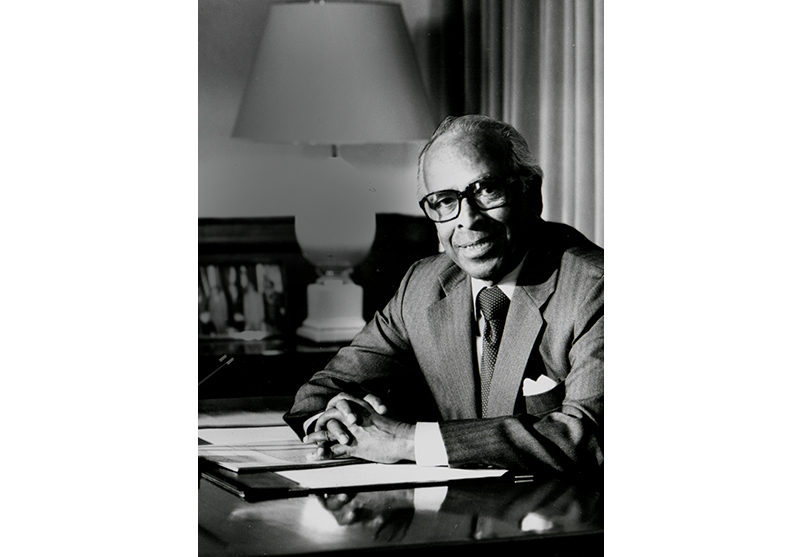

S. Rajaratnam: The Lion’s Roar

The second volume of S. Rajaratnam’s authorised biography – The Lion’s Roar – was launched in July 2024. In her introduction to the book, extracted here, author Irene Ng explains how the journalist-turned-politician was a critical figure in Singapore’s early years.

By Irene Ng

“You can make the tomorrow you want, provided you have the wisdom, the guts and the will to struggle for it.” This sentence captures in a nutshell the guiding philosophy of S. Rajaratnam, who stands out among the founding leaders of Singapore as its chief national ideologue and foreign policy strategist.

This philosophy, with its emphasis on the future and the power of the human spirit, had been a basic premise of his political ideology long before he entered politics in 1959, and even longer before Singapore became independent in 1965. It was a dictum that was put to the test in his own eventful life. As a founding leader of the People’s Action Party (PAP) who went on to hold multiple key ministerial portfolios, he lived out his faith in unfathomable circumstances. Heartbreak, anxiety and despair hovered constantly over his attempts to overcome them.

Yet, his guiding belief in the power of the human will did not come naturally to him; neither did it come easily. Born on 25 February 1915 in Jaffna, Ceylon, he was a child of the colonial era, when Ceylon, India, Malaya and large swathes of the world were part of the British Empire. He was also a child of several identities not of his own making. In his original birth certificate, his name was registered in Tamil script as Rajendram (which can mean “God among Kings” in Sanskrit), thanks to his maternal grandfather in Ceylon. That changed after he turned six months old – his mother, Annammah, brought him to Seremban, Malaya, to join his father, Sinnathamby, a supervisor in a rubber estate. There, his devout Hindu parents consulted the family priest and astrologer, and renamed him Rajaratnam (“Jewel among Kings”).

In the rubber estate, Raja, as he was usually called, found himself the latest addition to the generations of Jaffna Tamil immigrants who had settled in the area. He grew up in an environment in which blood relations, tradition and tribe largely defined one’s world. His religious elders believed that one’s destiny was written in the stars, that one’s fate was determined at birth, by one’s horoscope, and could not be fully escaped. From young, he watched them consult the astrologer on anything and everything – be it choosing a marriage partner, starting a new job, or even determining an auspicious time to leave their house in the morning.

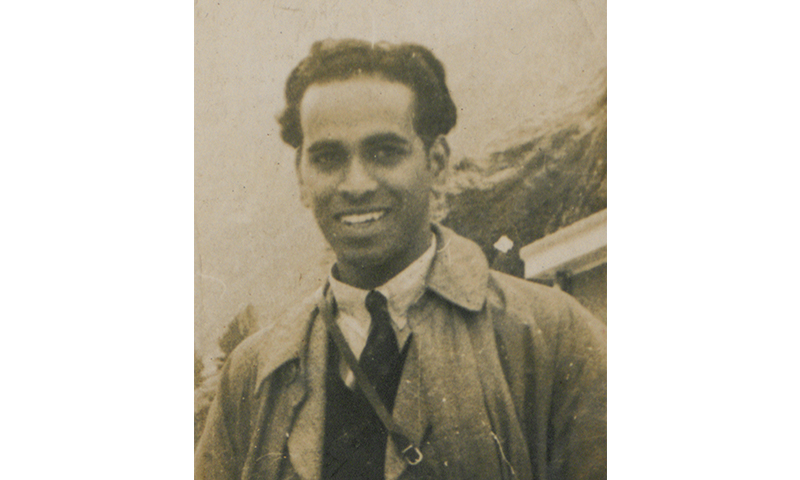

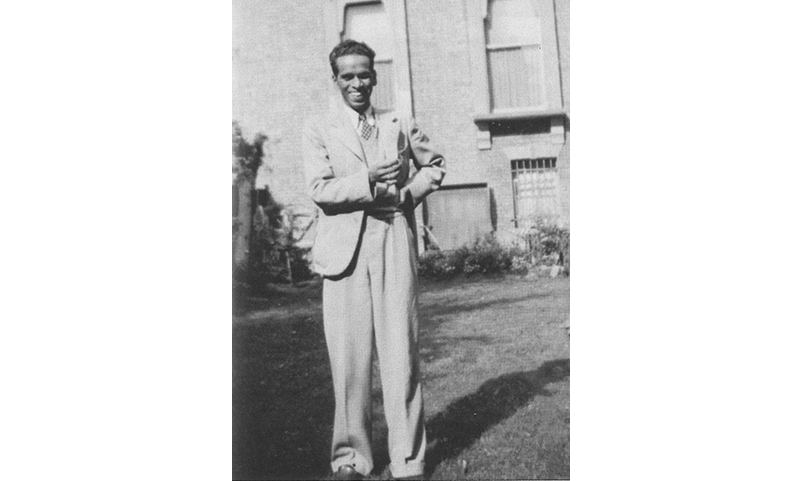

My first volume of Raja’s biography, The Singapore Lion, describes how he struggled with this fundamental notion as a young man; how he had his political awakening in London as a law student in King’s College from 1935, flirted with Marxist theory and found his gift as a writer as well as love with a Hungarian woman, Piroska Feher. It also relates how the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 changed everything for him. His real university was not King’s College, from which he dropped out in 1940, but war-time Britain, where he learnt that politics was literally a matter of life and death.

At the age of 32, Raja returned to Malaya in 1947 with his new wife, Piroska, and a resolve to shape his own fate as well as that of his country, Malaya, of which Singapore was an inextricable part. He had found his calling: to fight for independence for his own country, and to usher in the post-colonial society to come.

He became a journalist, using the power of words and ideas to stir people to action and to bring about change. His main vehicles were English-language newspapers the Malaya Tribune and the Tiger Standard, also known as the Singapore Standard.

His byline became a force in national politics as he crusaded against colonialism, communism and communalism. Besides writing for local radio and newspapers – which in those days were circulated in both Malaya and Singapore – he also worked as a stringer for foreign news agencies such as the London Observer News Service, the Pan-Asia Newspaper Alliance and JANA: The News Magazine of Resurgent Asia and Africa.

Raja fought for more than a decade for the independence of his people in Malaya. They had been dominated, divided and exploited by the British for more than a century, and he rebelled against this. In 1954, together with his anti-colonial allies, he formed the left-wing PAP, led by Lee Kuan Yew.

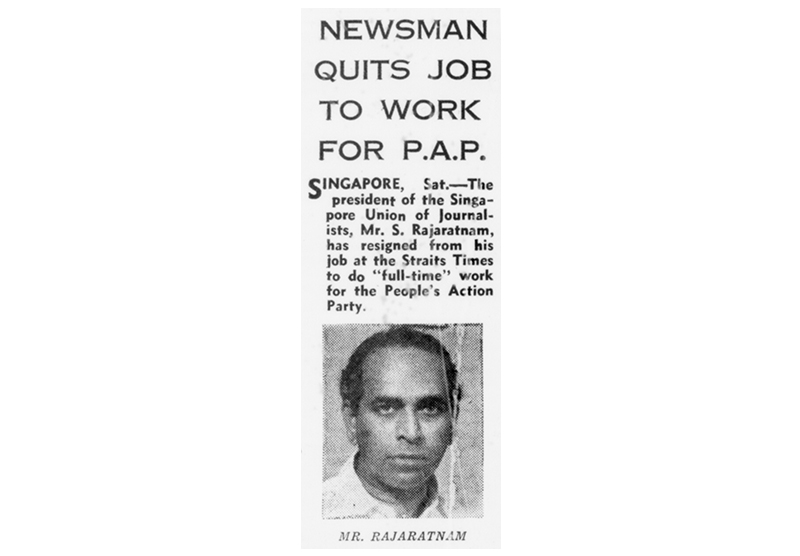

When the British gave Malaya – but not Singapore – its independence in 1957, he mounted another struggle – this time for Singapore’s independence through merger with Malaya to form Malaysia. His entrance to politics was announced in a five-paragraph article in the Sunday Times on 29 March 1959. Headlined “Newsman Quits Job to Work for PAP”, it told readers simply that Raja, 44, the president of the Singapore Union of Journalists, had resigned from his job at the Straits Times to do “full-time” work for the PAP.

When the PAP swept to power in self-governing Singapore in 1959, Raja, who became the country’s first culture minister, stood out even among the most ideological leaders driving the merger campaign. He had long imagined Singapore and Malaya as one entity, as one “nation in the making” – to use the title of his 1957 radio play – and had considered their eventual union as necessary, if not inevitable. He was elated when the union finally materialised in 1963.

For Raja, at least at that point, nothing was more important than building a united Malaysia, where people of all races would be equal. That was his big dream, his lodestar. His abhorrence of colonialism, of the exploitation of man by man, of racial discrimination and prejudice, had a moral rather than a political motivation.

The Singapore Lion ended with the merger in 1963, with a glimpse of the troubles to come. This second volume, The Lion’s Roar, covers the period from Singapore’s merger with Malaya to form Malaysia in 1963, to his death in 2006.

It traces Raja’s crusade for a “Malaysian Malaysia” during the merger years, and its tragic end. It charts his subsequent odyssey to fight for Singapore’s survival as an independent country and to create the national ideology of a country born in turbulent times. It reveals the mistakes made along the way – from inexperience, miscalculation and sheer desperation – and the efforts to overcome the dramatic reversals that threatened to destroy his dreams.

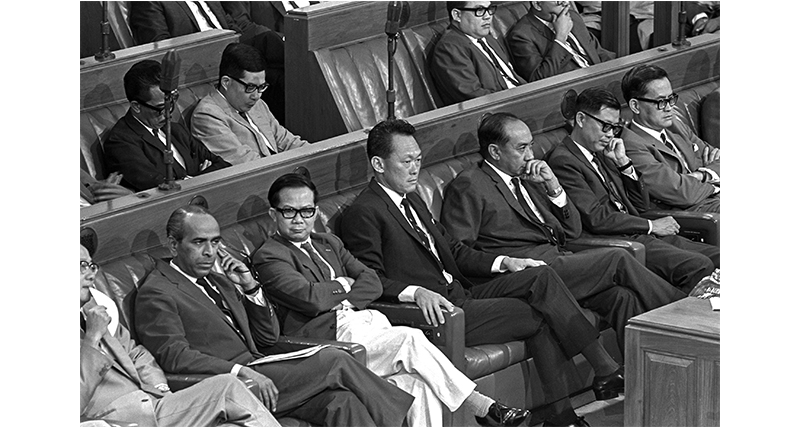

Raja came from a special generation of Singapore leaders – larger than life, tough, brilliant, complex people. Forged in life-and-death battles, they shared a fierce drive to succeed.

Besides Raja, the core leaders of the first-generation Cabinet were Lee, the country’s prime minister; Goh Keng Swee, the finance minister; and Toh Chin Chye, the deputy prime minister. While there were other ministers pulling their weight, it was essentially these key leaders who made the critical decisions that decided Singapore’s fate at its most vulnerable moments.

But Raja had some qualities that set him apart. The depth of his convictions, the breadth of his interests, and the length of his vision made him an exceptional figure, as did the power of his prose and polemics. But he had something more than that – an almost limitless imagination paired with fearless audacity. It was these qualities that helped to infuse his dispirited colleagues, including Lee, and a doubting nation with a sense of optimism and self-confidence in the most dire hours of independence, when they did not know whether Singapore was going to

Of all the varied chapters in Raja’s tumultuous life, the story of his struggle for a Malaysian Malaysia, and then a Singaporean Singapore, is one of the most insightful in terms of the clues it provides into his character and motivations.

Raja’s abiding vision was to build a progressive society that was just and fair, and that provided equal opportunities and rights for all, regardless of their race, language or religion. “Regardless of race, language or religion” had long been his leitmotif. By this he meant creating a new social and political order in which these factors did not enter into the country’s economic and political calculations.

It counts as one of his most powerful ideas. It became his signature, his lifelong obsession. It was encapsulated in the Singapore Pledge, which he drafted in 1966. Among the founding fathers of Singapore, he occupies a special place in its history for pursuing this vision with a high heart.

His politics, however, came with an equally high price of personal hardship and pain. Like most visionaries ahead of their time, he found himself in many instances having to face the agonies of shattered hopes and unfulfilled dreams.

But unlike some others, after every obstruction, every catastrophe, Raja somehow reinvented himself and revivified his dreams. With his genial smile and contagious optimism, he was buoyed by the unshakeable conviction that someday, all that he had struggled for would come to fruition, even if it might not be in his lifetime.

Certainly, he was not alone in his desire to build a non-communal and meritocratic Singapore that was open to the world – a Singaporean Singapore, as he called it. But, more than anyone else in the early decades of Singapore’s evolution, he became its symbol and its spokesman. Yet he was not typical of the times, nor was he the archetype of Singapore’s national character – for that, too, was still a work in progress. What Raja was, was the essential Singaporean.

It might seem strange that such a person – a Jaffna Tamil born in Ceylon and raised in Seremban, a university dropout who spent 12 years in London mixing with progressive Afro-Asian writers and radical thinkers – should have come to embody this. I would argue the opposite: only by standing outside of the conventional concepts that made up Singapore then, could someone reimagine and remake Singapore, as Raja sought to do.

As this book shows, only a man with his set of experiences, interests and ideas could have envisioned Singapore transforming into a “global city” at a time when Lee was talking about building a “metropolis”.

If anyone deserved the mantle of “Singapore’s philosopher king”, it was Raja. He was a man of ideas and action who combined moral philosophy with political power. A deeply philosophical thinker, he was equally at ease pontificating about the ills of a wealth-driven culture, ethnocentrism and xenophobia, as he was about the cures to the diseases that plague dysfunctional democracies and the international order.

As Singapore’s first and longest-serving foreign minister, Raja also came to embody another aspect of Singapore – its distinctive views of the city-state’s place in the world and of the role of small states in international relations.

His efforts to secure Singapore’s sovereignty on the international stage set the direction for the vulnerable city-state’s foreign policy and its approach to international relations for generations to come. He also played an important role in the defining events that shaped the region – the Indonesian Confrontation in the 1960s, the British military withdrawal in the early 1970s, and Vietnam’s invasion of Kampuchea (present-day Cambodia) in 1978. His work makes him a significant figure in the history of Southeast Asia.

At each step of his perilous journey, Raja found himself having to face unexpected dangers and to make critical decisions – some particularly contentious – that would decide the country’s fate. My account of the early years of Singapore’s independence reveals how powerfully “the past” sought to reassert itself, and how dreadful were the dilemmas which confronted the brave souls who took it upon themselves to represent the future. Far-sighted, patient and persistent, Raja forged alliances, sustained the spirits of those around him, and translated the meaning of their struggle into words of force on the international stage.

One would be hard put to invent a foreign minister who could have better guided Singapore’s foreign policy through the dark days following its independence.

There was another vital role he played at a turning point in Singapore’s history, a role which hitherto has been grossly underappreciated. It was his leadership as labour minister during another time of peril – the accelerated British withdrawal in the late 1960s to early 1970s. Raja oversaw the most far-reaching labour reform in the nation’s history and, by doing so, ushered in a new era of industrial relations. He was the political linchpin of a new deal that laid the foundation for a unique tripartite alliance between unions, employers and the government – a system that would prove to be a key competitive advantage for Singapore.

Raja’s story is thus one of trials and also of the triumph of the human spirit. Above all, it is a story of a faith in Singapore – or at least his idea of Singapore – a faith that he clung to until the end.

This is why the dictum in the epigraph to this introduction lurks behind almost every story in this book, even those stories that may not, at first glance, seem to have anything to do with it. Running through all of Raja’s struggles was the common factor of faith: faith not in any god, but in man’s ability to imagine, to create, and to overcome.

That said, Raja did not work alone. And his life, and indeed Singapore itself, would have turned out very differently had it not been for his key allies – most of all Lee, who got him into politics in the first place. As Raja himself said in 1990, he had been involved in many momentous events that he could not have conceived of without Lee in his life. Thus, while this is a book about Raja, it is also one about his closest colleagues, the decisions he made with them, and how he acted when things turned out wrong.

In this connection, one of the most common criticisms of Raja was that he was little more than Lee’s mouthpiece and faithful follower. This book makes clear that Raja was very much his own man with his own views and his own voice. It was perhaps a major contradiction of Raja’s career that he was at once Lee’s loyal lieutenant and a politician beating his own path. It is a tension that is present throughout much of this book.

This biography also brings out the tensions and contradictions that arose as he navigated the complexities of establishing non-communal politics in a multiracial society in an age of “tribal wars”, developing a foreign policy that promoted national interest in a globalising world, and evolving a model of governance and democracy that worked for Singapore in a turbulent region. He was an ardent nationalist and yet a true internationalist who was ahead of his time.

Of course, Raja’s legacy was not perfect. Both in foreign and domestic policy, many of his actions were controversial and remain so. While affable and gentlemanly in person, he could be merciless in combat. The force and clarity with which he expressed his views could crush more sensitive souls. But he always tried to do right by his people and his principles. And while his style of persuasion might not have suited every person or circumstance, it is worth comprehending.

In writing this book, there is one question that I was forced to consider time and again: would Singapore have succeeded without Raja’s involvement in the struggle for its independence, survival and progress?

My answer can be found in the pages of this book.

Suffice to say here that it is extremely hard to see how Singapore would be what it is today without his profound and multifaceted contributions.

But the question has a wider importance, for it asks not only about Raja’s place in Singapore’s history, but also whether the ideas and principles that he championed still have a relevance now and in the future. The answer is not for me to give, but for the people of Singapore, particularly the younger and future generations, to decide.

In his many speeches to young Singaporeans, Raja often reminded them that a nation could determine its own fate, that its people could create the type of society they wanted to belong to and the kind of future they desired for themselves and the nation. “A nation creates its own future – every time and all the time. Nothing is predestined”, he asserted in 1982. “Everything is determined by the will or lack of will on the part of peoples composing a nation. In other words, it is in our hands to choose the kind of future we want.”

It is a great pity that he did not write a book to draw the separate strands of his ideas on nations, nationalism and globalisation; on race, religion and language; and on governance, leadership and democracy to provide a coherent and accessible foundation of his thought, or what might be called “Raja-ism”.

A book was, in fact, on his to-do list. One of his announced plans after his political retirement in 1988 was to write a book tentatively titled From Wanderers to Star-makers. Unfortunately, for reasons explained within these pages, the book never materialised.

But, as its working title suggests, it would be about how transient migrants with their separate languages, religions, cultures and histories – the wanderers – struck roots in new lands and transformed into “star-makers”, people who made their own destiny.

He might not have produced the last major work that many had hoped for, but he stands witness to the truth that, as American journalist Walter Lippmann once said, men are mortal, but ideas are immortal. The name S. Rajaratnam will forever be linked to the resonant words in the Singapore Pledge as well as to the transformative concepts of a “Singaporean Singapore” and “global city”.

In the body of his speeches, he left the basic tenets of Singapore’s foreign policy. After his death, his speeches continued to be read. A good selection can be found in the anthologies, The Prophetic and the Political: Selected Speeches and Writings of S. Rajaratnam, edited by Chan Heng Chee and Obaid ul Haq; and S. Rajaratnam on Singapore: From Ideas to Reality, edited by Kwa Chong Guan.

In honour of his contributions as Singapore’s founding foreign minister, several institutions and initiatives were named after him. In 1998, a decade after his political retirement, the S. Rajaratnam Professorship in Strategic Studies was set up at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies (IDSS) at Nanyang Technological University. Then, in 2007, a year after Raja’s death, the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies was established as an autonomous graduate school and think tank, incorporating the IDSS.

The following year, in 2008, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs launched the S. Rajaratnam Lecture series, an annual event that invites prominent people to speak to the foreign service on topics relating to diplomacy and international relations. In 2014, a S$100 million S. Rajaratnam Endowment was set up by Temasek Holdings to support programmes that foster stronger ties in the region and internationally. And in 2022 – 50 years after Raja’s “global city” speech – the vision, as he articulated it, became the focus of the annual flagship Singapore Perspectives conference organised by the Institute of Policy Studies.

And yet, in all the official and intellectual commemorations of Raja’s life, in all the events and speeches, it is easy to overlook the fire that burned in him throughout his life: the unrelenting conviction that the future is what human beings make of the possible – and the seemingly impossible. It demands from them a creative act. And, like all acts of creation, it will take imagination and ingenuity; patience and pain; and an infinite faith in the power of the human will.

And so we come back to the book that Raja never wrote, about wanderers who become star-makers. My two-volume biography is, in essence, the story of how one wanderer became a star-maker. It is the story of the transformation of a wandering wordsmith into a political giant whose voice reverberates through time.

He was the true Singapore lion who roared, and roared till the end. In a way, it is a perfect metaphor for the life of Raja and the Singapore to which he had devoted that life.

S. Rajaratnam: The Authorised Biography, Volume Two: The Lion’s Roar is written by Irene Ng and published by ISEAS - Yushof Ishak Institute (2024). The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (call nos.: RSING 327.59570092 NG and SING 327.59570092 NG). Irene Ng asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

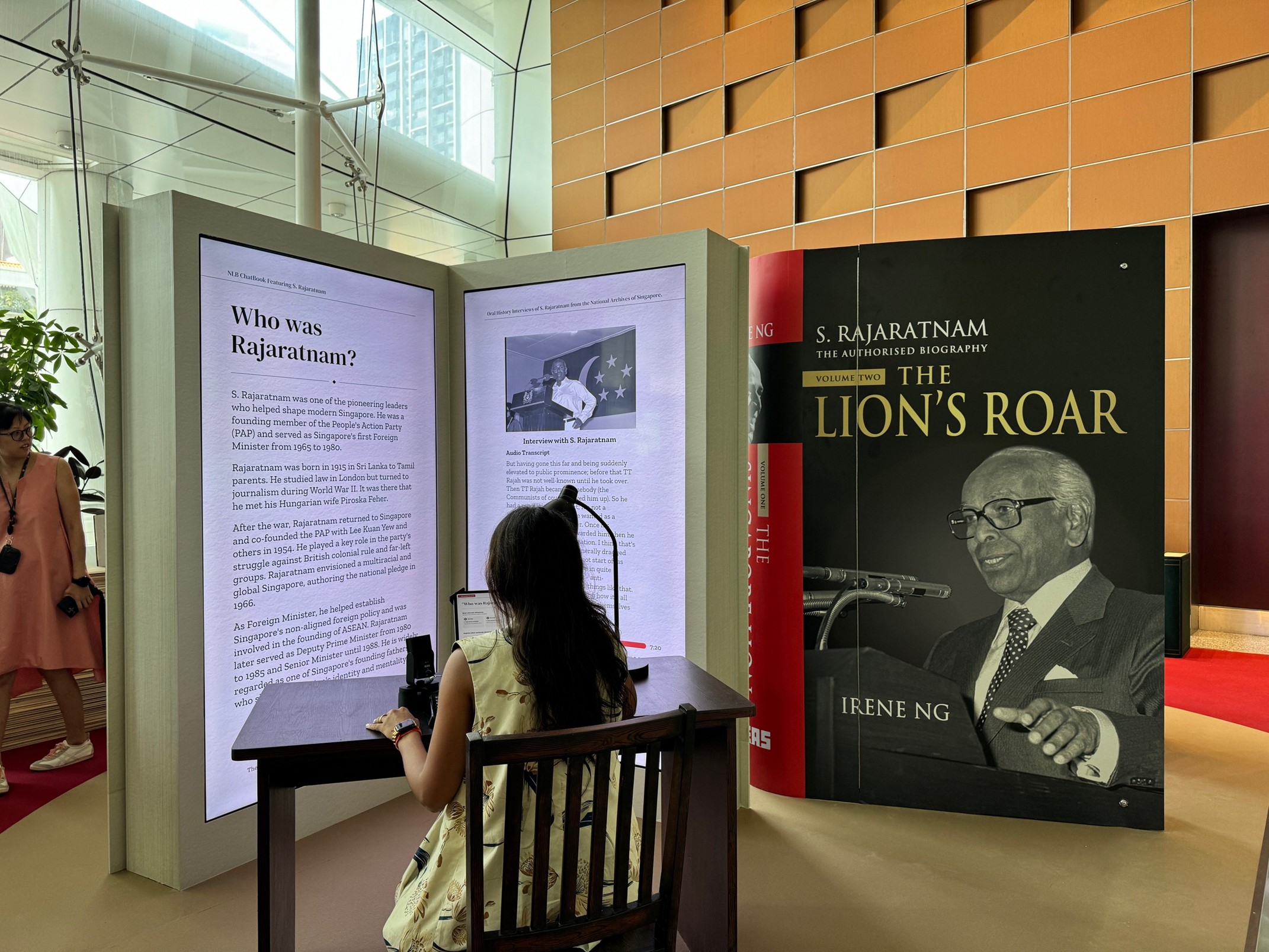

The National Library Board has launched a Generative AI-powered chatbook featuring S. Rajaratnam for users to learn about his life and contributions to Singapore. This service is available at the foyer of the National Library Building from 23 July to 21 Oct 2024.

Irene Ng is the authorised biographer of S. Rajaratnam and Writer-in-Residence at the Institute of ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. She was formerly an award-winning senior political correspondent and a Member of Parliament in Singapore.

Irene Ng is the authorised biographer of S. Rajaratnam and Writer-in-Residence at the Institute of ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. She was formerly an award-winning senior political correspondent and a Member of Parliament in Singapore.Related Articles

Irene Ng, “A Founder’s Literary Legacy: The Short Stories and Radio Plays of S. Rajaratnam,” BiblioAsia 8, no. 1 (May 2012): 4–9.

Irene Ng, “Researching S. Rajaratnam,” BiblioAsia 15, no. 1 (April– June 2019): 42–45.