In Their Own Voices: Preparing for War in Singapore

Before the fall of Singapore in 1942, people prepared for the imminent war by stockpiling food, building air raid shelters and volunteering in civil defence units.

By Christabel Khoo and Mark Wong

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a stark reminder that even today, wars still break out. Russia’s relentless attack on Ukrainian cities also drives home the point that combat does not only involve soldiers; the civilian population also ends up suffering deeply, whether as a by-product of fighting, or as a deliberate strategy.

This is something that the population in Singapore learnt at their great cost some eight decades ago. The first Japanese bombs dropped on Singapore on 8 December 1941, and the bombing continued unabated throughout the Japanese army’s Malayan campaign. Conditions in Singapore worsened when the Japanese crossed the Strait of Johor in early February 1942, and pitched battles were fought on the island itself. Finally, on 15 February 1942, the British surrendered, which ushered in over three years of misery in Japanese-occupied Singapore.

This year, 2023, marks the 81st anniversary of the fall of Singapore. With each passing year, we lose more and more of the generation of people who had survived the war. One way that society has tried to ensure that the stories and lessons of this period are not forgotten is through oral history.

Oral history is powerful. Not only can stories of the past be preserved in their factual detail, but the voices of witnesses convey complex emotions that are difficult to express in the written word.

Over the last eight decades, military historians have examined how the Japanese were able to prevail against a much larger British military force. The travails of the Japanese Occupation period have also been well documented. However, one aspect of the war has not been as well studied – how people in Singapore prepared for the worst in the months prior to and even as bombs and artillery shells began to rain on the island.

This essay highlights first-person accounts from the oral history collection of the National Archives of Singapore to give an insight into life in Singapore before the first bombs fell on the island on 8 December 1941 to the British surrender on 15 February 1942.

Stockpiling Food

One of the first things many people did was to stockpile food. In early 1941, the British authorities had initially encouraged the people to build stockpiles. However, when prices began rising due to shortages and profiteering, the authorities tried to discourage stockpiling, but it did not work.1

Toh Mah Keong was a 20-year-old student from Penang who had come to Singapore for his education. He recalled that people began stocking up on canned food. “[Y]ou’ll find that everybody’s house you visit there’ll be cases of sardines. … You’ll find, as you walk around the streets in the evening, going home in buses, everybody carrying parcels or baskets of provisions.”2

Canned sardines were a popular item that people hoarded. Soh Guan Bee, who was 13 at the time, said that as a result of the war, he developed a lifelong dislike for sardines. “We got sardines… Practically, it’s sardines and nothing else… Till today I dare not eat sardine, I see sardine I get sad.”3

Medical doctor Tan Ban Cheng, then also 13 years old, recalled how his family’s stockpile became the only source of food they had for weeks before the surrender: “[T]owards the end that’s all we had to live on, the tin foods and whatever food we had… at least two to three weeks before the surrender, most of us could not get any food from outside. We had to depend on whatever food we had.”4

Escaping to the Countryside

Tan Guan Chuan, who was in government service and a volunteer with the Air Raid Precautions, observed how people fled to the countryside when the first bombs fell on 8 December 1941. “You find cars running from the city all right up to the remote parts of Singapore to escape from the bombs that were dropping… everybody just [took] their families and [drove] to any relations who are staying far away from the city.”5

Among them was Abdealli K. Motiwalla and his family, who moved out of Raffles Place to Yio Chu Kang Road. At the time, they were living near the shop where Motiwalla was working, a shop that his grandfather had established in 1886. He recalled: “[E]verybody was running away and then people were running and people thought now the war has started, we shall have to leave the city, go outside city… people thought will be more safe because bombing will take place in the city.”6 Motiwalla’s family rented a bungalow in Yio Chu Kang but he continued travelling to Raffles Place every day to work at the shop until the Japanese entered Singapore.

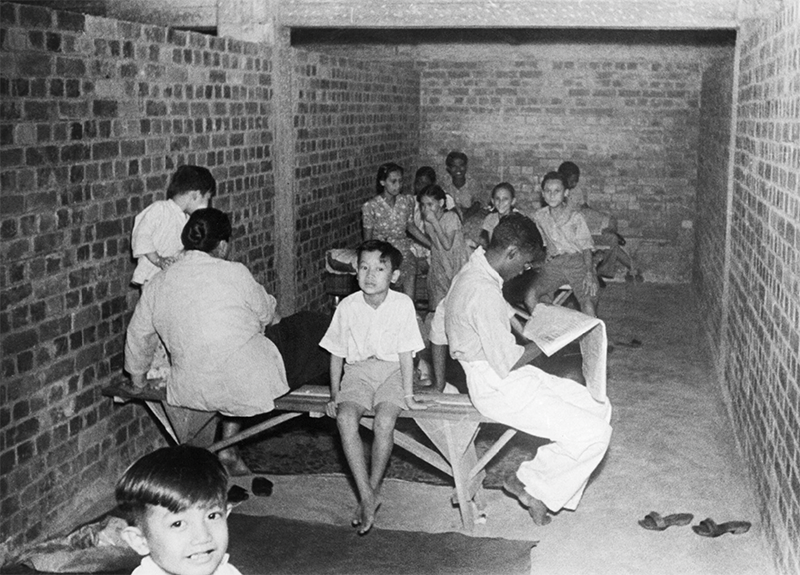

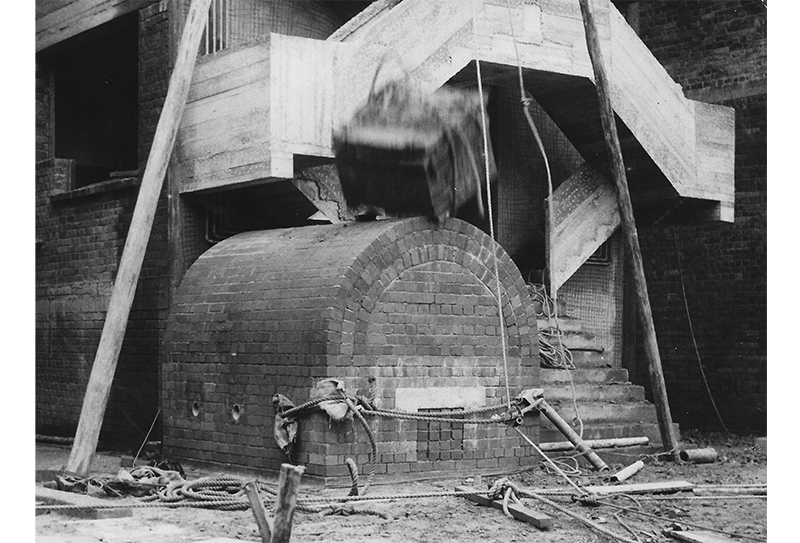

Building Air Raid Shelters

In their Yio Chu Kang compound, Motiwalla’s family had built an underground air raid shelter made of bricks. Although originally meant for the family, they generously opened it to others. “[N]ext door people used to come also. And they had also their own shelters, different compound. They had their own, also they had made. But in my place it was quite big, so many people used to come,” recalled Motiwalla.7

Across the island, many people were building their own air raid shelters. The British colonial government had initially adopted a “stay put” policy. In May 1939, they announced that “the best thing to do in an air raid would be for citizens to remain in their homes”, as shelters and evacuation camps were considered impracticable.8 By May 1941, owing to public pressure, the government changed their stance and published notices in newspapers informing the people that they could register for accommodation in evacuation camps. These, however, were intended for the “poorer classes among the population”.9

By September 1941, there were still no public air raid shelters. A government notice tried to explain this by saying that the low, flat land of Singapore with water near the surface rendered underground shelters impossible. It also said Singapore’s large population of half a million, as well as narrow streets, made air raid shelters impractical.10

Instead, the notice recommended an open grassy place as the safest option, urging people to “find out where the nearest open space is, and make for that in air raid”. The government assured the people that the “publication of this notice need cause no alarm” and “it does not mean that Government is expecting war to break out in this part of the world at present. On the contrary, the position in the Far East at the moment is calmer than it has been for several months past”.11

But barely three months later, the first bombs rained down on Singapore. Lee Tian Soo, then a 16-year-old boy living in Chinatown, recounted that when the first bombs fell, people “started to rush everywhere, anywhere, those people found any ground they started to build air raid shelters, that was the time. Everybody seemed to be busy, building shelters”.12

Tan Geok Koon and his family, who were living on Thomson Road, built their own air raid shelter that could accommodate about 20 people. “There was a hill behind my house, so we dug about eight feet tall and in a semi-circle, about – five or six feet wide and in a semi-circle form. And at the top of it, [we] put a lot of planks and also sandbags and all that we did by ourselves, or rather we call a few of the Malay villages to do it, and so that is how we had the shelter.”13

Not everyone was fortunate enough to have land for a shelter. Chu Shuen Choo (Mrs Gay Wan Guay), who was then a teacher living in Katong, had to make do with whatever available space she had. “[M]y shelter was just underneath the staircase and a table,” she recalled. “So whenever we hear the siren, I would take my flask of milk with my baby and carry her downstairs and go under the table.”14

Evacuating Overseas

Those who had the means evacuated overseas to countries such as India, Indonesia and Australia. Municipal Commissioner Rajabali Jumabhoy, who was also president of the Indian Chamber, recalled that as soon as the Japanese attacked, the British were the first to leave, especially the civilians, their wives and children.15

Jumabhoy was one of those in charge of the evacuation of Indians, but there were no ships available. “So I as President of the Indian Chamber of Commerce cabled Gandhiji [Mahatma Gandhi] and Lord Wavell [Archibald Percival Wavell, then Viceroy of India] and were sent four ships. Very few could leave, say about 5,000 and no more. I had to take the last ship. Mr Tan Chin Tuan was I think in charge of Chinese evacuees and he helped quite a bit to leave Singapore. Mostly the well-to-do people left from here and also Malaysia.”16

Jumabhoy sent his wife and children away on 21 January 1942, but he remained in Singapore as the governor felt that Jumabhoy’s departure would affect the morale of the Indian public. Later, fearing reprisal from the Japanese as he had held high positions under the British,17 Jumabhoy took the last boat leaving for India on 7 February 1942 with “1,000 Indians and 52 non-Indians”.18

Not everyone chose to evacuate, even if they had the opportunity. There were those like Ibrahim Isa, then a part-time announcer with the Malaya Broadcasting Corporation (MBC). “No, I never made any preparations [to leave Singapore],” he said. “Although the MBC, they offered their staff, those who wanted to evacuate, they were prepared to take them. But I think, no Malay staff prepared to leave Singapore. I think one or two Chinese staff were forced to leave Singapore.”19

Participating in Civil Defence

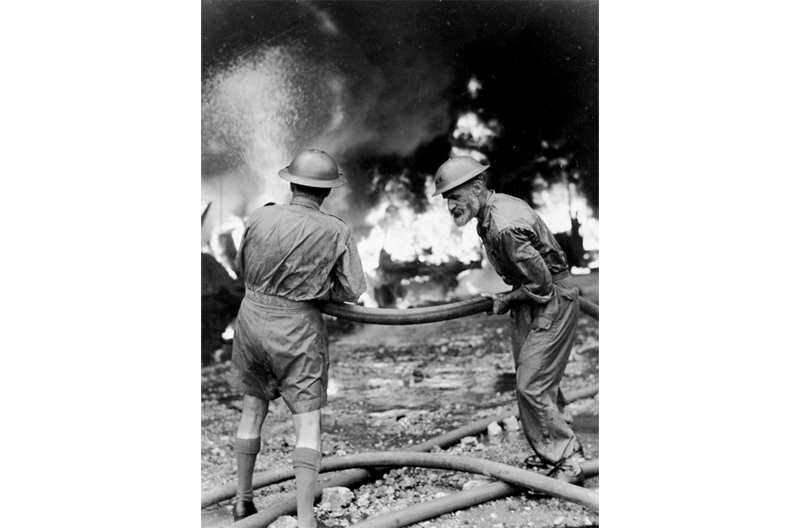

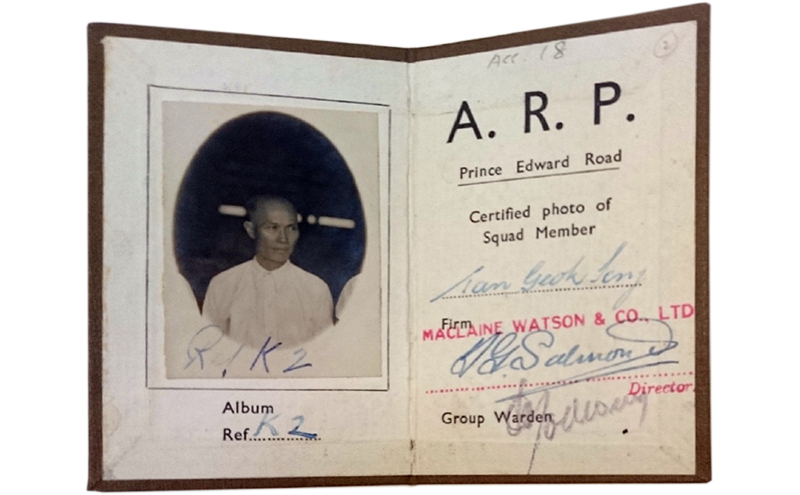

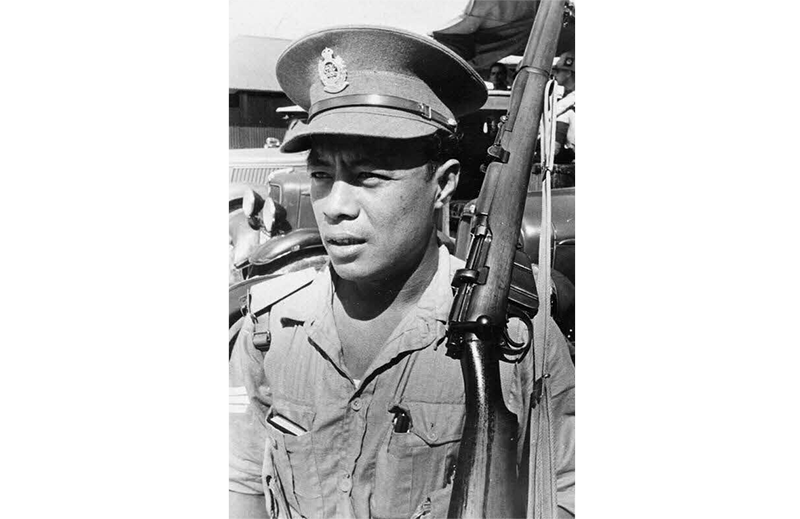

The recruitment of volunteers for civil defence units began in 1939. These civil defence units, which started conducting training, included the Air Raid Precautions (ARP), Medical Auxiliary Service, Observer Corps, Fire-fighting Squad and the Special Constabulary. Some 6,000 men and women volunteered.20

Ang Seah San, a bookkeeper at Lexus Borneo Motors Limited, was chosen by his company to attend Passive Defence Services training in the beginning of 1941. He attended a crash course in firefighting and first aid. He also learned how to manage public behaviour and “what precautions to take in order to minimise injuries to persons and damages to properties”.21

Ang recalled practising air raid drills. When the air raid siren sounded, “wardens on duty were ordered to patrol the streets… householders would comply with our instructions, such as the taking of cover in the shelter and switching off the lights at night, advising pedestrians to cover, to take cover wherever possible. Vehicles travelling on the road were ordered to park by the roadside with lamps, headlamps switched off… In order that the public might be acquainted with the requirements, these exercises had been continually practised for about a month or so”.22

Teacher Gay Wan Guay joined the ARP soon after the war started. His job was to “tell people, especially in the outlying areas in Tuas and Jurong and Woodlands and so on, to move away from the Johor Straits as the Japanese were advancing”. But he found it difficult to persuade people to leave their farms, pigs and poultry behind.23

Lee Kip Lee (who later became Honorary Life President of The Peranakan Association Singapore and was the father of singer-songwriter Dick Lee) was in his last year at Raffles College just before the British surrender of Singapore. He volunteered with the Medical Auxiliary Services Unit in Raffles College at the beginning of 1941. He recounted that they were basically trained to provide first aid: “So, we were taught first aid and we were divided into groups… And the government provided us with, with one or two ambulances which were actually converted Singapore Traction Company omnibuses … not the real ambulances.”24

Students also had to participate in air raid drills in school. Mani Letchumanan Masillamani recalled practising such drills after war was declared in Europe in 1939. Interestingly, the drills changed over time. Initially, everyone would go to the edge of the classroom and lie down with the head touching the wall, legs turned facing up. He said: “Then we were asked to put the hand like that [over forehead and eyes]… One month later, they changed the thing. Now what happened, they say, ‘You must face down’.”25

Masillamani also remembered that his school asked for used exercise books and how that meant forgoing the kacang puteh he used to get in exchange for them. “[T]hese all were all given away to them for collection, will be used as material, useful material, as part of the war effort… In those days, we sell it to the kacang puteh [peanut] man, he will give you one packet of kacang puteh in those days.”26

In 1941, the Department of Supply had organised a series of “salvage weeks” where scraps of all kinds were collected for disposal as part of Singapore’s war effort. Besides paper, people also donated pots, pans, kettles, hat pegs, coat hangers, shoe trees, bathroom fittings, brass ornaments, cigarette boxes and cigar humidors.27

Soh Chuan Lam, a Standard VII (equivalent to Secondary 2) student at St Joseph’s School collected scrap iron. He said: “[T]here was a shortage of iron…. So on certain days of the week, we were allowed to leave the school and go around collecting scrap iron and took them to the school for the government to take them away.”28

Preparing for Combat

Some people decided that they would learn to take up arms to fight. One option for them was to join the Singapore Volunteer Corps (SVC).

The SVC had its roots as the privately funded Singapore Volunteer Rifle Corps in 1854, before becoming a public organisation a few years later. The SVC had played an important role in quelling civil disturbances and preserving the security of the island – duties such as operating defence lights and manning harbour defences during World War I. It was known by various names, including the Singapore Volunteer Artillery and the Straits Settlements Volunteer Force.29

Prior to the Japanese invasion, large-scale training in Singapore was held for the Straits Settlements Volunteer Force, which was made up of the respective volunteer corps in Singapore (two battalions), Penang (one battalion) and Malacca (one battalion).

Chan Cheng Yean, a volunteer with the Malacca Volunteer Corps recalled that he came to Singapore for training around 1940. “You have to go to the field, learn the location, how to attack the enemy. And then you learn how to be along the Singapore beaches and all, where they have pill boxes. Then we put up barbed wire when the enemy, when they tried to land, the barbed wire will stop them from entering… After the five days’ training we were sent back to Malacca.”30

Others joined Dalforce, a volunteer army formed by the local Chinese community to resist the Japanese invasion. It was named after its commander, Lieutenant Colonel John Dalley of the Federated Malay States Police Force.

Unfortunately, Dalforce volunteers lacked adequate training.31 “My impression of these people [being trained] is that they are brave but their training is far too short for them to know anything…… They were quite young. They consist of hawkers, shopkeepers and some of them could be working but they are not English educated,” said Jack Ng Kim Boon, who used to live in a kampong on Martin Road, near the Dalforce headquarters on Kim Yam Road.” He also recalled that they practised with shotguns rather than rifles.32

Destroying Traces of the Past

After the British surrender in February 1942, some people in Singapore destroyed traces of their past to avoid leaving behind a history of anti-Japanese activity.

Tan Wah Meng, a volunteer for the Medical Auxiliary Service, said people burned records to avoid them falling into the hands of the Japanese. His father, the chairman of the Bukit Timah and Jurong Chew Cheng Huay (Relief Fund) Committee, was one of those who got into trouble because of an incriminating photograph. “[I]t happened that somebody did not destroy a photograph of the committee. My father’s photograph [was] inside and the name inside. That’s why [the Japanese] looked [for] our family, you see. They got hold of that photograph.” Tan, his father and elder brother were later taken in for questioning by the Japanese. While Tan was released “one or two hours later”, his brother and father spent a week and a month locked up, respectively. In addition, his father suffered torture.33

Ang Seah San, the bookkeeper and sergeant of an ARP unit, said that he destroyed all documents relating to the ARP so as not to leave any evidence for the Japanese. “The wardens and I… we decided to destroy all records, logbooks, uniforms, helmets in order that we could deny of any connections with the previous government… Three days after our meeting, we were told that the British army surrendered, unconditionally to the enemy… We called the meeting because we got instruction from headquarters that we have got to be disbanded.… We advised all the other wardens that, your uniform, your uniform, your helmet all must be buried or burned away.”34

This destruction of records during wartime, both deliberate and accidental, underlines the importance of oral history. Through the memories of these survivors, captured on tape and now digitised for convenient access, we will be able to preserve vital aspects of Singapore’s past that would otherwise have no other trace.

Christabel Khoo is an Assistant Archivist with Records Management at the National Archives of Singapore.

Christabel Khoo is an Assistant Archivist with Records Management at the National Archives of Singapore.

Mark Wong is a Senior Specialist (Oral History) with the Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore, where he leads the oral history project on Singapore’s experiences with Covid-19. He is also Vice President of the International Oral History Association.

Mark Wong is a Senior Specialist (Oral History) with the Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore, where he leads the oral history project on Singapore’s experiences with Covid-19. He is also Vice President of the International Oral History Association.

NOTES

-

Lee Geok Boi, The Syonan Years: Singapore under Japanese Rule 1942–1945 (Singapore: National Archives of Singapore and Epigram Pte Ltd, 2005), 44. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING q940.53957 LEE-[WAR]) ↩

-

Toh Mah Keong, oral history interview by Lim How Seng, 27 December 1979, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc of 2 of 10, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000001), 18. ↩

-

Soh Guan Bee, oral history interview by Low Lay Leng, 17 August 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 10, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000310), 8–9. ↩

-

Tan Ban Cheng, oral history interview by Low Lay Leng, 25 January 1979, transcript and MP3 audio Reel/Disc 1 of 9, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000392), 7. ↩

-

Tan Guan Chuan, oral history interview by Low Lay Leng, 21 March 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 10, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000414), 12–13. ↩

-

Abdealli K Motiwalla, oral history interview by Chua Ser Koon, 19 August 1982, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 4, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000204), 1– 2. ↩

-

Abdealli K. Motiwalla, oral history interview, 19 August 1982, Reel/Disc 1 of 4, 3–4. ↩

-

“Singapore Will not be Evacuated in an Air Raid,” Straits Times, 8 May 1939, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Accommodation for Poorer Evacuees,” Straits Budget, 1 May 1941, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Why No Shelters Have Been Built In Singapore,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 13 September 1941, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee Tian Soo, oral history interview by Low Lay Leng, 23 April 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 7, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000265), 8. ↩

-

Tan Geok Koon, oral history interview by Claire Yeo, 11 August 2006, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 2, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003067), 3. ↩

-

Chu Shuen Choo, oral history interview by Low Lay Leng, 15 August 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 12, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000462), 9–10. ↩

-

Rajabali Jumabhoy, oral history interview by Lim How Seng, 15 July 1981, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 11 of 37, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000074), 72–73. ↩

-

Rajabali Jumabhoy, oral history interview, 15 July 1981, Reel/Disc 11 of 37, 72–73. ↩

-

Michael Mukunathan, “Rajabali Jumabhoy,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2016. ↩

-

Rajabali Jumabhoy, oral history interview, 15 July 1981, Reel/Disc 11 of 37, 73–74. ↩

-

Isa Ibrahim, oral history interview by Low Lay Leng, 6 January 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 11 of 28, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000242), 137. ↩

-

Lee, The Syonan Years, 44. ↩

-

Ang Seah San, oral history interview by Low Lay Leng, 24 March 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 7, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000419), 1–2. ↩

-

Ang Seah San, oral history interview, 24 March 1984, Reel/Disc 1 of 7, 2. ↩

-

Gay Wan Guay, oral history interview by Low Lay Leng, 17 April 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 22, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000374), 6–7. ↩

-

Lee Kip Lee, oral history interview by Cindy Chou, 13 July 1994, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 6, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001532), 3. ↩

-

Mani Letchumanan Masillamani, oral history interview by Jesley Chua Chee Huan, 23 April 2010, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 2 of 20, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003509), 41. ↩

-

Mani Letchumanan Masillamani, oral history interview, 23 April 2010, Reel/Disc 2 of 20, 43. ↩

-

“Scrap is Already Piling Up for ‘Salvage Week’,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 14 January 1941, 7 (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Soh Chuan Lam, oral history interview by Low Lay Leng, 5 September 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 8, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000304), 7. ↩

-

Alec Soong and Goh Lee Kim, “Singapore Volunteer Corps,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published October 2021. ↩

-

Chan Cheng Yean, oral history interview by Low Lay Leng, 8 March 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 4 of 10, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000248), 37–38. ↩

-

Kevin Blackburn and Daniel Chew Ju Ern, “Dalforce at the Fall of Singapore in 1942: An Overseas Chinese Heroic Legend,” Journal of Chinese Overseas 1, no. 2 (November 2005): 233–59, ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233511123_Dalforce_at_the_Fall_of_Singapore_in_1942_An_Overseas_Chinese_Heroic_Legend. ↩

-

Jack Ng Kim Boon, oral history interview by Low Lay Leng, 15 November 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 10, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000362), 2–3. ↩

-

Tan Wah Meng, oral history interview by Low Lay Leng, 17 August 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 4 of 17, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000306), 44. ↩

-

Ang Seah San, oral history interview, 24 March 1984, Reel/Disc 1 of 7, 3; Ang Seah San, oral history interview by Low Lay Leng, 24 March 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 2 of 7, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000419), 20–21. ↩