Building the Mosaic: In Search of Southeast Asian Contemporary Art Writing and Publications

Senior Librarian Roberta Balagopal considers the dearth of critical published information on Southeast Asian contemporary visual art and artists and how to fill that gap.

Southeast Asian contemporary visual art, despite its vibrancy and visibility, suffers from a dearth of useful published information with which to interpret it. It is a challenge to find art criticism, biographies and histories of reasonable depth on the subject, requiring lengthy and skilled research.

Few would dispute the importance of gathering and preserving information on contemporary Southeast Asian artists. This is what forms the core of art scholarship – having a body of literature to draw upon and discuss. Currently, the information on Southeast Asian art is scattered, of varying authority and degrees of accessibility (both physical and linguistic). This is the difficulty, to some extent, of all contemporary art. The information being produced is great in volume and often of an ephemeral nature, and the only way for art critics and art historians writing in their separate echelons to have a meaningful exchange and move forward together is for everyone to read everything, or at least to read something from every genre (Elkins, 2003). For Southeast Asian contemporary art, the challenge is exacerbated by the lack of regularly published journals that focus on the region, and a simple lack of art historians and knowledgeable critics. The scattered bits that do get recorded are collected with varying regularity by museums, curators, academics and other bodies such as archives and libraries.

Who Is Publishing It?

Scholarly art publishing has a limited market at best, and even the more accessible “coffee table” genre of books, if produced well, are expensive to make. Items published in conjunction with an exhibition feature prominently, and have a high degree of authoritativeness by virtue of their panels of guest expert writers. Museum exhibits, however, have a national agenda, and the subject matter of these books, as they accumulate over the years, will reflect that. Private and school galleries also produce such catalogue-books, but the distribution is limited to their audiences and seldom reaches beyond.

Who Is Reading It?

Without a clear knowledge of who is interested in reading such works, writers, publishers and collectors are working blind. Researchers will read on a needs-basis, as will curators, and probably a portion of art critics. Whether other artists read history and criticism regularly is less clear, though some certainly do. Two other groups of readers remain on the sidelines: student artists and interested laypersons. Student artists are apprentice artists in the process of acquiring skills and observing role models. The interested layperson is someone who knows something either of the region or of art in general. He or she may also have had some exposure to modern/postmodern art elsewhere in the world, but would be interested to obtain some regional context in terms of styles, movements and cross-border influences. These are the cross-disciplinary readers, or the informed non-specialists. It is via the readership of the above groups that interest in art is vitalised, publicised and brought to the attention of those with the economic power to sustain it.

The Art Book

The art book is, in essence, a democratising tool. Due to its reproducibility, it brings art within reach of those who may never be able to own (or possibly even see in person) the original artwork. However, art book publishing does not come cheap. Publishers estimate that an art history book produced today costs three times as much as other genres of scholarly books (Soussloff, 2006). It raises the question whether publishers who focus on Southeast Asian topics have the resources to produce quality art books, and if the market is large enough to recoup their investments. Very few publishers exist who can claim Southeast Asian art as a niche area, and the list thins even further if we were to only consider contemporary art of the region.

In Southeast Asia (as well as in Southeast Asian studies departments in Europe and North America), scholarly publishing on art has generally been sparse. Often it emerges in a thesis or in a collection of papers published by academic presses, and is frequently a type of ethnographic study, which treats art as an anthropological experience. The result may be a specialised report, integral to augmenting the research of a very narrow field, but presupposes a certain degree of advanced knowledge on the part of the reader.

The non-academic publication seems to emerge at its best when partnered with galleries and museums. Exhibition collaterals can range from low cost brochures to luxuriously produced books combining quality scholarship and visuals. The content can be both a good marketing tool for the museum and a valuable resource for researchers, if done by knowledgeable curators and authoritative guest writers. When done well, such publications provide the next best thing to a guided tour, and they document and discuss the artworks in terms that are comprehensible to the layperson. However, the disadvantage of museum publications is the ever-present danger that “politics and curatorial egos” may override other considerations that are crucial to making readable and informative books (Lyon, 2006).

Apart from the museum exhibition book, most other nonscholarly forms of monographs are targeted directly at the tourist market, in the form of inexpensive guidebooks and coffee-table books, which function similarly to tourist brochures and sales catalogues.

While works that provide comprehensive overviews of the region’s art scene are few and far between, there are books that focus on a particular period of time in a particular country, or on a single artist. Such micro-approaches contribute to building the larger mosaic of Southeast Asian contemporary art.

Books on Individual Artists

These are beginning to emerge, as with the passing of first-generation pioneer modern artists of the 1930s–1950s, there are compelling reasons to document their lives and works. While not primarily biographies, artist retrospectives also appear at intervals, often sponsored by galleries and museums to accompany a show of recently donated materials. This type of publication is especially common for painters from Indonesia and the Philippines, and is gradually expanding to Thailand, Vietnam, Singapore and elsewhere in the region. Examples of such retrospectives include: Edades: National Artist (1979), Hendra Gunawan: A Great Modern Indonesian Painter (2001) and Convergences: Chen Wen Hsi Centennial Exhibition (2006).

Thematic Books

These books focus on recurring themes or subjects in a country’s art, often incorporated into a survey of the country’s “modern era”. Themes can encompass social or spiritual concerns, or notions of aesthetics and style. It can also serve as an expression of a country’s cultural history as told through art. Such thematic books rarely make comparative studies of issues across nations, although parallels with other Southeast Asian countries do exist and are sometimes briefly acknowledged. Some examples of thematic works include: Modern Art in Thailand: Nineteenth And Twentieth Centuries (1992), Soul, Spirit, and Mountain: Preoccupations of Contemporary Indonesian Painters (1994) and Protest/Revolutionary Art In Philippines, 1970–1990 (2001).

Biographical Dictionaries

Biographical dictionaries focus on artists of a particular country or region. They contain a brief biography, often a resume of sorts, as well as a quote or short interview, and some samples of the artist’s works. The emphasis here is primarily on documenting the biographical details of the individual artists, and the authors/contributors seldom draw parallels between the artists or works: Southeast Asian Art Today (1996), Masterpieces Of Contemporary Indonesian Painters (1997), Singapore Artists Speak (1998) and Faith + The City: A Survey of Contemporary Filipino Art (2000).

A “Story” of Southeast Asian Contemporary Art?

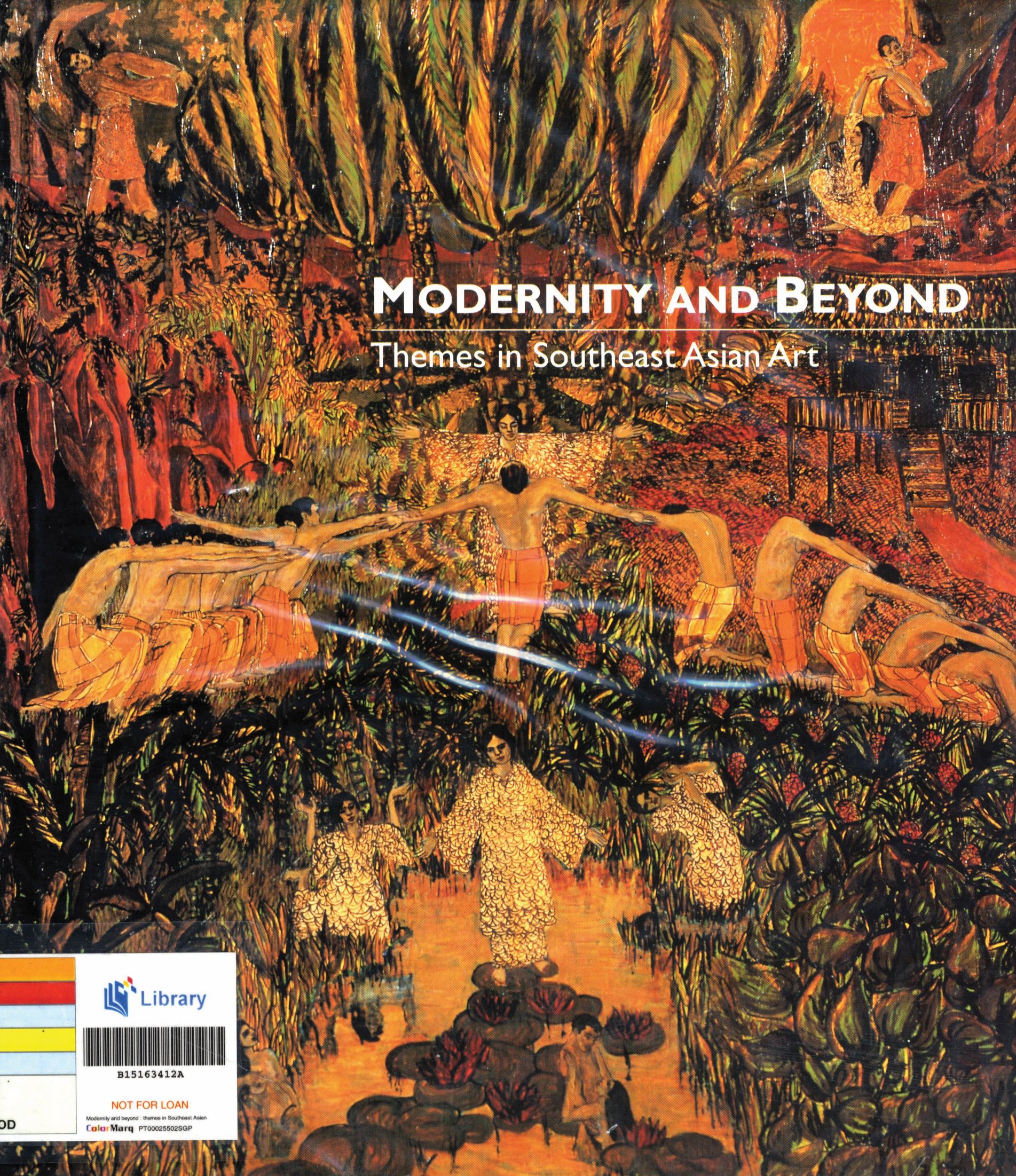

As with thematic books, the chapters in these publications are still devoted to a single country, but certain transnational themes may emerge. However, given that there are usually different authors for each chapter, a lack of a unified voice may result. Even so, a few books do come close to providing an overview of Southeast Asian modern/contemporary art: Modernity and Beyond: Themes in Southeast Asian Art (1996), South East Asian Art: A New Spirit (1997), Visual Arts in ASEAN: Continuity and Change (2001), Art and Social Change: Contemporary Art in Asia and the Pacific (2004) and Art and AsiaPacific Almanac (2006).

Art Journals and Newspapers

Some of the best barometers of the contemporary art world are journals, a number of which have existed for decades or longer, while others appear for as few as one issue and then disappear.

The art journal has much more flexibility than the art book. It does not incur the same investment risks as printing a book, it can position itself at any point in a continuum between art-as-entertainment and serious art scholarship, and it can employ writers with a variety of credentials. Asian art is permeating the contemporary art world in North America and Europe, a fact that is apparent in journals like Art and AsiaPacific Quarterly, which is a valiant effort to chart the highlights of the rapidly changing Asian art scene and situate it in the international art world. Another example is AsianArtNews, which is a similar tour of Asian art happenings and personalities. Both publications are filled with gallery advertisements, and the critical content, though present, is sometimes hard to spot. In terms of writing style, these publications are more akin to newspaper arts coverage than to scholarly journals.

The local newspaper is another source that can be relied upon to have some mention of regional contemporary artists, if they are actively showing their works. There are a couple of challenges to such sources of information, however. Firstly, they may require a competent reading knowledge of languages other than English. Secondly, news reports are intended to be brief and, regardless of the knowledge and authority of the author, can at best have time for only a cursory treatment of the topic. There are a few exceptions in newspapers with regular arts columns and dedicated critics, but even in large markets like the United States, newspaper coverage of art is declining (Plagens, 2007). More significantly, there are difficulties in finding a suitable voice and a stable readership for such works. Columnists seem to be not entirely sure who is reading it and why, and it is not clear whether the situation calls for a critical voice, a marketing pitch, or a neutral description. While a worthwhile and often necessary resource, newspaper art coverage remains difficult to use for research purposes.

Art on the Web

“Print publications have dwindled across the region over the last couple of years, magazines such as Singapore’s Focas and Vehicle; transit and Art Manila Quarterly in the Philippines, and Malaysia’s art corridor and TanpaTajuk. Increasingly, they have been replaced by artist websites, blogs and on-line publishing. One wonders what will become of the permanency of the printed voice as it is replaced by virtual dialogue?” (Fairley, 2006)

Freely available information on the Internet has two main drawbacks: it is chronically disorganised, and rigorous accuracy is not guaranteed. Nevertheless, it is often the only – and sometimes even the best – tool to find information on Southeast Asian contemporary artists.

Websites with good track records for authoritative information on art and artists are ones with reputations to build and protect, such as national galleries and art museums. These aim to attract discerning visitors, including scholars and writers, and accuracy is important. For the researcher who is unable to visit regularly in person, websites with catalogues of works online are invaluable. Examples of digital collections include the Balai Seni Lukis Negara (National Art Gallery Malaysia) and Ateneo Art Gallery in the Philippines. Other organisations such as the Asia Art Archive (https://www.aaa.org.hk) create online projects like their current feature on international biennials.

Other useful web resources, which may be called “e-magazines”, have emerged and remain active. For example, The Substation magazine (https://www.substation.org/), though updated sporadically, is one of the very few currently active sources for in-depth investigation of contemporary art in Singapore. Another example is Kakiseni (kakiseni.com), a portal of all manner of contemporary arts-related news and concerns in Malaysia, which also includes a searchable archive of about 800 articles and interviews with artists.

Artists themselves may have created their own websites, and these, at their best, can serve a purpose similar to personal journals or scrapbooks. Artists may also use the web as a simple shop front to promote and sell artworks, which is potentially useful for the collector but less so for the researcher. Online shop fronts of galleries sometimes yield important information, for example, the Thavibu Gallery website (https://www.thavibu.com) provides links to articles on Thai, Vietnamese and Burmese art, including ones from reputable print publications. The underlying purpose, of course, is to promote certain artworks and artists.

The internet also provides a platform for the amateur historian and critic via blogs, wikis and informal information collectives. These sources are the most difficult to assess in terms of authority and informativeness. It requires the researcher to know the subject well already, and be able to sift through possibly irrelevant or erroneous information to find useful areas to investigate further. It also requires the researcher to be familiar with local languages, dialects and cultural references.

This type of web community effort is useful for information leads, but unfortunately for the researcher, its anonymous nature makes the cross-checking of information much more difficult.

Despite its shortcomings, it is undeniable that web-based information is shifting the balance of power from printed to digital sources.

The Future of Southeast Asian Art Writing and Publishing

How Can Art Writing and Scholarship Be Sustained?

Two areas have some power to help sustain critical thinking and investigation about Southeast Asian contemporary art. Firstly, writers and publishers can cultivate audiences, sharing beyond disciplinary boundaries to reach a wider readership. The difficulty of the current state of things seems to lie with the exceptions of museum and gallery-generated materials and a handful of non-specialist books and journals, in the insubstantiality or inaccessibility of art criticism to the non-specialist reader and student.

For Southeast Asian contemporary art, a critical mass of information in a fairly accessible form has yet to be built. The history of Southeast Asian contemporary art in context needs to be read, criticised, studied, written and rewritten by a wider audience. The notion of contemporary art in Southeast Asia as elitist is not without basis when discussion of any depth is held aloof from all but scholars. Admittedly, an overview of Southeast Asian contemporary art in the Western art history style poses a host of difficulties, not the least of which is that, in a non-European context, the notion of art having a “history” is itself questionable (Elkins, 2002). However, there is an air of inevitability to this approach. As the birth of modern art in Southeast Asia starts to be researched and written about, it begins to take its place as a historical period and, rightly or not, a chapter in the story of Southeast Asian art. While this over-simplifies and imposes a linear element, contemporary art itself needs a past reference (if only to parody or deconstruct it) in order be innovative, and innovation seems to be an obsession with contemporary artists worldwide (Timms, 2004). Innovation also ensures that art writers and researchers take notice and record their interpretations. In short, without a documented and dissected past, contemporary art loses something of its purpose and identity.

Secondly, all organisations producing art writing can make a concerted effort to consolidate these writings in a durable format, and deposit copies with libraries or archives. Worldwide, art libraries face similar challenges in documenting contemporary art. In 2005, the Asia Art Archive organised an international workshop entitled “Archiving the Contemporary”, the results of which parallel concerns of art library associations in North America, the United Kingdom and elsewhere. Multifarious formats make it challenging to build collections, though at the same time they also make the collection richer and more balanced, when taken in its entirety. Despite the difficulties, libraries and archives can and do take on the uphill task of preserving these art forms, and make room for them within limited budgets.

Together, these two strategies focus on improving access to information, by improving the quality of the materials themselves and by making them easily available to readers. As Southeast Asian contemporary art writing and publishing evolves over time, access to this information will remain the key to its continued survival.

Senior Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library

REFERENCES

“A Foot in the Malaysian Arts Scene!” Kakiseni (2001–), http://www.kakiseni.com/.

Abdul Ghani Haji Bujang et al., Visual Arts in ASEAN: Continuity and Change (Kuala Lumpur: ASEAN Committee on Culture and Information, 2001). (Call no. RSING 709.59 VIS)

Agus Dermawan T. and Astri Wright, Hendra Gunawan: A Great Modern Indonesian Painter (Singapore: Archipelago Press, 2001). (Call no. RSING q759.9598 AGU)

Alice G. Guillermo, Protest/Revolutionary Art in Philippines, 1970–1990 (Philippines: University of the Philippines Press, 2001). (Call no. RSEA 700.9599 GUI)

Apinan Poshyananda, Modern Art in Thailand: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1992). (Call no. RSEA 709.593 API)

Art and AsiaPacific Almanac (New York: Art AsiaPacific Pub., 2006). (Call no. RART 709.5 AAPA)

Art and AsiaPacific Quarterly Journal (1993–). (Call no. RART 709.5 AAQJ)

Asia Art Archive, (n.d.), accessed 16 March 2007, http://www.aaa.org.hk/.

AsianArtNews (1991–2020). (Call no. RART 709.505 AAN)

Astri Wright, Soul, Spirit, and Mountain: Preoccupations of Contemporary Indonesian Painters (Malaysia: Penerbit Fajar Bakti, 1994). (Call no. RSEA 759.95980904 WRI)

Ateneo Art Gallery, n.d. accessed 16 March 2007, https://ateneoartgallery.com/.

Balai Seni Lukis Negara [National Gallery of Art], n.d., accessed 16 March 2007, http://www.artgallery. gov.my/.

Caroline Turner, ed., Art and Social Change: Contemporary Art in Asia and the Pacific (Canberra: Pandanus Books, 2004). (Call no. RART 701.03095 ART)

Catherine M. Soussloff, “Publishing Paradigms in Art History,” Art Journal 65, no. 4 (Winter 2006), 37–38. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Chen Wenxi, Convergences: Chen Wen Hsi Centennial Exhibition (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2006). (Call no. RSING 759.95957 CHE)

Christopher Lyon, “Art Book’s Last Stand?” Art in America 94, no. 8 (September 2006), 49–50. (Call no. RART 705 AA)

Emmanuel Torres, Ana Labrador and Jessica Zafra, Faith + the City: A Survey of Contemporary Filipino Art (Kuala Lumpur: Valentine Willie Fine Art, 2000). (Call no. RSEA 759.9599 TOR)

Esmeralda Bollansee and Marc Bollansee, Masterpieces of Contemporary Indonesian Painting (Singapore: Times Editions, 1997). (Call no. RART 759.9598 BOL)

Gina Fairley, “Art Without Prejudice,” sentAp! no. 3 (April–June 2006), https://universes.art/en/nafas/articles/2006/sentap.

James Elkins, Stories of Art (London: Routledge, 2002). (Call no. RART 707.22 ELK)

James Elkins, What Happened to Art Criticism? (Chicago, Ill.: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003). (Call no. RART 701.18 ELK)

Joyce van Fenema et al., Southeast Asian Art Today (Singapore: G and B Arts International, 1996). (Call no. RART 709.5909045 SOU)

P. Plagens, “Contemporary Art, Uncovered,” Art in America 95, no. 2 (2007), 45. (Call no. RART 705 AA)

Peter Timms, What’s Wrong With Contemporary Art? (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2004). (Call no. RART 709.05 TIM)

Purita Kalaw-Ledesma and Amadis Ma. Guerrero, Edades: National Artist (Manila: Filipinas Foundation, 1979). (Call no. RSEA 759.9599 EDA)

Richard Lim, ed., Singapore Artists Speak (Singapore: Raffles Editions, 1998). (Call no. RART 709.5957 SIN)

Singapore Art Museum, Modernity and Beyond: Themes in Southeast Asia Art (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 1996). (Call no. RART 709.59 MOD)

South East Asian Art: A New Spirit (Singapore: Art & Artist Speak, 1997). (Call no. RART 709.59 SOU)

Thavibu Gallery: Contemporary Art from Thailand, Vietnam and Burma (1998–), accessed 16 March 2007, https://www.thavibu.com/index.php.

The Substation Magazine (2007), accessed 16 March 2007, http://www.substation.org/mag/.