Why Politicians Don’t Stay? Making Sense of Critical Political Events in Post war Asia

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow Tay Thiam Chye presents a framework to understanding complex Asian politics.

Critical political events are high-impact events that will change the political trajectory of a nation. Asia comprises nations with a range of political systems with different political dynamics. Some nations experience frequent changes of political party control of the government while other nations have the same political party controlling the government for decades. The latter refers mainly to dominant party systems where one dominant party dominates many aspects of a nation’s political life for decades.

Recurrent news of factional crises or conflicts between key politicians within ruling political parties often sparks speculations of possible significant political changes. Nevertheless, these events have no great political impact unless a faction defects from the ruling party. This renegade faction can subsequently ally with the opposition parties to gain control of the government. Yet, such defections are rare events because factions face huge disincentives to defect from a ruling party. Factional leaders and members have to face huge political risks by giving up most of the prerogatives of ruling party members. This political risk is even greater in a dominant party system.

Nevertheless, these rare events cannot be explained adequately by current theories using either a political party or an individual politician as the unit of analysis. This paper uses the faction as the unit of analysis and reframes the analysis of a puzzling critical political event – factions defecting from a dominant political party – with a simple model. The framework posits that factional defection occurs only when the key factions are marginalised within the dominant party and expect to form the next government with the opposition parties. This model offers a framework to make sense of complex Asian politics.

The Context: The East Asian Economic Miracle, Strong Governments and Dominant Parties

Before the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, the “East Asia Economic Miracle” story depicted strong governments providing leadership in national economic development. Such governments were usually dominant party systems with a political party dominating the political scene for decades. Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) dominated Japanese politics for 38 years from 1955 to 1993. Its rule was associated with the rise of the Japanese economic miracle. Similarly, Taiwan’s Nationalist Party (Kuomintang; KMT) dominated the political scene from 1949 to 2000 and its rule was associated with rapid Taiwanese economic development. Together with South Korea, Hong Kong and Singapore, Taiwan was known as one of the “Four Asian Tigers”. In Southeast Asia, Malaysia’s United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) has also been associated with Malaysia’s rapid growth as one of the “Emerging Tigers” with Indonesia and Thailand. The trend of having dominant party systems is not unique to Asia. The Christian Democratic Party dominated Italy’s politics for more than four decades (1948–92) while the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) dominated Mexico’s politics for more than seven decades (1920s–2000). Other current and past dominant parties include Ireland’s Fianna Fail, Sweden’s Social Democrats, South Africa’s National Congress (ANC), and Israel’s Labor Party.

Despite dominating the political landscape of Asia for decades after the end of World War II, dominant parties have experienced different fates. On the one hand, most of these dominant parties have split and lost power. For instance, Indonesia’s Golongan Karya (Golkar) lost power in 1999, and Taiwan’s KMT lost control of the presidency to the Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) Chen Shui-bian in 2000. On the other hand, other dominant parties such as UMNO have remained in power. Significantly, among those parties that have lost power, some have regained power by relying on the decades of institutional advantage they have build up over the years. The Indian National Congress (INC) Party regained power in 1980 after losing the 1977 elections and Japan’s LDP regained power in 1994, less than a year after losing it in 1993.

The Puzzle and Weaknesses of Current Explanations

It is an axiom that a dominant party has to implode before the rules of the political game in the dominant party system can be changed. The key challenge is to answer why a dominant party implodes or splits. This paper uses the faction as the unit of analysis to complement the weaknesses of current explanations.

Current Explanation 1: Party Systems and Political Parties

From the political party level point of view, it seems counter-intuitive for a dominant party to lose power because its dominance is sustained by a positive cycle of dominance. Dominant parties control nearly all aspects of the political system (legislative and executive) hence there is almost no viable alternative government for voters to choose from. The fragmented opposition parties are unlikely to have the institutional power and experience to rule as effectively as the dominant party. Consequently, most dominant party systems persist due more to the weak and divided opposition parties rather than the dominant party’s effective governance.

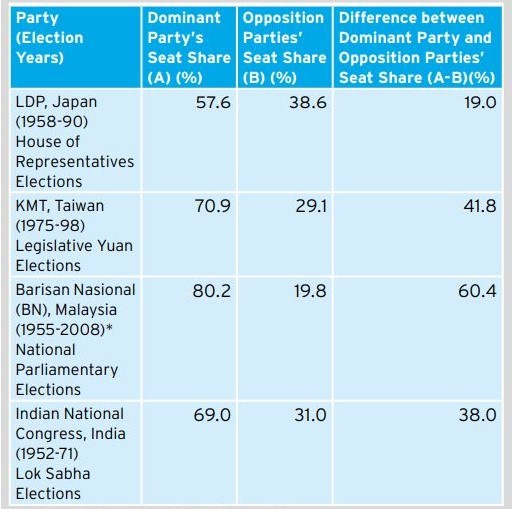

One of the most important factors for dominant party longevity is the power asymmetry between the dominant party and opposition parties. An aspect of this asymmetry is the huge seat share difference in the Lower Houses of Japan, Taiwan, India and Malaysia, ranging from 19.0% to 60.4% (Table 1). Using Taiwan as an example, opposition parties have two main options to gain power: win enough seats by their own efforts or merge with the much larger dominant party – KMT. For the former option, the opposition parties with only 29.1% of the seat share must win at least another 21.9% of seat share to secure at least a bare majority of 50% of the seats. This is not easily achievable because of KMT’s electoral dominance. With huge resources and support networks, KMT could easily mobilise votes and win more than 50% of the parliamentary seat share during elections. Even if the opposition parties win more than 50% of the parliamentary seats, they have to remain united. This is because the KMT can easily entice one or more opposition parties to merge with it or to form a ruling coalition. The latter option requires the least effort from any of the opposition parties but it does not serve KMT’s interest: the more politicians there are, the lesser the office spoils that could be shared among KMT members.

Table 1: Power Disparity between Dominant Party and Opposition Parties (Lower House)1

By using the political party as the unit of analysis, the dominant party split can be attributed to a multitude of factors in the political, economic and social arenas. The main argument is that exogenous macro-level factors create dire conditions at the national level thereby reducing the dominant party’s ruling legitimacy. The macro-level factors include ideology (Sasaki, 1999); democratisation (Giliomee and Simkins, 1999; Jayasuriya and Rodan, 2007); party system changes (Boucek, 1998); voter realignment (Reed 1999); changes of socioeconomic composition of the party’s support base (Pempel, 1998); entry of new parties (Greene, 2008); and/or changes in the values of the voters (Mair and Tomokazu, 1998). Nevertheless, the focus on exogenous factors ignores the dominant party’s intra-party dynamics and its adaptability. This being so, examining the cause of dominant party split at the macro-level provides only the context but not the precise causes and timing of party split.

Solinger (2001) argues that the presence of popular opposition party leaders and a great level of corruption are two of the causes of dominant party collapse. Nevertheless, these cannot explain situations in which all the factors were present but no dominant party lost power. There was corruption in Indonesia’s Suharto regime but why did the dominant party, Golkar, lose power after the 1999 elections but not in the previous elections? Popular opposition leaders have appeared at various stages during dominant party dominance but these politicians have failed to galvanise the opposition parties into common action to form new ruling governments. The popularity of Japanese opposition leader, Doi Takado, has failed to empower the largest Japanese opposition party, the Japan Socialist Party, to replace the dominant LDP. This being so, explaining party splits by using the party as the unit of analysis fails to account for this intra-party dynamics.

Current Explanation 2: Individual Politicians and Career Prospects

Moving the analytical lens down to individual politicians does not adequately explain party defection either. This explanation narrowly focuses on politicians and analyses the causes of party defection as a consequence of the individual politician’s aspiration to further his own political career.

Based on logical deduction, individual dominant party politicians are unlikely to leave the dominant party because it is the only party that is able to offer the fruits of power to them. These political benefits range from holding ministerial posts to having better access to state resources. Even if some politicians do not have the benefits at a point in time, they are likely to be better off remaining within the dominant party. This is because as long as the dominant party continues ruling, these politicians will have their turn in the share of political benefits. In contrast, the fragmented opposition parties in a dominant party system are very unlikely to form the new ruling government. Politicians face huge political risks when they leave a dominant party. They are likely to lose all the political benefits they have enjoyed in the dominant party with the worst-case scenario of losing their electoral seats. Losing seats often breaks a politician’s career. For instance, the failed “Janata Coalition Experiment” in India (1977–79) had showed the INC politicians of the 1980s the extreme difficulty in breaking down the “Congress System”. This institutionalised system of formal and informal norms has reinforced the INC’s dominance in national level Indian politics.2 This non-INC government soon collapsed as a result of intra-party disunity and within three years from losing power, the INC returned to power and continued its dominance of Indian politics.

Studies using the individual politician as the unit of analysis posit that a politician’s individual attributes determine the likelihood of him defecting from a political party. Cox and Rosenbluth (1995), in their analysis of the 1993 party defections in Japan, argue that junior and politically marginalised politicians are more likely to defect. This holds true if we treat politicians as lone wolves who act independently. However, this is not true in reality as this “strategically blind” approach ignores the greater context that shapes an individual politician’s decision making. Besides individual attributes, a politician needs to balance his individual needs with the organisational needs of the group to which he belongs. A group provides the essential political goods needed for a politician’s survival like funding for re-election campaigns and parliamentary posts. Extant literature, by focusing only on individual incentives, fails to account for a politician’s affinity for group incentives.

Alternative Approach/Explanation: Factions

This paper seeks to complement the two mainstream explanations by using the faction as the unit of analysis. Factions are sub-organisations within a political party that compete for political goods like political funding and parliamentary posts. Factionalism within parties has positive and negative impacts for dominant parties. Factionalism provides mechanisms to mitigate intra-party conflicts and thereby minimise the probability of dissent and dominant party members defecting. However, factionalism may create a vicious cycle of intra-party conflict that may eventually lead to greater party splits.

Compared with the two current explanations from the political party and individual politician perspective, it is more intuitive to understand dominant party defection from a factional perspective. While dominant party factions are generally better off by remaining within the dominant party than being part of a new unstable coalition government, factions do defect from the dominant party when two conditions are met. This paper argues that factional defection from a dominant party occurs when the key factions within the dominant party are marginalised in the inter-factional coalition game within the party and expect to win the future inter-party coalition game by forming a new government with the opposition parties. Unlike other factions, a key faction has a sizeable number of party members that allows it to form a winning inter-factional coalition in the party leadership competition.3 Thus, a dominant party faction’s potential to change the political landscape of a dominant party system makes it a rare event and different from the more commonly occurring party defections.4

Research Design: Model and Empirical Evidence

With the faction as the unit of analysis, this paper uses a model and narratives to verify three hypotheses. The model provides an internally consistent framework for systematic case comparison based on narratives. The narrative is based on the novel structured comparison of dominant party defection cases. This combination allows maximum analytical rigour and empirical richness to ensure robust findings.

The game theoretic model depicts the strategic interaction between two groups of actors in a dominant party: mainstream factions and non-mainstream factions.5 The model depicts two players interacting interdependently in the inter-party arena and intra-party arena. A key faction always has two main strategies: stay within the dominant party or defect from it. The predominant strategy is to remain within the dominant party because the faction can enjoy the fruits of power and continue factional struggle. The other strategy will be to defect from the dominant party and face the huge risk of losing political power.

Three hypotheses are derived from the game theoretic model:

• Hypothesis 1: A dominant party faction may not necessarily defect from a dominant party when the party has a relatively smaller Lower House seat share.

• Hypothesis 2: A dominant party faction is likely to defect from a dominant party when it is marginalised in intra-party competition.

• Hypothesis 3: A dominant party faction is likely to defect from a dominant party when the expectation of reduced coordination failure with the opposition party is high.6

Background

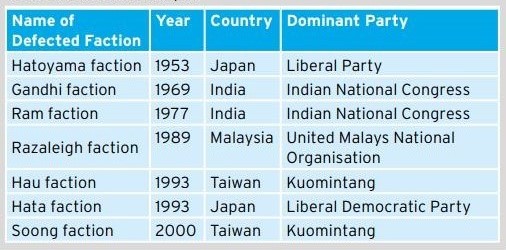

Table 2: Cases for Analysis

Narratives from historical events are used to test the model’s validity. As factional defections are rare political events, there are only seven party defection cases in the six decades of Asia’s political history since the end of World War II in 1945 (Table 2). These cases cover four dominant parties, LDP (Japan), INC (India), UMNO (Malaysia), and KMT (Taiwan). With the exception of Japan’s Hata factional defection, there is no systematic and comparative study of these rare but significant events.

The Liberal Party dominated Japanese politics in immediate postwar Japan from 1949 to 1953. The defection of the Hatoyama faction, led by Hatoyama Ichirō, ended the dominant Liberal Party’s rule in 1953. This faction formed the new Japan Democratic Party that subsequently formed the first non-Liberal Party government in 1954. Hatoyama Ichirō became prime minister of a minority government. The Japan Democratic Party eventually merged with the Liberal Party to form the current ruling LDP in 1955. LDP dominated Japanese politics for another three decades before the defection of the Hata faction ended its dominance. The Hata faction formed the Japan Renewal Party in 1993 and took the lead in forming a new seven-party government coalition. Contrary to conventional coalition theories, the LDP failed to form the new government despite being the largest political party, with 44.6% of the Lower House seat share. Ozawa Ichirō, the de facto leader of the Hata faction, remains a key politician in Japanese politics today.

KMT dominated Taiwanese politics from 1949 to 2000 until James Soong faction’s defection created the opportunity for Democratic Progressive Party’s Chen Shui-bian to become president in the 2000 presidential elections. The KMT presidential vote was split between James Soong and the official KMT presidential candidate, Lien Chan. Soong eventually formed the People First Party (PFP). A lesser known but significant factional defection from KMT occurred in 1993. The factional conflict was between the two largest KMT factions – the pro-Lee Teng-Hui mainstream faction (zhu liu pai) and the anti-Lee Teng Hui anti-mainstream faction (fei zhu liu pai), led by Hau Peitsun. Lee Teng-hui was then KMT chairman-cum-Taiwan’s president. While this factional defection did not immediately lead to KMT’s loss of power, it created the context and demonstration effect for future politicians seeking to break KMT’s dominance of Taiwanese politics.

UMNO had been dominating Malaysia’s politics since 1954. Various intra-party crises that centred on the struggle for intra-party presidency took place in UMNO throughout its dominance: the Sulaiman Palestin-Datuk Hussein Onn rivalry in the 1970s, the Razaleigh-Mahathir rivalry in the 1980s, the Anwar-Mahathir rivalry in the late 1990s and the Badawi-Mahathir rivalry in 2006 and 2008. Nevertheless, only one of these intra-party crises resulted in the defection of a faction from UMNO. This occurred in 1989, when Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah competed against then Prime Minister Mahathir bin Mohamad for the intra-party presidency. Allying with Musa Hitam (former deputy prime minister), Razaleigh formed a strong intra-UMNO factional coalition against Mahathir’s factions. Eventually, Razaleigh defected from UMNO and formed a new political party, Semangat 46.

INC dominated Indian politics continuously from 1947 to 1977. The faction, led by Indira Gandhi defected from the INC in 1969 after an intense intra-party conflict with the Syndicate factional coalition. Gandhi formed Congress-Requisition while the remaining INC formed Congress-Organisation. In 1977, another factional defection led by Jagjivan Ram split the INC again. Unlike in 1969, this critical political event ended INC’s dominance and brought about the formation of the first non-INC government in 1977. In a rare feat, almost all the opposition parties overcame the coordination failure and merged to form the Janata Party that eventually won the 1977 elections, thereby removing INC from power. Former important INC politicians like Jagjivan Ram, Morarji Desai, and Charan Singh played an important role subsequently in forming a non-INC ruling government.

Findings

All the hypotheses have been validated. A dominant party’s seat share does not have a definite impact on factional defection (hypothesis 1). The marginalisation of the faction in the intra-party arena (hypothesis 2) and the high expectation of reduced coordination failure with the opposition party in the inter-party arena (hypothesis 3) cause factional defection. This being so, based on hypotheses 2 and 3, this paper concludes that factional defection will occur only when the factions are marginalised in the factional competition and perceive an opportunity of political survival outside the dominant party.

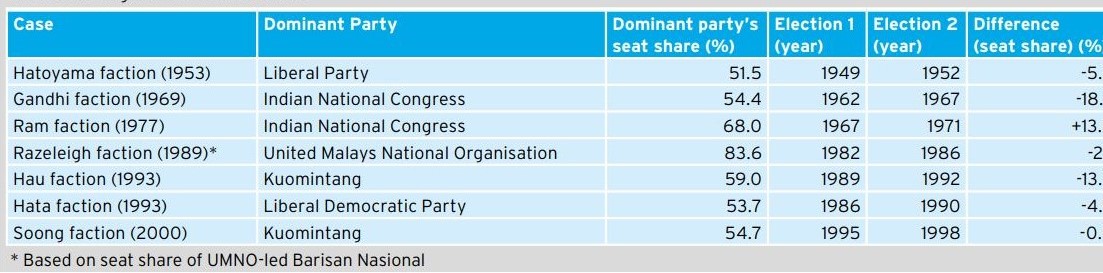

Table 3: Strength of Dominant Parties7

Hypothesis 1 is validated because a dominant party’s seat share does not have a definite impact on a dominant party faction’s decision to defect. In all the cases, the dominant party remained firmly in power with more than 50% of the Lower House seat share based on the results from the two most recent elections. There was a sharp decline in the dominant party’s Lower House seat share in two of the cases: the Gandhi case (1969) and Hau case (1993). The dominant party experienced only a slight drop in the Lower House seat share in the Razaleigh case (1989), the Hata case (1993) and the Soong case (2000). Only INC in the Ram case (1977) experienced an increase in the Lower House seat share.

Hypothesis 1 is counter-intuitive and contradicts the extant wisdom of the relationship between party defection and seat share; namely, politicians will defect from a declining party or politicians will defect from the dominant party with a slim majority. This makes sense because a waning dominant party opens a window of opportunity for renegade dominant party factions and opposition parties to foster cooperation in forming a new government. Nevertheless, this paper’s empirical results show that this is not always the case. The extant literature’s weaknesses arise because its focus only on the inter-party arena ignores the critical factional coalition dynamics in the dominant party’s intra-party arena.

For each case, the faction that defected was marginalised within the intra-party arena (hypothesis 2). These factions were usually one of larger factions, which had the potential to challenge the largest faction in the dominant party. The largest dominant party usually controls the key machinery of the dominant party, including the party presidency. The forms of intra-party marginalisation were mainly in the form of post-allocation and resource-allocation. Both resources are essential to maintain the factions’ power.

Finally, there was a high expectation of reduced coordination failure within the opposition party in the inter-party arena (hypothesis 3). This “high expectation” manifests itself in two main forms: an impending change in the rules of the political game at the national level and/or evidence of earlier successes of political cooperation between some renegade dominant party politicians and the opposition parties. Only the Ram case (1977) and the Hata case (1993) belong to the former category. In 1993, the call for political reform to change the rules of the game in Japanese politics was high on the political agenda of the political parties while in 1977 INC was discredited for its 1975–77 Emergency rule.

The rest of the cases belong to the second category. There were successful dissent actions by dominant party members in the 1953 Hatoyama case (e.g., voting for the punishment resolution of Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru in March 1953); the ability of the opposition parties to form successful electoral alliances in the 1967 Lower House elections created the context for political change in the Gandhi case (1969); for the Soong case (2000), the gradual moderation of the DPP and the decline of the New Party in the 1990s created the political context for reduction in coordination failure between renegade KMT factions and the opposition parties in Taiwan. Malaysia’s economic crisis in the mid-1980s created a conducive environment for the cooperation between UMNO’s renegade politicians and the opposition parties in the Razaleigh case (1989). The decreasing ideological distance between KMT non-mainstream factions and the main opposition party, the DPP created the context for the Hau case (1993).

So What?

This paper has shown how critical political events in Asian politics and dominant party factional defections can be understood with a simple model. Using a simple model substantiated by narratives, this paper argues that factional defection occurs only when the key factions within the dominant party are marginalised and expect to form the next government with the opposition parties. While this model explains only factional defection from dominant parties, its logic can be extended as a framework to make sense of Asian politics: to identify the key political actors (i.e., factions) and examine their cost-benefit calculations in the intra-dominant party and inter-party arenas.

For the public, the model provides a simple framework for making sense of complex Asian politics by examining the political actors’ (e.g., factions and politicians) strategic calculations in the inter-party and intra-party arenas. While news reports may highlight the idiosyncrasies of intra-party tensions and personality clashes between key politicians and/or highlight scenarios of the fall of a ruling party, a critical reader should make sense of Asian politics by examining the intra-party and inter-party dynamics simultaneously. For the former type of reports on political bickering, one has to identify if the renegade politician is a leader of a strong faction within the party. Without such political strength, the impact of such political bickering may be limited. In inter-party reports, one should assess if the parliamentary seat share difference between the ruling party and opposition parties is too great for any defection threats by a politician or faction to be credible.

Similarly, for Asian political analysts and observers, this model provides a conceptual anchor to make sense of contemporary Asian politics and to anticipate its future trajectories. Future events are always embedded in the present. This is exemplified by the historical antecedents of contemporary political events. The Democratic Party of Japan’s (DPJ) Ozawa Ichirō, one of the key politicians pushing for early elections in Japan in 2008, was part of the ruling LDP. In 1993, he led the Hata faction out of the LDP and eventually took the lead in forming a seven-party coalition government. He was subsequently in and out of various ruling government coalitions. Ozawa Ichirō still seems to be well poised to create another round of changes to the contemporary Japanese party system. Similarly, India’s current INC coalition government is plagued by the dual intra-INC and inter-party coalition tensions that have plagued INC since 1947.

A word of caution: past events are seldom good predictors of future events because politics in the real world is complex and emergent, shaped by complex adaptive agents like politicians. Thus, an analyst needs to identify the tipping points that precede the emergence of critical political events (e.g., the defection of a key faction from a ruling party or a coup). Such events or “black swans” can change the domestic politics and impact on the region (see Taleb 2007). A tipping point drawn from this paper’s model is the situation in which a renegade faction, marginalised within the dominant party, seeks to exploit an opportunity of reduced unity within the opposition parties.

Finally, there are two approaches for an academic wishing to further this paper’s research agenda: applying the model to other cases of dominant party factional defection and extending the model to explain other types of party defection. For the former, this model can be used to analyse cases of factional defection from dominant parties in nations like Italy, Mexico and South Africa. For instance, the Cárdenas factional defection from Mexico’s dominant party, PRI, in 1987 has similarities with the James Soong factional defection from KMT in 2000. In addition, this paper’s selection bias can be minimised by studying “non-events”, that is, events which should have occurred based on consistent and deductive logic but did not. For instance, before the coup in September 2006, Thaksin Shinawatra was able to maintain the Thai Rak Thai Party’s coherence. Surprisingly, despite intense factional competition, none of the big factions, like the Wong Nam Yam faction, defected from Thai Rak Thai Party. Another possible case will be the non-defection of factions from UMNO in the immediate period after the March 2008 elections. Such “non-events” will serve as useful case comparisons with factional defection cases.

For the latter, future research should extend the model to explain other types of party defections, that is, group defections and individual defections. One possible approach is to examine the interactions between the group level incentive structure and the individual level incentive structure. This paper focuses on the former while extant literature mainly focuses on the latter. In reality, party defections are based on a mixture of both types of incentive structures. Another approach is to use the complexity approach with the method of agent-based simulation. Like any typical game theoretic model, this paper’s model is static and tends towards equilibrium. This assumes that real world events follow linear trajectories, which are almost never true! Agent-based models have the potential to examine the interactions between different levels of analysis.

In short, understanding critical political events helps to shed light on the dynamics of Asian politics. Thus, use this simple model as a framework to make sense of complex Asian politics.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow

National Library

REFERENCES

Dorothy J. Solinger, “Ending One-Party Dominance: Korea, Taiwan, Mexico,” Journal of Democracy 12, no. 1 (January 2001), 30–42.

Francoise Boucek, “Electoral and Parliamentary Aspects of Dominant Party Systems,” in Comparing Party System Change, ed. Paul Pennings and Jan-Erik Lane (New York: Routledge, 1998), 103–24.

Gary W. Cox and Frances Rosenbluth, “Anatomy of a Split: The Liberal Democrats of Japan,” Electoral Studies 14, no. 4 (December 1995), 355–76.

Hermann Giliomee and Charles Simkins, The Awkward Embrace: One-Party Domination and Democracy (Australia: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1999). (Call no. R 321.9 AWK)

Horiuchi and Tay Thiam Chye, “Dynamics of Inter-Party and Intra Party Coalition Building: A Nested-Game Interpretation of Legislator Defection From a Dominant Political Party in Japan,” Policy and Governance Discussion Papers 04–02, Australian National University, September 2004, https://www.academia.edu/67237125/Dynamics_of_inter_party_and_intra_party_coalition_building_a_nested_game_interpretation_of_legislator_defection_from_a_dominant_political_party_in_Japan.

Kanishka Jayasuriya and Garry Rodan, “Beyond Hybrid Regimes: More Participation, Less Contestation in Southeast Asia,” Democratization 14, no. 5 (2007), 773–94.

Kenneth F. Greene, “Dominant Party Strategy and Democratization,” American Journal of Political Science 52, no. 1 (January 2008), 16–31. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Maurice Duverger, Political Parties (London: Methuen, 1954)

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (New York: Random House, 2007). (Call no. R 003.54 TAL)

Peter Mair and Tomokazu Sakano, Nihon Ni Okeru Sekai Saihen No Hoko [Japanese political realignment in perspective: Change or restoration], Leviathan 22 (1998), 12–23.

Steven R. Reed, “Political Reform in Japanese: Combining Scientific and Historical Analysis,” Social Science of Japan Journal 2, no. 2 (October 1999), 177–93. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

T.J. Pempel, Regime Shift: Comparative Dynamics of the Japanese Political Economy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998)

T.J. Pempel, ed., Uncommon Democracies: The One Party Dominant Regimes (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1990)

Takeshi Sasaki, Seiji Kaikau: 1800 Nichi No Shinjisu [Political reform: the record of the 1800 days]. (Tokyo: Kodansha, 1999)

Tay Thiam Chye, “Rethinking Dominant Party Defection: The Dual Coalition Dynamics of Factional Defection in Post-War Japan (1945–2003)” (master’s thesis, National University of Singapore, 2010), http://aunilo.uum.edu.my/Find/Record/sg-nus-scholar.10635-15528

NOTES

-

The figures are based on the average seat share won by the dominant parties in the Lower House elections within the specified period when the dominant parties were in power. ↩

-

The Janata Party, created from four main opposition parties, temporarily broke INC’s uninterrupted dominance of Indian politics by winning the 1977 elections. ↩

-

Indicators of key faction are that it has enough legislators to form a factional coalition to gain power within a dominant party and deprive the dominant party of its ruling majority in the parliament. ↩

-

Factional defection in this work differs from the more commonly occurring party defections from the opposition parties and minority ruling parties. ↩

-

Mainstream factions are groups within the dominant party, which mainly control the mechanisms of the dominant party while the non-mainstream factions are the opposing group of factions within the dominant party. For details of the model and research design, see Horiuchi and Tay (2004) and Tay (2005). ↩

-

Coordination failure can be failure to form a coalition or the failure to agree on a common prime minister candidate among the opposition parties. Generally, parliaments need to hold a vote to choose the prime minister after the elections. ↩

-

Election 1 refers to the last election that the dominant party has participated while Election 2 refers to the previous election the dominant party has participated. ↩