The Search for a “Lost” Towkay of Malaya

A man looks at his grandfather with new eyes after a mysterious envelope is found in an old workman’s outfit that was about to be thrown away.

By Phan Ming Yen

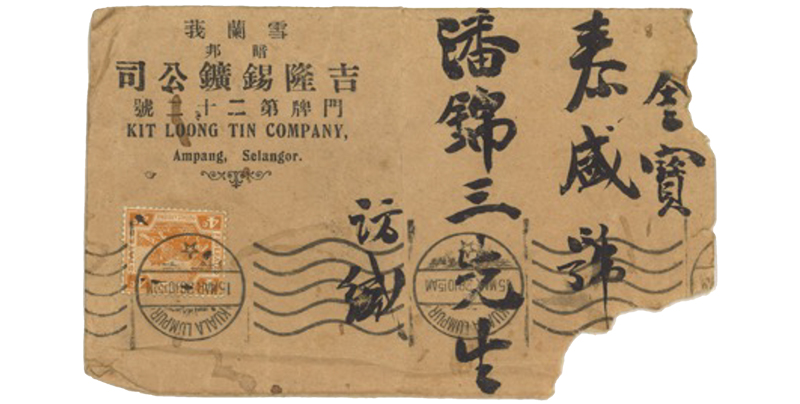

It all started with a name on a torn envelope postmarked 15 March 1928: 潘锦三 (Phan Kim Sam).1 My brother and I came across the envelope in the breast pocket of what appeared to be workman’s clothes, which I was about to discard until my brother thought it wise to check the pockets first. Imprinted on the clothes, too, were the initials “P K S”.

We had found these garments while packing the family house in early 2023, a pre-World War II shophouse in the former tin mining town of Kampar in Kinta Valley, Perak, Malaysia. We had started with the first cupboard that was accessible to us in the largest bedroom in the house. These clothes were among the first items we found. The shophouse had not been inhabited since our ageing aunt moved to Kuala Lumpur two years before the pandemic to be with our cousin. They are the two sole surviving members from our paternal side of the family.

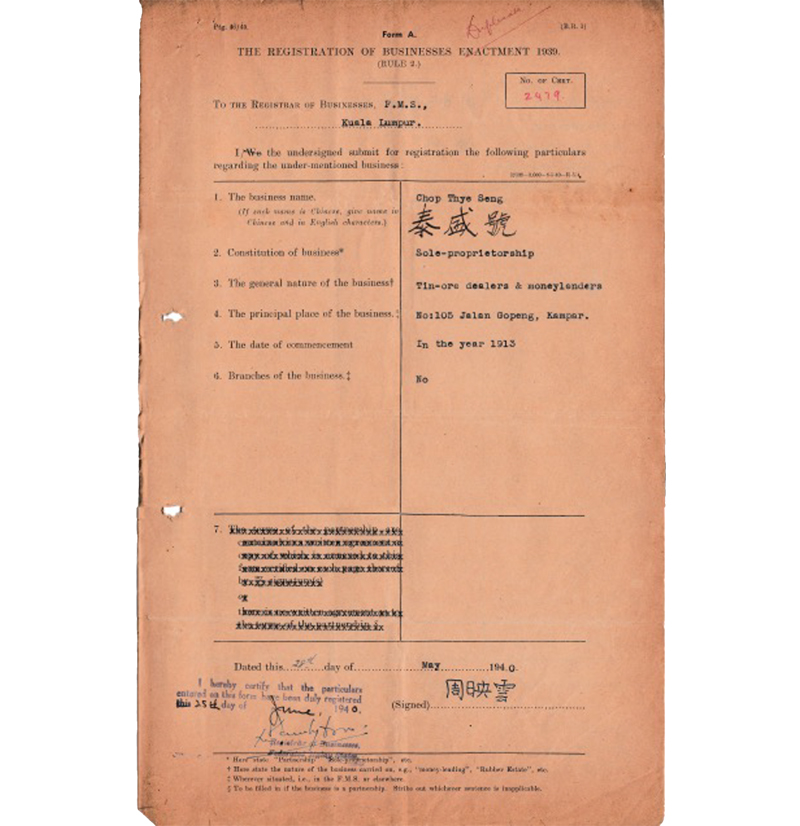

The family name on the envelope was ours: 潘. But we did not recognise the given name 锦三. Also written on the envelope were the Chinese characters 泰盛, 金宝. The first two characters, 泰盛, was Thye Seng,2 which was the name of the tin-ore dealing3 business that our grandfather had founded in prewar Kampar (金宝).

He had died from an aneurysm two years before the outbreak of the war, so we had been told. He had plans to bring the family of nine children back to China, having built a huge house in his birthplace, Meixian (梅县) in Guangdong province, with the money he made in Malaya.

Our grandfather’s name was 潘扬昌 (Fong Kam Sum). That was the name on the ancestral tablet at home and on his tombstone. It was the name our mother knew him by and it was also the name whom our cousin, who had lived in the shophouse in the late 1950s, was familiar with. None of them had ever heard of the name 潘锦三. Our aunt, now 94, is stricken with dementia.

The family business was subsequently passed on to our grandmother, Choo Yang Yung, and managed by our uncle and aunt. Our father, the youngest in the family, worked as a forensics document examiner with the Malaysian civil service in Petaling Jaya, Selangor. With the passing of our grandmother in 1995, the business was managed by our uncle. After he died in 2003 and given the falling tin prices in Malaysia since the 1980s, the business licence was given up.

As children, we – or at least I – seldom asked about our grandfather, preferring to just absorb whatever that was willingly shared with us. Perhaps it seemed to me then that everyone focused on working hard and living in the present for the future: the concern of our grandmother and aunt was always the education and careers of the grandchildren.

Up to the point when we found the envelope, this was what we knew about our grandfather and the family: he was Hakka; he had three wives – two from China, and the third, whom he married in Malaya, being our grandmother. Of his nine children, four were born from our grandmother. We were never told the names of the other five: three adopted elder sons and two elder daughters whose births we were uncertain of.

We knew a few other interesting facts about our grandfather. He liked art, and had sold chwee kueh (steamed rice cake served with preserved radish) when he first arrived in Malaya, probably around 1909.4 He had loaned money to a tin miner who, in return, passed him tin concentrates. He removed the impurities from the concentrates and resold the tin to smelting agencies.5 Before moving to Malaya, he had worked in Indonesia and returned to China. He was also very caring towards our grandmother. Our father seldom spoke about our grandfather and the business. After all, he was only a child of five when his father died.

The past, as novelist L.P. Hartley notes, is a foreign country.6

Finding that envelope addressed to 潘锦三 was a first step into that foreign country. There were three letters inside the envelope: two (from the same signatory) addressed to a 扬叔 (“Uncle Yang”), and another to 父親 (“father”) from a different signatory. We did not recognise the names of both senders.

Attempting a search on variations of 潘锦三, in romanised form (and in original Chinese), in NewspaperSG, the National Library Board’s online resource of over 200 Singapore and Malaya newspapers, turned up an article in the Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle dated 10 February 1939, with the headline “Funeral of Kampar Towkay”.

The article stated that at the funeral of Phan Kim Sam, “well over 400 attended to pay their last respects”: “Towkay Phan Kim Sam who was 68 was a miner by profession and was a well-known tin-ore dealer. He took interest in the social activities of the town. He leaves behind two widows, five sons, four daughters, two sons-in-laws, a grandson and many other relatives. The funeral procession started at 2 pm from his residence at Jalan Gopeng.”7

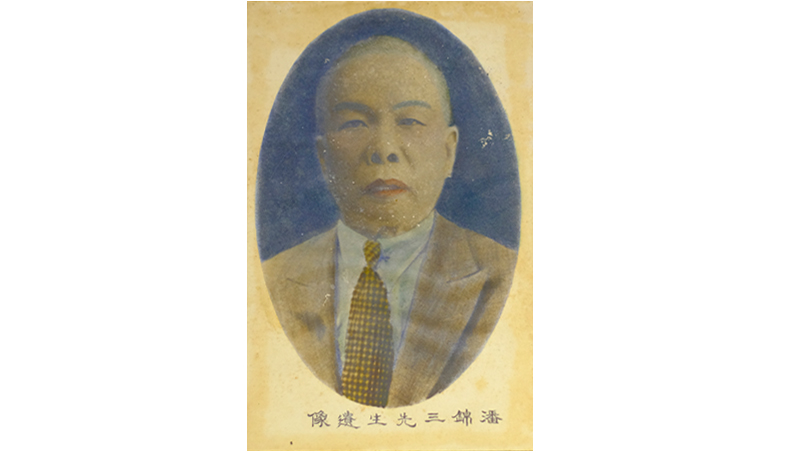

We discovered that “Phan Kim Sam” shared a number of similarities with our grandfather: the same profession, the same number of children and whose gender were also similar to what we knew, almost the same number of wives8 and he lived on the same road. We later found – tucked away on the topmost compartment of a wardrobe – a 1.6-metre-long panoramic print of the funeral with the Chinese text “中华民国28年2月8日金宝闻人潘锦三先生出殡时留影纪念 怡保埠 广州摄” (“Commemorative photograph from the funeral procession of renowned Kampar figure Mr Phan Kim Sam on 8 February 1939”)9 and a colourised photograph of a man with the name 潘锦三. The man in the photograph bore a strong resemblance to a portrait of our grandfather that hung in the office of the shophouse for as long as we could remember.

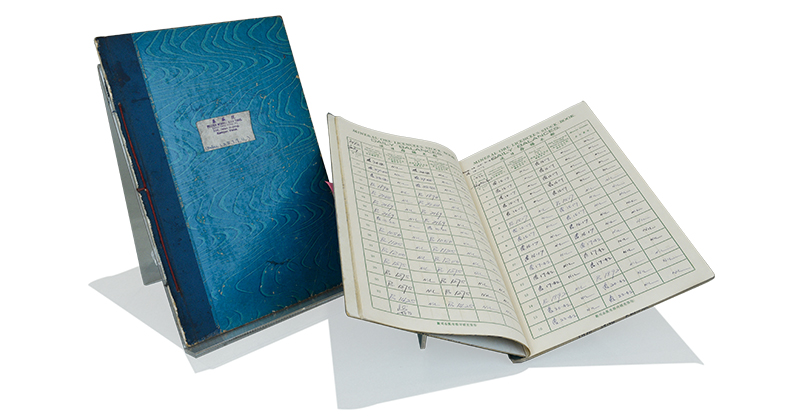

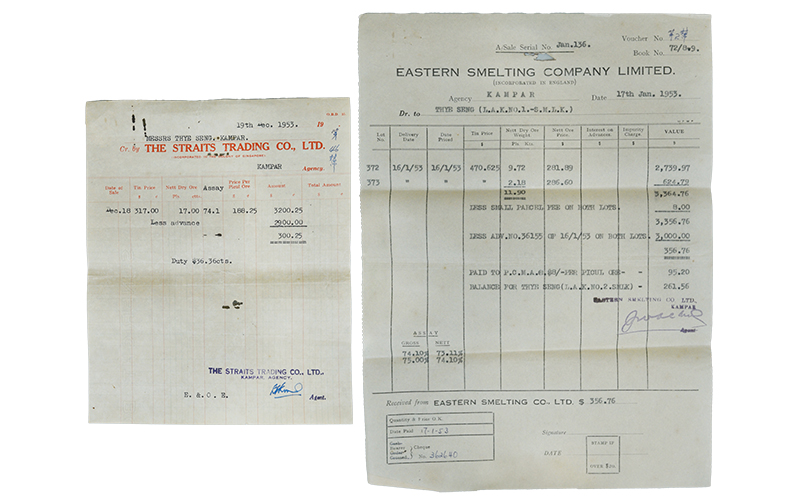

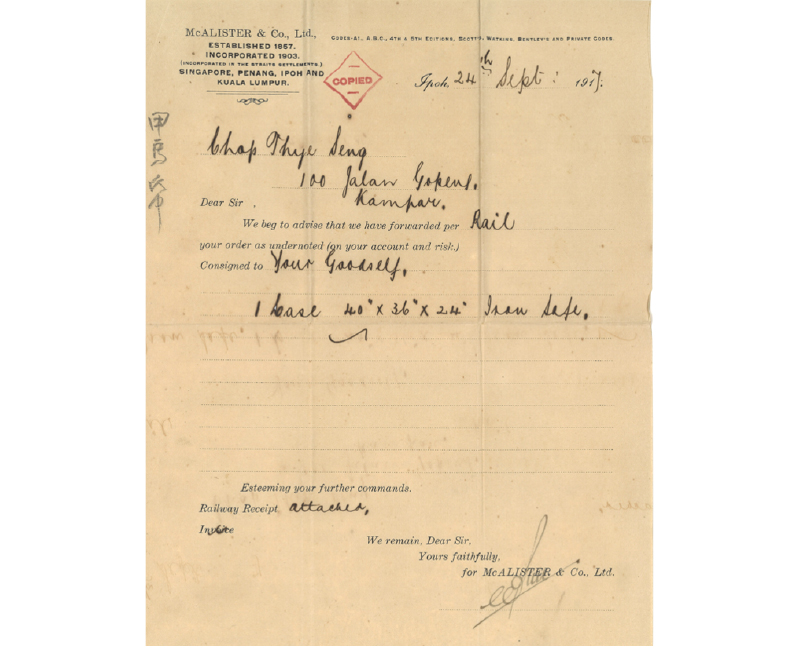

We spent the next few months searching for written evidence that 潘锦三 and 潘扬昌 were the same person. It was a search that also uncovered close to a century of business and other documents pertaining to my grandfather’s company, Thye Seng: volumes of ledger books dating back to the 1920s that documented daily transactions and the names of those whom the family had business with, shares in tin mines prior to the war, receipts of sales and purchase, and invoices. The earliest record we found dates to 1917 for the purchase and delivery of a safe, which still remains in the shophouse today.

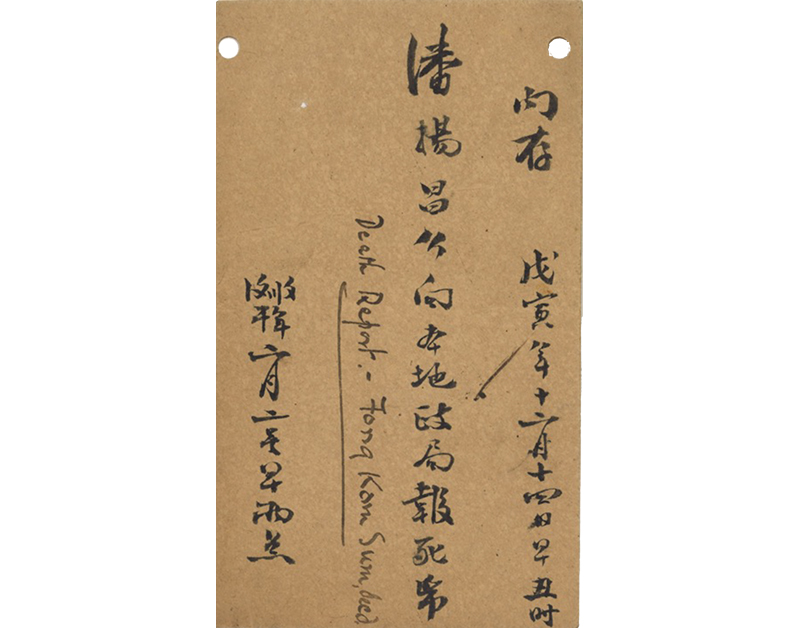

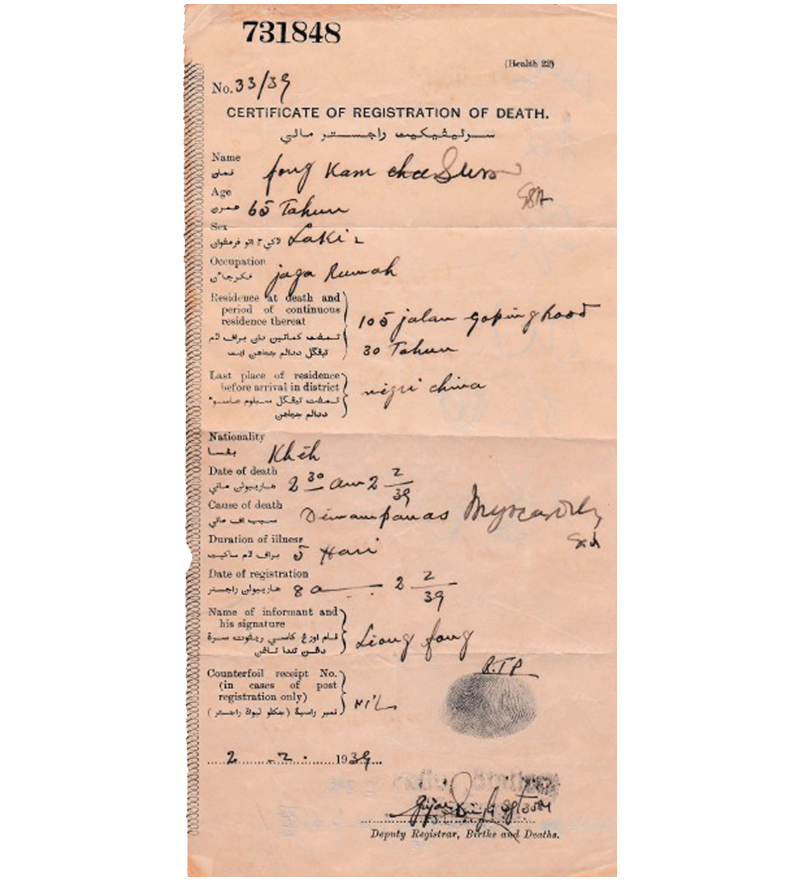

Ascertaining that 潘锦三 and 潘扬昌 were one and the same in a written document was another matter. Our father’s birth certificate showed his father to be “Fon Yong”. A subsequent discovery of an envelope that contained a death certificate was marked with the name “潘扬昌” with the English words “Death Report – Fong Kam Sum decd”, the name as recorded on the certificate itself.10

Fong Kam Sum’s age was recorded as being 65, and the cause of death written in two hands: the first, demam panas, which could be translated as “high fever”, and the second is “myocarditis”. Oddly enough, for his occupation, it was recorded as jaga rumah or “watchman”. My grandfather was not a watchman but it is possible that the person who reported Phan’s death assumed the official recording the matter was asking for his occupation rather than Phan’s.

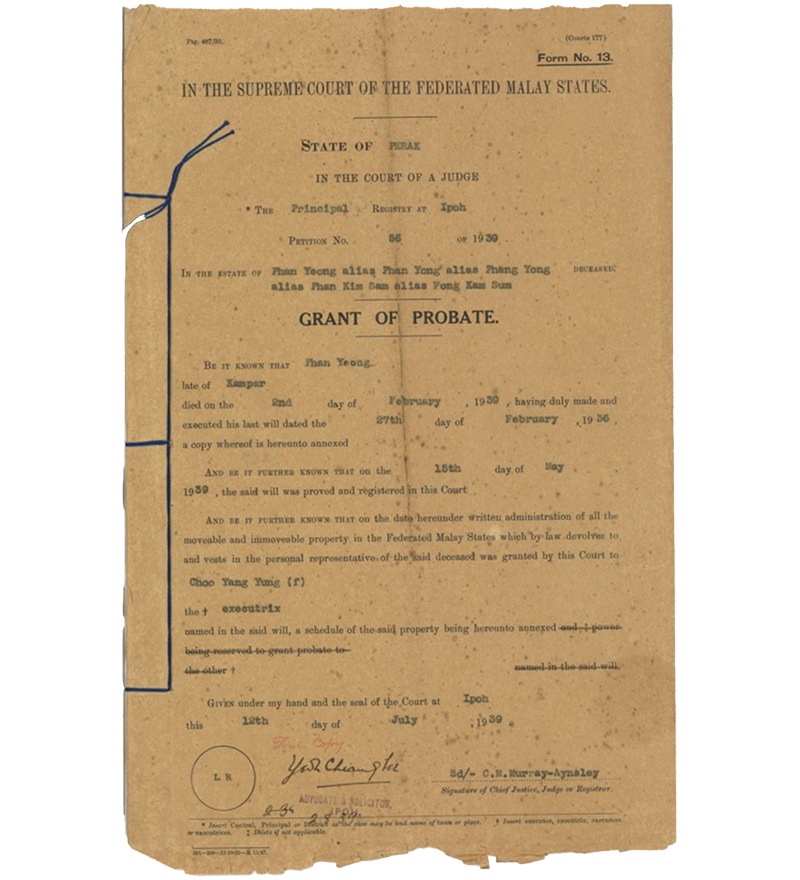

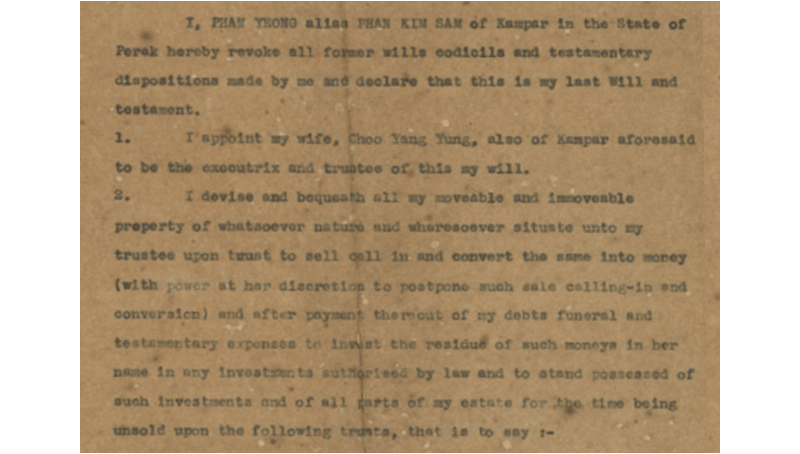

Relief came when a grant of probate was found in an old leather briefcase with the following name and aliases: “Phan Yeong alias Phan Yong alias Phan Kim Sam alias Fong Kam Sum”. Phan’s will begins with “I, Phan Yeong alias Phan Kim Sam of Kampar in the State of Perak hereby revoke all former wills codicils and testamentary dispositions made by me and declare that this is my last will and testament”.11

The will also named our grandmother, Choo Yang Yung, as executor and trustee, and our father as his natural born son. 潘锦三 was, therefore, most likely the courtesy name – a name bestowed upon one at adulthood in addition to one’s given name12 – of 潘扬昌.

The search for more details on the life, activities and contributions of my grandfather and his subsequent impact on the community around him continues. There was a recent talk on small towns in 1930s Malaya co-organised by New Era University College (NEUC) and my family. It was held at our shophouse – which we have since restored as a heritage, event and creative residency space.13 At the talk, we learned that research by a NEUC doctoral candidate on the prewar history of Kampar had unearthed more information in official documents of a tin miner called Phan Sam, likely to be an early diminutive of Phan Kim Sam.

Apart from the use of courtesy names and diminutives, the situation is further complicated by the fact that in the past, most officials were likely to have recorded names in English as they heard spoken to them and that majority of the immigrant and indigenous population of Malaya were unfamiliar with the English language. As a result, variations in spellings of names and diminutives naturally arose. A cross-checking of documents – such as wills, and birth, death and citizenship certifications, and identity documents – to ascertain the identity of a single person could sometimes reveal a multitude of variations on the spelling of a single name.

Perhaps this venture into the foreign country of one’s past is also a reminder of the second part of Hartley’s quote: “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” And that difference is what makes the dialogue between a historian and his/her facts, a never-ending one, bringing forth new narratives and retellings of the past for the future.

The author thanks Phan Ming Ruey, Mdm Lau Foong Kheng, Lee Ee Pieu, Dr Wong Yee Tuan, Jacky Chew, Chai Wei Sin, Chanel Pong, Ansell Tan and Sun Yu-li for insights into the history of Phan Kim Sam and Thye Seng. Thye Seng at 105 Jalan Gopeng, Kampar, Malaysia, is open to visitors by appointment. Contact the Phan family at rueyphan@yahoo.com for more information.

Phan Ming Yen is an independent writer, researcher and producer. A former journalist and arts manager, his current areas of research are on the Malayan Campaign and Japanese Occupation in Singapore. He has written about 19th-century music in Singapore and also on the Syonan Symphony Orchestra during the Occupation.

Phan Ming Yen is an independent writer, researcher and producer. A former journalist and arts manager, his current areas of research are on the Malayan Campaign and Japanese Occupation in Singapore. He has written about 19th-century music in Singapore and also on the Syonan Symphony Orchestra during the Occupation. Notes

-

Letter addressed to Phan Kim Sam, 15 March 1928. (“Pan Jinsan” in hanyu pinyin.) ↩

-

See “Registration of Business Enactment 1939” dated 28 May 1940. Thye Seng was founded in 1913. ↩

-

Yip Yat Hoong, The Development of the Tin Mining Industry of Malaya (Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press, 1969), 29–32. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 338.27453 YIP). One of the main features of the tin-ore dealing business was that of tin-ore dealers giving loans to marginal miners. These miners in return would sell the concentrates from their mines to the dealer in settlement of outstanding debts. The tin-ore dealer then acted as an agent for these miners, selling the tin-ore to either The Straits Trading Co., Ltd. or the Eastern Smelting Company Limited for smelting and refining. ↩

-

Phan Kim Sam’s death certificate states that he had been residing in Malaya for 30 years at the time of his death. Research is still ongoing to ascertain his exact date of arrival in Malaya. ↩

-

Yip, The Development of the Tin Mining Industry of Malaya, 29–32. ↩

-

The quote “The past is a foreign country” is the opening line of novelist L.P. Hartley’s (1895–1972) novel, The Go-Between, published in 1953. See L.P. Hartley, The Go-Between (London: Penguin, 2020). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. HAR) ↩

-

“Funeral of a Kampar Towkay,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 10 February 1939, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Little is known about Phan Kim Sam’s first two wives other than their family name. It is the author’s conjecture that the eldest of the three wives could have passed on by the time of his grandfather’s death in 1939. ↩

-

The print of the funeral is now with the National Library Board, Singapore. ↩

-

Death Certificate of Fong Kam Sum, 2 February 1939. ↩

-

Grant of Probate of Phan Yeong alias Phan Yong alias Phan Kim Sam alias Fong Kam Sum. ↩

-

“Courtesy Name,” My China Roots, last accessed 4 June 2024, https://www.mychinaroots.com/wiki/article/courtesy. ↩

-

泰盛锡米店首办讲座反应热烈打造文艺写作驻地空间 [Thye Seng store’s first lecture received an enthusiastic response and created a literary and artistic writing resident space], Sin Chew Jit Poh, 7 May 2024, https://perak.sinchew.com.my/news/20240507/perak/5589314. ↩