Social Innovation in Singapore: Two Case Studies of Nongovernmental Organisations

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow Zhang Liyan examines the phenomenon and role of social innovation in Singapore’s historical and post-independence development through Chinese clan associations and grassroots organisations.

Abstract

Nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) have long been a force for social innovation in Singapore society. Along with the government and the private sector, they have been an important part of the “Singapore model” that has built a prosperous, just and caring society with a high quality of life that is the envy of the world. This paper concentrates on two types of NGOs: Chinese clan associations and grassroots organisations (GROs), both of which are extremely important from the specific standpoint of social innovation in Singapore. The influence of Chinese clan associations was at its peak in the colonial period when Singapore was an underdeveloped society with an immigrant Chinese majority. GROs became important during the post-independence period of nation-building, in tandem with rapid economic development.

Introduction

In this paper, I examine the phenomenon and role of social innovation in Singapore’s historical and post-independence development by analysing two types of NGOs – Chinese clan associations and GROs. I chose to focus on these two types of NGOs for two reasons. First, the Chinese clan associations were the NGOs that affected the most people in Singapore during most of the colonial period, since the Chinese constituted the majority of the population then. Second, GROs deserve special attention because they are the first community-based NGOs which represented the entire population of Singapore, and also because they have provided a unique platform for cooperation and feedback on social and economic development between the people and the People’s Action Party (PAP) government. Using these two case studies, I will examine the role NGOs played in the social innovation of Singapore.

Case Study 1: Chinese Clan Associations

The Emergence of Chinese Clan Associations

The modern history of Singapore began in 1819 when Stamford Raffles established a British port on the island. From 1824 to 1872, Singapore’s trade greatly increased as it grew from a trading post to an important port city, attracting many people from China to migrate to Singapore. “In the 1840s, after China lost the Opium War, there was an exodus of Chinese migrants to all parts of South-east Asia.”1 The 1911 Revolution failed to solve China’s political, social and economic problems, and wars subsequently broke out between the different warlords. The unstable social situation forced many Chinese to leave their homeland to seek a better life elsewhere.

Most of the early Chinese migrants arrived in Singapore virtually penniless and faced problems such as finding employment, lodging and friends. Hence the birth of Chinese clan associations, which offered humanitarian assistance to the early immigrants. These associations helped new immigrants to settle down and seek employment. The other main preoccupations of the associations were sponsoring education and helping destitute members (Wickberg, 1994).

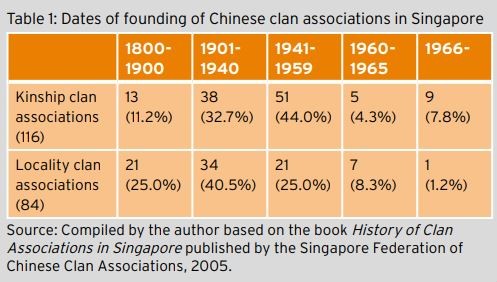

In 2005, the Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations published a book entitled History of Clan Associations in Singapore.2 This book documented 200 Chinese clan associations, comprising 116 kinship clan associations and 84 locality clan associations. More than 90% of these clan associations were set up before 1960. Table 1 provides information on the founding of some Chinese clan associations.

The development of Chinese clan associations was at least partly a result of colonial policy. Within the colonial structure, the British administration left the various ethnic communities alone to handle their own social, culture, economic and political affairs, seldom intervening at all. The non-interventionist policy of the British colonial government thus led to the necessity for and development of Chinese clan associations.

Before Singapore became self-governing in 1959, Chinese clan associations concentrated on humanitarian assistance, the religious needs and welfare of their members. The associations helped new immigrants find jobs and establish useful contacts, provided shelter and food, and ultimately a sense of belonging to a community.

The clan associations also provided help to those in financial need. Early migrants had no social security, so clan associations provided welfare services to look after the sick, destitute and widows. The clan associations organised communal social and religious activities that offered much-needed interaction and breaks in the otherwise mundane and routine life of the coolies. One of the most important functions that clan associations served at the time was the offering of funeral services. Clan associations also acted as intermediaries in intracommunity conflicts: “The familiarity of cultural practices reproduced in the alien colonial environment helped many to cope with the monotonous working life, loneliness and homesickness that came with their isolated migrant lifestyle” (Khun Eng Kuah-Pearce, 2006, p. 54).

As the Chinese immigrant population grew, education, cultural and other social needs also had to be met. From the late 19th century onwards, these clan associations not only helped newly arrived people in their community to settle down, but also financed schools and scholarships for the children of migrant families.

The Decline of Chinese Clan Associations

At the Lee Clan General Association’s 86th Anniversary Dinner on 28 October 1992, Brigadier-General Lee Hsien Loong said: “Since independence in 1965, many of the services the clan used to provide have been taken over by the Government and other civic organisations… the government took over the running of schools and public services. Thus the Chinese clan started to lose its appeal and purpose towards the community and thus they experienced a dwindling membership.”3 Furthermore, English was being taught as the first language in schools. This weakened the link between the clan associations and the younger generations. By the end of the 1970s, Singapore’s housing and urban renewal programme had resettled people in new public housing estates, and this further eroded the connectedness of the Chinese community. This was a major factor that led to the decline of Chinese clan associations, some of which became inactive or dormant.

The Revival of Chinese Clan Associations

Since the late 1970s, Chinese clan associations faced many obstacles in sustaining their existence. The associations tried to keep up with the changing practical and psychological needs of their members while adjusting to the growth of the nation-state and the changing sociopolitical environment. “Interestingly, the government suggested that clansmen organisations should take up a role in reinforcing Chinese values, ‘Asian values’ and Asian identity. Clansmen associations are viewed as the roots of Chinese culture and tradition, which in the government’s view should be cultivated and preserved” (Chan, 2003, p. 79). Clan associations therefore were a good medium through which the nation could revive Chinese traditions and reinforce the Chinese identity.

In 1978, China started implementing economic reforms which resulted in rapid economic development, which in turn attracted the attention of the world. The revival of Chinese culture and traditions in Singapore became important at that juncture. The Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations (SFCCA) was formed in 1986, and marked a major turning point in the history of the clan associations.

In recent years, numerous clansmen fellowship meetings have taken place one after another in various countries around the world. The conventions have moved from their original emphases on clan ties and ancestral roots to cultural, economic, trade and academic exchanges. Cooperation between clan associations in Singapore and other overseas Chinese voluntary associations has also revitalised links with China, and networks have been reconstructed for investment and economic purposes (Liu, 1998).4

The changing social functions of Chinese clan associations reflect the corresponding changes in Singapore society, which was experiencing a new awareness of a Chinese cultural identity. This evolution more importantly demonstrates the resilience of cultural systems and their ability to respond to the changing needs of their members and the state.

Case Study 2: Grassroots Organisations

The Emergence of Grassroots Organisations

GROs are uniquely Singaporean forms of NGOs that are guided and supported by the government and hence represent social innovation as a vehicle for government-people cooperation and feedback. When self-government was attained in 1959, the Singapore government had to overcome serious political, economic and communal problems to survive.

The People’s Association (PA) was formed on 1 July 1960. In the words of its mission statement: “The People’s Association brings people together to take ownership of and contribute to community well-being. We connect the people and the government for consultation and feedback. We leverage these relationships to strengthen racial harmony and social cohesion, to ensure a united and resilient Singapore.”5 To rally grassroots support and to promote better rapport between the government and its people, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew began a two-year tour of all the constituencies in Singapore in 1962. During this tour, Lee discovered the importance of support at the grassroots level and came across outstanding grassroots leaders, who were later chosen to head grassroots organisations. After the PAP won the election in 1963, Lee decided to institutionalise the grassroots organisations in Singapore. Grassroots organisations are community-based volunteer organisations with strong government support through the PA. They are thus a unique social innovation that connects people with the government through non-government initiatives, and facilitates social and economic development through cooperation and public feedback.

Before the PA was established in 1960, there were 28 community centres (CCs) “providing a place for local residents to participate in social and recreational programmes and more specifically to disseminate colonial government policies and information. The first two of these were opened in 1953 in Serangoon and Siglap constituencies” (Vasoo, Tang & Ng, 1983, pp. 1–2). The PA took over these community centres. Unfortunately, the facilities of the centres then were few and far between (吴俊刚 and 李小林, 2000, pp. 39–44). Therefore, the first programme implemented by the PA after its inauguration was to set up a large network of community centres throughout the island. Each constituency had several community centres. “Besides debunking communist bogeys and providing government information these community centre also organised social, cultural and recreational programmes for the young and old living in various neighborhoods” (Vasoo, Tang & Ng, 1983, p. 2). Until the early 1970s, the members of the community were not enthusiastic about the activities at the community centres, as facilities were not adequate. From the mid-1970s, community centres were built with modern decor and state-of-the-art facilities. The community centres were called Community Clubs since 1990.

The Community Centre Management Committee (CCMC) was formed in 1964. CCMC was the first pure community-based volunteers’ organisation in the system of grassroots organisations in Singapore.6 The members and leaders of the CCMC needed, however, to be approved by the PA. Each CC had a CCMC to plan and organise the centre’s activities following the rules of the PA.

The Citizens’ Consultative Committees (CCCs) was formed in 1965 when Singapore gained independence. Each constituency had one CCC as the apex grassroots organisation in that constituency. At the time, the infrastructure was not well developed. The CCC connected the government with its residents and offered suggestions for improving Singapore’s infrastructure. CCC also played an important role in promoting racial harmony and helping the poor.7 For more than 40 years now, they have played an integral part in Singapore’s social cohesion. CCCs were extremely important in the 1960s and 1970s when Singapore underwent its resettlement movement. During the resettlement process, Singaporeans had to get used to living in a new environment in close proximity to other racial groups. Some were not satisfied with the government’s compensation package. The relationship between the government and these uprooted people then was very tense. The CCCs mediated by explaining the government’s policies to the people and provided feedback to the government and the tensions were eventually eased.

In 1978, the first Residents’ Committee (RC) was formed as a result of Singapore’s housing and renewal programme to promote neighbourliness and harmony in public housing estates. The importance of CCCs declined after this. Each RC had an RC Centre to conduct meetings, programmes and activities for residents. In the private housing estates, Neighbourhood Committees (NCs) encouraged active citizenry and fostered community bonds.8 As with the CCMC, CCCs, RCs and NCs were community-based volunteer organisations.9 Members and leaders of these NGOs had to be approved by the PA.

Within the GRO system, the CCCs were at the pinnacle of each constituency and were responsible for planning and leading grassroots’ activities to promote good citizenship among its residents. The CCCs presided over community and welfare programmes, channelled feedback between the government and its people, disseminated information, and made recommendations on the development of public amenities and facilities.

The functions of the RCs and NCs were: to promote neighbourliness, harmony and cohesiveness among the residents, to liaise with and make recommendations to governmental authorities on the needs of residents; to disseminate information and channel feedback on government policies and actions from residents; and to promote good citizenry.10 The RCs and NCs organised residents’ parties, conducted house visits and other neighbourhood activities to reach out to residents. Run by residents for residents, the RCs/NCs also worked closely with other grassroots organisations and government agencies to improve the physical environment and safety of each local precinct.

The GROs were structured hierarchically. At the constituency level, there was a CCC comprising volunteers. Under each CCC, there were several CCs composed of volunteers and PA staff. In addition to the activities mentioned above, CC staff members attended the RCs/NCs meetings. CC staff periodically reported to the CCCs, which provided feedback and guidance. Despite the hierarchy, the channels of communication between the government and citizens were multilevel. Citizens could approach CCs, RCs, NCs or members of Parliament (MPs) at the Meet-the-People Sessions (MPS) whenever they had problems they wanted resolved.11

Since independence, the Singapore government believed that community issues needed to be managed by the community members themselves, and transferred some of the powers of the government agencies to the grassroots organisations, which formed the bases of the GROs’ system. GROs became a pillar of the PAP government and part of PAP’s political strategy. Over the years, many national movements, such as the National Courtesy Campaign and National Clean-up Campaign, were successfully implemented with the help of GROs. GROs drew on the traditional attitudes of community leaders and the assistance of community volunteers to form a network of organisations, and offered accessible venues and facilities for interaction and community services.

Institutionalisation of Grassroots Organisations

Most of the challenges facing the communities required locally driven and creative solutions rather than a heavy-handed top-down approach of traditional government bureaucracies and programmes. GROs were community-based NGOs that were closely linked to the government. The GRO volunteers were residents who were energetic, passionate and proposed activities, initiatives, services and processes to address the social and economic challenges faced by their communities.

Through the nation-wide GROs network, the social services delivered by the Singapore government addressed Singaporeans’ needs comprehensively.

The two types of NGOs discussed in this paper successfully carried out their goals and functions under contrasting conditions of a relatively non-interventionist state during the colonial period, and a highly interventionist state and weak civil society in the post-independence period respectively. The Chinese clan associations adapted to changing economic and social conditions by shifting their emphasis to cultural preservation. GROs, despite a weak civil society and a strong state, made themselves indispensable to the state as much as they were ultimately dependent on state regulation. Both types of NGOs have over the years demonstrated their robustness and adaptability to varying economic and sociopolitical conditions, and have played no small part in helping Singapore evolve into the thriving city-state it is today.

The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Dr Sai Siew Min, Assistant Professor, Department of History, National University of Singapore in reviewing the paper.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow

National Library

REFERENCES

Edgar Wickberg, “Overseas Chinese Adaptive Organizations, Past and Present,” in Reluctant Exiles: Migration From Hong Kong and the New Overseas Chinese, ed. Ronald Skeldon (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1994), 68–86.

Hong Liu, “Old Linkages, New Networks: The Globalization of Overseas Chinese Voluntary Associations and Its Implications,” China Quarterly no. 155 (September 1998), 582–609. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

K.E. Kuah-Pearce, “The Cultural Politics of Clan Associations in Contemporary Singapore,” in Voluntary Organizations in the Chinese Diaspora, ed. Khun Eng Kuah-Pearce and Evelyn Hu-Dehart (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2006), 53–76. (Call no. RSING 366.0089951 VOL)

Kersty Hobson, “Considering “Green” Practices: NGOs and Singapore’s Emergent Environmental-Political Landscape,” Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 20, no. 2 (October 2005), 155–76. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Mark Goldenberg, “Social Innovation in Canada: How the Non-Profit Sector Serves Canadians … and How It Can Serve Them Better,” (Research Report, CPRN Discussion Paper, November 2004)

Maurice Freedman, Chinese Family and Marriage in Singapore (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1957). (Call no. RSING 301.42 FRE)

Nancy Macduff, “Engaging Ad Hoc Volunteers: A Guide for Non-profit Organizations,” adapted from Episodic Volunteering: Organizing and Managing the Short-Term Volunteer Program (Singapore: National Volunteer & Philanthropy Centre, 2004)

Oral History Department, Singapore 口述历史馆, Xinjiapo huaren huiguan yange shi 新加坡华人会馆沿革史 History of Singapore Chinese Associations (Xinjiapo 新加坡: Xinjiapo xin wen yu chu ban gong si 新加坡新闻与出版公司, 1986). (Call no. RSING Chinese 369.25957 HIS)

S. Vasoo, Winnie Tang and Ng Guat Tin, A Manual on Community Work in Singapore, 2nd ed. (Singapore: Singapore Council of Social Service, 1983). (Call no. RSING 361.95957 MAN)

Salamon, Lester M. and Helmut K. Anheier. “The International Classification of Nonprofit Organizations: ICNPO-Revision 1, 1996.” (Working Papers of the Johns Hopkins Comparative Non-profit Sector Project, no. 19, 1996)

Selena Ching Chan, “Interpreting Chinese Tradition: A Clansmen Organization in Singapore,” New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 5, no. 1 (June 2003), 72–90.

Wu Jungang and Li Xiaolin 吴俊刚 and 李小林, Li guang yao yu ji ceng zu zhi 李光耀与基层组织 [Lee Kuan Yew and Grassroots Organizations] (Xin jia po 新加坡: Sheng li chu ban gong si 胜利出版公司, 2000). (Call no. Chinese RSING 307.095957 WJG)

Yayoi Tanaka, “Singapore: Subtle NGO Control by a Developmentalist Welfare State,” in The State and NGOs: Perspective From Asia, ed. Shinichi Shigetomi (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2002), 200–21. (Call no. RSING 068.5 STA)

NOTES

-

Oral History Department, Singapore 口述历史馆, Xinjiapo huaren huiguan yange shi 新加坡华人会馆沿革史 History of Singapore Chinese Associations (Xinjiapo 新加坡: Xinjiapo xin wen yu chu ban gong si 新加坡新闻与出版公司, 1986), 20. (Call no. RSING Chinese 369.25957 HIS) ↩

-

This book’s coverage of clan associations is not comprehensive, being limited to the Federation’s members. However, since the Federation included most of the active associations, the information provided in this book is relevant. According to Lim Boon Tan, Executive Director of the Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations, there are currently around 300 clan associations registered under the law. However, less than 100 of these are currently active. (I interviewed Lim Boon Tan on 2 July 2008 at the Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Association.) ↩

-

“Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan,” accessed 20 June 2008, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Teochew_Poit_ Ip_Huay_Kuan ↩

-

Hong Liu, “Old Linkages, New Networks: The Globalization of Overseas Chinese Voluntary Associations and Its Implications,” China Quarterly no. 155 (September 1998), 582–609. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Cited from the mission statement of the People’s Association, https://www.pa.gov.sg/about-us/about-pa/ ↩

-

According to Tan Kim Kee, the system of grassroots organisations in Singapore consisted mainly of CCCs, CCs/CCMCs and RCs/NCs. This system was initiated and supported by the PA. Therefore, although these NGOs could plan and organise activities by themselves, they had to follow the basic rules set by the PA. Residents of different races were welcome to participate in all activities, which had to be non-religious and non-political. Each grassroots organisation either organises activities by itself or cooperated with other organisations. (On 17 July 2008, I interviewed Tan Kim Kee, Group Director of Grassroots, at the PA.) ↩

-

Note: In the 1960s and 1970s, conflicts between different racial groups, especially between the Chinese and the Malays were a problem in Singapore. Leaders and members of the CCC were usually residents with influence in the society. Therefore, CCCs played an important role in promoting racial harmony and helping the poor. They took the initiative to volunteer and donate resources, and others followed suit. ↩

-

Note: According to Tan Kim Kee, NCs were formed in 1998. ↩

-

Note: PA staff worked at the CCs. ↩

-

People’s Association Neighbourhood Committee Rules and Regulations (amended, 15 September 2007), https://www.onepa.gov.sg/rules-and-regulations. ↩

-

Note: In Singapore, Members of Parliament hold MPS every month, to help citizens resolve any problems they had. For example, at Potong Pasir, MPS is held every Thursday at 7.30pm at the void deck of Block 108 void deck. Help provided by the MPs takes many forms, ranging from suggesting solutions to family discord, obtaining financial support in cases of emergency, to helping people obtain employment. The MPs explain government policies to the people as well, gather feedback, and channel the people’s concerns to political leaders. MPs also visit people’s homes regularly to see if they can offer any help and find out how they live. Grassroots organisations’ network is supported by the PA, and is an important part of the PAP administrative system. MPS is organised by PAP and not by any grassroots organisation. ↩