Remembering the Hawkins Road Refugee Camp

A temporary home for Vietnamese refugees for nearly two decades, the Hawkins Road camp received thousands who experienced daily life within its boundaries and around Singapore prior to resettlement.

By Rebecca Tan

Mention Hawkins Road and most people will return a blank look, even if they live in Sembawang where the now-expunged Hawkins Road was once located. However, back in the late 1970s and up until the mid-1990s, the Hawkins Road Refugee Camp was home to Vietnamese refugees in Singapore.

The camp at 25 Hawkins Road was set up in 1978, occupying the former barracks of the British Army. The fall of Saigon in 1975 had triggered a massive exodus of Vietnamese who escaped from South Vietnam. Most fled by sea and sought refuge in neighbouring countries such as Hong Kong, Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia and Singapore. Referred to as the Vietnamese boat people, they numbered in the hundreds of thousands.

Compound of the Hawkins Road Refugee Camp, 1986. Registered Tourist Guides Association of Singapore Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Compound of the Hawkins Road Refugee Camp, 1986. Registered Tourist Guides Association of Singapore Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Arrival in Singapore

Singapore, being a small country, did not allow all Vietnamese refugees to come ashore. “The agreement worked out with the Singapore Government is that the camp may hold up to 1,000 people, who must be out within three months,” the Straits Times reported in October 1981. Refugees were “allowed ashore only on the condition that they have been picked up by ships flying the flag of a nation which guarantees to take them if no other nation makes an offer”.1

At the Raffles Girls’ School speech day in August 1997, then Deputy Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong explained: “We could not take them into Singapore. If we did, thousands more would come, and we would have been swamped.” The navy was tasked to turn them away. “We had to refuel them, provide them food and water, patch up their boats and engines as best we could, and send them back out to sea and along their way to find some other country better able to take them in.” Many of the soldiers and sailors who took part in what was named Operation Thunderstorm were shaken and chastened by the experience, he said.2

Once a refugee was deemed eligible for the camp, a host of procedures had to be followed. Staffers from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) would proceed to the harbour. The refugees would first undergo a health examination, receive vaccinations and be sent to the hospital if needed. It could take as long as “seven hours after coming in to port” before the refugees were welcomed into the camp. Upon entry, they would receive bowls of hot noodle soup as well as welcome packs containing blankets, sleeping mats and cooking pots.3

“For the first few days, [the refugees] would do little but rest, eat and attempt to take in their new situation,” said the Straits Times. Once the refugees were more rested, they underwent interviews and had their case histories and x-rays taken. They could utilise amenities like a medical and dental clinic, as well as take up vocational training or language classes offered in the camp.4

The Seventh Day Adventist World Service Dental Clinic for the refugees at Hawkins Road Refugee Camp, 1986. Registered Tourist Guides Association of Singapore Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The Seventh Day Adventist World Service Dental Clinic for the refugees at Hawkins Road Refugee Camp, 1986. Registered Tourist Guides Association of Singapore Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Among those who spent time in Singapore was Chan Tho, now 70. He stayed in the camp for about three months in 1979 when he was 26. “We finally made it, we got rescued,” he recalled. “You risk your life, you make it and you say ok, I don’t have to be scared anymore.” He was resettled in the United States and later worked as a civil engineer in Kansas City, Missouri.5

For unaccompanied children, arrangements were made for them to live in special houses with others like them. Thao Dinh stayed in the camp from August 1981 to March 1982 when he was 11 years old and remembers that the house was crowded when he first entered. His father and three younger sisters escaped Vietnam separately and were sent to a refugee camp in Malaysia instead. He was eventually reunited with his family and they resettled in Australia where he worked as a business franchisee. The 53-year-old currently lives in Brisbane.6

Life in Singapore

As the refugees were allowed outside the camp after 12 pm each day for shopping or other recreational activities, they would visit nearby towns like Chong Pang, which took on a “bustling rhythm” reported the Straits Times in 1980.7

The many zinc-roofed shops lining both sides of the main road sold items such as French-made crockery, household products, electrical goods, apparel and luggage. “Business is always better than usual whenever there are batches of refugees leaving to resettle elsewhere,” said Ah Mei, a salesgirl. Some shop owners even picked up Vietnamese and became good friends with the refugees. “I make friends with these people. When they go away to Europe, they write letters and postcards to me,” she added.8

One shop owner kept “pictures of dinner parties held in his shophouses and family snapshots sent from Australia and other countries”. He also told the Straits Times that he and his family of helpers had “adopted” a couple of Vietnamese girls whom they occasionally picked up from the camp to spend the day with.9

Excursions were specially organised for the children. Dinh recalls visiting the nearby towns, as well as beaches and churches. “I can remember taking the double-decker bus to Marsiling, Sembawang and Ang Mo Kio,” he said. The children were chaperoned each time they went out, and also got to celebrate occasions like Christmas and Lunar New Year together in the camp.10

Days in the Camp

In November 1978, a Hawkins Road camp committee was formed by the refugees themselves following a UNHCR official’s suggestion. The committee comprised positions such as an overall camp leader, an internal affairs head, a head of education, a head librarian, a deputy medical officer, a head of carpentry, a chief musician and an officer in charge of films and slides.11

The refugees also took English language classes in the camp. The teaching volunteers concentrated on topics like “how to find jobs, what kind of atmosphere to expect in different types of work, how to handle life in the country the refugees will be resettled in, and the changes in diet, climate and clothing they will face”.12

Gabriel Tan, a Singaporean, volunteered at the camp from 1980 to 1991. Initially he only taught English, but he later got to know the refugees better and even took them on field trips during the weekends.13

In an unpublished manuscript by Jill Saunders, a teacher at the camp, and Kaye McArthur, a coordinator of the children’s programme, they wrote that “you soon forgot the dust, the dirt, the insects and the feeling your clothes were sticking to you from perspiration. Any physical discomfort was overtaken by the task in hand and the refugee’s extraordinary enthusiasm and appreciation”.14

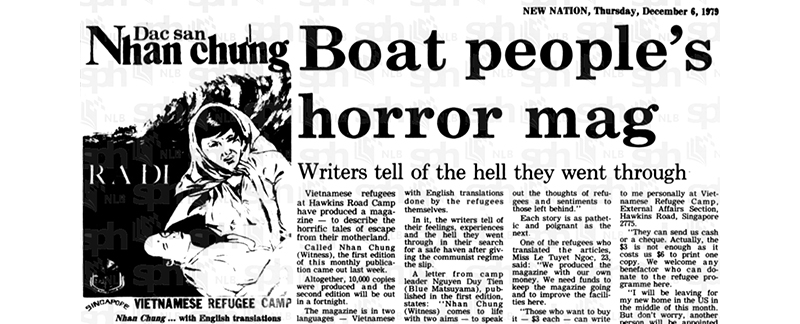

To share stories of their lives, a magazine was produced by the refugees. Titled Nhan Chung (Witness), 10,000 copies of the first issue came out in December 1979. It was written in Vietnamese, with English translations done by the refugees themselves.15

“Nhan Chung (Witness) comes to life with two aims – to speak out the thoughts of refugees and sentiments to those left behind,” explained camp leader Nguyen Duy Tien. Le Tuyet Ngoc, who translated the articles, said that the magazine was produced with the refugees’ own money.16

The second issue was planned for publication in early 1980, after Singapore’s Ministry of Culture had given approval.17

While the first issue focused on the refugees’ tales of escape from Vietnam, Ha Van Ky, a former high school teacher who served as the magazine’s editor, planned for the second issue to contain 21 articles about the refugees’ search for new homes, life in Vietnam as well as the Christmas celebration held at the camp. “How we fled from Vietnam, our encounters with sea pirates, and the experiences of Vietnamese women sold to slavery will be some of the stories told in the magazine,” said Ha.18

The second issue was never published though. “After discussions with the Culture Ministry, it was decided that the magazine should be discontinued because the refugees were too enthusiastic about it,” said UNHCR official Luise Drüke. “There were too many contributions and the volume got too big to handle.”19

Unfulfilled Promises

The camp received multiple lease extensions before eventually closing in 1996. The original lease was extended to December 1981, and a second extension to 30 June 1982 was also approved. Although the land occupied by the camp was slated for industrial development, a third lease extension was requested. “The arrival pattern of refugees is continuing,” said UNHCR representative Sashi Tharoor. “For this reason, the UNHCR felt there is still a need for the camp.”20

Among the resettled was Nguyen Van Loc, the former South Vietnamese prime minister. Originally in a category which “disqualified him from [resettlement in] the US”, his association with the South Vietnamese government was evaluated and later “accepted as grounds for his resettlement in the US”.21

Not all refugees were so fortunate though. Some countries did not fulfil their resettlement guarantees, leading about 60 camp inhabitants to go on a hunger strike in November 1992. The refugees protested the failure of seven Western countries – the United States, Britain, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Germany – to accept them. During the strike, two men “swallowed an overdose of anti-stress pills”, another man “poured kerosene down his throat”, while 16 others became unconscious and were taken to Tan Tock Seng Hospital.22

A few months prior to the strike, a 14-year-old girl of mixed Vietnamese and American parentage attempted suicide after she was told she would have to return to Vietnam. “I cannot go back. I was treated very badly because my father was an American soldier. I have no future in Vietnam,” Ngoc Nguyen Hiau told the Straits Times.23

The refugees even took their protest to the UNHCR office at International Plaza. However, despite the refugees’ six-month-long protest, all the seven countries remained unmoved. They had made their resettlement promises when their economies were expected to improve, but that did not happen. Hence, they later classified the Vietnamese as “economic, and not political, refugees, and so ineligible to be resettled in their lands”.24

Moving Out and On

The last of the refugees only left Singapore on 27 June 1996 after the UNHCR decided to shut down all camps in the region. The 99 of them were met by the police, brought to an immigration depot where they were held for two weeks, and then finally boarded a Vietnam Airlines plane at Changi Airport bound for Ho Chi Minh City.25

Lu Cheng Yang, the Controller of Immigration, said at a press conference on the day of their departure that the refugees “had been allowed to enter Singapore because of unconditional written guarantees by seven countries to resettle them within three months of their arrival”. However, these countries did not honour their commitments and so the Vietnamese were “stranded in Singapore, many since the early 1990s”. He added that Singapore had worked with the UNHCR and the Vietnamese government to arrange for their return.26

When these refugees left for Vietnam, they had saved an average of S$3,000 each and gained other skills like the ability to speak English; one person was reported as having saved as much as S$18,000. They had been allowed to find jobs as cooks, waiters and more. Danilo Bautista, head liaison officer at the UNHCR office in Singapore, noted that the Singapore government had given each refugee US$760 (S$1,070) as a gesture of goodwill, and that they would each be given US$240 more after arriving in Ho Chi Minh City. Ultimately, the departure went without incident.27

The former residents of Hawkins Road Refugee Camp have resettled all over the world and they have since set up a Facebook group to exchange photos and maintain contact with one another. Some have even come back to Singapore to visit the former campsite and recall memories of life here.28

Interestingly, some of the former refugees have also returned to Singapore to settle down. One of these is Yen Siow, who was resettled in Australia. She relocated to Singapore in 2015 with her Singaporean husband. In August 2016, she decided to track down her Norwegian saviours and managed to contact one of them, Bernhard Oyangen, through Facebook. Siow and Oyangen met in October that same year when the latter stopped in Singapore en route to New Zealand. Siow recounted that at the reunion, she had said to him: “‘Mr Bernhard, these are my children, and without your team and your captain, they wouldn’t be around today’.”29

Another former refugee now living in Singapore is Vinny Nguyen. Nguyen stayed in Hawkins Road for a month in 1981 when he was six years old. He was resettled in the United States, and after graduating from university in California, joined a multinational IT company. He was then offered a job posting to Singapore, where he met his Singaporean wife. Their two children attend local schools, and he has been living in Singapore since 2003.

Nguyen said his memories of Hawkins Road were pleasant ones. “At six or seven years old, everything’s a field trip and exciting,” he recalled. “I remember playing a lot, playing more than anything.” He also remembers being taken on outings to places like the Singapore Zoo. “Singapore always took care of everyone well,” he said.30

Singapore’s experience taking in the Vietnamese refugees came to shape its policy regarding refugees. Speaking in Parliament in 1998, Home Affairs Minister Wong Kan Seng said that Singapore was a small country with limited resources and could not accept anyone who claimed to be a refugee. “We would otherwise be easily overwhelmed by sheer numbers. This would lead to a grave national, social and security problem.” He noted that in the past, Singapore had accepted Vietnamese refugees on the ground that a third country guaranteed to take them. However, not all these countries honoured their promise and “we were saddled with the Vietnamese refugees for a long time. We have learnt our lesson and will no longer accept any refugees even if third countries promise to resettle them”.31

Rebecca Tan is a Children and Teens Librarian at Toa Payoh Public Library. She develops content and services for children and teens, and works with schools to promote a culture of reading. She was previously a Digital Heritage Librarian at the National Library.

Rebecca Tan is a Children and Teens Librarian at Toa Payoh Public Library. She develops content and services for children and teens, and works with schools to promote a culture of reading. She was previously a Digital Heritage Librarian at the National Library. Notes

-

Linda Agerbak, “A Price for War,” Straits Times, 24 October 1981, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Boat People of Vietnam and What Could Happen to Singapore,” Straits Times, 24 August 1997, 24. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Agerbak, “A Price for War.” ↩

-

Agerbak, “A Price for War.” ↩

-

Chan Tho, interview, 11 June 2024. ↩

-

Thao Dinh, interview, 11 June 2024. ↩

-

Chua Ngeng Choo, “A Little Viet Refuge,” Straits Times, 1 November 1980, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chua, “A Little Viet Refuge.” ↩

-

Chua, “A Little Viet Refuge.” ↩

-

Thao Dinh, interview, 11 June 2024. ↩

-

Paul Jansen, “Viet Refugee Camp Model of Harmony,” Straits Times, 22 January 1979, 25. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Committee Makes Life Pleasant, Meaningful,” Straits Times, 22 January 1979, 25. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gabriel Tan, interview, 8 July 2024. ↩

-

Jill Saunders and Kaye McArthur, “Hawkins Road and Gelang Refugee Camps 1981–1983: Volunteers Memories” (unpublished manuscript, 18 July 2024). ↩

-

“Boat People’s Horror Mag,” New Nation, 6 December 1979, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Govt Gives the Nod to Refugee Mag,” New Nation, 15 February 1980, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Refugee Magazine Folds Up,” New Nation, 20 May 1980, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Govt Asked to Extend Lease on Refugee Camp,” Straits Times, 24 March 1982, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan Lian Choo, “Loc Gets Green Light to Resettle in US,” Straits Times, 31 May 1983, 40. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“16 Refugees on Hunger Strike Here Fall Ill,” Straits Times, 23 November 1992, 1; “West’s Broken Promises Provide Bitter Lesson,” Straits Times, 28 March 1998, 62. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Vietnamese Refugee Attempts Suicide After Bid to Resettle Fails,” Straits Times, 21 November 1992, 27. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“West’s Broken Promises Provide Bitter Lesson”; “Last 99 Boat People in Singapore Leave,” Straits Times, 28 June 1996, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Last 99 Boat People in Singapore Leave”; “West’s Broken Promises Provide Bitter Lesson.” ↩

-

“Vietnamese Boat People Refugee Camp, 25 Hawkins Road, Sembawang, Singapore,” Facebook, accessed 28 March 2024, http://www.facebook.com/groups/25hawkins. ↩

-

Yuen Sin, “36 Years On, Ex-Refugee Meets One of Her Rescuers,” Straits Times, 23 October 2016, 7. (From NewspaperSG); Former Vietnamese Refugee Meets One of Her Rescuers 36 Years Later,” Stomp, 23 October 2016, https://stomp.straitstimes.com/singapore-seen/singapore/former-vietnamese-refugee-meets-one-of-her-rescuers-36-years-later. ↩

-

Vinny Nguyen, interview, 5 July 2024. ↩

-

“Govt Taking Tough Stance on Illegal Immigrants,” Business Times, 14 March 1998, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩