Journey to the West: Dusty Roads, Stormy Seas and Transcendence

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow Prasani Weerawardane traces the perilous journey from China to India over land and sea undertaken by Chinese Buddhist monks in search of the Buddhist Tripitaka.

This is a story of some of the greatest explorations of all time, journeys that resonate in the Asian cultural imagination. The road was the path from China to India, and the timeline stretches from the first century until the seventh century. Those who undertook this trip were Chinese Buddhist monks, looking to return with copies of the Buddhist Tripitaka.1 The term “road” is partly a misnomer, as it could also be a voyage by sea, via the merchant ships that ploughed the southern seas. Both land and maritime modes of travel were fraught with hazards, and could take the best part of a year to complete.

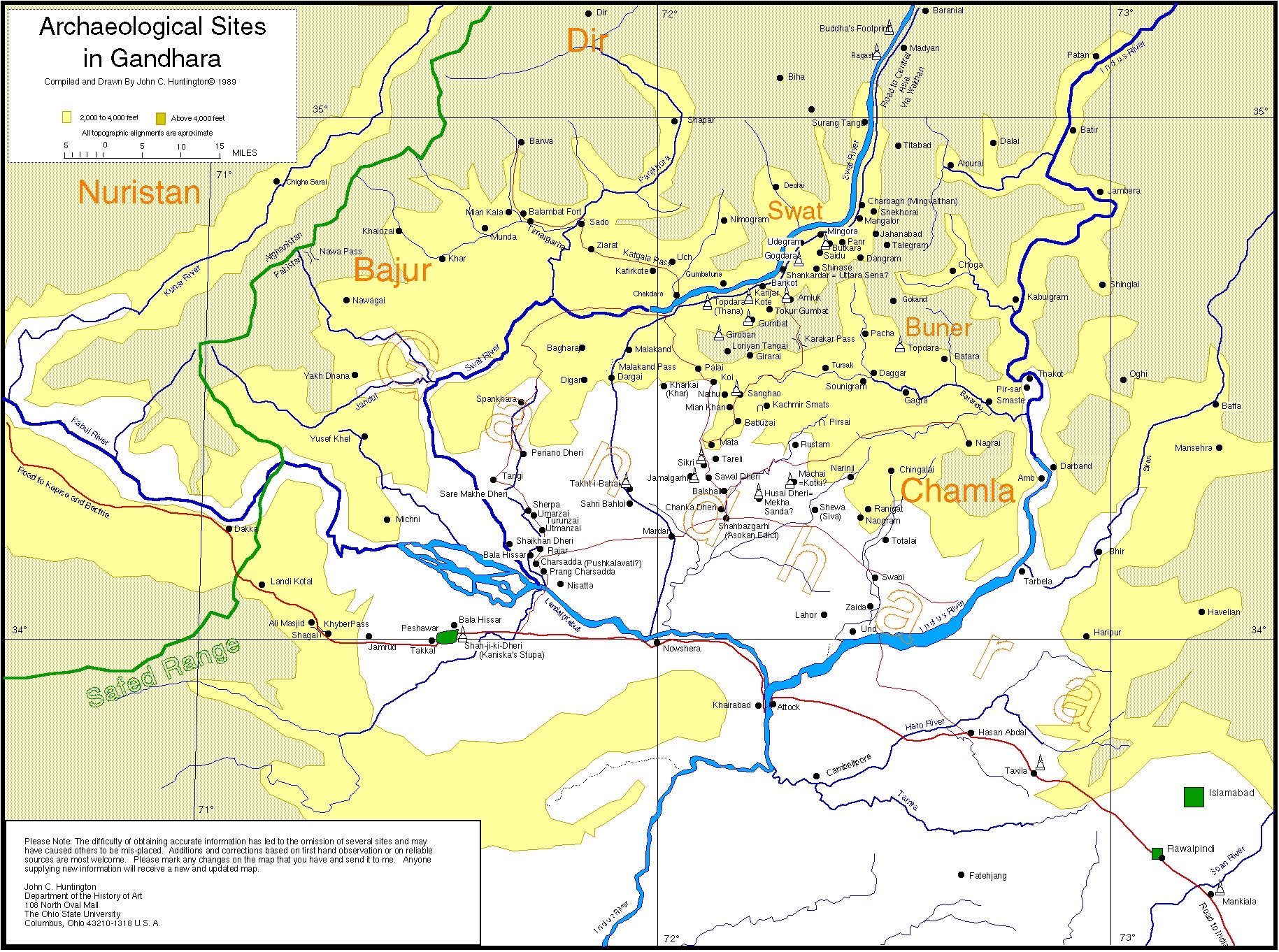

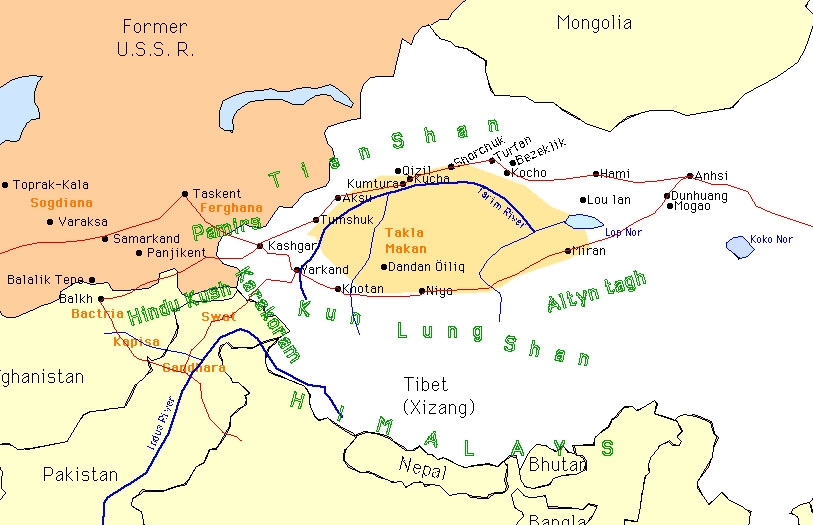

By land, one path followed the Silk Road west to Parthia and beyond, while another led southwest through a number of small central Asian states in uneven stages of civilisation. The hazards of both roads included the trackless desert wastelands of the Gobi and the high plateaus of central Asia, the tenuous and slippery mountain passes through the Himalayas, extreme weather conditions ranging from blistering heat to sub-zero temperatures, and encounters with unfriendly locals and bandits.

By sea, the dangers included leaking ships, raging storms, sudden squalls and typhoons, as well as deadly reefs.

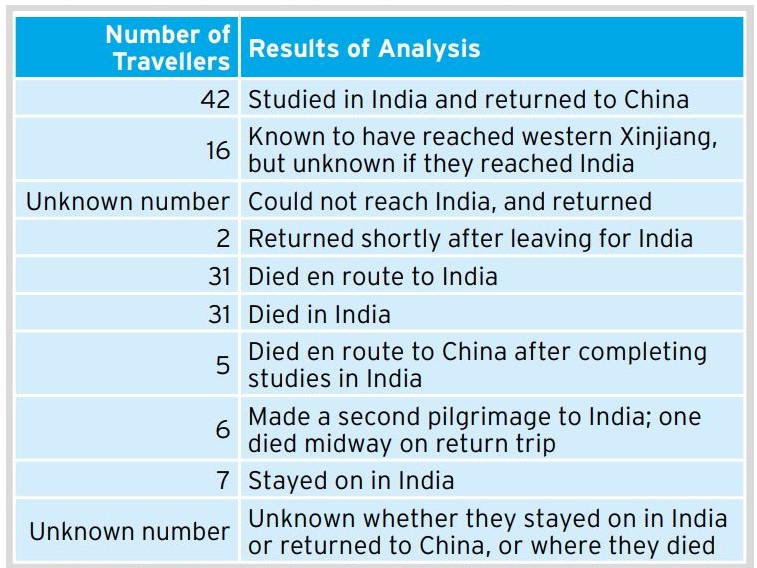

How many Chinese monks made this journey, and how many fell by the wayside? How many actually returned safely to China with the precious texts they went in search of? In a survey carried out in 1949, a Chinese historian delved through Indian archives and produced the following analysis of these travellers:

According to translated documents from the Bureau of Canonical Translations (Jan, 1966), a survey conducted during the Sung era also revealed that at least 183 monks made this journey back to China by the year 1035.

However, Ch’en Shu, the mayor of Chang’an, assessed that most of the monks wishing to go to India were “not well trained in their studies. They study only for a short period, and their manners are ordinary and ugly” (Ch’en Shu, 945–1002 CE). He therefore proposed that monks be made to take a canonical examination before they were allowed to travel to the west (Jan, 1966).

For these monks, the journey west was one of courage and hope bolstered by a faith sustained over time. They had dreams of learning more about Buddhism in India, and of bringing back those all-important Buddhist texts. Most of these intrepid monks went with nothing more than their clothes and a few personal belongings wrapped in a small bundle. Their determination is shown in this quote by the Chinese monk Yijing:

“A good general can obstruct a hostile army

But the resolution of a man is difficult to move.”

Despite the large number of Chinese monks who embarked on this adventure, only the accounts of three monks have survived:

Faxian (1886). A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: Being an Account by the Chinese Monk Faxian of His Travels in India and Ceylon (399–414 CE) in Search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline (J. Legge, Trans.). Islamabad: Lok Virsa.

Xuan Zang (2000). Si-yu-ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World: Translated from the Chinese of Hiuen Tsiang (629 CE) (S. Beal, Trans.). London: Routledge. (Original work published 1884).

Yijing (2005). A Record of the Buddhist Religion as Practiced in India and the Malay Archipelago (671–695 CE) (J. Takakusu, Trans.). New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. (Original work published 1896).

It should be noted that these texts are translations of the original accounts, and published many centuries after the travels had been completed. The veracity of these translated works must therefore be questioned, as highlighted by Jack Sewell:

Added to this is the tendency to romanticise the events of such ancient travels, and emphasise the exotic and wondrous sights and feats. Yet, as religious accounts, the writers were also bound by a responsibility to truth.

So while we may express some degree of scepticism when reading about threatening dragons and demons, or accounts of extraordinary miracles, we should not discount the real physical dangers and challenges that the monks had to endure throughout their journeys. Difficult terrains, shipwrecks, thirst and hunger were all genuine threats to the completion of their pilgrimages.

Faxian (c. 337–422 CE)

Faxian was a Buddhist monk from Shanxi, and his travel account (399–414 CE) is the oldest among the Chinese monks to have survived. Of the few monks who journeyed before him, very little information remains of their travels.

Orphaned at an early age, Faxian spent much of his life in Buddhist monasteries. He went to Chang’an (present-day Xi’an) to study Buddhism, but could not find sufficient materials on the Disciplinary Rules (vinaya) to help him. In 399 CE, he left for India with his friends, Huiking, Daoching, Huiying and Huiwei, to obtain a complete set of the Tripitaka. Together, they went to the Gobi desert, a place often described as treacherous:

It took them 17 days to cross the Gobi to Shenshen, a state now believed to be close to Lop Nor in Xinjiang. It is estimated that Faxian and his companions would have had to cover more than 40 kilometres a day in order to make the crossing in 17 days. He recorded that there were about 4,000 Buddhist monks of the Hinayana tradition in Shenshen. From there, Faxian and his companions went on to Khotan, a famous oasis city and district southwest of the Gobi, a very important Buddhist centre. They stayed in Khotan for three months before proceeding to Kashgar, another oasis city located in the Tarim Basin.

From Kashgar, Faxian went southwest towards the valley of the Indus River, where “the way was difficult and rugged, running along a bank exceedingly precipitous, which rose up there, a hilllike wall of rock. When one approached the edge of it, his eyes became unsteady. And if he wished to go forward in the same direction, there was no place on which he could place his foot; and beneath were the waters of the river called the Indus”.

After crossing the river, Faxian and his companions entered Udyana, or Swat, in northern Pakistan, where Buddhism flourished. From there they travelled to Gandhara and Taxila, and continued on to Purushapura (now Peshawar, the capital of the North-West Frontier province of Pakistan). Of the Karakoram Range, it was reported that “the snow rests on them both winter and summer. There are also among them venomous dragons, which, when provoked, spit forth poisonous winds, and cause showers of snow and storms of sand and gravel. Not one in ten thousand of those who encounter these dangers escapes with his life”.

At Purushapura, Faxian lost his friend Huiying, who fell ill and passed away. Another companion, Huiking, died in a cold, windy mountain pass on the way to Bannu in Punjab. Still, Faxian pushed on, and arrived on the plains of Madura in central India. Buddhism was flourishing in Madura, with many monasteries and monks. Faxian had an idealised dream of India, and his account is a vivid record of what he saw in Majjhima-desa (Middle Country in Pali):

Faxian travelled alone within India, learning Sanskrit and transcribing manuscripts, while his friend Daoching remained in the Middle Country. He travelled for 14 days on a merchant ship from Tamralipti, a port in western Bengal, and arrived at Lanka, where he spent the next two years. The capital of Lanka was Anuradhapura and Faxian extolled in detail the richness of the Buddhist influence in the city, as shown in their monasteries, a giant Jade statue of the Buddha, and their celebration of the holy tooth relic festival. He eventually returned to China by sea in 414 CE and took back with him many Buddhist texts.

Another of Faxian’s legacies is the valuable historical documentation of the Gupta empire under Chandragupta II (c. 375–415 CE). Considering that Faxian was nearing 60 years old when he left for India, his achievement is remarkable:

However, a common criticism of Faxian’s account is its lack of objectivity, unlike the texts of the other monks who travelled later. Although he is often seen as lacking the intellectual rigour of Xuanzang or Yijing, we cannot deny that his faith was unshakeable. In all, Faxian spent 15 years on his extraordinary journey, and passed away at the age of 88 at the Xin monastery of Jingzhou.

Xuanzang (c. 602–664 CE)

Xuanzang, the greatest and most famous of all the monks who journeyed to the west, was from the illustrious Tang dynasty of the seventh century.2 The Tang period was a watershed in Chinese cultural history, and gave rise to a flowering of literary culture and artistic expression. Xuanzang, born in this period, entered the White Horse monastery in Luoyang when he was 12, and received ordination as a monk in 622 CE3 He spent the next eight years studying and debating the doctrine, and realised that the imperfect translations of the original Sanskrit texts were impeding his understanding of Buddhism. Hence, he made a resolution to travel to the source of the religion.

Even though there was an imperial proscription forbidding any travel abroad, Xuanzang was not deterred. In 630 CE, he had a dream that he climbed Mount Sumeru, the holy mountain home of the gods, and that furthered convinced him to journey to India. Xuanzang, then 26 years old, began his journey from Suzhou. He was allowed to proceed as the governor, being a pious man, ignored an arrest order placed on him. However, his guide deserted him and Xuanzang was left to travel alone. The road west began with a dangerous river crossing as he would have to circumvent the guards at the Jade Gate that stood on the opposite bank as well as at five watch towers strategically located in the northwest direction. Moreover, “in the space between them there is neither water nor herb; beyond the five towers stretches the desert, (the Taklamakan) on the frontiers of the kingdom called I-gu”.

Xuanzang’s piety and determination impressed the guards at the watch towers, some of whom even provided him with advice on the best routes to take. Even so, while crossing the Taklamakan desert, he lost his water supply, and wandered around for the next five days without water. During those difficult times, he invoked the Heart Sutra, meant for those in dire straits, and was rewarded by a dream, which revived him. He soon found water and survived.

Xuanzang’s journey took him to Turfan in the Tarim Basin, as well as Yanqi and Kucha, kingdoms in northern Xinjiang. Crossing the Oxus River, he then made his way to Bactria (in Afghanistan). He described Balkh, the capital, as having about 3,000 Buddhist monks of the Theravada school, and many sacred relics of the Buddha. Further on at Bamiyan, he saw the two famous standing colossi of the Buddha, and a 1,000-foot-long reclining statue. When Xuanzang visited it, Bamiyan was an outstanding centre of the Gandharan school of Buddhist art.

Gandhara was famous for its Buddhist traditions and for producing eminent Buddhist scholars. At its capital, Purushapura (Peshawar), Xuanzang saw a stupa built by Kanishka, the great Kushan king, and a tower that held the Buddha’s alms-bowl.

In Kashmir, Buddhism was flourishing and there were about 5,000 monks. Xuanzang spent two years there studying Buddhist philosophy and transcribing sutras and texts to be taken back to China. From Kashmir, he then made his way to Mathura, where he saw the same stupas that Faxian had witnessed earlier.

Xuanzang spent 15 years studying and travelling throughout India. The highlight of his stay was his time at Nalanda, the famous Buddhist University at Bihar. Xuanzang first stayed at Nalanda for 15 months, studying philosophy and Sanskrit. After travelling within India extensively, he returned to Nalanda and studied there for many years, where he gained fame as a skilled debater and logician with his comprehensive knowledge of the Dharma.

Although his contemporaries at Nalanda tried to dissuade him from going back to China, Xuanzang returned in 645 CE, and devoted the rest of his life to the study and translation of the texts he had obtained. He had taken back a treasure trove of texts to China, a total of 657 titles, packed into 520 cases.

At the request of Emperor Taizong (626–649 CE), Xuanzang wrote his travelogue, and this remains one of his most important legacies. It documented the period of Buddhism in a state of decline in India, and gave a background to the passing of an age. In the early 20th century, Aurel Stein, a renowned archaeologist, rediscovered some of the kingdoms that Xuanzang visited and validated Xuanzang’s accounts.4 Xuanzang has achieved iconic status in Chinese Buddhism and is also immortalised as a folkhero in literature.5

Yijing (c. 635–713 CE)

Yijing’s text can be described as a geographical travelogue as well as an account of the state of Buddhism in India and Southeast Asia. Yijing was born in 635 CE during the reign of the Tang Emperor Taizong. He made the decision to travel to India when he was 18 years old and was ordained two years later. He was a great admirer of Faxian and Xuanzang, and embarked on his journey from Guangdong in 671 CE, sailing in a Persian ship. Yijing was possibly the first Chinese traveller to describe the maritime route from China to India:

He reached Srivijaya (present-day Sumatra) after 20 days, and studied Sanskrit there for six months. From Srivijaya, he went to Tamralipiti, a port in Bengal, where he met Dachengdeng, a disciple of Xuanzang. Together with some merchants, they went on foot towards Bihar. Along the way, however, Yijing fell ill and lagged behind the others and was attacked by robbers who took all his clothes and left him naked. Covering himself with mud and leaves, Yijing continued walking through the night and was able to rest only when he reached the village where the rest of his party stopped.

They reached Nalanda the next day, and Yijing remained there for 10 years. He was a great observer, and his detailed accounts of the monastic life and rituals at Nalanda are unparalleled. Yijing’s records provide us with a comprehensive picture of what it was like to be a Buddhist monk in the great Indian monastic centres.

Yijing’s geographical descriptions of the region, particularly Southeast Asia, also focus on the role of Buddhism in those kingdoms. The predominant form of Buddhism in Srivijaya was of the Hinayana (Theravada) tradition. His descriptions of the Malay Peninsula showed that it had many trade centres and a thriving maritime network. Other kingdoms in Southeast Asia such as Dvaravati and Langasuka in Thailand and Prome in Burma, were also described or alluded to. All these accounts add to the current state of Southeast Asia’s historical knowledge.

Yijing wrote another treatise called “Monks of the Buddhist Faith Who Went to the Western Country under the Tang Dynasty”. In it, he detailed the accounts of 51 monks from China who travelled to India during the Tang period and described the hardships and privations borne by them as well as their admirable spirit and desire for learning.

Yijing left India for China in 685 CE by ship but disembarked at Srivijaya instead, where he spent his time translating 400 Sanskrit works that he had taken with him.

He finally returned to China only in 695 CE before his final passing in 713 CE, he had with the help of nine Indian monks completed 56 translations in 230 volumes.

Contributions

The three accounts described the great Buddhist monasteries of India such as Nalanda, Vickramasila, Valabhi and Somapura. Nalanda in Bihar was one of the most famous institutions of learning in the Buddhist world from the seventh century until its destruction by Turushka invaders. All three monks documented the Buddhist monasteries as centres of learning with libraries of manuscripts. Xuanzang described the libraries of the Jetavana monastery at Buddhagaya as “richly furnished, not only with orthodox literature but also with Vedic and other non-Buddhistic works, and with treatises on the arts and sciences taught in India at the time”.

All three travellers also gave a broad spectrum of perspectives on the different aspects of Buddhism, from its evolution to its decline in India. They provided invaluable insights into the states and kingdoms of those times, and many of these kingdoms now remain only in such accounts.

Archaeology may have unveiled some of the mysteries of these ancient kingdoms, such as Karashar and Kizil in the Gobi, or Borobodur in Java, but we can only imagine the days of their glory as the monks saw and described them.

With Yijing’s passing, the era of travel writing ended and would not become popular again until the arrival of Marco Polo and other travellers from the West. Even so, these new visitors were not like the Chinese monks, who were bound by faith and belief in the Dharma.

From Faxian to Yijing, the travel accounts spanned a period of almost three centuries and gave a glimpse of the ages long removed by the sweep of history. Through their personalities and vivid descriptions, these writers have helped to bring those ages back to life. Perhaps more than anything else, they bring to us, at the beginning of the 21st century, the awareness of a rich and diverse Asian cultural heritage that has transcended time and place.

The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Dr Robert Knox, Former Keeper, Oriental & Islamic Antiquities, The British Museum, in reviewing the paper.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow

National Library

REFERENCES

Dilip K. Chakrabarti, “Buddhist Sites Across South Asia As Influenced by Political and Economic Forces,” World Archaeology 27, no. 2. (October 1995), 185–202. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Faxian, A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: Being an Account by the Chinese Monk Fa-Hien of His Travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399–414) in Search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline, trans. James Legge (Islamabad: Lok Virsa, 1886). (Call no. R 294.3438 FAH)

Hans-J. Klimkeit, “Buddhism in Turkish Central Asia.” Numen 3, no. 1 (June 1990), 53–69. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Jan Yun-Hua, “Buddhist Relations Between India and Sung China,” History of Religions 6, no. 2 (November 1966), 135–68. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Kanai Lal Hazra, Buddhism in India As Described by the Chinese Pilgrims, AD 399–689 (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1983). (Call no. RUR 294.30954 HAZ)

Mishi Saran, Chasing the Monk’s Shadow: Journey in the Footsteps of Xuanzang (New Delhi: Penguin Viking, 2005)

Rekha Daswani, Buddhist Monasteries and Monastic Life in Ancient India: From the Third Century BC to the Seventh Century AD (New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan, 2006). (Call no. R 294.36570954 DAS)

Richard B. Mather, “ Chinese and Indian Perceptions of Each Other Between the First and Seventh Centuries,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 112, no. 1 (January–March 1992), 1–8. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Sukumar Dutt, Buddhist Monks and Monasteries of India: Their History and Their Contribution to Indian Culture (London: G. Allen & Unwin, 1963). (Call no. RUR 294.3657 DUT)

The Life of Xuanzang, trans. S.B.K. Paul (London: Trench, Trubner & Co., 1911)

Walter Liebenthal, “Chinese Buddhism During the 4th and 5th Centuries,” Monumenta Nipponica 2, no. 1 (1955), 44–83. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Xuan Zang, Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World : Translated From the Chinese of Hiuen Tsiang (A.D. 629), trans. Samuel Beal (London: Routledge, 2000). (original work published 1884) (Call no. R 954.02 SIY)

Yijing, A Record of the Buddhist Religion As Practiced in India and the Malay Archipelago (A.D. 671–695), trans. J. Takakusus. (New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, 2005). (Original work published 1896) (Call no. R 294.363 YIJ)

NOTES

-

Sukumar Dutt, “The Collection of Buddhist Texts in China Translated from Sanskrit,” in Buddhist Monks and Monasteries of India: Their History and Their Contribution to Indian Culture (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas, 2000) ↩

-

Mishi Saran, “The Glorious Tang Dynasty Which Lasted for Three Centuries, and Heralded a Golden Age of High Culture in China From 626CE,” in Chasing the Monk’s Shadow: Journey in the Footsteps of Xuanzang (New Delhi: Penguin Viking, 2005) ↩

-

“The White Horse Monastery, where Buddhism is supposed to have begun in China was built by the Han Emperor in 67CE: many famous names were associated with Loyang, such as the Indian monk Bodhiruci, who arrived here in 508CE to translate texts, and Paramartha, another Indian monk who translated key Mahayanist texts” in Saran, Chasing the Monk’s Shadow, 563–67; Dutt, Buddhist Monks and Monasteries of India. ↩

-

“One of the greatest and most controversial names in Central Asian archaeology of the early 20th century. Hungarian by birth, British by inclination, Stein followed Xuanzang’s tracks across the Gobi, alluding to the monk as his mentor. In doing so, Stein validated much of Xuanzang’s travelogue, excavated diligently and rediscovered hidden treasures, such as the cave complex at Dunhuang, which yielded enormous quantities of scripts, paintings and scrolls, which are still being researched. There is now an international Dunhuang Project at the British Library, which is online, with many images digitised. This database utilises Stein’s and other materials from Central Asia” in International Dunhuang Project, British Library, http://idp.bl.uk/. ↩

-

Mishi Saran. See author’s notes. “In the sixteenth century, Wu Chengen created a mythical journey titled Journey to the West, incorporating a monkey king, based on Xuanzang’s epic trip. This account has now entered Chinese folklore with many in China confusing Xuanzang and the fictional monk. There was a translation by Arthur Waley into English in the 20th century, and the story has been serialised many times in cinema, TV and animation,” in Chasing the Monk’s Shadow. ↩