Belacan: Caviar? Or Vile and Disgusting?

Fermented shrimp is a staple in many cuisines of Southeast Asia, though it takes some getting used to.

By Toffa Abdul Wahed

While there is friendly rivalry between Singapore and Malaysia over who makes better food, for one notable family in Singapore, the best sambal belacan (a spicy condiment made from shrimp paste) indisputably comes from Malaysia, though only from a very special source.

In 2019, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong conveyed his thanks to the Malaysian queen for regularly sending over her sambal belacan to his family. “Thank you for your warmth and kindness, sending my father (and me) your special sambal belacan all these years!” he tweeted on 28 October 2019. “I hope you enjoy making it as much as we enjoy eating it!” A few days before, Raja Permaisuri Agong Tunku Hajah Azizah Aminah Maimunah Iskandariah had shared on her Instagram account a letter written in July 2009 by former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. He wrote that the six packets of sambal belacan she had given him were delicious. “I shared them with my two sons. They have all been consumed. It is the best chilli belacan we have tasted. Can my family have a few more?”1 Since then, she has been regularly sending her sambal belacan across the Causeway.

Sambal belacan is a regular accompaniment to rice in Malay, Eurasian and Peranakan meals. It is made by pounding toasted belacan with chillies and adding calamansi lime juice, salt and sugar to that mixture. While it is popular with many people, its key ingredient, belacan, has a somewhat malodourous reputation.

Hugh Clifford, who served as Governor of the Straits Settlements between 1927 and 1929, referred to belacan as “that evil-smelling condiment which [had] been so ludicrously misnamed the Malayan Caviare” in his 1897 account of the Malay Peninsula. He wrote that the coasts reeked of “rank odours” as a result of women villagers “labouring incessantly in drying and salting the fish which [had] been taken by the men, or pounding prawns into blâchan” throughout the fishing season. The stench was so strong that “all the violence of the fresh, strong, monsoon winds” would only “partially purge” the villages of it.2

In his book, A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands & Adjacent Countries (1856), John Crawfurd, the former Resident of Singapore, describes balachong (belacan) as:

“[A] condiment made of prawns, sardines, and other small fish, pounded and pickled. The proper Malay word is bâlachan [belacan], the Javanese trasi [terasi], and the Philippine bagon [bagoong]. This article is of universal use as a condiment, and one of the largest articles of native consumption throughout both the Malay and Philippine Archipelago. It is not confined, indeed, as a condiment to the Asiatic islanders, but is also largely used by the Birmese [Burmese], the Siamese, and Cochin-Chinese. It is, indeed, in great measure essentially the same article known to the Greeks and Romans under the name of garum, the produce of a Mediterranean fish.”3

Today, the Malay term belacan is commonly used in Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei and parts of Indonesia to refer typically to shrimp paste. In Thailand, Laos and Cambodia, it is called kapi, which is borrowed from the term ngapi (literally “pressed fish”) used in Myanmar, while it is referred to as mắm tôm or mắm ruốc in Vietnam.

Because it is rich in glutamates and nucleotides, belacan imparts savouriness to any dish, what is often described as “umami”. Other foods that are rich in umami include fish sauce, soya sauce, kimchi, mushroom, ripe tomato, anchovy and cheese.

Making Belacan

A 17th-century account gives a remarkably detailed description of making belacan. In 1688, the English privateer William Dampier encountered people making a paste of small fish and shrimps called balachaun during his visit to Tonkin (North Vietnam). He saw how this process produced nuke-mum or nước mắm (fish sauce) as well. His account, published in 1699, provides one of the earliest Western descriptions of making fish/shrimp paste:

“To make it, they throw the Mixture of Shrimps and small Fish into a sort of weak pickle made with Salt and Water, and put into a tight earthen Vessel or Jar. The Pickle being thus weak, it keeps not the Fish firm and hard, neither is it probably so designed, for the Fish are never gutted. Therefore in a short time they turn all into a mash in the Vessel; and when they have lain thus a good while, so that the Fish is reduced to a pap, they then draw off the liquor into fresh Jars, and preserve it for use. The masht Fish that remains behind is called Balachaun, and the liquor pour’d off is called Nuke-Mum.”4

While some versions of belacan use fish, it is held that the best ones are made from shrimp. In 1783, the Irish orientalist William Marsden, who worked for the East India Company in Bencoolen (now Bengkulu), wrote about the differences between black and red blachang in his book, The History of Sumatra:

“Blachang [belacan]… is a species of cavear, and is extremely offensive and disgusting to persons who are not accustomed to it, particularly the black kind, which is the most common. The best sort, or the red blachang, is made of the spawn of shrimps, or of the shrimps themselves, which they take about the mouths of rivers… The black sort, used by the lower class, is made of small fish, prepared in the same manner.”5

Fish and shrimp pastes have a very long history in Southeast Asia. Researchers believe that the techniques of fermenting fish most likely arose in areas on mainland Southeast Asia inhabited by communities who practised irrigated rice farming, had access to salt and faced seasonality in their fish stocks, which made preservation imperative. These techniques were then applied to the preservation of other raw ingredients such as shrimp and shellfish. They would later drift southwards throughout the rest of Southeast Asia.6 A Mon stone inscription from the first century CE provides the earliest record of the importance of ngapi in the Burmese diet. Ngapi manufacturers were also found in the list of occupations on a 12th-century stone inscription and a 15th-century marble monument from Myanmar.7 Inhabitants of the coastal cities of Pattani and Nakhon Si Thammarat (in present-day southern Thailand) used shrimp paste in their cooking as far back as the eighth century. These cities were then ruled by the Malay kingdom of Srivijaya from the island of Sumatra.8

“Evil”, “Nauseating”, “Noxious”

The smell associated with the making of belacan was noted by many observers. In the 1830s, the teacher, interpreter and writer Munshi Abdullah (Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir) visited a village market in Terengganu where he encountered what he perceived as a variety of “makanan yang busuk-busuk” (smelly, unwholesome foods), including tempoyak (fermented durian), different kinds of salted and fermented seafood products, petai (stink bean) and many types of sambal belacan. He criticised the lack of what he perceived as “makanan yang mulia” (wholesome foods) such as meat, ghee, eggs, butter and milk.9

In 1885, Scottish ornithologist Henry O. Forbes, wrote about his encounter with terasi and discovers, to his horror, that he had been eating it unknowingly for some time:

“Having got up rather late one Sunday morning… I was discomfited by the terrific and unwonted odour of decomposition. ‘My birds have begun to stink, confound it!’ I exclaimed to myself. Hastily fetching down the box in which they were stored, I minutely examined and sniffed over every skin… but all of them seemed in perfect condition. In the neighbouring jungle, though I diligently searched half the morning, I could find no dead carcase, and nothing in the ‘kitchen-midden,’… but at last in the kitchen itself I ran it to ground in a compact parcel done up in a banana leaf.

‘What on the face of creation is this?’ I said to the cook, touching it gingerly.

‘Oh! Master, that is trassi.’

‘Trassi? What is trassi, in the name of goodness!’

‘Good for eating, master; –in stew.’

‘Have I been eating it?’

‘Certainly, master; it is most excellent (enak sekali).’

‘You born fool! Do you wish to poison me and to die yourself?’

‘May I have a goitre (daik gondok), master, but it is excellent!’ he asseverated…

Notwithstanding these vehement assurances, I made it disappear in the depths of the jungle… I had then to learn that in every dish, native or European, that I had eaten since my arrival in the East, this Extract of Decomposition was mixed as a spice, and it would have been difficult to convince myself that I would come by-and-bye knowingly to eat it daily without the slightest abhorrence.10

Detailed written accounts like this provide insights into people’s attitudes towards belacan as well as the people who consume and produce it. A similarly degrading account came from the American naturalist William Hornaday. In his 1885 book, Two Years in the Jungle: The Experiences of a Hunter and Naturalist in India, Ceylon, the Malay Peninsula and Borneo, Hornaday remarked how the Chinese fishermen in a village at Sungei Bulu (most probably referring to Sungai Buloh), Selangor, “were engaged in catching prawns and making them up into a stinking paste called blachang”. He wrote: “Every house in the village is tumble-down, rickety and dirty beyond description, and the village smells even worse than it looks. The Chinamen live more like hogs than human beings; and, for my part, I would rather take up quarters in a respectable pig-sty than in such house as those are.”11

Enraged by a late-16th-century description of food written by Antonio de Morga (then lieutenant governor of the Philippines), José Rizal – the Filipino nationalist whose political writings inspired the revolution against the Spanish colonial government – wrote in 1890: “This is another preoccupation of the Spaniards who, like any other nation, treat food to which they are not accustomed or is unknown to them with disgust… This fish that Morga mentions, that cannot be good until it begins to rot, is bagoong and those who have eaten it and tasted it know that it neither is nor should be rotten.”12

Additionally, there were accounts about the supposed effects of belacan on health and sanitation leading to disease outbreaks. In Picturesque Burma, Past and Present (1897), British travel writer Alice Hart recounted that during a cholera epidemic in Yandoon, an English official imposed a ban on ngapi production because he was convinced that its stench exacerbated the situation. (At the time, some people still believed that diseases and epidemics were caused by miasmas or noxious vapours instead of pathogens or germs.) However, the order was so unpopular that it was eventually withdrawn, along with the officer involved.13

Hart also wrote that Catholic priests in Mandalay tested the theory that leprosy was caused by the consumption of decomposing fish. They conducted experiments in leper homes, which involved removing ngapi from the diet of the lepers in hopes that they might recover from the disease. The lepers, however, returned to their usual diet after a month as “their desire to taste ngapee again was greater than the hope of being cured”.14

The Belacan Trade

In 1856, with the passing of the Conservancy Act, trades carried out within the municipality that were defined as offensive and dangerous (including melting tallow, boiling offal or blood, sago manufacture, running brick, pottery or lime kilns, and storing hay, straw, wood or coal) had to be registered and licensed. The new law did not affect the belacan trade for four decades, but the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements amended it in 1896 to include the “drying and sorting of fish, and the drying or sorting or storing of blachan”. With that, the owner of a belacan factory or store would need to register for an annual licence as it was a “manufactory or place of business from which offensive or unwholesome smells arise”.15 There were reports in Singapore of people being fined for storing belacan for trade in buildings without a licence within the municipality. For instance, in December 1897, a Chinese man named Lee Pow was fined 50 dollars for storing 280 bags of belacan in a house on Cecil Street without a licence.16

Although the belacan industry in Singapore and Malaya might not have been as economically important as the rubber, tin or even dried and salted fish trades, it was still significant. Belacan was a cheap provision for tin miners living in the major tin-mining areas such as Perak, Selangor and Sungei Ujong (now known as Seremban). They ate it with rice to make the meal more flavourful. The traveller and orientalist Thomas J. Newbold wrote in 1839 that Melaka traded items like belacan, salted fish, opium, specie, fish roe and tobacco for rice, tin, gold dust, ivory and ebony with states located in the interior. He also noted that Melaka exported a “considerable quantity of blachang” along with other commodities like hides, pepper, bricks and tiles as well as some ebony and ivory to Singapore.17

In his 1923 report, marine biologist David G. Stead states that belacan was “of very large importance” in the fish trade in many parts of Malaya. Stead had travelled along the Malayan coasts in the early 1920s to survey local fisheries and come up with recommendations for developing the industry. He explained that the fisheries in Province Wellesley (now known as Seberang Perai, a city in the state of Penang) and along the coasts of Perak and Selangor produced large quantities of belacan, whereas the growing fishery in Johor’s Kukup produced considerable amounts. He highlighted Bagan Luar, a fishing village located across from Penang Island, as the most important place in Malaya in terms of belacan manufacture and export. The other major site along the Strait of Malacca was Bagan Si Api Api.18 This town, which developed in the rich estuary where Sumatra’s Rokan River meets the Strait of Malacca, was home to an industrial fishery that produced a yearly average of nearly 30 million kilograms of fish and belacan between 1898 and 1928.19

Belacan in Singapore

Singapore played a vital role regionally as an entrepôt for belacan as well as other products like canned and salted fish.20 Singapore was the principal importer and exporter of belacan for the Straits Settlements. The bulk of the exports went to Java. Between 1920 and 1927, for instance, the Straits Settlements exported almost 16,000 tons of belacan to Java, amounting to almost $3,100,000. The next two largest amounts exported from the Straits Settlements via Singapore were to British India and Burma (about 8,400 tons), and Siam (about 6,700 tons) during the same period.21 Even after the dissolution of the Straits Settlements in 1946, Singapore continued its role as a major distribution centre for belacan; this time, it was for the Federation of Malaya.22

In 1900, there were 36 registered belacan factories within Singapore’s Municipal Area. The number, however, decreased over time; by 1939, only three were left.23 Maps produced between the 1930s and 1950s indicate three belacan factories at the Kallang Basin, with two located right by the Kallang River. Parts of these buildings appear to be submerged in water, suggesting that they were built on stilts. Each building also had an attached large wooden platform, most likely used for laying out and drying the shrimp paste.24

According to the Annual Report of the Fisheries Department for 1950 and 1951, the production of belacan in Singapore was negligible and much of the supply was imported from Malaya. The Federation of Malaya provided 600 tons of belacan for consumption within Singapore in 1950 alone.25 Even so, Tampines had a thriving belacan industry in the early 1950s that catered to local demand. Sungai Tampines and Sungai Api Api, two rivers that flow through Tampines and Pasir Ris and into the Strait of Johor, were rich in fish and udang geragau (small shrimps used to make belacan) at high tide.26

Lubuk Gantang, the confluence of three Sungai Tampines tributaries, was once abundant with these shrimps. This was a popular spot for villagers looking to catch and sell the shrimps fresh or to make them into belacan. However, this place no longer exists due to land reclamation. Over time, the belacan industry in Tampines declined not only due to reclamation, but also because people moved away from the area. By 1986, more than half of the villagers had moved into flats in new housing estates like Bedok, Hougang and Tampines.27

The udang geragau were caught using sondong (push-net), also known as selandang and sungkor.28 These used to be a familiar sight in nearshore areas like Siglap, Changi, Tampines and Seletar. Part-time or subsistence fishermen, including small boys, would typically use a smaller type of push-net. The Fisheries Survey Report (1959) describes the sondong as a net that is carried between two light wooden poles approximately five metres in length. “Shoes” made out of hardwood or coconut husk are attached to one end of the poles. The fisherman operates the sondong by standing between the poles and lowering the net into the water until the “shoes” reach the bottom. He then pushes it slowly along the seabed and lifts it after some time. With a few shakes, the catch goes into the bag-like end of the net. Longer poles were used by some fishermen who operated the net from boats in deep water.29

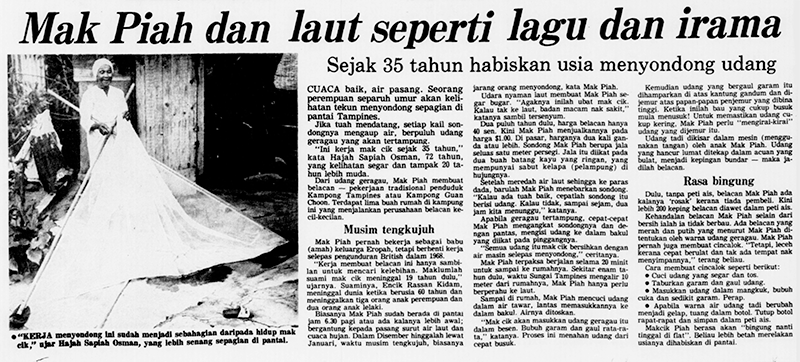

Despite ongoing urban redevelopment and reclamation, there was still a cottage industry of five households producing belacan in Kampong Tampines in the 1980s. In an interview with the Berita Harian newspaper in 1986, village resident 72-year-old Sapiah Osman, better known as Mak Piah, said that she had been catching shrimps since she was 35.

The widow started making belacan as part-time work to feed her family. She was usually at the shore by 6.30 am. Depending on the tide and weather, she might even be there earlier. On a good day, it did not take long for her sondong to be filled with shrimps. On other days, she would have to wait one to two hours to get a good catch.30 Like her, other fisherfolk made and sold belacan as a means to earn extra income for their families. Mak Piah sold her belacan for $1.

While belacan production still endures in other parts of Southeast Asia today, scenes of people catching udang geragau with their sondong and making belacan are long gone from Singapore. The shores are now void of the smell of drying fish and belacan, although one can still catch the aromatic whiff of belacan being toasted from homes and eateries.

In 1973, a belacan scandal rocked kitchens in Malaysia and Singapore. The authorities found belacan from Penang adulterated with a poisonous and carcinogenic dye, the prohibited substance Rhodamine B, which was used to give it an appealing reddish hue.

This may have motivated some people to make belacan at home, hence this recipe by a Mrs Tan Bee Neo that was published in the New Nation newspaper a few years later.

Ingredients:

Use a Chinese tea cup as a measure.

10 heaped cups of fresh shrimp (udang geragau) and a little less than one cup of salt.

Method:

1. Do not wash the shrimps unless it is with fresh seawater. Sort through the shrimp to remove small fish, seaweed or other foreign matter.

2. Drain the shrimp and mix thoroughly with salt. Spread evenly on a large tray and dry in the sun for one day, or till damp-dry.

3. Pound the shrimp. The shrimps will still be moist and will easily bind into a paste. Shape into small cakes, the size of an egg and flatten.

4. Dry these in the sun for at least two days. Pound once more to get a finer paste. Re-shape into cakes and dry in the sun for two more days or more depending on the sunshine.

5. Check the texture for smoothness, you would probably have to re-pound the belacan.

6. When satisfied that the belacan is suitably fine, that is, the shrimps are indistinguishable from each other, shape the paste into cakes and leave once more in the sun for at least four days until the cakes are quite dry.

7. Belacan keeps well indefinitely, but be sure to dry the cakes in the sun every now and then to remove moisture that may have collected in storage.

RECIPE FOR SAMBAL BELACAN

This recipe is taken from Rita Zahara’s cookbook, Malay Heritage Cooking (2012).

Ingredients:

10g belacan

7 red chillies

3 red bird’s-eye chillies

Salt to taste

Sugar to taste

2 limes, juice extracted, zest thinly sliced

Method:

1. Heat a small frying pan and dry-fry belacan for a few minutes until fragrant.

2. Using a mortar and pestle, pound belacan with chillies until well combined. Remove to small bowl.

3. Season with salt and sugar to taste. Add freshly squeezed lime juice and lime zest.

Sambal belacan is a popular condiment made of chillies, belacan and lime juice. It is a must-have accompaniment to Malay, Peranakan and Eurasian dishes. Courtesy of Mrs Tan Geok Lin.

REFERENCES

“Making Belacan Is Hard Work,” New Nation, 10 August 1978, 12. (From NewspaperSG)

Rita Zahara, Malay Heritage Cooking (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Cuisine, 2012), 31. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 641.595957 RIT)

Sa’adon Ismail, “Belacan Yang Dijual di Sini Ada Ramuan Rhodamine B,” Berita Harian, 9 August 1973, 12. (From NewspaperSG)

Salim Osman, “‘Racun Dlm Belacan’ Disiasat,” Berita Harian, 3 July 1973, 1. (From NewspaperSG)

Salma Semono, “Penggunaan Belacan Kurang Sejak Julai Lalu,” Berita Harian, 15 March 1974, 3. (From NewspaperSG)

Toffa Abdul Wahed is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection.

Toffa Abdul Wahed is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection.NOTES

-

“PM Lee Expresses Appreciation to Malaysia’s Queen for ‘Royal’ Sambal Belacan,” Today, 29 October 2019, https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/pm-lee-expresses-appreciation-permaisuri-agong-royal-sambal-belacan. ↩

-

Hugh Clifford, In Court & Kampong: Being Tales & Sketches of Native Life in the Malay Peninsula (London: Grant Richards, 1897), 137. (From BookSG) ↩

-

John Crawfurd, A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands & Adjacent Countries (London: Bradbury & Evans, 1856), 27. (From BookSG). Also see Gracie Lee, “Crawfurd on Southeast Asia,” BiblioAsia 11, no. 4 (January–March 2016): 16 –17. For more information on garum, see Sally Grainger, The Story of Garum: Fermented Fish Sauce and Salted Fish in the Ancient World (Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 2021). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 338.4766494 GRA) ↩

-

William Dampier, Voyages and Descriptions: Vol.II. In Three Parts, Viz. I. A Supplement of the Voyage Round the World, … 2. Two Voyages to Campeachy; … 3. A Discourse of Trade-winds, Breezes, Storms, … By Capt. William Dampier. Illustrated with Particular Maps and Draughts. To Which Is Added, a General Index to Both Volumes (London: Printed for James Knapton, 1699), 28, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/voyagesdescripti00damp/page/n7/mode/2up. ↩

-

William Marsden, The History of Sumatra: Containing an Account of the Government, Laws, Customs, and Manners of the Native Inhabitants, with a Description of the Natural Production, and a Relation of the Ancient Political State of that Island (London: William Marsden, 1783), 57–58. (From BookSG) ↩

-

Kenneth Ruddle and Naomichi Ishige, “On the Origins, Diffusion and Cultural Context of Fermented Fish Products in Southeast Asia,” in Globalization, Food and Social Identities in the Asia-Pacific Region, reissued edition, ed. James Farrer (Tokyo: Sophia University Institute of Comparative Culture, 2021), 28–45, https://www.academia.edu/391558/On_the_Origins_Diffusion_and_Cultural_Context_of_Fermented_Fish_Products_in_Southeast_Asia. Fermented shrimp paste is also made and consumed in countries outside of Southeast Asia like Korea, China and Bangladesh. ↩

-

Myo Thant Tyn, “Industrialization of Myanmar Fish Paste and Sauce Fermentation” in Industrialization of Indigenous Fermented Foods, 2nd edition, ed. Keith Steinkraus (New York; Basel: Marcel Denker, Inc., 2004), 739, https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203022047. ↩

-

Su-Mei Yu, “A Lamentation for Shrimp Paste,” Gastronomica 9, no. 3 (2009), https://gastronomica.org/2009/08/05/a-lamentation-for-shrimp-paste/. ↩

-

Amin Sweeney, Karya Lengkap Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir Munsyi, Jilid 1 (Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia, 2005), 134. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Malay RSING 959.5 KAR) ↩

-

Henry O. Forbes, A Naturalist’s Wanderings in the Eastern Archipelago, a Narrative of Travel and Exploration from 1878 to 1883 (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1885), 60–61. (From BookSG) ↩

-

William T. Hornaday, Two Years in the Jungle: The Experiences of a Hunter and Naturalist in India, Ceylon, the Malay Peninsula and Borneo with Maps and Illustrations (London: K. Paul, Trench, 1885), 304. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 910.4 HOR) ↩

-

Ambeth R. Ocampo, “Rizal’s Morga and Views of Philippine History,” Philippine Studies 46, no. 2 (1998): 184. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Alice Hart, Picturesque Burma, Past and Present (London: J.M. Dent and Co, 1897), 188. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.1 HAR) ↩

-

Hart, Picturesque Burma, Past and Present, 188. ↩

-

“Government Notification,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 23 August 1856, 1; “Legislative Council,” Straits Times, 31 July 1896, 3. (From NewspaperSG). Even though the section pertaining to belacan was only passed in 1896, belacan businesses had to register and pay for licences before that. See “Page 3 Advertisements Column 2,” Daily Advertiser, 14 January 1891, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Wednesday, 8th December,” Straits Budget, 14 December 1897, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Thomas John Newbold, Political and Statistical Account of the British Settlements in the Straits of Malacca, viz. Pinang, Malacca, and Singapore: With a History of the Malayan States on the Peninsula of Malacca, vol. 1. (London: John Murray, 1839), 145, 150. (From BookSG) ↩

-

David G. Stead, General Report Upon the Fisheries of British Malaya With Recommendations for Future Development (Sydney, New South Wales: Alfred James Kent, Government Printer, 1923), 253. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 639.209595 STE; microfilm no. NL26000) ↩

-

Anthony Medrano, “The Edible Tide: How Estuaries and Migrants Transformed the Straits of Melaka, 1870–1940,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 51, issue 4 (December 2020): 585–86. (From ProQuest via NLB’s eResources website). For more discussion on Bagan Si Api Api, see John G. Butcher, “The Salt Farm and the Fishing Industry of Bagan Si Api Api,” Indonesia no. 62 (October 1996), 90–121. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

T.W. Burdon, The Fishing Industry of Singapore (Singapore: Donald Moore, 1955), 46. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 639.2095957 BUR) ↩

-

Toffa Abdul Wahed, “Caviar of the East: Shrimp Paste in the Food and Foodways of Southeast Asia” (BA Thesis, National University of Singapore, 2013), 47–49, https://scholarbank.nus.edu.sg/handle/10635/191487. ↩

-

T.W. Burdon, Annual Report of the Fisheries Department, 1950 (Singapore: Fisheries Department, 1951), 58; T.W. Burdon, Annual Report of the Fisheries Department, 1951 (Singapore: Fisheries Department, 1952), 69. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 639.2 SIN); Burdon, Fishing Industry of Singapore, 48. ↩

-

Toffa Abdul Wahed, “Caviar of the East,” 21. ↩

-

For example, Survey Department, Singapore, Singapore. Kalang Mukim (Kallang Mukim), and Town Subdivision Number XVII, 1937. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. SP006035). [Note: The map was originally produced in 1932. Markings in pencil and red ink were added in later years and the last amendments were made in 1937.] ↩

-

Burdon, Annual Report of the Fisheries Department, 1950, 58; Burdon, Annual Report of the Fisheries Department, 1951, 69. ↩

-

Udang geragau is also used to make cincalok, another fermented shrimp product. A Dictionary of the Economic Products of the Malay Peninsula, first published in 1935, mentions udang geragau, udang rebon, udang pepai and sanggugu (also spelt as senggugu) as the recorded Malay names for Acetes, a genus of small shrimp that resembles krill. The species Acetes erythraeus Nobili was one of those used in belacan production in Singapore. See I.H. Burkill, A Dictionary of the Economic Products of the Malay Peninsula, vol. 1 (Kuala Lumpur: Published on Behalf of the Governments of Malaysia and Singapore by the Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives, 1966), 684. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 634.909595 BUR) ↩

-

“Kisah di Sebalik Nama2 Menarik di Kg Elias,” Berita Harian, 9 July 1986, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ali Salim, Kampong Keranji 1948–1973: Sebuah Memoir (Singapore: IQrak Publication & Distribution, 2021), 46. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Malay RSING 959.57 ALI-[HIS]); “Jaminan Menteri Abd. Aziz Ishak,” Berita Harian, 4 October 1960, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

T.W. Burdon, Fisheries Survey Report, No. 2: The Fishing Gear of the State of Singapore (Singapore: Printed at the Government Printing Office, 1959), 103–104, 145. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 639.2095957 BUR-[JSB]) ↩

-

“Mak Piah dan Laut Seperti Lagu dan Irama,” Berita Harian, 9 July 1986, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩