor, its size and population. One described him as “one of the most intelligent of the Eastern sovereigns”.8 But as the talents of an “Oriental” could only be attributed to European guidance, another called him “a good representative of what a Malay of superior caste and education can be when gifted with the opportunities of civilized life”.9

Arriving in New York in January 1893, Wildman continued building public anticipation for “the only independent Malay kingdom”.10 Plans for the exhibit and Abu Bakar’s tour had grown more ambitious. He would visit Washington with an entourage of Malay princes and a troupe of dancing girls, staying for four months. The exhibit would boast a village of 100 Johoreans making sarongs, and even include tigers from the sultan’s private collection.11

A pair of commissioners were appointed to oversee the Johor exhibit in Chicago: Harry Lake, an English engineer who was also Abu Bakar’s secretary, as well as Abdul Rahman Andak, one of Johor’s most influential statesmen.12 Confident, eloquent in English and a shrewd negotiator, Abdul Rahman was not popular with Singapore’s British governors, who were uncomfortable with Johor’s autonomy. He was just the man for this intricate mission.

From Johor to Chicago

In late February 1893, Abu Bakar and his entourage comprising 30 “native princes”, Abdul Rahman and Harry Lake steamed out of Singapore, headed for Europe.13 Abu Bakar would sojourn in the German spa-town of Carlsbad (Karlovy Vary in the Czech Republic today) to nurse his declining health. The plan was to visit the US and join Wildman in June. Abdul Rahman and Lake continued across the Atlantic and reached New York in April, accompanied by six Malay artisans who would build the kampong at the exhibit. Later, the two men went to Washington to meet the secretary of state and US president Grover Cleveland.14

The American press was busy milling tall tales about Abu Bakar as an extravagant Asiatic despot. Plenty were perpetuated by Wildman himself, who had become Johor’s spokesman. He painted for American readers a fantastic Johor worth “$10,000,000 diamonds” and other luxuries in the New York magazine, Harper’s Weekly.15 This line was repeated by newspapers across the country.16

One letter to the Singapore Free Press mocked the depictions as “bunkum”,17 and Abu Bakar was so annoyed by the “ridiculous” statements that he threatened to cancel his visit to the US.18 The Singapore newspapers pulled no punches. The New York Herald may be a top US paper, “but its geographical knowledge is slender”, noted the Free Press.19 Clearly, the US’ knowledge of the world had not caught up with its status as a rising power in the Pacific.

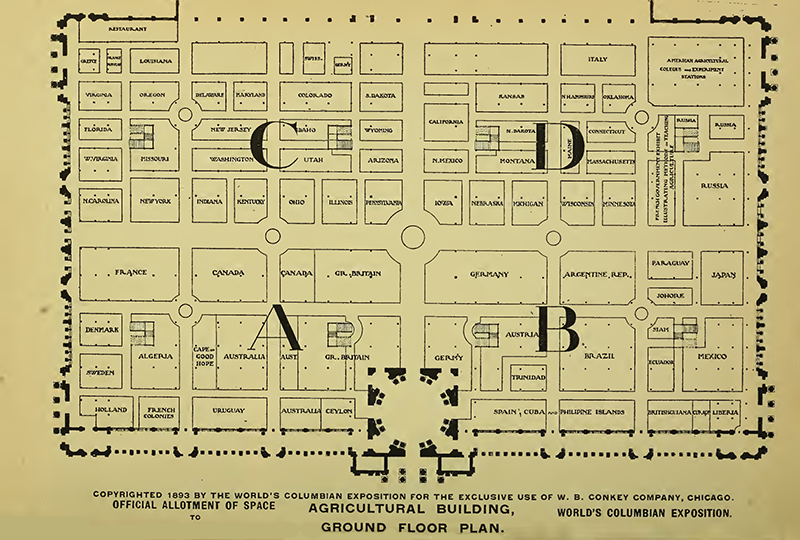

Meanwhile, on the shores of Lake Michigan, thousands of workers toiled to raise the monumental campus of the Chicago World’s Fair. A railroad terminus connected visitors from the city’s Grand Central Station to Jackson Park, the fair’s bustling core. Leaving the station, a visitor was struck by the gleaming neoclassical facades of the “White City” where the Administration Building, Agricultural Building and Manufactures Building surrounded a vast pool.

A network of canals connected the pool to lagoons and ponds in the north, where imposing structures housed exhibits dedicated to horticulture, women, the fine arts, and others. It was a city within a city. Designed by leading American architects, the fair proclaimed the US as an heir to the glories of Europe. Among the national pavilions surrounding the North Pond were the only Asian countries represented: Siam and Japan. But where was Johor?

An official catalogue of the fair lists Johor under “No. 12, Oceanic Trading Company” located in “Midway Plaisance”, a long field just outside the main exhibition.20 Johor shared the exhibit space jointly with Samoa, Fiji and Hawai‘i. On the souvenir map, No. 12 is mislabelled as “Dutch Settlement”.21

Johor’s village included a main bungalow and attap-roofed booths selling Johor-grown tea, pineapple juice (“the national drink”) plus Malay and Chinese trinkets.22 About 25 Malay women and men at a time managed the exhibit. In the bungalow was a royal bed, an eating throne and a loom for weaving sarongs, alongside a collection of krises, agricultural tools, game objects, timekeeping devices and coins, Chinese “curios”, Johor woods, animal hides, and stuffed birds. There were also photographs of Johor landscapes specially produced by the famous Singapore studio, G.R. Lambert & Co.23

Newspapers also mentioned a “permanent exhibit” in the Agricultural Building which was not part of the original plan. That exhibit was dedicated to Johor’s tea culture, then centred on an 800-acre estate by the Skudai River growing the Assam hybrid.24 Planting had begun in 1882 and Johor was trying to promote tea as the next big cash-crop after demand for its chief exports, gambier and pepper, had declined.

On 1 May 1893, the fair opened in a formal ceremony. Abdul Rahman represented Johor, “a noticeable figure, dressed in black with a purple apron tied about him, and with an Oriental wealth of insignia across his broad expanse of shirt front”.25 The man was undoubtedly in Malay dress, the “apron” being his samping (hip-wrapper). All the fanfare, though, belied the twists and turns of an underhanded scheme by Rounsevelle Wildman to take advantage of the ambitious Johoreans.

Rounsevelle Wildman’s Scheme

In a report that appeared months later, the Singapore Free Press accused Wildman of exploiting Johor for his own advantage. According to this story, Wildman had begged Abu Bakar to contribute an exhibit at the fair, tempting him with the “glory” it would bring. With his “Western genius”, Wildman made Abu Bakar sign an unfair contract.26

The terms entailed Johor providing Wildman with materials to build the village on Midway Plaisance and reimbursing him for all expenses incurred for arranging for Johor’s exhibit there. The American consul sweetened the prospects for Abu Bakar by presenting Midway Plaisance as the main stage where “all foreign nations will exhibit”.27

Conveniently, Wildman was transferred from his Singapore post to Germany soon after the agreement was sealed. The story fast forwards to Harry Lake and Abdul Rahman Andak’s arrival in Chicago, expecting a spot in the main show like other independent nations and ready to pay the exhibitor’s fee that Wildman’s contract had stipulated. A fair official told the Johor party that no fee was required, and that Midway Plaisance was “the showman’s quarter and not the main part of the Fair”.28 The American consul had wheedled Johor into paying to join what was in reality an amusement park.

More than carnival rides, however, Midway Plaisance – George Ferris’ original “Ferris Wheel” first debuted there – was also an ethnographic gallery, with exhibits such as a “Cairo Street” and “Turkish Village”. The Midway was intended to display humanity’s supposed order of civilisation, from the most advanced (European) societies at one end to the lowest (Africans and Pacific Islanders) at the other.

Such ethnographic galleries, which made their debut at the Paris Exposition in 1889, were typical of the world’s fairs. Together with the museum, zoo, or botanical garden, they shared the colonising function of collecting and bringing back objects from distant environments for observation and education. Colonial empires vied to display and debase their captive colonies.29 “Natives” were shipped over far from their homes, dressed in traditional attire to perform “occupations” for the amusement of onlookers. Away from their accustomed climate, many died.30

Like other Americans, Julian Hawthorne (son of the famous novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne) found Midway Plaisance the most entertaining section of the Chicago fair, calling it “The World as Plaything”.31 A playable world, a world without consequences, where people were reduced to toys without agency and sorted into boxes labelled “civilised”, “half-civilised” and “savage”: such was the cost of modernity.

Racism saturated Chicago’s “Columbian Exposition”, whose very name commemorated 400 years since Christopher Columbus brought “the torch of civilisation” to the New World, never mind his pivotal role in the violent colonisation of Native American lands. The US intensified this process in what it considered a sacred duty to subdue the “wild” frontier in a divine plan called Manifest Destiny. In that vein, the Chicago World’s Fair displayed Native Americans as a vanishing race.32

The fair’s organisers also excluded Black Americans from the main exhibits and ignored calls for a “Coloured Exhibit” despite African-American contributions to the US (including having built its wealth through their enslaved labour).33 Johor’s leaders, themselves opportunists who made use of the fair as a medium for self-promotion and legitimacy, could not escape the hierarchy and certainly were not considered equals to the Europeans exhibiting in Midway Plaisance.

Without a place in the main section, a furious Abdul Rahman planned to leave the exhibit’s materials with the US government and return home. Then Honduras unexpectedly withdrew from its slot in the Agricultural Building just a few days before the opening.34 With the space available, Johor now had a permanent exhibit all to itself. However, Wildman had transferred rights to the Johor exhibit to the Oceanic Trading Company, whose representatives asked Abdul Rahman to hand over the materials. He defied them and wrote to Wildman demanding an explanation.

Stationed in Germany, Wildman met Abu Bakar and framed Abdul Rahman as negligent, refusing to build the village while living large “in that fast and godless city of Chicago”.35 Wildman asked Abu Bakar to make him Johor’s commissioner instead to sort out matters in Chicago.

The tide turned when Harry Lake travelled to Carlsbad to personally explain matters to Abu Bakar. Wildman, defeated, went to Chicago to negotiate a new agreement between himself, Oceanic Trading and Johor. The Johoreans agreed to give Wildman the exhibit’s unsold surplus, while he paid to build the village at Midway Plaisance. He also agreed to give a portion of the proceeds to the fair, the company and Johor.

“If there is a moral attached,” the Singapore Free Press reported, “it is that the business methods of the West are not always appreciated by the people of the East, and that when a Westerner tries to get the better of the simple and slothful Oriental he does not always come out ahead”.36 The further truth of the matter is that the “Orientals” had been neither simple nor slothful.

History from the Margins

As the Chicago World’s Fair drew to a close in October 1893, Johor was congratulated for an exhibit on par with its “more mighty neighbours”.37 Abu Bakar himself never made it to Chicago though.38 He remained in ill health and died of pneumonia two years later in London. Abdul Rahman remained a loyal servant of Johor until British pressure ousted him in 1909. Wildman went on to serve terms in Hong Kong before getting involved in the Philippine-American War as a friend of the Filipino leader and revolutionary Emilio Aguinaldo. Wildman’s eventful career was cut short in 1901 when he and his family went down with their ship off San Francisco.

Chicago remained an achievement for Johor. In Haji Mohamed Said’s chronicle of Abu Bakar’s reign, the writer credited the exhibit for “raising the fame” of Johor in the eyes of the world.39 Johor belonged to a wider story of marginal peoples rising to the challenge of modernity, despite colonial structures of exclusion.

Malayan responses to the American press proved that Asians not only knew but also resisted how Westerners characterised them. To adapt, they may have been complicit in the imperial scheme, but given that the colonial order left them with few viable options, reinventing themselves for a new international system was radical in its own way. Japan, for instance, played the game well by becoming an industrial and military power. Lacking the same capabilities, Johor resorted to diplomacy and trade. Sovereignty was a shifting mirage in the jungle of geopolitics, given substance and legitimacy through rituals of recognition such as the world’s fairs.

Growing up in a society where too often, the discourse around Malays relegates the community to a minimal role in the modern past and present,40 I was thrilled to find a Malay state demanding a place on the stage of history, to have a share in its making. It is in retrieving and rewriting such stories back into wider consciousness that we truly appreciate history as a grand movement of the small and forgotten.

I wish to thank Martyn Low and Marcus Ng for pointing me to some important archival material, and Yu-Mei Balasingamchow for comments on the draft.

Faris Joraimi is a former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow with the National Library, Singapore (2022). As a writer and researcher specialising in the history of the Malay World, he has authored various essays for print and electronic media. Faris graduated with a Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in History from Yale-NUS College.

Faris Joraimi is a former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow with the National Library, Singapore (2022). As a writer and researcher specialising in the history of the Malay World, he has authored various essays for print and electronic media. Faris graduated with a Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in History from Yale-NUS College.NOTES

-

Johor’s borders had been cemented in the 1855 Anglo-Johor Treaty. Its sovereignty was legally established in a case involving Sultan Abu Bakar and Englishwoman Jenny Mighell, who sued him for breaching a marriage contract, but lost because the Foreign Office recognised Abu Bakar as a “foreign ruler” and therefore fell outside the jurisdiction of British courts. The Johor Constitution, or Undang-undang Tubuh Kerajaan Johor, was introduced in 1895. ↩

-

“Summary of Home News,” Straits Independent and Penang Chronicle, 13 August 1890, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Rounsevelle Wildman, Tales of the Malayan Coast: From Penang to the Philippines (Boston: Pothrop Pub., c.1899). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 398.2 WIL) ↩

-

Wildman, Tales of the Malayan Coast, 289–90. ↩

-

“In the Malacca Straits,” Singapore Free Press, 31 October 1891, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Editorials,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 13 July 1892, 7 (From NewspaperSG). If the Colony was absent, the Straits Times warned, Johor officials might have to “explain casually that attached to Johore there is a port called Singapore”. ↩

-

“Editorials.” ↩

-

“A Malay Village at the World’s Fair,” Sun 59, no. 283 (9 June 1892): 3, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030272/1892-06-09/ed-1/seq-3/. ↩

-

“Sultan of Johore,” Roanoke Times 10, no. 282 (12 August 1892): 2, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86071868/1892-08-12/ed-1/seq-2/. ↩

-

“The Sultan of Johore,” Evening Star, 24 March 1893, 7, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1893-03-24/ed-1/seq-7. ↩

-

“Tribute to Mr. Wildman,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 14 March 1893, 7 (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Rajah Rahman,” Singapore Free Press, 27 May 1893, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Wednesday, 22nd February,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 28 February 1893, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Rajah Rahman.” ↩

-

“Correspondence,” Singapore Free Press, 7 March 1893, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Clippings,” Sioux County Journal, 22 December 1892, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/2018270201/1892-12-22/ed-1/seq-2/; Indian Chieftain, 22 December 1892, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83025010/1892-12-22/ed-1/seq-1/; Barton County Democrat, 22 December 1892, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83040198/1892-12-22/ed-1/seq-2/; “Sultan of Johore Coming,” Philipsburg Mail, 8 June 1893, 7, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83025320/1893-06-08/ed-1/seq-7/. ↩

-

“Correspondence.” ↩

-

“On the Average Man,” Singapore Free Press, 14 March 1893, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Rajah Rahman.” ↩

-

World’s Columbian Exposition and Frederic Ward Putnam, Official Catalogue of Exhibits on the Midway Plaisance (Chicago: W.B. Conkey, 1893), 6, https://scholarship.rice.edu/jsp/xml/1911/22074/1/aa00144.tei.html. ↩

-

Hermann Heinze, Souvenir Map of the World’s Columbian Exposition at Jackson Park and Midway Plaisance, Chicago, Ill, U.S.A. 1893, 1892, map, 57 cm × 63 cm, https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4104c.ct002834/?r=-0.935,-0.018,2.871,1.084,0. ↩

-

Souvenir Map of the World’s Columbian Exposition at Jackson Park and Midway Plaisance, Chicago, Ill, U.S.A. 1893. ↩

-

“Pictures of Johore,” Singapore Free Press, 7 March 1893, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Johore Tea,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 25 January 1893, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The Official Directory of the World’s Columbian Exposition (Chicago: W.B. Conkey, 1893), 70, https://archive.org/details/officialdirector00worl. ↩

-

“True Tale of Johore,” Singapore Free Press, 19 September 1893, 190. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Paul Greenhalgh, Fair World: A History of World’s Fairs and Expositions, from London to Shanghai 1851–2010 (Winterbourne: Papadakis, 2011), 128. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R907.4 GRE) ↩

-

The names of the “natives” brought to Chicago for the Johor village and the much-larger Javanese village have not surfaced in my research. However, we do know of one Malayan who died after being sent to the British Empire Exhibition of 1924. This was Halimah Abdullah, a woman from Johor and master-weaver. She contracted pneumonia and died on 7 May 1924, aged 60. See Erika Tan, “The Forgotten Weaver,” accessed 12 July 2022, http://theforgottenweaver.blogspot.com/. ↩

-

Julian Hawthorne, “Foreign Folk at the Fair,” Cosmopolitan 15, September 1893, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015009215891. ↩

-

Melissa Rinehart, “To Hell with the Wigs! Native American Representation and Resistance at the World’s Columbian Exposition”, American Indian Quarterly 36, no. 4 (2012): 403. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Kimberly Kutz Elliott, “The World’s Columbian Exposition: The White City and Fairgrounds,” Smarthistory, 9 July 2021, https://smarthistory.org/white-city-and-fairgrounds/. ↩

-

Official Directory of the World’s Columbian Exposition, 12. ↩

-

“Johore at the World’s Fair,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 17 October 1893, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Sultan of Johore,” Singapore Free Press, 26 September 1893, 201. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

A. Rahman Tang Abdullah, Hikayat Johor dan Tawarikh Almarhum Sultan Abu Bakar: Kajian, Transliterasi dan Terjemahan Bahasa Inggeris (Johor Bahru: Yayasan Warisan Johor, 2011), 125. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.51092 ARA) ↩

-

See Lily Zubaidah Rahim, The Singapore Dilemma: The Political and Educational Marginality of the Malay Community (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 305.8992805957 LIL) ↩