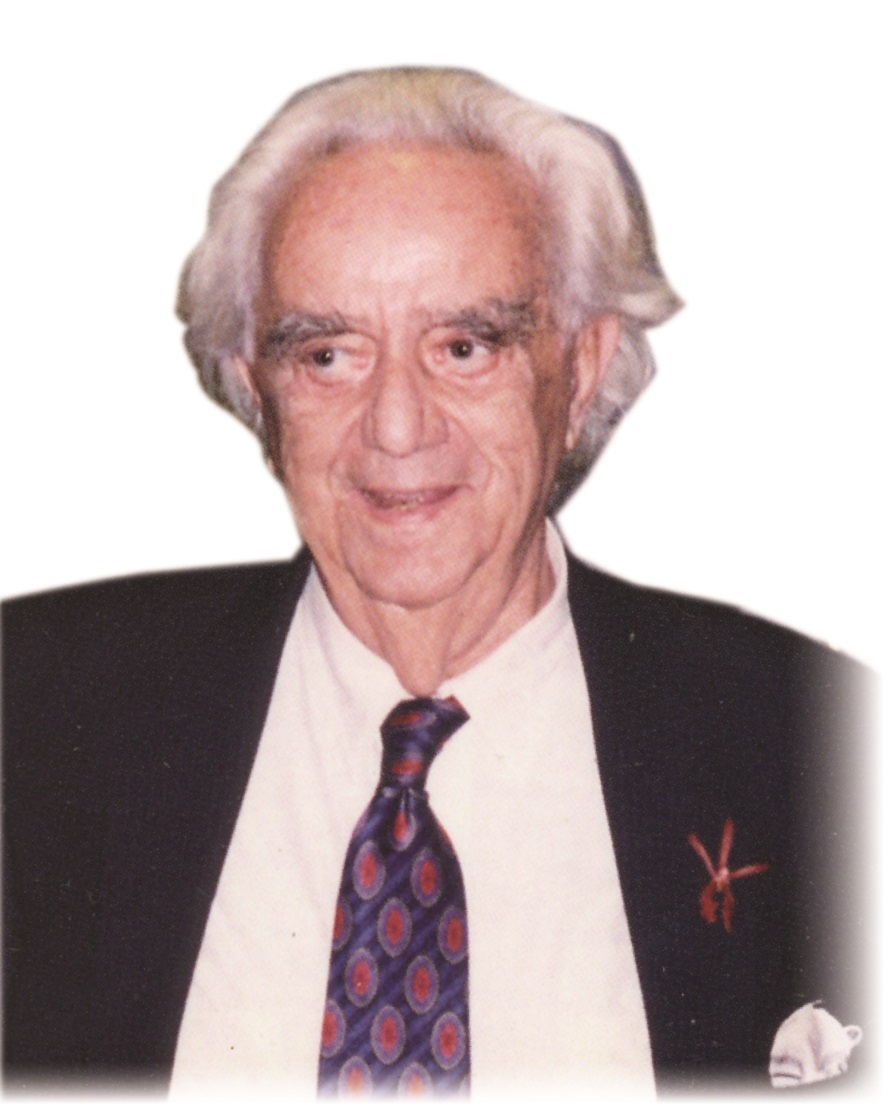

Icon of Justice: Highlights of the Life of David Saul Marshall (1908–1995)

David Marshall became Singapore’s first chief minister in April 1955. He resigned in June 1956, just after 14 months in office, when he failed to obtain self-government for Singapore. In 1978, Marshall was appointed Singapore’s first Ambassador to France, and subsequently to Spain, Portugal and Switzerland.

David Saul Marshall was born in a flat over a Chinese coffin shop at No. 81, Selegie Road, on 12 March 1908, to a Sephardic Jewish family.1 Ambassador Chan Heng Chee described him as a person who is “fired with optimism and purpose”.2 Throughout his illustrious life and career, he made an impact on people’s lives.

Becoming David Marshall

Animal energy, more animal energy and still

more animal energy.3

From a young age, Marshall had shown intolerance towards injustice and discrimination. As a six-year-old child, he punched a Eurasian student when the student called him a Jaudi Jew and demanded that he brushed his shoe. He refused to apologise for the act and was sent off by the teacher to stand at a corner. On another occasion, Marshall witnessed his friend, an American boy dancing an Indian jig and bullying another Chinese student, calling him ‘Chink! Chink! Chinaman!4 Marshall lunged at the American boy and according to him, by the time the teacher pulled them apart, “that cement corridor was streaked with red like a modern painting”.5

As a young child, Marshall often suffered from poor health. Frequent bouts of malaria affected his schooling. However, his drive and determination ensured that he would stay at the top of his class most of the time, earning him the nicknames “Professor Longshanks” and “Professor Lamppost”.6

On the eve of the possibly life changing examination for the prestigious Queen’s Scholarship, he developed tuberculosis and had to pull out of the examination. He was sent off to Switzerland to recuperate. It was during that period of time when he was learning French, that he became inspired by French ideas of equality and justice, prompting him to go through what he termed a “personal revolution” to engage in a lifelong passion for all things French.7

To finance his studies, Marshall did a broad range of jobs: textile representative, salesman selling corks and cars, clerk in a brokerage firm and later in a shipping company.8

Everything was thrown into chaos when the war started. Marshall joined the Singapore Volunteer Corps in 1938 and was later interned as a Prisoner of War during the Japanese Occupation. He was moved from Changi Prison to a camp at Race Course, and then drafted to set sail to Hokkaido, Japan, to work in an industrial area at Hakodate. After that, he also worked in forced labour camps at Yakumo, Muroran, and Nishi Ashibetsu. Together with his fellow inmates, they had to endure hunger, the freezing cold, hardship and cruelty lashed out at them.9 Even during such trying times, he continued to stand up against injustice and ill-treatment, earning the praise of fellow prisoner, Aaron Williams, who remembered that “[even] the sleek and sometimes cruel camp commandant fell for his tactful and persuasive appeals for the betterment of conditions. He was always comforting the sick in our little hospital and by word and deed, he radiated courage and confidence”.10

When Marshall returned to Singapore after the end of the war, he played an active role as the Founder Secretary of the Singapore War Prisoners’ Association. He fought for the interests of the prisoners of war families in their claims for compensation for loss, and for recognition and assistance.

His experience as a prisoner-of-war, facing hard conditions and atrocities, tested his endurance and fighting spirit. It perhaps also shaped his dislike for the death penalty and helped to make him a passionate, humanitarian criminal lawyer. He believed that “[to] take a life is to cheapen human life… it has to be a last resort in extreme cases.”11

Marshall was also concerned with the well being of the Jewish community after the war and wasted no time and worked to set up the Jewish Welfare Board in 1946. He became its first democratically elected president, a position he held for six years. His leadership and contributions to the community won him great respect.

Marshall did not merely care for the Jews residing in Singapore. After his resignation as Chief Minister, he accepted an invitation from China’s People’s Institute of Foreign Affairs for a two month visit from August to October 1956. During this trip, Marshall took the chance from a conversation he had with Premier Zhou Enlai about agreeing to allow the Chinese to spend their last days in China and be buried there, to bring attention to the plight of more than 500 Jews stranded in China who would also like to “join their ethnic group in their spiritual homeland.”12 Majority of these Jews were Soviet citizens caught in the civil war between the nationalists and the communists. Marshall was instrumental in securing exit permits for them to leave China for Israel.

Marshalling the People

I was the midwife of independence.13

The immediate postwar years saw the Southeast Asian countries struggling to gain independence from their colonial masters. Marshall entered politics in the early 1950s to realise his ideal of helping to build a multi-ethnic independent Singapore.

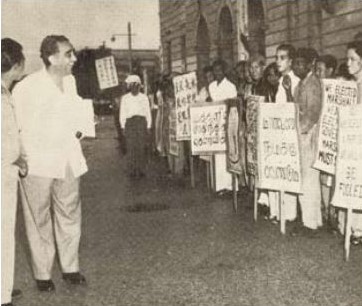

Marshall upheld the values he treasured most: human dignity, self-respect and the freedom to develop one’s potential to the fullest. He wanted Singapore to be “free from the blood-sucking exploitation of racial domination”.14 In the pre-Independence days, the Cricket Club was reserved only for Europeans. Marshall recalled, “I gave them their comeuppance by turning my loudspeakers on to the Cricket Club at lunch time during my campaign for elections under what I called the Old Apple Tree… and lambasted its members for arrogant racism”.15

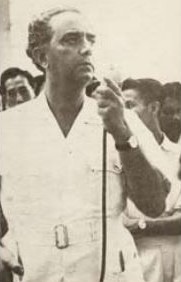

Marshall became Singapore’s first Chief Minister elected under British rule in April 1955. It was not an enviable position. He had to assert his position as Chief Minister among the British, while at the same time face the continuous growth of Malaya’s Communist movements that threatened the stability of the country, numerous violent strikes and demonstrations, and the lack of food, resources, housing and jobs.

Honouring his promise, Marshall resigned in June 1956, just after 14 months in office when he failed to obtain self-government for Singapore during the first constitutional negotiations with the British government. However, he continued to be active in politics until 1963 when he lost in the Legislative Assembly General Elections, during which he campaigned as an independent candidate in the Anson constituency.

Even though he did not manage to follow through a number of the good ideas he supported or introduced during his years in politics, the People’s Action Party subsequently translated some of these ideas into policies. Some of the policies include the creed of multilingualism and multiracialism, an education policy for nation building, and the Central Provident Fund.

During his tenure as Chief Minister, Marshall introduced a weekly “Meet the People” session to close the gap and enhance understanding between the Civil Service and the people. His attempt to bring the government closer to the people prompted the Singapore Tiger Standard to comment on 30 October 1955, that “[it] can be safely said that [in] the past six months the government has learnt more about the people’s problems than in the past years”.16 To this day, the government still uses similar sessions to gather feedback from the grassroots.

Marshall credited Tan Lark Sye for emphasising to him, the issues of Chinese citizenship and multilingualism.17 Mainly because of that, multilingualism in the Assembly and parity of multilingual streams of education were introduced. During Marshall’s China trip in 1956 after his resignation as Chief Minister, he sought and obtained clarification from Premier Zhou Enlai on the issue of nationality of the Chinese in Singapore. Premier Zhou explained that the Chinese Government was keen to engage in a friendly relationship with Southeast Asia, and that the Overseas Chinese “should adopt the nationality of their country of residence”.18 Hence, 220,000 China-born Chinese residents were given a choice of accepting the offer of Singapore citizenship.

Passionate Defender for the Underprivileged

In court I am afraid neither of God nor of the devil.19

Although he would have preferred to study medicine and psychiatry, Marshall decided to study law in 1934 due to financial constraints. After returning from his studies in England, he was called to the Bar in February 1938. Within a year, he had established himself as a promising lawyer.

In a career that spanned 41 years; Marshall was an inspiration to others. He defended a wide range of criminal cases: armed robbery, corruption, drug trafficking, forgery, fraud, murder, rape and tax evasion. Alex Josey’s The David Marshall Trials highlighted some of the sensational trials he was involved in. Marshall once said that he went into criminal law because he felt that was where fellow citizens were most vulnerable. Marshall felt that if they could go to someone whom they had faith in, they would feel comfortable, so that even if they were to lose the case, they would feel that they had “somebody to protect them….”20

Marshall was always prepared for his day in Court. With just five hours of sleep, he would ask the telephone company to wake him up at 2am. Then in the quiet of the night, he would work through his case and arrive in Court at 8.30am. His dedication and commitment to each case made his opponent work just as hard. In a speech given during a fundraising dinner, Professor Tommy Koh, Ambassador-At-Large and Marshall’s former student recalled “the sight of young prosecutors cringing at the sight of the legendary David Marshall waiting to eat them for breakfast”.21

Supreme Court judge Justice M.P.H. Rubin recalled, “I don’t think I have ever seen anyone as good as Mr Marshall or even close to him.”22 Lawyer Harry Elias said in a tribute to Marshall that he was “[as] a man, a giant. Robust in his love for life, compassionate as a champion for the underdog. As a lawyer, a beacon. Everybody wanted to be a David Marshall. He was the last of his kind.”23 Marshall retired from the Bar at the age of 70 in 1978, on being appointed as Singapore’s first Ambassador to France.

Marshall received numerous honours and awards for his work in the legal profession. He became an Honorary Member of the Law Society in December 1978. In recognition of his contribution to the legal profession, he was conferred Doctor of Laws Honoris Causa by the National University of Singapore in September 1987. He received the highest honour bestowed by the legal profession, when the Singapore Academy of Law made him an Honorary Member and Fellow for Life in 1992. To honour his outstanding contribution, the National University of Singapore’s Law Faculty set up the David Marshall Professorship in Law in June 1993. A total of S$1.5 million was pledged within a short period of one and a half years.

After his distinguished achievements as an Ambassador for 15 years from 1978 to 1993, Marshall continued his connection with the legal profession by becoming a consultant to the established law firm, Drew and Napier in October 1993. He embraced his new post with enthusiasm, saying that it gave him a new lease in life.

Service for the Country

I have been in the wilderness for more than 20 years and

I ached to serve my country.24

At the age of 70 in May 1978, Marshall was appointed as Singapore’s first Ambassador to France, and subsequently, also to Spain, Portugal and Switzerland. He was well-known as the Ambassadeur a orchidée (the Ambassador with an orchid) as he would wear an orchid on his lapel at every official function.

Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong recalled that, as Ambassador, Marshall would drop him notes occasionally on ideas that he believed Singapore could adopt. These notes demonstrated “his deep love for Singapore and desire for Singapore to do well”.25

He retired 15 years later due to deteriorating eyesight. The then Senior Minister Lee Kuan Yew praised him for carrying out his duties with zeal and vigour. His enthusiasm, charisma and drive resulted in strengthening Singapore’s relations with the French. The number of French firms in Singapore was said to have increased from 180 to more than 400 during his tenure as an Ambassador.26

In France, Marshall was well known and popular. In recognition of his humane work and service, he received France’s highest award, the Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur in 1978.27 While in 1989, he was given the honour of lighting the flame beneath the Arc de Triomphe in an event to commemorate the end of World War I. Since 1923, the French war veterans have lit the flame daily to pay tribute to those who fought and died for their country in past wars.28

In 1990, he was awarded the Meritorious Service Medal in recognition of his immense contributions to the progress of Singapore.

Thoughts for Singapore

Despite the blemishes,

I consider myself lucky to be a

Singaporean.

It’s like winning a major lottery

in life.29

Marshall never stopped showing concern for the development of Singapore. Prior to Singapore’s independence, he was vocal in expressing his views on the British colonialists and challenged the boundaries set by them whenever he could. Well-cited examples include the use of green ink in retaliation of being told not to use the red ink that was reserved for the Governor, and wearing a bush jacket to important functions instead of formal clothing. He wanted Singapore to be run by her own people, with their own protocol. He tirelessly shared his dreams of Singapore gaining independence with the people.

In the later years when he was no longer politically active, Marshall continued to express his thoughts on improvements that could be made in Singapore. They consisted of a broad range of issues. He was upset about the high legal fees charged by lawyers as he believed that the legal profession was a calling and not money-making business.30 He did not agree with the Maintenance of Parents Bill; he felt that it was important to have a jury system; and he was always against the death penalty and caning.

Marshall was disturbed by the show of political apathy among Singaporeans, the lack of constructive criticism, the lack of press freedom, and widespread demonstration of materialism. He also felt that it was important to have a loyal and honest Opposition in Singapore, and argued, that “the duty of an [Opposition] is to respect, to praise and to encourage valuable contributions by the government to the welfare of the country, and to criticise where the government is flat-footed or fails”.31

Marshall was proud of what the government had done within a short span of time. In an incident that happened during his ambassadorial tenure, he tried for 10 years to persuade Madrid to allow SIA to fly there. He was successful in persuading people along the line of authority till he reached the international relations vice-president of Air Iberia. His reason for refusal was that the Singapore Airlines was “ruthlessly efficient”. Marshall thought it was a “lovely phrase” which showed how much the country has progressed since Independence.32

When asked about his thoughts on Singapore’s economic situation in 1994, Marshall said the he was “in awe of the economic and social growth… in the last 40 years” and felt that the “administrative and good sense of the government is astounding”.33 Reflecting upon his time as Chief Minister, he felt that he “would never have been able to achieve what the PAP have achieved pragmatically” and added that he would have perhaps “sought to give a human face to their remarkable pragmatic achievements”.34

In an interview published in Asiaweek, Marshall added that the government lacked “a feeling for the human spirit and the development of the graces of living, the development of the human mind” but he was optimistic that Singapore would achieve her potential of becoming a “lighthouse in Southeast Asia”, though he said he might not live to see that day.35

Joy for Living

I see life as a miracle of joy.36

When interviewed about places in Singapore that held special memories for him, Marshall shared that the Botanic Gardens was a place where he used to visit with his family as a child. The family used to have picnics there and enjoyed tea and ice cream from a tea kiosk.37

As a result of his love of art, the Botanic Gardens today owns three beautiful bronze sculptures, which are gifts from Marshall. He commissioned British sculptor Sydney Harpley to create: Girl on a Swing (1984), Girl on a Bicycle (1987) and Lady on a Hammock (1989). According to his wife, Jean Marshall, he “gave the three statues… to the people of Singapore because anyone looking at them will [smile and] feel the excitement and joy of living”.38

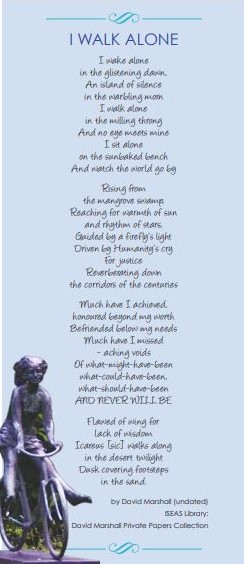

On his 84th birthday, Marshall shared his philosophy in life which was best expressed in his own words, “… You’ve got to learn to take the risks of barking your shins and breaking your bones in order to achieve anything. You’ve got to take risks in life. You can’t put yourself in a crystal coffin and be fed by intravenous injections”. He also had two principles in life: the first, the more you give of yourself, the more you grow and the second, he preferred a bleeding heart to a frozen one.39

In retrospect, David Marshall was a man who lived his life with passion. On 12 December 1995, he succumbed to lung cancer and passed away at the age of 87.

The author would like to thank Mrs Jean Marshall for reading her draft and offering suggestions for improvement. She is also most grateful to Dr Kevin Tan for his words of encouragement.

NOTES

-

Mindy Tan Huimin, The Legal Eagle: David Marshall (Singapore: SNP Editions, 2008), 8. (Call no. RSING 959.5705092 TAN) ↩

-

Chan, Heng Chee, A Sensation of Independence: David Marshall, a Political Biography (Singapore: Times Books International, 2001), 26. (Call no. RSING 324.2092 CHA) ↩

-

Margaret Thomas, “The Lion in Winter,” Business Times, 6 June 1992, 3. (From Newspaper) ↩

-

Dharmendra Yadav, “Meeting David Marshall in 1994 - An Interview with Dr David Marshall,” Singapore Law Gazette (November 2006): 13. ↩

-

John Lui, “He Pulled No Punches”, Straits Times, 10 October 1993, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Goh Hwee Leng, “Marshalling the People”, Singapore Tatler (March 1991): 120. ↩

-

M.G.G. Pillai, “Singapore’s Own Marshall Plan”, Asiaweek 4, no. 43 (3 November 1978) 36. ↩

-

Goh, “Marshalling the People”, 120; Serene Lim, “I Had Wanted To Be a Doctor, Says Lawyer-Ambassador Marshall,” Straits Times, 4 May 1992, 24. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chan, Sensation of Independence, 50–52. ↩

-

Edmund Lim W.K. and Kho Ee Moi, The Chesed-El Synagogue: Its History and People (Singapore: Trustees of ChesedEl Synagogue, 2005), 85. (Call no. RSING 296.095957 LIM) ↩

-

“‘I Did Not Compromise My Politics To Be Envoy’,” Straits Times, 28 October 1978, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

David Marshall, Letters From Mao’s China; Edited With an Introduction by Michael Leifer (Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society, 1996), 35. (Call no. RSING 951.05 MAR) ↩

-

Laure De Gramont, “For David Marshall’s Election as Chief Minister the Tangling Club Covered Itself With Black Crepe,” Vogue Paris, no. 741 (November 1993): 4. ↩

-

David Marshall, “Among the Greatest Gifts Is Dignity,” Straits Times, 9 August 1990, 21. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Irene Hoe, “The People’s Padang,” Straits Times, 9 August 1993, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ronnie Duclos, “Closer Harmony Between People & Govt,” Sunday Standard, 30 October 1955, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

David Saul Marshall, Singapore’s Struggle for Nationhood, 1945–59 (Singapore: University Education Press, 1971), 11. (Call no. RCLOS 959.57024 MAR) ↩

-

Chan, Heng Chee, A Sensation of Independence: David Marshall, a Political Biography (Singapore: Times Books International, 2001), 210. (Call no. RSING 324.2092 CHA) ↩

-

Margaret Thomas, “Vintage Marshall,” Business Times, 6 June 1992, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“In Conversation: An Interview With Dr David Marshall,” Singapore Law Review, no. 15 (1994): 1–2. ↩

-

“In Memorium: A Tribute to the Late Mr David Saul Marshall,” Singapore Law Review, no. 17 (1996): 20. ↩

-

Elena Chong, “Justice Rubin Retires After 14 Years,” Straits Times, 5 February 2005, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Susan Sim, “Tribute to David Marshall,” Straits Times, 13 December 1995, 27. (From NewspaoerSG) ↩

-

“Marshall, A Welcome Posting,” Far Eastern Economic Review, 17 November 1988, 8. ↩

-

Anna Teo, “One of the Most Remarkable Men S’pore Produced,” Business Times, 13 December 1995, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Yusman Ahmad, “For a More Humane Land: David Marshall Expresses His Thought to Better Singapore,” Malaysian Business, 1 April 1994, 56. ↩

-

Joan Bieder, The Jews of Singapore (Singapore: Suntree Media, 2007), 132. (Call no. RSING 959.57004924 BIE) ↩

-

Tan Lian Choo, “Marshall Lights Flame at Paris Memorial,” Straits Times, 6 August 1989, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ahmad, “For a More Humane Land,” 59. ↩

-

Chiang Yin Pheng, “Marshall – Law a Calling, Not Money-Making Business,” Straits Times, 24 February 1995, 31. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Thomas, “Vintage Marshall.” ↩

-

Thomas, Margaret, “Flying the Flag in France,” Business Times, 6 June 1992, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ahmad, “For a More Humane Land,” 59. ↩

-

Thomas, “Vintage Marshall.” ↩

-

“The Lion in Winter: A Founding Father Calls for Greater Openness,” Asiaweek 20, no. 14 (6 April 1004, 28. ↩

-

Tan Sai Song, “Embrace Marshall’s Legacy: His Passionate Love of Life,” Straits Times (Overseas ed), 23 December 1995, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan, Sumiko, “Places of the Heart”, Straits Times, 9 August 1989, 18. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“In Memorium,” 50. ↩

-

Thomas, “Vintage Marshall.” ↩