Singapore's Stone Tools

Stone tools have been found in and around Singapore since the late 19th century. Much about them remains a mystery.

By Foo Shu Tieng

Much of the archaeological research on Singapore since the 1980s – whether land-based or maritime – has focused on historic periods, particularly the era from the 14th to the 20th centuries.1 However, scholars have long suspected that the islands that make up Singapore might have been occupied several thousand years ago and that stone tools may provide the evidence for that period.2

Stone tools are stones that often bear the characteristics of being deliberately shaped and/or use marks.3 Stone tools were initially attributed to male-hunting activities, but studies have since shown that hunting methods were gender-neutral.4

In Malaya, stone tools were found and reported during the colonial period, and were subsequently collected and deposited in museums.5 These tools were studied and described, and theories were proposed as to which type of stone tools came first. Many of these early studies, which relied on relative dating, had to be reassessed after the advent of radiometric dating.6 Malaya only began to use radiometric dating techniques for archaeological sites in 1960.7

Stone tools are usually not directly dated as this would only give an indication of when the rock was formed but not necessarily when the rock was manipulated and shaped. However, organic materials such as wood or shell might be found in the same excavation pit and dated based on their relative position to the stones. This is why finding artefacts in a non-disturbed context is vital.

That said, there are some very old sites with stone tools found in Malaysia, and their discovery also raises the question as to how old the sites in Singapore might be. In 2008, archaeologists in Lenggong Valley, Perak, uncovered tools that may date back to an astounding 1.83 million years. For reference, the oldest stone tool site in the world is in West Turkana, Kenya, which is about 3.3 million years old.8

It is generally thought that stone tools found in this region, and around the world, functioned in a similar fashion to modern-day axes and were used for wood working.9 In addition, we can see how stone tools are being used today to get a sense of how they might have been used in the past. Based on ethnographic literature, stone tools in Peninsular Malaysia are used in a variety of ways. Depending on their shape, stone tools could be used for root pounding, iron working, as whetstones to sharpen other tools, or as files for smoothening teeth.10 Rocks are used in fires (for example, to stabilise cooking pots or to contain the fire) or for roasting grain.

There is also evidence to show that rocks were used by Orang Asli groups, such as the Temuan and Semai, as an afterbirth procedure where the heated stones were wrapped in a specific kind of leaf and placed on the body of new mothers during the three days after giving birth. In addition, stones were also used for lighting fires, as projectiles, and even as medicine or for magical purposes.11

Stone Tools in Singapore and Johor

In Singapore, stone tools were found in Tanjong Karang (now Tuas) and on Pulau Ubin. H.N. Ridley (Henry Nicholas Ridley), the director of the Botanic Gardens, first reported the discovery of a round axe at Tanjong Karang in 1891.12 The precise location of the stone tool was not described in publications although Ridley’s personal papers or museum records may provide further clues.13 Unfortunately, subsequent development work in the area means that the soil in the vicinity would have likely experienced major disturbances, making it less viable for further research.14

One estimate of the stone artefact which Ridley found dates it to 4,000 BCE, but this was based on the type of stone tool rather than a radiocarbon date.15 As Southeast Asia is one of the regions where stone tools continued to be used by certain segments of the indigenous population even until quite recently, the round axe could also be much younger.16

In 1919, several stone implements of varying sizes were discovered in Johor’s Tanjong Bunga by Engku Abdul Aziz bin Abdul Majid, the 6th Menteri Besar of Johor.17 The location of Tanjong Bunga across the straits in Johor was close enough to Tanjong Karang in Singapore that Roland St John Braddell – a prominent lawyer and scholar of Malayan history – suggested in a 1936 paper in the Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society that there was a “stone-age portage” between Johor and Singapore, linking the sites of Tanjong Karang in Singapore and Tanjong Bunga in Johor in 1936.18 This theory has yet to be tested.

The artefacts at Tanjong Bunga were described as “lying on white clay within twenty feet of the bank”, and Engku Abdul Aziz had suggested that the stone tools surfaced due to beach erosion resulting from the construction of the Causeway.19 However, this is highly unlikely as a 2004 study highlighted that the initial Causeway construction led to low tidal energy in the Johor Strait instead; this indicates that the beach erosion would have occurred prior to 1919.20

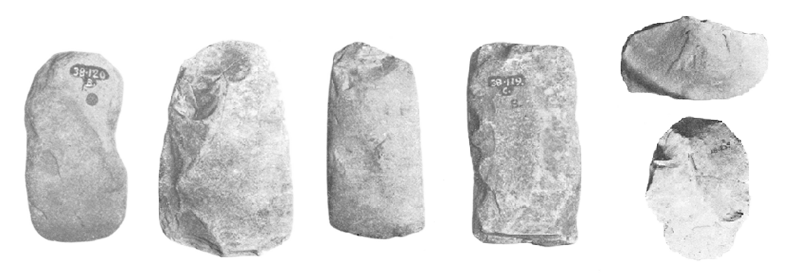

No dates were attributed to the Tanjong Bunga stone tools but P.V. van Stein Callenfels (Pieter Vincent van Stein Callenfels),21 a well-known prehistorian, had identified the two smaller stones as “neoliths”, suggesting that they were of a later date associated with domesticated plants and the use of pottery.22

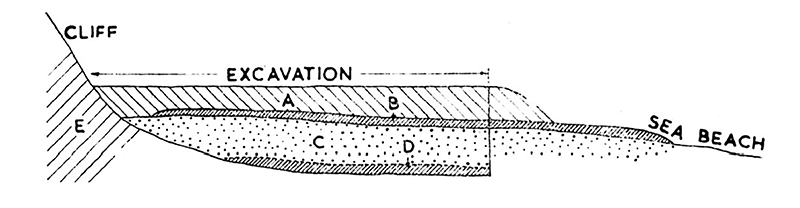

M.W.F. Tweedie (Michael Wilmer Forbes Tweedie), former director of the Raffles Museum in Singapore, who published a paper in 1953 on stone tools found in Malaya, similarly described the Tanjong Bunga stone tools as “neolithic blanks” – meaning that these could be further modified further into a specific tool form. He further described two of the artefacts as “round-axes” and added that one of the two artefacts was ground at one end. Tweedie’s diagram of Collings’ Tanjong Bunga excavation site further indicates that artefacts were also found in the lower layer of peat. The discovery of artefacts in these two layers suggests two different periods of site occupation.23

H.D. Collings (Herbert Dennis Collings), who later became the Curator of Anthropology at the Raffles Museum, visited Tanjong Bunga in 1934 and 1935, and upon finding more implements, conducted an excavation at the site in 1938. This was the first archaeological excavation undertaken at the southern end of the Malay Peninsula. At Tanjong Bunga, Collings found more “small ground neolithic axes, flakes, pieces of haematite, resin and quartz microliths” approximately 90 cm below the surface.24

The excavated artefacts at the site were described as being found in a stratigraphic layer between two layers of mangrove peat, and it was suggested that this soil layer might have been formed “during a slight temporary advance of the sea”.

Although there was no method of dating sea level changes back then, one recent study for Singapore suggested that the sea level rose to a maximum at around 3,150 BCE before falling to present levels.25 This new data might present the best educated guess for when the site was in use until further environmental history studies can be made near or at Tanjong Bunga itself.

Other surface finds reported by Collings consisted of a round axe, four small neoliths and a quadrangular (four-sided) neolithic adze (a versatile cutting tool with an angled hoe-like blade). Given that these were surface finds, however, they may not have been from the same occupation period as the excavated finds.26

A 2018 review of the Tanjong Bunga stone tools asserted that the site bore evidence of a prehistoric adaptation to a mangrove environment, which is relatively rare for Peninsular Malaysia, as mangroves are found only in certain parts of the Peninsula.27 The study also reaffirmed that the round axes at Tanjong Bunga were unlike those found in other sites in Peninsular Malaysia and were closer to those found in Island Southeast Asia. Similar round axes have been reported in Japan, India, Myanmar, Manchuria, Korea, Taiwan, North Vietnam, the Philippines, Melanesia and Micronesia. In Indonesia, the majority of the finds were in the eastern end of the archipelago although some were also reported at a few sites in Sumatra.28

On paper, the wide distribution would suggest that these stone tools were not geographically restricted. However, a visual comparison of the “round axes” depicted in published photographs from Singapore and Johor, and those suggested for Indonesia, indicates that there are quite a few differences. A more advanced technical study that investigates the life cycle of these artefacts may be more useful than the previous descriptive method of analysing these tools.29

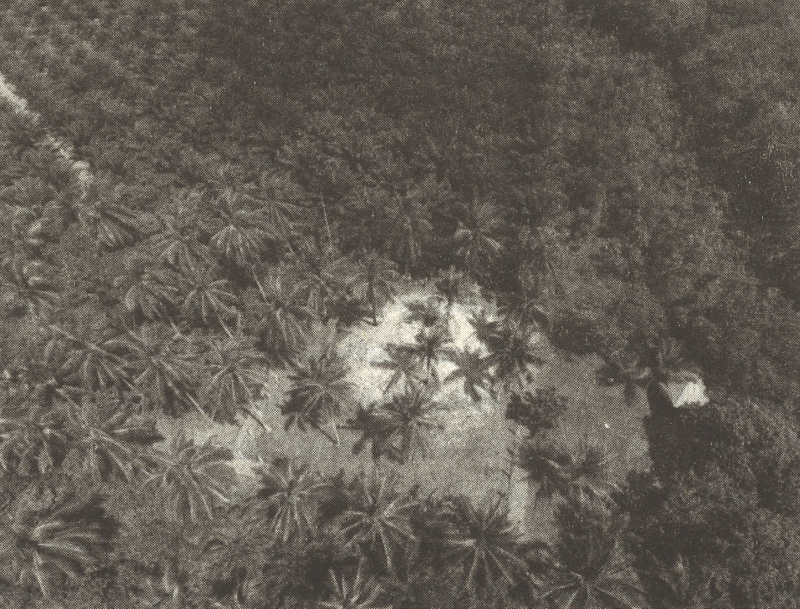

In addition to the Tanjong Bunga and Tanjong Karang areas, stone tools have also been found on Pulau Ubin. P.D.R. Williams-Hunt, Advisor on Aborigines for the Federation of Malaya,30 reported the existence of several stone artefacts (more round axes and stone flakes) at a site called Tanjong Tajam on the western end of Pulau Ubin, and the find was made public in October 1949.31 Williams-Hunt and Collings conducted an archaeological excavation at Tanjong Tajam in November 1949, but it was reported in 1951 that nothing of interest was found.32

In 2017, archaeologist David Clinnick and Sharon Lim, an assistant curator at the National Museum of Singapore, visited the Tanjong Tajam site. Although Clinnick reported finding a possible stone tool, a peer-reviewed article on this research has yet to be published and this finding cannot be confirmed.33

Stone Tools in Bintan

Stone tools were also reported in 2012 and 2014 at the Kawal Darat shell midden on the nearby island of Bintan. Shell middens are man-made heaps where the primary component are shell remains, the result of marine resource exploitation during its site-use period.34 This particular shell midden is known as Bukit Kerang Kawal Darat in Indonesian (BKKD).35 The site consists of a group of three shell mounds near the Kawal River.36

An initial radiocarbon date from one of the shell middens suggested that it was in use between the 5th and 10th centuries, making it relatively young. In comparison, the Pangkalan shell midden in Aceh in North Sumatra was utilised between 10,890 BCE and 1,780 BCE.37 The BKKD also existed much later than the Guar Kepah shell midden site in Penang, which dates back to between 3,800 BCE and 3,260 BCE.38

In 2012, an artefact made of andesite, a fine-grained igneous rock, was reported and found at BKKD in the same layer as plain earthenware fragments and Tridacna shells (Tridacna are a type of large saltwater clam). In 2014, artefacts made from quartzite and bauxite, as well as modified mollusc shells and bones, were reported.39

More significantly, part of a human jaw and calf bone were discovered on the eastern side of the shell midden, suggesting that there was a more complex use for the site rather than simply a depository for food waste.40 The researchers stated that the quartzite and bauxite artefacts were likely to be locally sourced and that the site was used as a food processing area, among other things.41

The BKKD site gives some indication as to how stone tools continued to be in use in the area until much later. This, however, raises the important question: were the tools found in Singapore from the Neolithic period, or much later? Another question that the BKKD raises is the identity of the people who might have made these tools. Although no human remains were found in association with the stone tools unearthed in Singapore and Johor, DNA analysis of the remains from the Bintan site may provide clues as to whether the stone tools might be traced to the Orang Laut (sea people) or to an even older and unknown prehistoric community.42

Stone Tools in Southeast Asia

The stone tools found in and around Singapore need to be understood within the wider context of the development of stone tools in Southeast Asia. The evolution of stone tools in this region differs from that in Europe.43

Southeast Asia reports a much lower incidence of microliths (small flaked stone tools measuring approximately 1 to 4 cm in length)44 and Acheulean handaxes,45 although this may be due to a paucity of data from open-air sites.46 (The Acheulean is a tradition of toolmaking that dates back to approximately 100,000 to 1.7 million years.)

Some researchers have argued that foragers and farmers in tropical environments like Southeast Asia would not have to rely so much on winter survival strategies compared to hunter-gatherers in temperate areas in capturing, processing and storing food leading up to winter. As such, the purpose of stone technologies may have been to make other tools that did not manage to survive the archaeological record.47

To explain the paucity of stone tools in this region, a “bamboo hypothesis” has been proposed. This theory suggests that the early inhabitants of the region relied on alternative materials like bamboo, wood or shell for more sophisticated tools. As these are made of perishable material or are thought of as being naturally occurring objects, they may not be as visible in the archaeological record.48

In the Thai-Malay peninsula, Pleistocene stone tools consisted of flaked cobbles (cobble-sized stone tools) as well as single and multi-platform cores.49 (The Pleistocene era lasted from 2.6 million years ago to 9,700 BCE.)50 The stone tool technology then transitioned to the Hoabinhian industry, which is characterised by Sumatraliths and flaked artefacts. Sumatrialiths are unifacially flaked cobble artefacts; this meant that enough material was removed from the core so that a single bevel formed the working edge of the tool. Flaked artefacts include objects such as points and scrapers, and these were made from the detached bits of stone from a core.51

The sites in Thailand with these types of artefacts date from the end of the Pleistocene to the mid-Holocene period (24,050 BCE to 1,200 CE).52 In Malaysia, a narrower timespan of approximately 16,000 BCE to 4,000 BCE is given.53

The stone tool technology then transitioned into highly polished stone adzes, axes and chisels, which some associate with the advent of pottery and agriculture (the Neolithic period), which for Peninsular Malaysia is said to be from approximately 4,000 BCE to 3,000 BCE.54

Further Research

There are possibilities for further research on the stone tools discovered in Singapore, particularly in terms of the excavation notes (if any are to be found) and the research methods. Given that radiometric dating was not conducted for the sites with the artefacts, it cannot be determined whether the tools were used or made much later for their healing and magical properties. (There is ethnographic evidence to suggest that stone tools may have had a secondary use as thunderstones associated with magic rituals [Indonesian/Malay: batu halilintar or batu lintar] and this may be part of a larger global phenomenon.55)

All the stone tool sites described earlier were either found along coastal or in brackish (mangrove) waters in Singapore. This raises the question: was there inland prehistoric activity for Singapore? Rivers would have been the general travel marker during early exploratory periods and tracing the old river courses may reveal more important sites. Should anyone stumble upon such a site in Singapore, do leave the site untouched, mark its GPS location and alert the National Heritage Board immediately as the context of the find is likely to be as important as the find itself. Keep your eyes peeled: you never know what you might find.

Stone Tools By Eras56

(Note: Present = 1950)

Holocene (11,800 years ago to the present; Post-Ice Age)

Example:

- Jenderam, Langsat Valley, Selangor, Malaysia: 3,650 years ago57

Pleistocene (2,588,000 to 11,800 years ago; the most recent ice Age)

Examples:

- Tham Lod, northwest Thailand: 40,000 to 14,000 years ago58

- Kota Tampan, Lenggong Valley, Perak, Malaysia: 70,000 years ago59

- Sangiran, Central Java, Indonesia: 1 million years ago60

- Current proposed oldest known stone tool site in SEA: Bukit Bunuh, Lenggong Valley, Perak, Malaysia (BBH2007): 1.83 million years ago61

- Current oldest known stone tool site in Asia: Shangchen (上陈), Shaanxi, China: 2.1 million years ago62

Pliocene (5,333,000 to 2,588,000 years ago)

Example:

- Current oldest known stone tool site: Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya: 3.3 million years ago63

Foo Shu Tieng is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections. Her responsibilities include collection management, content development as well as providing reference and research services. Her publications on ancient money, shell middens and salt can be found on ResearchGate.

Foo Shu Tieng is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections. Her responsibilities include collection management, content development as well as providing reference and research services. Her publications on ancient money, shell middens and salt can be found on ResearchGate.NOTES

-

John N. Miksic, Singapore & The Silk Road of the Sea: 1300–1800 (Singapore: NUS Press and National Museum Singapore), 209–63. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 MIK-[HIS]); The last in-depth publication that discusses stone tools in Singapore is Alexandra Avieropoulou Choo, Archaeology: A Guide to the Collections, National Museum Singapore, ed. Jane Puranananda (Singapore: National Museum of Singapore, 1987), 5–17. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 934.1074095957 CHO) ↩

-

Miksic, Singapore & The Silk Road, 217–18. ↩

-

When considering what is natural or shaped by hominins, the knowledge of fracture mechanics is important. See William Andrefsky Jr., Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Analysis, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 11. ↩

-

Michael Gurven and Kim Hill, “Why Do Women Hunt? A Reevaluation of ‘Man the Hunter’ and the Sexual Division of Labor,” Current Anthropology 50, no. 1 (February 2009), 51. (From EBSCOHOST via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

M.W.F. Tweedie, “The Stone Age of Malaya,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 26, no. 2 (162) (October 1953): 6–7. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); M.W.F. Tweedie, “The Malayan Neolithic,” Journal of the Polynesian Society 58, no. 1 (March 1949): 19–35. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website). Roger Duff, Stone Adzes of Southeast Asia: An Illustrated Typology (Christchurch: Canterbury Museum Trust Board, 1970). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 915.903 DUF) ↩

-

Mike J.C. Walker, Quaternary Dating Methods (England: J. Wiley, 2005). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R 551.701 WAL); Miriam Noel Haidle and Alfred F. Pawlik, “Missing Types: Overcoming the Typology Dilemma of Lithic Archaeology in Southeast Asia,” Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 29 (June 2009): 2–5, https://journals.lib.washington.edu/index.php/BIPPA/article/view/9470/0. ↩

-

Frederick L. Dunn, “Radiocarbon Dating the Malayan Neolithic,” The Prehistoric Society 32 (December 1966): 352–53, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0079497X0001447X. ↩

-

Sonia Harmand et al., “3.3 Million Year-old Stone Tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya,” Nature 521 (May 2015): 310–15, https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14464. ↩

-

David Clinnick and Sharon Lim, “In Search of Prehistoric Singapore,” Muse SG 10, no. 2 (2018): 40, https://www.roots.gov.sg/resources-landing/publications/education-and-community-outreach/Muse-SG-Vol-10-Issue-2. ↩

-

A. Terry Rambo, “A Note on Stone Tool Use by the Orang Asli (Aborigines) of Peninsular Malaysia,” Asian Perspectives 22, no. 2 (1979): 116–17. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Rambo, “Stone Tool Use,” 116–17. ↩

-

Tweedie, “Stone Age of Malaya,” 69; Urban Redevelopment Authority (Singapore), Tuas Planning Area: Planning Report 1996 (Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority, 1996), 8. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 711.4095957 SIN) ↩

-

Henry Nicholas Ridley, HN Ridley’s Notebooks, vols. 2–6, 1880–1909, National Library of Australia. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. M771) ↩

-

War Office, “The Singapore Naval Base,” 1924–1933, The National Archives, United Kingdom, 70. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. WO 106/132); Chia Lin Sien, Habibullah Khan and Chou Loke Ming, The Coastal Environmental Profile of Singapore (Manila: International Center for Living Aquatic Resources Management, 1988), 41. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 333.917095957 CHI); Urban Redevelopment Authority (Singapore), Tuas Planning Area, 11. ↩

-

Nancy Koh, “Seeing Old Singapore in a Lump of Clay,” Straits Times, 19 November 1987, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ian C. Glover, “Connecting Prehistoric and Historic Cultures in Southeast Asia,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 47, no. 3 (October 2016): 507. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); Rambo, “Stone Tool Use,” 116–17; Dietrich Stout, “Skill and Cognition in Stone Tool Production,” Current Anthropology 43, no. 5 (December 2002): 693–722. (From EBSCOhost via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Shaharom Husain, Sejarah Johor: Kaitannya Dengan Negeri Melayu (Shah Alam: Penerbit Fajar Bakti Sdn. Bhd, 1995), plate 20. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Malay R 959.5119 SHA); Engku Abdul-Aziz, “Neoliths from Johore,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 10, no. 1 (113) (January 1932): 159. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Roland Braddell, “An Introduction to the Study of Ancient Times in the Malay Peninsula and the Straits of Malacca,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 14, no. 3 (December 1936): 36. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website). ↩

-

Alvin Chua, “The Causeway,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2009. ↩

-

Michael Bird et al., “Evolution of the Sungei-Buloh-Kranji Mangrove Coast, Singapore,” Applied Geography 24, no. 3 (2004): 184, 192, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2004.04.002. ↩

-

“Most Famous Professor in Asia Dead,” Straits Budget, 5 May 1938, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tweedie, “Stone Age of Malaya,” 69. ↩

-

Tweedie, “Stone Age in Malaya,” 69, 85. ↩

-

Tweedie, “Stone Age in Malaya,” 69, 84–85. ↩

-

Stephen Chua et al., “A New Holocene Sea-level Record for Singapore,” The Holocene 31, no. 9 (June 2021): 1387, https://doi.org/10.1177/09596836211019096; Another study on Holocene sea levels within the Johor Strait only showed sea level rise between 7,550 BCE and 4,550 BCE. See Michael I. Bird et al., “An Inflection in the Rate of Early Mid-Holocene Eustatic Sea-Level Rise: A New Sea-level Curve from Singapore,” Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science 71, no. 3–4 (February 2007): 523, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2006.07.004. ↩

-

Tweedie, “Stone Age in Malaya,” 85. ↩

-

Ahmad Hakimi Khairuddin, “Penempatan Masyarakat Neolitik di Johor,” in Arkeologi Di Malaysia: Dahulu Dan Kini, ed. Asyaari Muhamad (Kuala Lumpur: Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 2018), 86–89. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Malay RSEA 939.595 ARK); Omar and Muhammad Affizul Misman, “Extents and Distribution of Mangroves in Malaysia,” in Status of Mangroves in Malaysia, ed. Hamdan Omar, Tariq Mubarak Husin and Ismail Parlan (Selangor Darul Ehsan: Forest Research Institute Malaysia, 2020), 12–37. ↩

-

H.R. van Heekeren, The Stone Age of Indonesia, 2nd edition (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1972), 165–67. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 991 VITLV-[GH]); Ketut Wiradnyana, “Artefak Neolitik di Pulau Weh: Bukti Keberadaan Austronesia Prasejarah di Indonesia Bagian Barat,” Naditira Widya 6, no. 1 (April 2012), 5–13, https://doi.org/10.24832/nw.v6i1.79. ↩

-

Hsiao Mei Goh, et al., “The Paleolithic Stone Assemblage of Kota Tampan, West Malaysia,” Antiquity 94, no. 377, e25 (October 2020): 1–9, https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.158; Michael J. Shott, “History Written in Stone: Evolutionary Analysis of Stone Tools in Archaeology,” Evolution: Education and Outreach 4 (2011): 435, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12052-011-0344-3. ↩

-

Elizabeth Moore, “The Williams-Hunt Collection: Aerial Photographs and Cultural Landscapes in Malaysia and Southeast Asia,” Sari – International Journal of the Malay World and Civilisation 27, no. 2 (2009), 268–69, http://journalarticle.ukm.my/1195/1/SARI27%5B2%5D2009_%5B12%5D.pdf; “The ‘Tuan Jangot’ Is Dead,” Straits Times, 13 June 1953, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tweedie, “Stone Age in Malaya,” 70; “Raffles Museum To Go Digging for Facts,” Sunday Tribune (Singapore), 23 October 1949, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

P.D.R. Williams-Hunt, “Recent Archaeological Discoveries in Malaya (1945–50),” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 24, no. 1 (154) (February 1951): 191. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Clinnick and Lim, “In Search of Prehistoric Singapore.” ↩

-

Gregory A. Waselkov, “Shellfish Gathering and Shell Midden Archaeology,” Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 10 (1987): 93–210. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Defri Elias Simatupang et al., “Ekskavasi Dan Kajian Manajemen Arkeologi Situs Bukit Kerang Kawal Darat di Kabupaten Bintan, Provinsi Kepulauan Riau,” Berita Penelitian Arkeologi 32 (Medan: Balai Arkeologi Sumatera Utara, 2017), 26, 33, http://repositori.kemdikbud.go.id/18820/; Taufiqurrahman Setiawan, “Melihat Kembali Nilai Penting Bukit Kerang Kawal Darat,” in Daratan dan Kepulauan Riau: Dalam Catatan Arkeologi dan Sejarah ed. Sofwan Noerwidi (Jakarta: PT. Pustaka Obor Indonesia, 2021), 85–97. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Malay RSEA 959.81 DAR) ↩

-

Ketut Wiradnyana et al., “Verifikasi dan Identifikasi Objek Arkeologi di Kepulauan Riau dan Sumatera Utara,” in Berita Penelitian Arkeologi 23 (Medan: Balai Arkeologi Medan, 2010), 9–12, 17–18, 30–33; Simatupang, “Ekskavasi Dan Kajian Manajemen,” 34, http://repositori.kemdikbud.go.id/8653/. ↩

-

Simatupang, “Ekskavasi dan Kajian Manajemen,” 57. The uncalibrated date for Kawal Darat was 1680±110 BP (around 300 CE). Ketut Wiradnyana, “Pentarikhan Baru Situs Hoabinhian dan Berbagai Kemungkinannya,” Sangkahala: Berkala Arkeologi 13, no. 26 (2010): 226, https://garuda.kemdikbud.go.id/documents/detail/602829. ↩

-

Mokhtar Saidin, Jaffrey Abdullah and Jalil Osman, “Masa Depan USM Dan Usu Dalam Penyelidikan Arkeologi Serantau,” in Prosiding Seminar Antarabangsa: Mengungkap Perabadan Asia Tenggara Melalui Tapak Padang Lawas Dan Tapak Sungai Batu, Kedah, ed. Mokhtar Saidin and Suprayitno (Medan: Pusat Penyelidikan Arkeologi Global, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 2011), 4; Zuliskandar Ramli, “Zaman Prasejarah Di Malaysia Dalam Konteks Peninggalan Masyarakat Pesisir Pantai,” Jurnal Arkeologi Malaysia 28 (2015): 36. ↩

-

Simatupang, “Ekskavasi Dan Kajian Manajemen,” 30–31, 42. ↩

-

Ryan Rabett et al, “Inland Shell Midden Site-formation: Investigation into a Late Pleistocene to Early Holocene Midden from Tràng An, Northern Vietnam,” Quaternary International 239, no. 1–2 (2011): 153–69, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2010.01.025. ↩

-

Defri Elias Simatupang, “Ekskavasi Dan Kajian Manajemen,” 66. ↩

-

J.R. Logan, “The Orang Sletar of the River and Creeks of the Old Strait and Estuary of the Johore,” Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia 1 (1847): 302–304. (From BookSG); Mariam Ali, “Singapore’s Orang Seletar, Orang Kallang, and Orang Selat: The Last Settlements,” in Tribal Communities in the Malay World: Historical, Cultural and Social Perspectives, ed. Geoffrey Benjamin and Cynthia Chou (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2002), 273–93. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 305.8959 TRI) ↩

-

Adnan Jusoh, Mokhtar Saidin and Zuliskandar Ramli, “Zaman Paleolitik, Hoabinhian Dan Neolitik di Malaysia,” in Prasejarah Dan Protosejarah Tanah Melayu, ed. Nik Hassan Shuhaimi Nik Abdul Rahman and Zuliskandar Ramli (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 2018), 21–90. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Malay RSEA 930.109595 PRA); David Bulbeck, “An Integrated Perspective on the Austronesian Diaspora: The Switch from Cereal Agriculture to Maritime Foraging in the Colonisation of Island Southeast Asia,” Australian Archaeology no. 67 (December 2008): 44. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); Matthew R. Goodrum, “The Idea of Human Prehistory: The Natural Sciences, the Human Sciences, and the Problem of Human Origins in Victorian Britain,” History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 34, nos. 1–2 (2012): 140–41. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

“Introduction to Archaeology: Glossary”, Archaeological Institute of America, accessed 1 August 2022, https://www.archaeological.org/programs/educators/introduction-to-archaeology/glossary/. ↩

-

“Introduction to Archaeology” and Ignacio de la Torre, “The Origins of the Acheulean: Past and Present Perspectives on a Major Transition in Human Evolution,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 371, no. 1698 (July 2016):1–5, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0245. ↩

-

Robin Dennell, “Life Without the Movius Line: The Structure of the East and Southeast Asian Early Paleolithic,” Quaternary International 400 (May 2016): 14–22, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.09.001. ↩

-

Graeme Barker, Tim Reynolds and David Gilbertson, “The Human Use of Caves in Peninsular and Island Southeast Asia: Research Themes,” Asian Perspectives 44, no. 1 (Spring 2005): 6 (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Adam Brumm, “The Movius Line and the Bamboo Hypothesis: Early Hominin Stone Technology in Southeast Asia,” Lithic Technology 35, no. 1 (Spring 2010): 8 (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

A core refers to the source stone that you can remove one or more flakes from through a process called knapping (think of it as the source stone from which you can make new stone tools by chipping bits off). Platforms refer to the surface area that shows the impact of the detachment strike. See Andrefsky, Lithics, 254, 262. ↩

-

The Pleistocene is a geological epoch that roughly corresponds with the most recent Ice Age and is dated from approximately 2.6 million years ago to 9,700 BCE. See Brad Pillans and Philip Leonard Gibbard, “The Quaternary Period,” in The Geologic Time Scale (Oxford, U.K.: Elsevier, 2012), 979. ↩

-

Flaked artefacts refer to a portion of rock detached from a core either by percussive flaking or pressure flaking. See Andrefsky, Lithics, 255. ↩

-

The Holocene is the current geological epoch, which began at approximately 9,700 BCE. It refers to a time after the most recent Ice Age. See Pillans and Gibbard, “Quaternary Period,” 999–1000. ↩

-

David Bulbeck and Ben Marwick, “Stone Industries of Mainland and Island Southeast Asia,” in The Oxford Handbook of Early Southeast Asia, ed. Charles F.W. Higham and Nam C. Kim (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), 126, 131. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.01 OXF); Rasmi Shoocongdej, “The Hoabinhian: The Late and Post-Pleistocene Cultural Systems of Southeast Asia,” in The Oxford Handbook of Early Southeast Asia, ed. Charles F.W. Higham and Nam C. Kim (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), 156. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.01 OXF); Jusoh, Saidin and Ramli, “Zaman Paleolitik,” 27. ↩

-

Tweedie, “Stone Age in Malaya,” 6; Jusoh, Saidin and Ramli, “Zaman Paleolitik,” 36. ↩

-

Adam Brumm, “Lightning Teeth and Ponari Sweat: Folk Theories and Magical Uses of Prehistoric Stone Axes (and Adzes) in Island Southeast Asia and the Origin of Thunderstone Beliefs,” Australian Archaeology 84, no. 1 (2018), 37–55 ; Joseph Needham, Science & Civilisation in China Vol. III (London: Cambridge University Press, 1959), 434 (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R 509.51 NEE); Edwin O. Reischauer, “The Thunder-Weapon in Ancient Japan,” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 5, no. 2 (June 1940), 137–41. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); Yi Seonbok, “‘Thunder-Axes’ and the Traditional View of Stone Tools in Korea,” Journal of East Asian Archaeology 4 (2002), 294–306; Matthew R. Goodrum, “Questioning Thunderstones and Arrowheads: The Problem of Recognizing and Interpreting Stone Artifacts in the Seventeenth Century,” Early Science and Medicine 13, no. 5 (2008), 482 (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); Tomasz Kurasiński, “Against Disease, Suffering, and Other Plagues: The Magic-Healing Role of Thunderstones in the Middle Ages and Modern Times,” Fasiculi Archaeologiae Historicae 34 (2021), 9–10, https://doi.org/10.23858/FAH34.2021.001. ↩

-

Brad Pillans and Philip Leonard Gibbard, “The Quaternary Period,” in The Geologic Time Scale (Oxford, U.K.: Elsevier, 2012), 981, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279428084_The_Quaternary_Period. ↩

-

Leong Sau Heng, “Jenderam Hilir and the Mid-Holocene Prehistory of the West Coast Plain of Peninsular Malaysia,” Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association Bulletin 10 (1991): 153; Stephen Chia, “Archaeological Evidence of Early Human Occupation in Malaysia,” in Austronesian Diaspora and the Ethnogenesis of People in Indonesian Archipelago, ed. Truman Simanjuntak, Ingrid H. E. Pojoh and Mohammad Hisyam (Jakarta: Indonesian Institute of Sciences; International Center for Prehistoric and Austronesian Studies; Indonesian National Committee for UNESCO, 2006), 241–43. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.8 INT) ↩

-

David Bulbeck and Ben Marwick, “Stone Industries of Mainland and Island Southeast Asia,” in The Oxford Handbook of Early Southeast Asia, ed. Charles F.W. Higham and Nam C. Kim (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), 128. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.01 OXF) ↩

-

Hsiao Mei Goh, et al., “The Paleolithic Stone Assemblage of Kota Tampan, West Malaysia,” Antiquity 94, no. 377, e25 (October 2020): 1, Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.158. ↩

-

Truman Simanjuntak, François Sémah and Claire Gaillard, “The Paleolithic in Indonesia: Nature and Chronology,” Quaternary International 223, no. 3 (2010): 418, http://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2009.07.022. ↩

-

Hubert Forestier, et al., “The First Lithic Industry of Mainland Southeast Asia: Evidence of the Earliest Hominin in a Tropical Context,” L’Anthropologie 126, no. 1 (January–March 2022), 102996: 32, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anthro.2022.102996. ↩

-

Zhaoyun Zhu et al., “Hominin Occupation of the Chinese Loess Plateau since about 2.1 Million Years Ago,” Nature 559 (11 July 2018), 608–12, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-018-0299-4. ↩

-

Sonia Harmand et al., “3.3 Million Year-old Stone Tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya” Nature 521 (May 2015), 310–15, https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14464. ↩