Selected British Colonial Era Overseas Chinese Personalities and Their Links to to Communities

Introduction

The beginning of the 1915 century saw mass immigrations from mainland China. There were the “push” factors such as internal wars, famines and starvation, corruptions and struggles for power within the Qing courts on one side and on the other side, the “pull” factors of jobs and wealth opportunities in the Southeast Asian region under the British rule.

In this paper, we will discuss the migration of mainland Chinese into the British colonies in Southeast Asia with focus on Rangoon,1 Penang and Singapore.

The three cities were integrated during the British rule. Some road names are common; for example, “Armenian Street” and “Beach Road” are found in Penang and Singapore. There are also Burmese street names such Irrawaddy Road, Mandalay Road and Rangoon Road in Singapore and Jalan Burma in Penang.

The stories of Chinese entrepreneurs selected for this commentary showed how some humble mainland Chinese ventured into regions beyond their imagination. They had no financial means or assets but prospered in the second homeland, becoming leaders in their own right. Many left legacies which remain till today.

Penang, Malaya (1786)

This was the first of the British trading outposts in Southeast Asia when Captain Francis Light, a British naval officer and trader for the British East India Company, sailed into George Town Port on 17 July 1786 with a fleet of three naval vessels comprising a small civilian team and some naval staff. Penang became the first base for the company in Southeast Asia.

It was recorded that most of the inhabitants in Penang then were indigenous Malays and a sizeable community of some Chinese had already settled there prior to the British arrival.

Singapore (1819)

In 1819, Sir Stamford Raffles landed on the shores of Singapore (then known as “Temasek” and later “Singapura”) with an offer to the island’s local rulers for a British factory to be established there. The offer looked too good to refuse as the island was then only a fishing port. Singapore soon grew to become the most important British colony and strategic trading post.

One of the reasons cited for this success is its geographically strategic and deepwater seaport position. The territorial separation from the Malayan Peninsula also made it an ideal and easy port of call for the merchant navies from East and West.

Together with Penang and other Straits Settlements territories, Singapore came under the direct administration of the East India Company from 1819–1867. In 1867, Singapore attained the status of Crown Colony asserting dominance over the affairs of the region.

Singapore retained the premier position as the seat of administration for the British colony until Rangoon was added to the Crown Colony in 1885. However, to this very day, Singapore remains a strategic entrepot and the Asian cross-road between the East and the West.

Rangoon, Burma (1885)

It all began when the British launched the Second Anglo-Burmese war in 1852, seized control of Lower Burma and then transformed Rangoon into a commercial centre and political hub for British Burma.

During the peaceful and economically stable years in Southeast Asia under the British rule, more mainland Chinese ventured out and most landed in Rangoon where jobs and opportunities were in abundance. The Irrawaddy Delta region then referred to as the “Rice Bowl of Asia” received most of the migrants.

British Rangoon, with its spacious parks and lakes and mix of modern buildings and traditional wooden architecture, was then also known as “the garden city of the East”. It was recorded as the most prosperous city in Southeast Asia. Towards the early 20th century, Rangoon had public services and infrastructure on a par with the City of London.2

Trade and Commerce

After Britain restructured its crown colonies following the annexation of Burma, the Southeast Asia region became stable. Trade and commerce grew. Trading of rice and other staple food and commodities, especially teak wood from Burma, led the growth. Shipping became the essential transportation and communication infrastructure for the region.

Many shipping. lines were established to transport people and goods.3

Carriage of goods by sea complemented overland transportation modes. It was a faster option. A single journey, for example, from Rangoon to Singapore that would have taken months could be shortened to weeks by the sea-route.

The shipping industry helped to fuel the growth of commerce and communications, expanding trade within the region and China. However, control of trade and commerce still rested with the British and Europeans merchants and traders as they enjoyed preferential treatments and could influence the British Administrators.

The Burmese Overseas - Chinese Shipping Tycoon Lim Chin Tsong (1867–1923)4

Lim Chin Tsong (LCT), a Rangoon-born Chinese merchant, became an important intermediary of the Burmah Oil Company.5

His father, Lim Si Xing, a rice merchant, came from Tong An County in Fujian Province, China, in 1861 and settled in Rangoon. When conducting businesses with the British and Europeans, due to a lack of understanding in the English language, the elder Lim found himself handicapped. He therefore sent his son to St. Paul’s College, then a premier English school in Rangoon. It was this education that laid the foundation for LCT and equipped him in his later years.

LCT operated his business from an office in China Street, Rangoon.6 He had a network of oil distributors which extended throughout British Burma.

With some ocean-going vessels: SS Glenogie, SS Seang Bee, SS Seang Choon, SS Seang Kok, SS Seang Lee, among others, LCT established his Seang Line of Steamers (“The Chinese Steamship Company of Rangoon”) plying from Rangoon to Singapore, Penang, Hong Kong, Swatow and Amoy (Xiamen).

Kim Keng Leong & Company (Chop Kim Cheong), Penang, was the agent for Seang Line. Soo Bee Kongsi (Rangoon Kerosene Oil), Ooi Saik & Company (Rangoon - Penang rice merchants) were also agents for LCT located at 127 Beach Street, Penang.7

Seang Line Singapore agency was vested with Giang Hoe Company which was first located at 64 Japan Street (now called Boon Tat Street),8 Singapore. It later moved to 129 Cecil Street, Singapore.9

As a result of his shipping line and the growth in trade and commerce, LCT prospered and his influence grew. He became a member of the legislative council and was awarded the Order of the British Empire (OBE) by the British Throne.

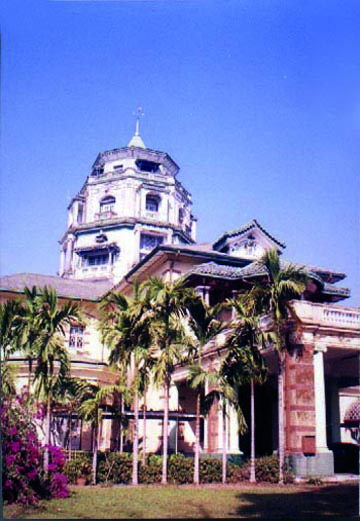

In Rangoon, he built a palatial residence in one of the affluent quarters of Rangoon. It is shaped like a star and furnished with mural paintings. “Xie De Garden”, as it was known, was graced by many rich and influential personalities and foreign dignitaries during that time.

The palace, still standing today, was home to former Burmese presidents and ministers. It is currently occupied by the Ministry of Culture.

As Agent for Burmah Oil Company (BOC) 10

At first, LCT’s exclusive agency with BOC got the British managers, seated at their control office in Glasgow, Scotland, gratified at having such an energetic man in full control of their kerosene sales. However, he lacked financial management ability, which became his downfall. His accounts were reported to be in such a mess that personally, LCT did not even know how much he owed and what his profits were. All he knew was that he was cash-rich.

From 1908 onwards, after being awarded the agency for the company’s product sales in the province, he became a serious bad paymaster to Finlay Fleming & Company, BOC’s managing agent in London, for the purchases he made. By the beginning of 1911 he reportedly owed several hundred thousand sterling pounds.

Apparently, as it was later found out, the transactions from all his different business activities were jumbled up. He was managing steamships and a match factory, rubber plantations and tin mining without keeping a proper audit of the transactions. It became impossible to distinguish where one account ended and another began. In those days, there were also no auditors.

Before the managers could terminate his services, LCT had resigned and was outside Burma. He had taken over one of his own ships, the SS “Seang Bee”, to fulfill a lifetime’s ambition to visit London together with his family, friends and business associates; a trip that was crazy enough to inspire an ironic comment (would be good to quote that ‘comment’) due to his mounting debts. But, in reality, he recouped his expenses from the cargoes the liner carried.

In London he called on David Sime Cargill and other directors, who entertained him and his party at the Hyde Park Hotel. All business talks were carefully avoided until a formal meeting was later held in the office. A generous final settlement scheme was finalised and they parted in complete amity.

In November 1923, at the age of 53, LCT reportedly died from a heart attack when the telephone company threatened to disconnect his telephone line for non-payment and aggravated by an untimely and unwelcome “communication” from his bank.

At first, LCT’s exclusive agency with BOC got the British managers, seated at their control office in Glasgow, Scotland, gratified at having such an energetic man in full control of their kerosene sales. However, he lacked financial management ability, which became his downfall. His accounts were reported to be in such a mess that personally, LCT did not even know how much he owed and what his profits were. All he knew was that he was cash-rich.

From 1908 onwards, after being awarded the agency for the company’s product sales in the province, he became a serious bad paymaster to Finlay Fleming & Company, BOC’s managing agent in London, for the purchases he made. By the beginning of 1911 he reportedly owed several hundred thousand sterling pounds.

Apparently, as it was later found out, the transactions from all his different business activities were jumbled up. He was managing steamships and a match factory, rubber plantations and tin mining without keeping a proper audit of the transactions. It became impossible to distinguish where one account ended and another began. In those days, there were also no auditors.

Before the managers could terminate his services, LCT had resigned and was outside Burma. He had taken over one of his own ships, the SS “Seang Bee”, to fulfill a lifetime’s ambition to visit London together with his family, friends and business associates; a trip that was crazy enough to inspire an ironic comment (would be good to quote that ‘comment’) due to his mounting debts. But, in reality, he recouped his expenses from the cargoes the liner carried.11

In London he called on David Sime Cargill and other directors, who entertained him and his party at the Hyde Park Hotel. All business talks were carefully avoided until a formal meeting was later held in the office. A generous final settlement scheme was finalised and they parted in complete amity.

In November 1923, at the age of 53, LCT reportedly died from a heart attack when the telephone company threatened to disconnect his telephone line for non-payment and aggravated by an untimely and unwelcome “communication” from his bank.

Media and Newspapers

When the shipping industry grew, it facilitated growth of the media, in particular, the newspapers. Several papers were established and these were meant to meet the needs of the Chinese communities which had grown in numbers. The overseas Chinese wanted to become more informed on the happenings in their regions and to foster communication links with the communities at large.

The newspapers also played important roles in maintaining communication links and educating the then migrant communities about their establishments such as the formation of clan houses where the new arrivals and impoverished migrants, who had fallen on hard times, could seek help from.

Many who had lost communications with their families in the mainland could also publish their news. The newspapers became links for lost relatives.

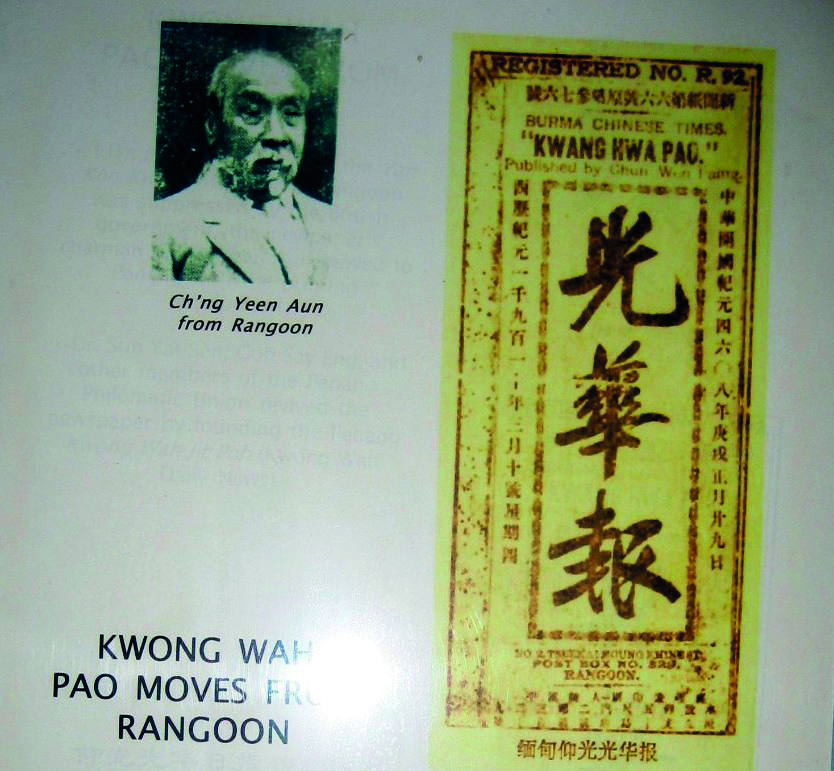

The World’s Oldest Chinese Newspaper - Kwang Wah Yit Poh12 Ch’ng Yeen Aun (1867–1938)13

He was founder and Chairman of the Rangoon and Penang Kwong Wah Jit Poh,14, one of the surviving oldest Chinese language newspapers.

He was born in Ouan-zhou village, Tong An County, Fujian Province, China. He migrated to Burma at the age of 18. At first, he stayed in a village in Lower Burma working as a paddy farmer. He later moved to Rangoon and set up “Chop Guan Kee”, a grocery shop.

In 1904 he met Kang You-wei,15 a Royalist from the Qing Court in Rangoon when Kang visited Burma. Kang persuaded him to establish a base for the “Bao Huang Hui”16 in Rangoon Chinatown.

In May 1905, Qin Li-shan, a Hunan-born Revolutionist, also visited Rangoon to spread the China Revolutionary ideology. Qin met with Ch’ng and exposed Kang’s scheme to preserve the Qing’s throne. Kang’s selfish ambition was to stage a revolt against the Empress Dowager Cixi using the powerless Emperor Guangxu to assume control of the Chinese court.

After meeting Qin, Ch’ng abandoned the “Bao Huang Hui” and joined the Tung Meng Hui in Rangoon.

Kwang Wah Jit Poh and Tung Meng Hui

In August 1908, Ch’ng Yeen Aun, Xu Zang-zhou and other overseas Chinese in Rangoon raised funds to set up Tung Meng Hui’s political mouthpiece and called it “Kwong Wah Jit Poh”, a name preserved to this very day. Ch’ng became Managing Director of the newspaper. He was able to spread revolutionary thoughts through various articles published in the newspaper. Dr Sun Yat Sen also recommended Ju-zheng, Yang Qiu-fan and Lu Zhi-yi as principal editors to assist Ch’ng.

On 20 November 1908, Tung Meng Hui Burma branch held its inaugural meeting at Rangoon. Ch’ng Yeen Aun was unanimously elected by overseas Chinese in Burma as Chairman.17 Ch’ng quickly set up sub-branches in the main cities of Burma. In recognition of his active achievement Dr Sun Yat Sen personally wrote him a letter to express his delight and approval.18

The British however raised their objections to the political contents of the newspaper and the involvement of Tung Meng Hui. As a result of this, Ch’ng packed up his operations in Rangoon and moved over to Penang where the newspaper remains to this very day.

The Chinese Patriot and Nanyang Siang Pau19 Tan Kah Kee20 (1874–1961)

Much had been written about Tan Kah Kee as an entrepreneur and philanthropist who played a major role in the establishing of schools and universities to educate the young. The Chinese newspapers in fact played very central roles as the means for communication in the days before the proliferation of the radio and television as seen in the case of Kwang Wah Jit Poh.

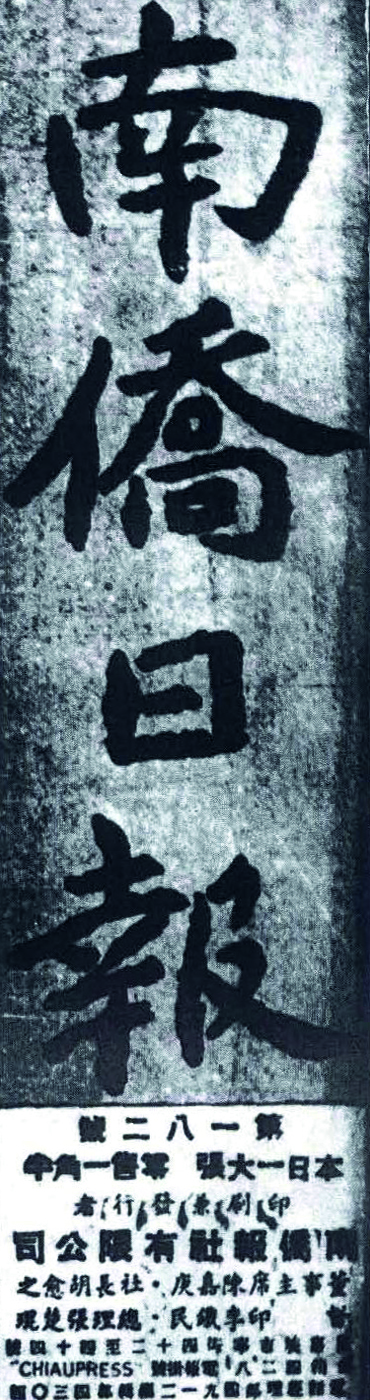

Tan Kah Kee (TKK) was instrumental in the establishing of Nanyang Siang Pau, a major Chinese daily, on 6 September 1923 in Singapore. Nanyang Siang Pau reportedly became one of the most influential commercial Chinese newspapers in Southeast Asia.

It was reportedly the first commercial Chinese newspaper in Singapore and its influences was felt throughout Southeast Asia as well as China. The Chinese daily newspaper was distributed in Penang by Khiam Aik (Penang Branch) and in Rangoon jointly by Tan Kah Kee & Company (Rangoon Branch) and Aw Boon Haw’s Tiger Balm Rangoon office.

In 1932, however, he lost control of Nanyang Siang Pau and the paper was acquired by his son-in-law, Lee Kong Chian. It was then merged with The Sin Kok Min Press.

Early Days and the Setting Up of Business Enterprises

In 1890, at the age of 17, TKK came to Singapore and worked at Chop Soon An,21 a sundry shop and rice trading firm, owned by his father. He learned the trade and ventured out on his own when he was 30 years old.

During the time when he worked at Chop Soon An, his father taught him the rice importing trade. Rangoon, during the British Burma administration, was known as the “Rice Bowl of Asia” and rice grown there was exported to Singapore via Penang which was also under the British administration. He later diversified his operations further into pineapple and rubber.

He tried his hands at growing pineapple which was harvested and canned under his own brand “Sin Lee Chuan”. He became successful in the pineapple canning business and was acknowledged the “Pineapple King”.

He reportedly invested about $2,000,000 (Straits currency) in a rubber planting business and jointly set up the Khiam Aik Rubber Processing Factory with Penang Rubber Company. Khiam Aik was based in Penang.

Tan Kah Kee & Company had three other branches in Rangoon; one in the main capital of British Burma and one each in two other cities - Bassein (situated in the Irrawaddy Delta) and Mandalay (where the Royal Palace is located). At its prime, Tan Kah Kee & Company had a total of about 70 branches in Southeast Asia and elsewhere.

However, when the Depression crept into Asia, his fortunes declined. In 1937, Tan Kah Kee & Company had to fold up.

The Prominent Chinese Patriot

Through Nanyang Siang Pau and his business enterprises, TKK displayed his Chinese patriotic spirit when he was actively involved with the Tung Meng Hui-Nationalist movement under Chiang Kai-shek. He was a member of the Tung Meng Hui in 1910 and his network of influence, besides mainland China, was spun around the region in Singapore, Penang and other parts of Malaya and Rangoon.

However, he was disillusioned with the rampant corruptions within the ranks of the Chiang Kai-shek movement. He later switched camp to support Mao Tzu-Tung’s Chinese Communists Party.

TKK was a man who would not give up without a good fight. He loved literature and he understood the strength of the media and the written word. During the period 1946–1959, after losing control of Nanyang Siang Pau, he took control of Nam Kew Poo and developed the paper into an equally influential media. He reportedly wrote many of the articles in Nam Kew Poo to pursue his political campaigns against Chiang Kai-shek.

Among the many articles he wrote in Nam Kew Poo, were famous headline articles: in chinese.

He was relentless in his efforts to establish links with the overseas Chinese. For about nine months in 1940, he led the China Comfort Team from Nanyang and travelled throughout mainland China visiting no less than 15 provinces. The China Comfort Team was from the China Comfort Mission, which comforted the wounded and assessed the war conditions in China. Its leader Tan Kah Kee represented both the Singapore and the Southseas China Relief Funds. Among the other regions he travelled to were Mandalay and Rangoon in Burma, which was at the Yunnan border. The Chinese communities in Burma warmly welcomed him. He was reportedly a very charismatic speaker who could captivate an audience for more than three hours.

It was reported that on 22 December 1940, when he was in Penang, he met up with Wu Tie Cheng, a special envoy of the Kuomingtang Government, whose mission was to dissuade TKK from the Chinese Communist ideology. He firmly held his ground.

On 30 March 1941, TKK presented a reportedly powerful public talk at the Second Nanyang Cities Representatives Meeting attended by the Singapore and Malaya overseas Chinese communities. The speech was published in the Chinese newspaper (chinese newspaper) in Penang.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War (7 July 1937–9 September 1945), TKK was regarded as one of the prominent ethnic Chinese Malayans who provided financial support for the Chinese resistance efforts in the mainland. He organised many relief funds under his name and that made him a target sought by the Japanese. When the Japanese landed in Singapore he fled to Java, Indonesia. There, he was protected and housed by many friends and past business associates and their families. While he was in Java he penned his two-volume autobiography, “Nan-qiao-hui-yi-lu”.22

TKK’s most famous charitable work was founding Xiamen University, which he privately funded until 1936. His grandchildren commented that he left no inheritance for them and even took out personal loans to fund the operations of the university for 16 years, an act of sacrifice that is recognised and honoured even to this very day.

Besides Singapore, TKK had a very strong influence on the Chinese communities in Penang, Burma, several southern China cities and Hong Kong. When he passed away in 1961, the communities held memorial services to honour the man who had made a difference in their lives.

Banking

When shipping and commerce grew, banking naturally developed alongside to provide the monetary support activities. Initially, banking activities were confined to foreign exchange and remittance services which catered for the traders paying their suppliers and sellers of commodities and also for the migrants who wanted to remit monies to their homes in the mainland.

Banks eliminated the risks of losing some hard-earned monies to robbers if the traders or migrants had carried gold and silver or cash. One could just deposit funds in one branch and then cable instructions to the other branch to pay to the order of a certain party in that country or locality. The creation of the Straits Dollars in the 1898 provided a uniformed monetary system managed by the banks to facilitate trade and commerce.

From the seat of government of the British Crown Colony in Rangoon, several banks were formed. Some of the names of banks remain to this very day but others were merged, bankrupted and driven out of business.

Enterprising Businessman, Banker, Patriotic Chinese and Philanthropist Tan Ean Kiam23 (1881–1943)

Born in China’s Tong-An County, Fujian Province in 1881, Tan Ean Kiam came to Singapore with his father when he was 18 years old. He started out as a general worker and later ventured into business on his own. He became a successful businessman and merchant, and later as one of the first managing directors of the Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation Limited (OCBC), currently Singapore’s third largest bank that is publicly listed on the Singapore Exchange.

The Businessman and Banker

In 1908, Tan Ean Kiam set up Chop Joo Guan where he traded in rubber commodities which became very highly priced because transportation became difficult in World War I. His rubber trade became lucrative, providing him with handsome profits.

With the money he made from rubber, on 28 June1919, he formed the Oversea-Chinese Bank Limited (OCBC),24 one of the component banks of today’s OCBC, with Oei Tiong Ham,25 then known as “Sugar King” of Java, who subscribed a total of $1,000,000 (Straits Dollars) as the starting capital.

The bank unexpectedly fell short of liquid cash and so, to increase their capital, Tan Ean Kiam26 and Ang Boon Kim, another smaller shareholder and employee of OCB, travelled to Penang and Rangoon to seek more funds to support the bank’s working capital.27

To their surprise, it was the Chinese traders in Rangoon Burma, which was then under the British rule, who were most enthusiastic about investing in a bank. They reportedly subscribed large amounts of funds thus saving the bank from liquidation. Rangoon was no strange place to Ean Kiam; he was there in 1896 with his father and he knew the potential of the place.

After returning to Singapore with the funds to capitalise the bank, he proceeded to set up branches in Penang and Rangoon to facilitate the new investors and also in recognition of the support he received from the oversea Chinese in these two cities.

Two years later in 1921, The Oversea Assurance Company Limited, the insurance arm of the bank, was formed with the same board of directors and its branches were located at the same addresses in Rangoon and Penang.

However, on 31 October 1932 the world went into deep economic depression. OCBC merged with Ho Hong Bank and the Chinese Commercial Bank to form OCBC. To recognise the efforts that Tan Ean Kiam had contributed towards the formation of the bank, he was made its first joint managing director together with Yap Twee who later retired in 1933 leaving behind Tan as the sole managing director (1934–1941).28

OCBC had its branch in Penang in 1912. The bank is located on the main street of the banking district and easily recognised by its marble facade. OCBC was in operation in Penang from the day of the merger with the Ho Hong Bank, the Oversea- Chinese Commercial Bank in 1932.29

The Patriotic Chinese

In 1916, Ean Kiam became a member of the Singapore branch of Tung Meng Hui, the nationalists’ revolutionary movement of Dr Sun Yat Sen. As a successful businessman, he was able to donate financially to support the organisation. He was also reported to be instrumental in the acquisition of the land and property for the construction of the Wan Qing Villa which later became the Tung Meng Hui Singapore base.

When Yuan Shikai30 proclaimed himself Emperor in 1916, despite universal objections especially from the Tung Meng Hui members, he donated towards the “Yuan Shikai Bei Fa” war campaign to overthrow Yuan Shikai.

The Philanthropist

Ever mindful of his role in society, Tan contributed generously to many charities. When he passed away in 1943, he left behind a large sum of money and properties from which he willed the future earnings to be used for charity.

The Tan Ean Kiam Foundation was founded in 1956 and managed by his son, (the late) Tan Tock San, located at 15 Philip Street #09-00, near Raffles Place, Singapore 048694. A row of 30 shophouses, located next to the Katong Shopping Centre, appropriately named “Ean Kiam Place”, was his bequest.

Among other donations, it was reported that 80% of the rental income generated from Ean Kiam Place funded:

- The Singapore Thong Chai Medical Institution

- Singapore Clan Association: Tong An Hui Guan

- The National Kidney Foundation

- The Lee Kuan Yew Scholarship Fund

- Tan Ean Kiam Kiam Service-Learning Resource Centre

The “Rags To Riches” Banker and The First Open University of Malaysia

Yeap Chor Ee31 (1867–1951)

Wawasan Open University, the first open university of Malaysia located in Penang, which opened its doors in 2007, was made possible because of a bequest by the late “towkay” Yeap Chor Ee.

At the age of 17, Yeap migrated from China with nothing more than the clothes he wore. Through sheer hard work, diligence and wise investment decisions over a period of about 50 years, he built his financial empire and provided for his descendents. The Wawasan Open University is a vibrant monument to Yeap Chor Ee’s benevolence in the cause of providing education for the youth of the land from where he had made his fortune.

Early Days

Yeap Chor Ee was born in Nam-An, a small village town located in Fujian Province, China. When he landed in Penang, he started his living by working as an apprentice in a shop and lived a frugal life.

By a serendipitous meeting, he got to know Goh Teik Ji, who became his benefactor. Goh Teik Ji was then a Penang-based import/ export agent of Oei Tiong Ham, the “Sugar King” of Java (Indonesia). Goh financed Yeap to start a small grocery shop of his own.

When World War I broke out, the price of sugar, which is an essential commodity, rose as a result of the disruption in the transportation services. Yeap’s shop naturally became the exclusive dealer for sugar and thus began his journey into prosperity.

Ban Hin Lee Bank (BHLB)32

From the profits of the sugar deals, he invested in some other ventures, including tin smelting and rice trading.33 In 1918, he also set up a remittance and foreign exchange business at his shop through a banking account with then Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank of Malaya in Penang. The business helped to seed the founding of BHLB, the first overseas Chinese commercial bank in Penang, Malaysia in 1935.34

BHLB indeed remained “the one and only Penang-based Chinese bank” for the next 70 years. Its landmark building, built in 1934, was designed by Ung Ban Hoe, the first Chinese architect, who was then practising with Stark & MacNeill, a British architect firm in then British Malaya.

BHLB had an original branch office building in Singapore along Upper Circular Road.35 It was strategically located near the OCBC building in Chulia Street and the United Overseas Bank building along the Bonham Street. It had other branches in Sabah and Sarawak, East Malaysia. Yeap Chor Ee’s marketing strategies at BHLB is reportedly used by May Bank and OCBC.36

The bank has since undergone several mergers and is now part of the Bumiputra Commerce Holdings Berhad, the second largest banking group in Malaysia trading under the name of the Commerce International Merchant Bankers (CIMB Bank). By the time the merger took place, BHLB group had diversified into investments and property holdings and developments. The business is now managed by Stephen Yeap Leong Huat, his grandson.

Homestead - The Former Residence and Current Administration Office at Wawasan Open University

Homestead, a grand mansion sited on a large piece of richly endowed open land, was designed by renowned British architect, James Stark of Stark & McNeil in 1919. It was originally built for Lim Mah Chye, an overseas Chinese merchant during that time. Lim Chin Guan, the son of Lim Mah Chye, reportedly controlled the Eastern Shipping Company in 1918 and according to historical records, the shipping company, which was formed in 1907, owned about 40 sailing ships.

The mansion was later acquired by BHLB and it became the home of Yeap Chor Ee and his descendants. In accordance with his will, his grandson, Datuk Stephen Yeap Leong Huat, recently handed the property over to the Ministry of Education for Wawasan Open University to commence its operations.37

The 30,000 square feet Homestead mansion, which sits on a prime 1.44 ha site, houses the campus chancellery, administration office and the new building behind houses lecture theatres.

A 2.4 metres high bronze statue of Yeap Chor Ee was placed at the front entrance of the Wawasan Open University in memory of the Chinese philanthropist whose rags-to-riches story is an inspiration to many locals.

Other Legacies

In 1924, the Yap Kongsi building, designed by Chew Eng Earn, a Straits-born Chinese architect, was built on a piece of land donated by Yeap Chor Ee. The building and the Yap Temple are dedicated to the Yap Fujian clan ancestries and their patron deities.

Jalan Yeap Chor Ee or Yeap Chor Ee Road in Penang was named after his death to remember and honour his contributions. The Yeap Chor Ee Charitable & Endowment Trust was established in1941, and in 1952 the Yeap Chor Ee Endowment Trust was set up.38

In Rangoon (Yangon), Burma, Yeap Yan Bin, the son of Yeap Swee Tong who was Yeap Chor Ee’s nephew, built the three-storey building which is located at 372 Strand Road, Rangoon Chinatown. When Swee Tong’s father died, Yeap Chor Ee became the guardian. He taught them to trade and supported them financially in business.

Swee Tong’s younger brother Yeap Swee Ah39 conducted rice exports from rice mills owned by Yeap Chor Ee. These were located in Wa-ke-ma Town, in the Irrawaddy Delta. During the period of the Japanese occupation, the Yeap siblings in Rangoon exported rice to Penang and Singapore on board Chinese junks owned by Yeap Chor Ee, who was appointed as provisions supplier for the Japanese military which had occupied Singapore.40

When Yan Bin took over Ban Lee Heng41 in Rangoon (a firm with similar sounding name to Ban Hin Lee) he started importing “two fish” brand of cooking oil and other commodities from Singapore. Although the property is still occupied by Swee Tong’s grandchildren, Yeap Chor Ee’s tablet and photographs are still placed and honoured in this property.

Conclusion

What can we learn from these Chinese personalities? Firstly, they knew no fear when they set out from their familiar home ground. They were instinctively driven from comfortable surroundings to search for new frontiers in their hunger for success or desire to seek new riches. Secondly, for those who had already achieved success or accumulated riches, their home ground became too small for their entrepreneurial ambitions. They needed new trophies to add to their treasure chest. Thirdly, there were those ousted by circumstances beyond their control. They had to find new grounds to write their success stories for future generations. Finally, there were the glimpses of riches unknown to them. There is a certain mystery as to where the characters described here would have wanted to explore by choice, but by chance they were driven from their comfort zones by circumstances beyond their control.

The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Dr Helen Reid, retired researcher in reviewing the paper.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow

National Library

REFERENCES

CHINESE BOOKS

- In Chinese

Chen Jianhong and Huang Xianqiang 陈剑虹 and 黄贤强, Binlangyu Hua ren yan jiu 槟榔屿华人研究 [Penang Chinese Studies] (Xinjia o 新加坡: Han jiang xue yuan Hua ren wen hua guan, Xinjiapo guo li da xue zhong wen xi 韩江学院华人文化馆, 新加坡国立大学中文系, 2005 ). (Call no. Chinese RCO 959.5004951 BLY)

Chen Weilong 陈维龙, Xin Ma zhu ce shang ye yin hang 新马注册商业银行 [Registered Commercial Bank in Singapore and Malaysia] (Xinjiapo 新加坡: Shi jie shu ju 世界书局, 1975). (Call no. Chinese RSING 332.12095957 CWL)

Cui Guiqiang 崔贵强, Xinjiapo Hua ren: cong kai bu dao jian guo 新加坡华人: 从开埠到建国 [The Chinese in Singapore: Past and present] (Xinjiapo 新加坡: Xinjiapo zong xiang hui guan lian he zong hui, jiao yu chu ban gong si lian he chu ban 新加坡宗乡会馆联合总会, 教育出版公司联合出版, 1994) (Call no. Chinese RSING 959.57004951 CGQ)

- In Chinese

Fang Xiongpu 方雄普, Zhu bo san ji: mian dian hua ren she hui lx’‘ue ying 朱波散记: 缅甸华人社会掠影 [The Sanji of Zhu Bo: A Snapshot of the Burmese Chinese Society] (Xiang gang 香港: Nan dao chu ban she南岛出版社, 2000). (Call no. Chinese RCO 305.89510591 FXP)

- In Chinese

Yang Baojun 杨保筠, Hua qiao Hua ren bai ke quan shu 华侨华人百科全书 [Overseas Chinese Encyclopedia] (Beijing 北京: Zhongguo Hua qiao chu ban she 中国华侨出版社, 2001). (Call no. Chinese RCO 909.04951 ENC)

-

In Chinese

-

In Chinese

Song Wangxiang 宋旺相, Xinjiapo Hua ren bai nian shi 新加坡华人百年史 [Centennial history of the Chinese in Singapore] (Xinjiapo 新加坡: Xinjiapo Zhonghua zong shang hui 新加坡中华总商会, 1993). (Call no. Chinese RCO 959.57004951 SOS)

-

In Chinese

-

In Chinese

CHINESE BOOKS ON TAN KAH KEE

-

In Chinese

-

In Chinese

All-China Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese, co-edited by Fujian Provincial Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference 中华全国归国华侨联合会, 福建省政协合编, Hui yi Chen Jiageng: ji nian Chen Jiageng xian sheng dan chen yi bai yi shi zhou nian 回忆陈嘉庚: 纪念陈嘉庚先生诞辰一百一十周年 [Memories of Tan Kah Kee: Commemorating the 110th Anniversary of Mr. Tan Kah Kee’s Birth] (Beijing 北京: Wen shi zi liao chu ban she 文史资料出版社, 1984). (Call no. Chinese RCO 959.5702092 HYC)

CPPCC Cultural and Historical Materials Research Committee 全国政协文史资料研究委员会 et al., Chen Jiageng: Chen Jiageng xian sheng dan chen yi bai yi shi zhou nian ji nian 陈嘉庚: 陈嘉庚先生诞辰一百一十周年纪念 [Tan Kah Kee : The 110th Anniversary of Mr. Tan Kah Kee’s Birth] (Beijing 北京: Wen shi zi liao chu ban she 文史资料出版社, 1984). (Call no. Chinese RSING 959.57020924 TKK.C)

Chen Bi Sheng 陈碧笙, Chen jia geng nian pu 陈嘉庚年谱 [Chronicle of Tan Kah Kee] (Fu zhou 福州: Fu jian ren min chu ban she 福建人民出版社, 1986). (Call no. Chinese RSEA 959.57020924 CBS)

Yang Jin Fa 杨进发, Chen jia geng yan jiu wen ji 陈嘉庚研究文集 [Collected papers on the studies of Chen Jia Geng] (Bei jing 北京: Zhong guo you yi chu ban gong si 中国友谊出版公司, 1988). (Call no. Chinese RCO 959.57020924 YCF)

-

In Chinese

-

In Chinese

-

In Chinese

-

In Chinese

-

In Chinese

YA YIN KWAN COLLECTION (In Chinese)

Chen Yusong 陈育崧, Ye yin guan wen cun 椰阴馆文存 [Coconut Yin Pavilion Wencun] (Xinjiapo 新加坡: Nan yang xue hui 南洋学会, 1983). (Call no. Chinese RCO 959.008 TYS)

Zeng Kenian 曾克念, Jin xiu Miandian 锦绣缅甸 [Splendid Myanmar] (Yangguang 仰光: Nan yang shu ju, Minguo 29南洋书局 民国29, [1940]). (Call no. Chinese RDTY 959.1 TKN)

Nanyang wen hua 南洋文化 [Nanyang culture] (Xinjiapo 新加坡: [Publisher not identified] [出版社缺], 1940). (Call no. RDTY 959 SCJ)

CHINESE NEWSPAPERS

-

In Chinese

-

In Chinese

-

In Chinese

-

In Chinese

-

In Chinese

SOURCES ON MICROFILM

- In Chinese

“Correspondence: Burmah,” Penang Times, 8 October 1982, 2. (Microfilm NL1990)

“Shipping Advertisement: Bibby Line,” Singapore Free Press, 13 November 1920, 8. (Microfilm NL1653)

“Shipping Advertisement: P & 0 British India Apcar Line,” Singapore Free Press, 11 June 1921, 8. (Microfilm NL1657)

“The Colony’s Affairs in 1930, Annual Review,” Singapore Free Press, 1 October 1930, 221–3. (Microfilm NL1993)

“Page 1 Advertisements Column 1: Burmah & The Straits – The Leading Hotel,” Straits Times, 2 July 1907, 1. (From NewspaperSG)

“New Ho Hong Liner,” Straits Times, 2 February 1925, 10. (From NewspaperSG)

“List of the Principal Chinese Names in Penang” in The Singapore and Malayan Directory (Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press, 1920), 313–5. (Call no. RRARE 382.09595 STR; microfilm 1190)

“Giong Ho Co. Singapore Merchants & Professions” in The Singapore and Malayan Directory (Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press, 1920), 174. (Call no. RRARE 382.09595 STR; microfilm 1190)

“The Overseas Assurance Corporation Limited” in The Singapore and Malayan Directory (Singapore: Fraser & Neave, 1924), 174. (Call no. RRARE 382.09595 STR; microfilm 1193)

Arnold Wright and H. A Cartwright, Twentieth Century Impressions of British Malaya: Its History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources (London: Lloyd’s Greater Britain Pub., 1908). (Call no. RCLOS 959.51033 TWE; microfilm NL16084)

John Crawfurd, Journal of an Embassy From the Governor-General of India to the Court of Ava, in the Year 1829 (London: Published for H. Colbrun by R. Bentley, 1834). (Call no. RRARE 959.1 CRA; microfilm NL8341)

Victor Purcell, The Chinese in Modern Malaya, 2nd ed. (Singapore: D. Moore, 1960). (Call no. RCLOS 325.25109595 PUR; microfilm NL11926)

BOOKS

Arnold Wright, Twentieth Century Impressions of Burma. Its History, People, Commerce, Industries and Resources (London: Lloyd’s Greater Britain Publishing Company, 1910)

B. R. Pearn, A History of Rangoon (UK: Farnborough, Gregg, 1971). (Call no. RCLOS q959.1 PEA)

Donald Davies, Old Singapore (Singapore: D, Moore, 1954). (Call no. RSING 959.51 DAV)

Noel F. Singer, Old Rangoon: City of the Shwedagon (Scotland: Paul Stachan - Kiscadale, 1995). (Call no. RSEA 959.1 SIN)

Sangermano, The Burmese Empire a Hundred Years Ago (Bangkok: White Orchid Press, 1995). (Call no. RSEA 959.3 CRA)

Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of Chinese in Singapore (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984). (Call no. RSING 959.57 SON)

Sarnia Hayes Hoyt, Old Penang (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991). (Call no. RSING 959.511)

Victor Purcell, South and East Asia Since1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965). (Call no. RSEA 950.4 PUR)

PAPERS

A.J.H. Latham, “From Competition to Constraint: The International Rice Trade in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries,” Business and Economic History 17 (1988): 91–102. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Chen Yi-Sein, “The Chinese in Rangoon during the 18th and 19th Centuries,” Artibus Asiae. Supplementum 23 (1966): 107–11. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

W. Daw, “Coastal Trade Between Yangon, Penang and Singapore” in Chinese Diaspora Since Admiral Zheng He: With Special Reference to Maritime Asia, ed. Leo Suryadinata (Singapore: Chinese Heritage Centre and HuayiNet, 2007), 125–35. (Call no. RSING 959.004951 CHI)

Wong Yee-Tuan, “The Big Five Hokkien Families in Penang, 1830s–1890s,” Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies 1 (2007): 106–15, https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/17848.

NOTES

-

“Rangoon” is the former name for “Yangon” during the British Rule until1989 when “Burma” officially became known as “Myanmar”. ↩

-

John Falconer et al., Burmese Design & Architecture (Singapore: Periplus, 2000) (Call no. RART 709.591 BUR): See also B. R. Pearn, A History of Rangoon (UK: Farnborough, Gregg, 1971). (Call no. RCLOS q959.1 PEA) ↩

-

During that time there were also other shipping lines, such as Straits Steamship (founded 1890) controlled from Singapore; British India Steamship Navigation Company (founded 1856) controlled from Brisbane, Australia and the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company (founded 1865) controlled from Rangoon. ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

Burmah Oil Company was acquired by Castrol and later merged into British Petroleum. ↩

-

Lim Chin Tsong had a very unique telegraphic address: “Chippychop”. ↩

-

“Singapore Merchants & Professions & Co.” in The Singapore and Malayan Directory (Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press, 1920), 310. (Call no. RRARE 382.09595 STR; microfilm 1190) ↩

-

“Singapore Merchants & Professions & Co.,” 106, 98. (microfilms NL 1192, NL1993) ↩

-

“Singapore Merchants & Professions & Co.,” 174. (microfilm NL1190) ↩

-

A two-volume history of Burmah Oil Company written by T.A.B. Corley, A History of the Burmah Oil Company, 2 vols. (London: Heinemann, 1983–1988). (Call no. RSEA 338.762233820941 COR). The Burmah Oil Company was founded in Glasgow, Scotland in 1896 by David Sime Cargill. ↩

-

Cherry Lewis, The Dating Game (UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000) ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

A mission in 1940 led by Tan Kah Kee to represent the Singapore and Southseas China Relief Funds for comforting the wounded and for assessing the war conditions in China. ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

“One of the Directors of the Oversea-Chinese Bank Limited,” Berita OCBC 3, no. 5 (October 1972): 4. (Call no. RSING 332.12095957 BOCBC) ↩

-

Sin Kuo Min Jit Poh, 8 October 1919. ↩

-

“One of the Directors of the Oversea-Chinese Bank Limited,” 6. ↩

-

Berita OCBC 15, no. 6 (August 1984): 8. (Call no. RSING 332.12095957 BOCBC) ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

Ban Hin Lee Trading was appointed by the Japanese as rice stockist during Japanese Occupation. Yap Siong Yu, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 27 June 1983, MP3 audio, 27:44, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000286) ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

A Upper Circular Road, Singapore, Yeap Chor Ee was also a director of OCBC (1933–1941), Berita OCBC 3, no. 5 (October 1972): 3. (Call no. RSING 332.12095957 BOCBC) ↩

-

David Chew Beng Hwee, oral history interview by Lim Boon Seong, 20 December 1990–20 August 1991, MP3 audio, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001234) ↩

-

Stephen Yeap Leong Huat, “Wawasan Open University Ground Breaking Ceremony,” speech, 8 January 2006, https://www.wou.edu.my/wou-college-main-campus-ground-breaking-ceremony/. ↩

-

Yeap, “Ground Breaking Ceremony.” ↩

-

The descendents of Yeap Swee Ah are now living in 20’ Street, Yangon Chinatown, Myanmar. ↩

-

In Chinese ↩