S'pore’s Armenian Church Survived Close to 180 Years, S'pore’s Original Armenian Community Did Not

Never large, Singapore’s Persian Armenian community barely survived the war. Then came the demographic collapse.

By Alvin Tan

The Straits Times. The Raffles Hotel. The Vanda Miss Joaquim. These quintessentially Singaporean icons are associated with a community here that somewhat remarkably never totalled more than 100 at any given time in Singapore – the Armenians.1

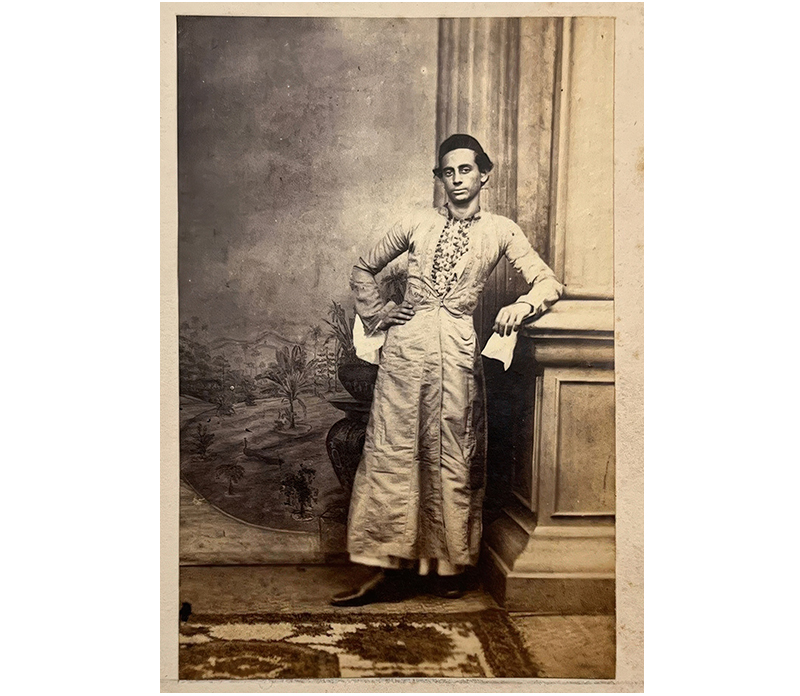

To be clear though, while usually referred to as Armenians, the people who arrived in Singapore in the early decades of the 19th century did not come directly from Armenia, a landlocked country bordered by Turkey, Georgia, Azerbaijan and Iran. The early migrants were, instead, descendants of a population that had been resettled from the Armenian city of Julfa to Persia (present-day Iran) in the 17th century.2

These Persian Armenians later settled in India, and then migrated to Java and the Malay Peninsula. Very soon after the British East India Company established a trading post in Singapore in 1819, the Armenians from nearby places like Penang and Melaka began arriving. By 1821, three Armenians – Aristarchus Sarkies, Arratoon Sarkies of Melaka, and another – had set up firms in Singapore.3

Once in Singapore, the Armenians quickly established various businesses and made important contributions to society. Catchick Moses bought printing equipment from a fellow Armenian merchant who had gone bankrupt, and launched the Straits Times and Singapore Journal of Commerce with Robert Carr Woods, an English journalist from Bombay, in July 1845.4

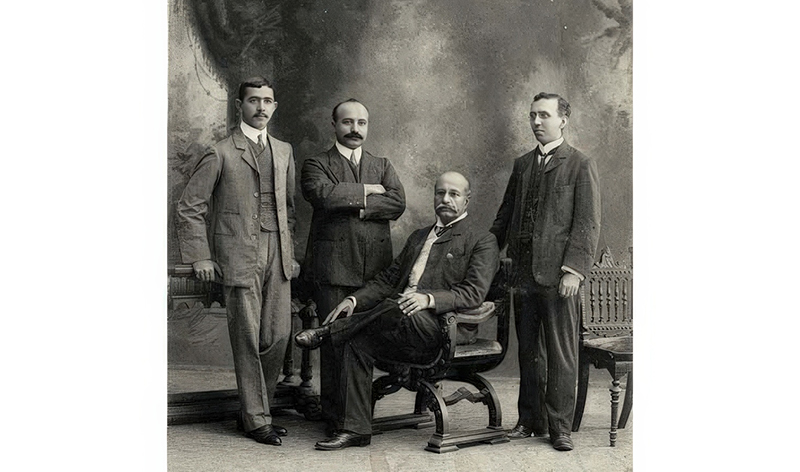

In 1887, the Sarkies brothers, Martin and Tigran, leased an existing building and turned it into the Raffles Hotel, after previously establishing the Eastern Hotel and Oriental Hotel in Penang.5 Merchant and trader Parsick Joaquim came from Madras around 1840. His daughter Agnes Joaquim cultivated the hybrid orchid Vanda Miss Joaquim and details about the hybrid were written up by H.N. Ridley, director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens, in 1893.6 (The orchid was chosen as Singapore’s national flower in 1981.)

Founding of the Armenian Church

While the Armenians were certainly astute business people, they were also very religious. Christianity had been declared Armenia’s state religion in 301 and being able to worship regularly was important to the Persian Armenians in Singapore.

When they first came here, the small community was served by Reverend Eleazor Ingergolie, who was based in Penang but travelled down to Singapore to conduct services. However, the Armenians here eventually wanted their own resident priest and in 1825, they wrote to the Archbishop in Persia asking for a priest to be posted here.7

Two years later, the Reverend Gregory ter Johannes arrived and the first services were held in a backroom at John Little & Co. in Raffles Place. The services were subsequently held in a small, rented room in “Merchant’s Square”. The cost of supporting the priest, renting the premises and staff wages amounted to $63 a month.8

Eventually, though, the community wanted their own dedicated building. In 1833, they wrote to Samuel Bonham, the Resident Councillor in Singapore, for the piece of land “lying at the Botanical Gardens facing the public road called ‘the Hill Street’”. Approval was given in July 1834 and George D. Coleman was commissioned to design the building. The foundation stone was laid in January 1835 by the Very Reverend Thomas Gregorian, who had come from Persia for the event, and the local priest Reverend Johannes Catchick. The cost of the building came up to $5,058.30 (of which Coleman received $400 as architect and engineer.)9

Finally, on 26 March 1836, the Armenian Apostolic Church of St Gregory the Illuminator was consecrated by Reverend Johannes.10 In his sermon that followed the service, he told the congregation: “It now affords me uncommon pleasure to see you, brethren, assembled this morning under this roof, with joy in your hearts, because the house of God is much more fitting to worship in than our places of abode; there we enjoy bodily rest; here spiritual; as our Saviour observed – The soul is more worth than the body.”11

Galvanising the Community

The church was an important part of Armenian life in Singapore. It was where the Sunday service – known as the Divine Liturgy – was celebrated, where major feast days were observed, and where life events such as baptisms and weddings were held.

The church was also important for fostering a sense of community. Unlike the other immigrants such as the Chinese and the Indians, the Armenians tended to come to Singapore in family groups. Weekly church services would have allowed the men, their wives and their children to meet others of the same cultural and religious background on a regular basis. Friendships were formed, children grew up together and business opportunities were discussed. Run and maintained by the community and volunteers, the church was where community ties were strengthened.

Historian Nadia Wright noted that various members of the congregation raised money to pay for modifications to the roof and dome in the 1840s and 1850s: “Over the years, generous individuals further contributed to improvements and additions. For example, in 1861, Peter Seth donated the bell in the steeple, although this was not hung until the 1880s. In that same decade, Catchick Moses paid for the back porch and a new fence around the compound.”12

However, the original dome and turret were deemed unsafe, and both were replaced by a square turret by 1847. The problem persisted, and around 1853, the turret was removed and the pitched roof replaced with a flat one.13

With the generous support of Seth Paul, the church and parsonage became the first church in Singapore to enjoy the comfort and convenience of electricity on 18 January 1909.14

Of course, the volunteers did more than build up the physical infrastructure. They were involved in other ways as well. Among her many talents, Agnes Joaquim was also skilled in needlework and she embroidered a beautiful altar cloth for the church.15

The tight-knit Armenian community also organised non-religious activities. The tragic events of the Armenian genocide in 1915 galvanised the community. Church trustees H.S. Arathoon and M.C. Johannes launched an appeal for funds on 16 October 1915 to relieve the plight of the Armenians. (They themselves donated $500 each.)16 Services were held regularly until the resident priest left Singapore in 1938.

Dwindling Population

The onset of World War II and the Japanese Occupation accelerated the decline of the community. During the Occupation, 19 Armenians who were British subjects were incarcerated. Civilians were interned in Sime Road Camp, while those who served in the Singapore Volunteer Corps or Local Defence Volunteers were interned in Changi Prison.17

The church itself took enemy fire during the war as its grounds had been requisitioned by the British Army. When the Japanese started dropping bombs on Singapore, some fell near the church, which loosened masonry and timber while the roof of the parsonage caved in. Subsequently, the building was looted by the Japanese who removed the crystal chandeliers and carpets from the church, and furniture and paintings from the parsonage; these were never replaced.18 During the Occupation years, the church was used by other Christian denominations – the Mar Thoma Syrian Church and Geylang Methodist Church – for their Sunday services.19

After the war, the population of Armenians in Singapore continued to fall as a result of emigration and as people died. In the 1947 census, which was the last to report the Armenians as a discrete category, there were just 62 of them.20 In December 1949, Arshak C. Galstaun, a trustee for the church, told the Straits Times that there were only about 40 Armenians left in the community.21

Because of the small numbers, the community found it hard to maintain the church. Four years after the end of the war, the Straits Times described the church as being “in a worse way than any other house of God in Singapore. Plaster is crackling and peeling from the walls, roof timbers are falling, white ants have made such inroads on the gilded centrepiece of the ceiling that you can break off chunks, like stale bread”.22

Official compensation for war damage was paltry and church funds had to be used for repairs. Eventually, the parsonage was repaired with personal contributions from Walter, Robert and Looleen Martin.23

The small numbers also made it harder to keep regular church services going. In 1953, the Straits Budget noted: “Walking into the Armenian Church of St Gregory, the Illuminator in Coleman Street you will find every Sunday that the altar candles are lighted and the liturgy stands open. But there is no service. At nine every morning, the Churchwarden, ex-Japanese P.O.W. Mr Joannes, reads players [sic] to the steadfast remanant [sic] of the faithful.”24

The first Divine Liturgy to be served after the war was on 9 May 1954. It was an important moment for the Armenian community because the last time the Liturgy had been celebrated in Singapore was some 16 years earlier. “Armenians have bought a new altar cloth (the one old having rotted away). They have scrubbed the floor and whitewashed the walls,” reported the Straits Times. “The church is fragrant with fresh flowers, candles are lighted and a choir of seven have been practising hymns unsung here since 1938.”25 This, however, was not the start of regular services as the priest was a visiting clergyman.

Three years later, in May 1957, the Straits Times reported that the first Divine Liturgy in 30 years to be celebrated by a bishop would take place. Monsignor Tereniz Poladian flew in from Beirut to do so. “On Sunday, the Colony’s community of about 70 will attend a long-awaited pontifical service. The church which has been renovated at the cost of about $20,000, has just been completely refurnished. A choir of eight has been practising for the past two weeks for the big occasion.”26

Preserving the Church

Although the Armenian community in Singapore was small and the church suffered because of the lack of funds to maintain it, the church, to the Armenians, was and still is a sacred space. But from the 1950s, there was a growing sense in Singapore that the church building was not just a sacred space, but an important part of Singapore’s history.

In May 1954, a local group began to advocate publicly for its conservation. The Straits Times reported that the “Friends of Singapore, a cultural society, plans to rescue the old Armenian Church in Coleman Street because of its historical interest. It also plans to save the house of its architect Mr. Coleman… the society will make local Armenians an offer of help in the rehabilitation of the building”.27

The church was indeed fixed up, though apparently without using funds from outside. This meant that it was done on a relatively small budget. The results of the restoration did not please everyone. In a commentary in April 1956, Straits Times contributor Stanley Street criticised the community’s restoration efforts that had left the church, in his opinion, unrecognisable.

Street wrote: “Had they possessed the means to carry out the long-delayed repairs while still preserving the charm and irreplaceable craftsmanship that has been lost, be sure they would have done so. But the community wished to restore their church from the slender funds at their disposal. Offer from other sources to help in this endeavour were declined, and for that we must respect the Singapore community of perhaps the oldest church in Christendom.”28

In response, Arshak C. Galstaun, the church trustee and warden, wrote that his “first reactions to the article… were violent and I have, therefore, waited a few days to simmer down and to consult my church board”. He noted that the parsonage had been completely repaired through the generosity of the Armenian Martin family and that the church spent several thousand dollars about five years ago to ensure it was structurally safe. He ended his response with a strongly worded reminder to the writer. “I would impress upon Stanley Street that the Armenian Church is private and sacred. We desire to be left alone to manage our own affairs as we think fit.”29

Yet, this view that only Armenians had a say over the church was increasingly untenable as the 1960s unfolded. In addition to being an Armenian property and a consecrated space, the state was beginning to recognise it as a heritage building with great historical value, especially to a new nation.

In 1969, it was reported that the government was looking into setting up a national monument trust to preserve buildings of historical importance and the Armenian church was on that list.30 In 1970, the Preservation of Monuments Act was passed, and in July 1973 the Preservation of Monuments Board gazetted the church as a national monument alongside seven others.31

The church trustees now had to balance this status with that of a consecrated space for the practice of Armenian Christianity. It was not easy, especially since the church in the 1970s and 1980s was thinly used as the population continued to dwindle. The Straits Times reported in December 1978 that “the Armenian community now barely raises the required quorum of 12 at the church’s annual general meeting to keep the church going as a registered society”.32

This tension came into sharp relief following a piece written by Australian architect Peter Keys in the Straits Times. After a visit to the church in September 1981, he had obviously been enamoured with the buildings and the grounds, and suggested ways in which they could be used.

The grounds, he wrote, “could be opened more to the public, mainly for passive recreational uses, although the odd fete-like occurrence would not be objectionable”. He also suggested that the church itself could be used for a variety of purposes. It could be “one of the central spaces for people to congregate when exploring their city, with a large model and photographs” and for “small and intimate performances of music and drama”. The building, he noted, is “too entrenched in our history for its preservation and conservation to depend on a few funds and the love and care of a few dedicated Armenians”. “The buildings and their grounds are for us all to enjoy and take pleasure in. As such, their use should be carefully considered,” he added.33

Church trustee Art Baghramian pushed back against these well-meaning suggestions. “First, I would like to point out that the Armenian Church is and has always been supported and maintained solely by private sources,” he wrote. “Therefore, the use of the church and its grounds is not open to public debate. Second, and more important, is the fact that though religious services are not held at the church on a regular basis, it maintains a sacred and holy place. As such, it is not maintained for profane or secular use.”34

In the quest to maintain the church as a sacred space and also allow it to be enjoyed as part of Singapore’s heritage, the church accepted a proposal from the Singapore Tourist Promotion Board (now Singapore Tourism Board) in 1985 to allow the premises to be used as a wedding venue for Japanese tourists.

“Wedding bells will ring again at the Armenian church next month when visiting Japanese couples walk down the aisle as part of a newly launched holiday package for Japanese honeymooners,” the Straits Times reported. “The couples will go through a simple ceremony at Singapore’s oldest Christian church, which is celebrating its 150th anniversary this year.”35 At that point, the church served about 20 Armenians still living in Singapore.

This proved to be a short-lived engagement though. Only one such wedding eventually took place before things went awry. “Church elders objected on grounds that marriage is a serious affair and should not be treated lightly.”36 Although the Straits Times did not elaborate, it did report that the plan had been to allow Japanese newly-weds to tie the knot again in “mock church weddings”. It was a popular custom among Japanese honeymooners to go abroad to get “married” and have photos taken in a picturesque church, even though they had already undergone a traditional wedding back in Japan.

The Last of the Armenians

By the late 1980s, the Persian Armenian community had shrunk to about a dozen people. A 1988 report by the Straits Times said that there were just four “pure Armenians”: Mackertich Zachariah Martin, Rita Poon, Mary Christopher and Helen Metes. (It is not entirely clear what the newspaper meant by the term “pure Armenians”.) At 39, Mrs Rita Poon was the youngest of the four. She had been born in Iran but married a Chinese Singaporean. In addition to the four, the paper wrote that there were about a half-dozen half-Armenians and about 20 or 30 expatriates.37

Helen Catchatoor Metes, the last Persian Armenian in Singapore, died in 2007. After that, what was left comprised a handful of people who only had a distant Persian Armenian connection, perhaps a last name, but who were no longer Armenian Orthodox, and who no longer spoke the language.38

Among them was Loretta Sarkies, who was profiled in the Straits Times in September 2015. Then 74, she was the oldest daughter of James Arathoon Sarkies, who ran the Happy World Cabaret in the 1940s, and Mae Didier. Her granduncle was Tigran Sarkies, one of the four brothers who set up the Raffles Hotel. One of Loretta’s daughters, Debra, eventually decided to change her last name from Aroozoo (Loretta had married Dutch-Eurasian civil servant Simon Aroozoo) to Sarkies at the suggestion of a visiting Armenian priest in an effort to keep the Sarkies name alive.39

In 1994, the church embarked on a conservation project. The roof was waterproofed, the electrical system upgraded and the termite-infested windows replaced. The walls were also replastered and treated to prevent dampness. The building was restored just in time for a service by visiting Armenian Orthodox Bishop, Oshagan Choloyan.40

The restoration of the church came just in time because even though the number of Persian Armenians was getting smaller, the community of Armenian expatriates was growing. There were Americans and Australians of Armenian descent in Singapore. There were also Armenians from Armenia, especially after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. (Armenia had come under Soviet domination after World War II.)

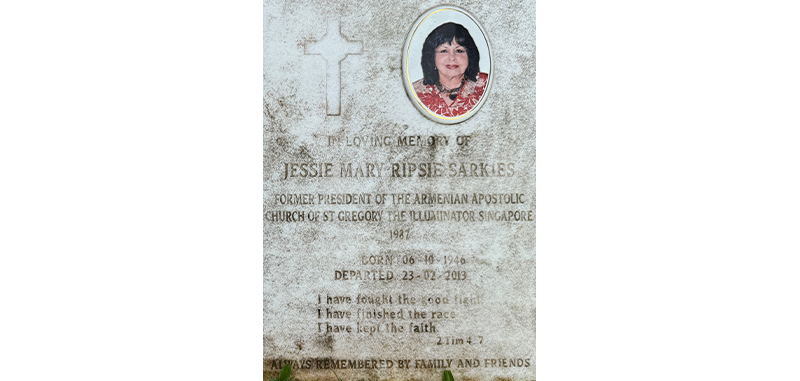

While this influx boosted numbers, the newcomers were culturally different from long-time Singapore Armenians. For one, there was the issue of language. The newcomers, especially those from Armenia, could speak Armenian while the descendants of the Persian Armenians in Singapore could not. In an oral history interview, Jessie Sarkies, the sister of Loretta Sarkies, described how she felt left out at an event because everyone was speaking Armenian and she couldn’t:

“I would say the Armenian people are nice, but they are very proud of whom they are. They are, on Saturday I found out, when I was told that I have to know to speak Armenian. Yah, and it’s like there’s distinction, and then I felt oh, I was so left out after that. Because I couldn’t mingle with everyone, because everyone down there all talks Armenian… So there’s this distinction between me and them, because they all talk Armenian. I felt very down.”41

The newcomers did rejuvenate the community though. In 2010, violinist Ani Umedyan and her musician husband Gevorg Sargsyan, vocalist Gayane Vardanyan and pianist Naira Mkhitaryan formed the Armenian Heritage Ensemble to bring the Armenian culture to the people in Singapore. The ensemble plays music by Armenian composers in the church four times a year.42 In 2011, some 60 Armenians gathered to commemorate the Armenian genocide and also to celebrate Easter.43

At one point, according to a 2017 news report, a priest from Myanmar would come to Singapore five to six times a year to celebrate the Divine Liturgy here. In that report, Umedyan, who is also a regular church volunteer, said that when she first started worshipping at the church, there were only about 20 or so people. “Now that more expats have come, there are more people and we are happy to see the church crowded with about 40 to 50 people at each service.”44

Another boost to the community and its profile came in May 2018 when the $1.2 million Armenian Heritage Gallery, housed in the historic parsonage building, opened.45

Today, there are about 100 people in the community, a quarter of whom are from Armenia while the rest are from the diaspora. While small, the community is determined to keep its culture and traditions alive.

On 27 March 2022, the Divine Liturgy resumed for the first time following Covid-19 restrictions on gatherings.46 The Liturgy was celebrated most recently on 9 June 2024 by Archbishop Haigazoun Najarian. The Ambassador of Armenia to Singapore – Serob Bejanyan, who is based in Jakarta – attended the service.

According to church trustee Pierre Hennes, the church is now committed to the construction of a community reception hall next to the parsonage. “The hall will serve as a unique venue for community gatherings, wedding receptions, and other cultural outreach programmes hosted by the church and community,” he said. Work has already begun on building this hall.

Hennes added that he saw the role of the church as being a “beacon for all Armenians and Singaporeans – whether visitors or residents – that serves as a platform to expose, maintain and advance the Armenian religion, culture and heritage”. Not just a religious centre, the church was also a physical space for “connecting with each other and reinforcing the culture, highlighting our contributions to Singapore’s past and present, and to be a part of the fabric of Singapore’s future”.47

Note: This article has been updated since it was first published. Corrections and clarifications have been made.

Alvin Tan is an independent researcher and writer focusing on Singapore history, heritage and society. He is the author of Singapore: A Very Short History – From Temasek to Tomorrow (Talisman Publishing, 2nd edition, 2022) and the editor of Singapore at Random: Magic, Myths and Milestones (Talisman Publishing, 2021).

Notes

-

Sona Avagyan, “Nadia Wright: Making Sense of Historical Mysteries Is Fascinating,” Hetq, 6 December 2010, https://hetq.am/en/article/12468. ↩

-

George A. Bournoutian, “Armenians in Iran (ca. 1500–1994),” accessed 15 November 2024, Iran Chamber Society, https://www.iranchamber.com/people/articles/armenians_in_iran1.php. ↩

-

Charles Burton Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, vol. 1 (Singapore: Fraser & Neave, 1902), 283. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Chantal Sajan, “The Straits Times Marks 178 Years As Region’s Oldest Newspaper,” Straits Times, 15 July 2023, https://www.straitstimes.com/life/home-design/the-straits-times-marks-178-years-as-region-s-oldest-newspaper. ↩

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 26 November 1887, 33. (From NewspaperSG); Gretchen Liu, Raffles Hotel (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2006), 18. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING q915.9570613 LIU-[TRA]) ↩

-

Nadia Wright, Linda Locke and Harold Johnson, “Blooming Lies: The Vanda Miss Joaquim Story,” BiblioAsia 14, no 1 (April–June 2018): 62–69. ↩

-

The signatories were Johannes Simeon, Carapiet Phanos, Gregory Zechariah, Isaiah Zechariah, Mackertich M. Moses and Paul Stephens. See Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 283. ↩

-

Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 283. ↩

-

Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 283. ↩

-

Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 283–85; Nadia Wright, “A Tale of Two Churches,” BiblioAsia 13, no. 3 (October–December 2017): 36–39. ↩

-

“Consecration of the Armenian Church,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 31 March 1836, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Wright, “A Tale of Two Churches.” ↩

-

Nadia H. Wright, The Armenians of Singapore: A Short History (George Town, Penang: Entrepot Publishing, 2019), 111. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 305.89199205957 WRI) ↩

-

Wright, “A Tale of Two Churches”; Wright, The Armenians of Singapore, 111–12. ↩

-

Wright, Locke and Johnson, “Blooming Lies: The Vanda Miss Joaquim Story.” ↩

-

“Armenian Relief Fund,” Straits Times, 16 October 1915, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Nadia H. Wright, Respected Citizens: The History of Armenians in Singapore and Malaysia (Middle Park, Vic.: Amassia Publishing, 2003), 52. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 305.891992 WRI) ↩

-

Derek Drabble, “Church With Doors Closed,” Straits Times, 25 December 1949, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Church Services,” Shonan Times, 19 June 1943, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Wright, Armenians of Singapore, 9. ↩

-

Drabble, “Church With Doors Closed.” ↩

-

Drabble, “Church With Doors Closed.” ↩

-

Wright, Armenians of Singapore, 113. ↩

-

Stanley Street, “Notes from a… Malayan Diary,” Straits Budget, 2 July 1953, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The First High Mass in 16 Years,” Straits Times, 9 May 1954, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“So Long, But Now Bishop Is to Take Service,” Straits Times, 24 May 1957, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Friends Plan to Save a Church – And Its Architect’s Home,” Straits Times, 29 April 1954, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Stanley Street, “Lament for Old Landmark,” Straits Times, 7 April 1956, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Arshak C. Galstaun, “No Lament for a Landmark,” Straits Times, 4 May 1956, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

William Campbell, “Singapore Plans to Save Its History,” Straits Times, 7 February 1969, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chia Poteik, “Govt to Keep Eight Landmarks,” Straits Times, 8 July 1973, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“No Resident Priest Since End of World War Two,” Straits Times, 30 December 1978, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Peter Keys, “It’s Simply Charming,” Straits Times, 18 October 1981, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Art Baghramian, “Church Open to Public But Not for Recreation,” Straits Times, 1 November 1981, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Christina Tseng, “Tourists to Wed in Armenian Church,” Straits Times, 12 April 1985, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Maylee Chia, “STPB Plan for ‘Mock-Weddings’,” Straits Times, 24 July 1988, 19. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee Siew Hwa, “Last of the Tribe,” Straits Times, 10 July 1988, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Wright, Armenians of Singapore, 11, 28. ↩

-

Cheong Suk-Wai, “Proud of the Legendary Sarkies Name,” Straits Times, 17 September 2015, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/proud-of-the-legendary-sarkies-name. ↩

-

Geraldine Kan, “Singapore’s Oldest Church Is New Again,” Straits Times, 25 December 1994, 17. ↩

-

Jessie Sarkies, oral history interview by Nur Azlin bte Salem, 28 July 2011, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 8 of 9, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003479), 242–45. For an interview with Jessie and Loretta Sarkies, see also Jamie Ee Wen Wei, “Sisters Are the Last of Sarkies Clan in S’pore,” Straits Times, 19 July 2009, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Cheong Suk-Wai, “‘A Night Out Is Not About the Food, But Music or Theatre’,” Straits Times, 17 September 2015, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/a-night-out-is-not-about-the-food-but-music-or-theatre. ↩

-

“Armenian Church of Singapore Celebrates Major Anniversary,” Orthodoxy Cognate Page, 24 May 2011, https://ocpsociety.org/news/armenian-church-of-singapore-celebrates-major-anniversary/. ↩

-

Camillia Deborah Dass, “Church Rich in Armenian History,” Straits Times, 18 May 2017, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/church-rich-in-armenian-history. ↩

-

Melody Zaccheus, “Armenian Community in Singapore Tells Its Story With New Museum,” Straits Times, 24 May 2018, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/armenian-community-tells-its-story-with-new-museum. ↩

-

Armenian Church Singapore Instagram, 28 March 2022, https://www.instagram.com/p/CboEn4JBdMK/?img_index=1. ↩

-

Pierre Hennes, email correspondence, 23 July 2024. ↩