An Overview of Singapore’s Education System from 1819 to the 1970s

Through government reports and reviews held at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library, Librarian Wee Tong Bao traces the evolution of Singapore’s education system.

Among the little-known national treasures on the shelves of the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library is a large collection of government reports and reviews on various subjects. One subject on which the Library has a wealth of documents and tracts is the history of Singapore’s education system. When the policies and inquiries that had been published from the founding of modern Singapore till 1978 are examined chronologically, one can see the evolution of Singapore’s education system – from a laissez-faire arrangement to a nationally centralised system by the late 1970s.

In the beginning, British administrators were concerned only with providing primary education in the schools they had established. Missionaries and communal leaders had also set up schools of their own using money that the government provided, in the form of “grants-in-aid”. From 1870 till the start of World War II, the colonial government paid more attention to the island’s schools when it commissioned inquiries into the different aspects of education. Many committees were formed to review teaching and other aspects of the education system in the English and Malay vernacular schools. Reports were written on how funds were disbursed to schools, recommendations for the curriculum for government Malay vernacular schools as well as the provision of tertiary education in the English school system. Many of these reports were later named after the respective chairpersons heading the inquiries.

The Education System before World War I

The founder of Singapore, Stamford Raffles, professed:

The British presence on the island was represented by the East India Company, which was mainly concerned with trade. This being so, the British administrators initially focused on commerce, leaving most of the other social concerns such as education to the different communities on the island. In 1858, the colony, along with two other settlements (Penang and Malacca) in the Malacca Strait, was put under the control of the Governor-General of India. The administrators maintained their laissez-faire approach to education in the Straits Settlements. Things begin to change with the transfer of oversight from the India Office to the Colonial Office in London in 1867. The new British administration became actively interested in the affairs of the Straits Settlements and forced various committees to look into various sectors. In 1870, the Woolley Committee compiled a report on the state of education in the colony.1 In 1872, the position of inspector of schools was created to take charge of educational matters in the Straits Settlements. The first person to fill this position was A.M. Skinner.2

After the publication of the Woolley Report in 1870, another committee chaired by E.E. Isemonger was formed to look into the state of vernacular education in the colony.3 The impetus for this inquiry was the depressed trade conditions in the 1890s as a result of which the administration wanted to find out how best to expend the decreased revenue. The Isemonger Report was completed in 1894. Subsequent committees tasked to review and make recommendations concerning the disbursement of grants produced the “Report of the Committee appointed by His Excellency the Governor and High Commissioner to consider the working of the system of Education Grants-in-Aid introduced in 1920 in the Straits Settlements and the Federated Malay States“ by E.C.H. Wolff in 1922 and the “Report of the Committee to Consider the System of Grants-in-Aid to Schools in the Straits Settlements and the Federated Malay States” by F.J. Morten in 1932.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the British administrators wanted to find out more about the education that was being provided, especially post-primary and technical education. This was almost one century after they founded the Singapore Institution (later renamed Raffles Institution) in 1823 to educate the children on the island. The government had provided only primary education up to then, and the British rulers felt that it was time to consider post-primary education in the form of secondary or technical education. In 1919, a committee led by F.H. Firmstone was formed to propose the groundwork necessary for the “advancement of education preparatory to a University in Singapore”.4 The “Report of the Commission appointed by the Secretary of State for the Colonies on Higher Education in Malaya” (McLean Report) followed in 1939. The main objective of this report was to assess the Malay education that had been provided and to propose how higher education could be introduced. Another objective of the McLean committee was to look into the conferment of degrees to graduates of Raffles College and King Edward VII College of Medicine as there was increasing dissatisfaction that the certification was not recognised by many organisations as full degrees.

It was around this time that the British rulers felt that the system of education in the Straits Settlements needed a new focus, once they realised that many students were not able to find jobs as clerks in the government service or with private companies. Several committees were commissioned between 1917 and 1938 to review and make recommendations on vocational and industrial education, which would equip students with practical skills. Four known reports on vocational and industrial education were published during this period. R.O. Winstedt conducted two such inquiries in 1917 and 1925. Winstedt reviewed vernacular and industrial education in the Netherlands East Indies in 1917 and recommended that government Malay schools teach “three basic subjects of reading, writing and arithmetic, [with] special attention… to the Malay traditional pursuits of husbandry and handicraft”.5 The objective of his second review in 1925 was to determine the viability of industrial and technical education in Singapore, which built on the Lemon Report of 1919, a study of technical and industrial education in the Federated Malay States before the implementation of a higher education system in the colony.

It was the 1925 Windstedt Report that convinced the government that the Federated Malay States and the Straits Settlements were both ready for vocational training. In 1927, B.W. Elles was asked to plan for a school of agriculture, and to recommend the courses to be taught there. Vocational education was further supported by the publication of “Report on Vocational Education in Malay” by H.R. Cheeseman in 1938. Cheeseman’s committee recommended increasing the number of trade schools, introducing workshop craft for boys and domestic science for girls, including science in the curriculum of all secondary schools, and emphasised the “importance of gardening in schools and of agricultural training for vernacular school teachers”.6

It must be noted at this juncture that much of the curricular “reform” or “rethinking” of the Education Department concentrated on Malay and English education because the Malayan Government had little control over Chinese schools. Hence, the official reports and reviews published during this period placed a strong emphasis on vocational and technical education for Malay students in the government Malay primary schools throughout Malaya.

Political Influences on Education Policies Before World War II

Education policies before World War II were not formulated solely with the economic situation in mind. The government was also influenced by political forces. For example, the 1920 Schools Registration Ordinance not only marked a big step forward in British direct involvement with the education of all children in Singapore, it also heralded the end of the British non-interference approach towards Chinese vernacular schools. With this ordinance, the local government sought to “gain control over all schools in the Colony”. The government officially declared the following:

Although the ordinance applied to the island’s mission, government and other schools, it was introduced also as a result of the sociopolitical conditions prevailing in 1919 and 1920. Many local Chinese were caught up with the political upheaval in China, exacerbated by the unfair terms of the Versailles Peace Conference, which ceded Shandong to Japan. A number of students and teachers in Malaya organised demonstrations and boycotted Japanese goods in protest. In Singapore, mass demonstrations and open violence broke out on 19 June 1919. Demonstrators attacked Japanese shops and destroyed Japanese goods. In response, the British authorities declared martial law.7 These disturbances disrupted the economic progress of Singapore and the rest of British Malaya, and Chinese students and teachers were identified as the key agitators in these incidents.

The ordinance was first presented as the Education Bill to the Straits Settlements Legislative Council on 31 May 1920. It met with strong objections from some factions of the Chinese community, which felt that the government’s attempt to remove the political element from Chinese education was as good as putting an end to Chinese vernacular education. They were “full of fear and suspicion”, and sent their petitions through Lim Boon Keng, the Chinese representative of the Straits Settlements Legislative Council. Despite their objections, the ordinance was eventually passed in October 1920.8

Under this ordinance, managers and teachers of schools were required to register with the Education Department within three months for existing schools, and one month for new schools. Any changes in the teaching staff or committee of management of the registered schools had to be reported to the Education Department within one month. Every registered school also had to be inspected by the director of education, who was empowered to declare schools unlawful if there was any evidence of involvement in political propaganda detrimental or prejudicial to the interests of the colony.9 The ordinance and the general regulations were first amended in 1925, and were repeatedly amended to ensure compliance and effectiveness.

Postwar Development

When World War II ended, Singapore returned to British rule once again. On 7 August 1947, a “Ten-Year Programme” was established. This was meant to be the “basis for future educational development in the Colony of Singapore”.10 The general principles outlined in this policy were “foster[ing] and extend[ing] the capacity for self-government, and the ideal of civic loyalty and responsibility; … [providing] equal educational opportunity to the children – both boys and girls – of all races, … upon a basis of free primary education there should be developed such secondary, vocational and higher education as will best meet the needs of the country”.11

As Singapore was still recovering from the devastation of the war, it was understandable that “the first priority (was) rehabilitation”.12 Much emphasis was given to primary education, though the scope of the policy also covered areas such as post-primary education in the English and vernacular schools, training of teachers, administration and inspection of schools and the types of schools.13

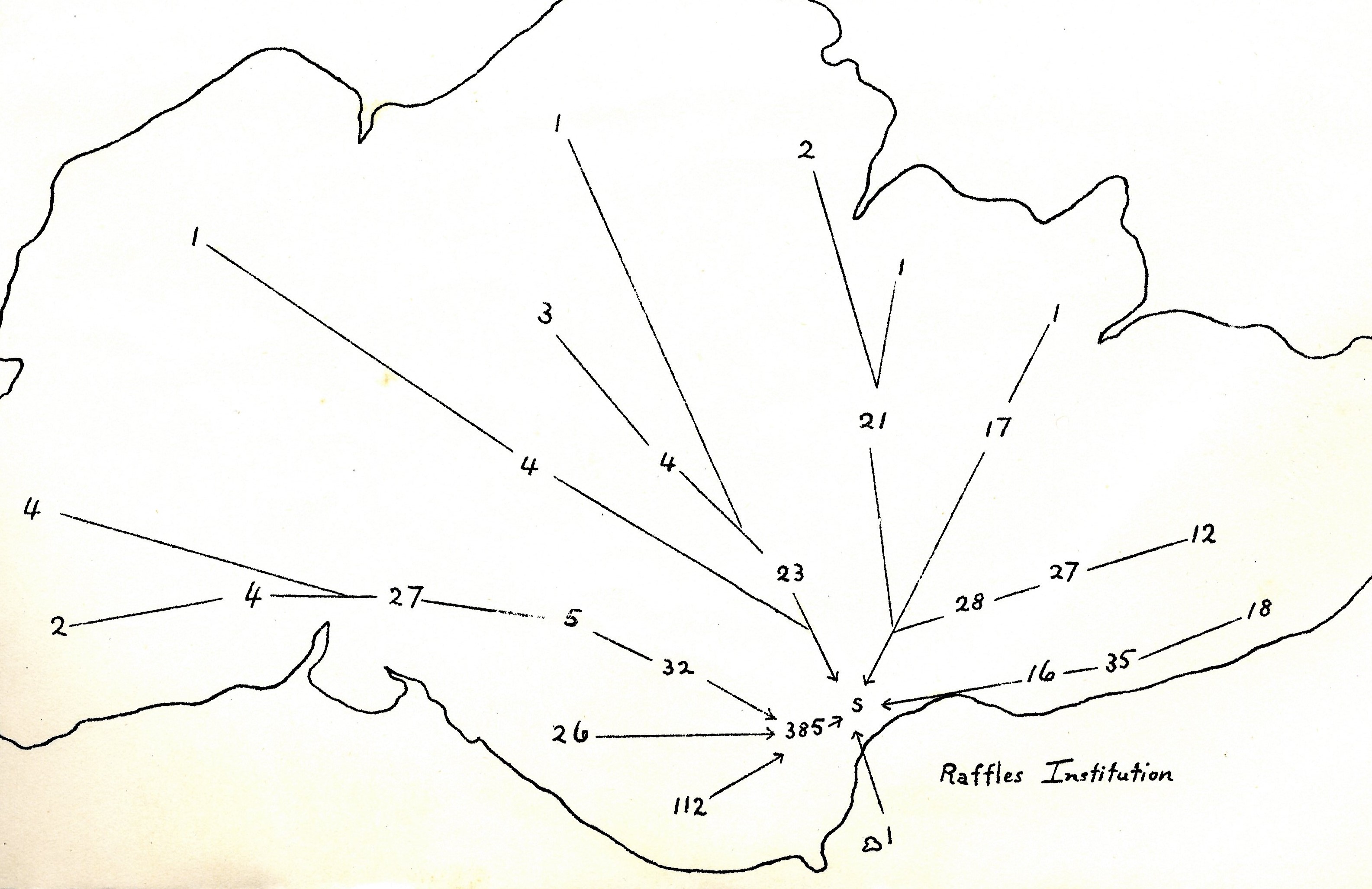

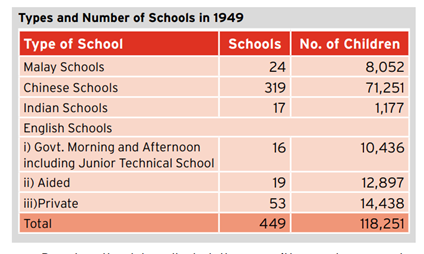

This policy also stressed that “the basis of all schools should be regional rather than racial, and should ensure the intermingling of pupils of all races in all the activities of school life”.14 To facilitate the implementation of the “Ten-Year Programme”, surveys were carried out throughout Singapore to determine the number of schools and pupils enrolled in each area. In total, 26 surveys were conducted, covering areas such as Jurong, Kranji and Lim Chu Kang in the west, Bedok, Tampines and Changi in the east, Sembawang and Seletar in the north, and New Bridge Road, South Bridge Road, Market Street, Raffles Place and Collyer Quay in the south. The surveys revealed that there were a total of 118,251 pupils in 449 schools at the time (see below).15

Based on the data collected, the committee made proposals about school facilities, capacity of existing schools and ways to support the new initiatives in the years to come. The report of the committee also included appendices showing the estimated annual increases in enrolment and expenditure from 1951 to 1960.

In 1955, the Ministry of Education was formally established. In the following year, two important documents on education were released: the “Report of the All-Party Committee of the Singapore Legislative Assembly on Chinese Education” followed by the “White Paper on Education Policy”. The White Paper built on the findings of the All-Party Committee Report, and highlighted the challenges faced by Singapore: “to reconcile those elements of diversity which arise from the multi-racial structure of its population”, and “to cope with the phenomenal increase in the population of school-going age”.16 To address the first challenge, the government decided on “build[ing] a Singapore or Malayan nationalism”. The paper explored how a “common Malayan loyalty” could be built in the schools. To underline its belief that the “education policy should be based on equal respect for the four principal cultures of Singapore”, the paper also proposed replacing the several legislation governing schools then – namely, Education Ordinance, 1948 (No. 22 of 1948), Registration of Schools Ordinance, 1950 (No. 16 of 1950) and Schools (General) Regulations, 1950 – with a single Education Ordinance that would apply to all schools.17 This was achieved with the passing of the new Education Ordinance in 1957. To meet the second challenge of increasing numbers of school children, it was proposed that the schools be expanded, and that more teachers should be trained.18

Throughout the 1960s, the government continued to pay attention to education – particularly vocational education – and ordered several more reviews. The impact that the type of education system had on the economy was of utmost interest to the government. With Singapore’s limited natural resources, the government realised that industrialisation would be the lifeline of Singapore’s economy, and thus “her human resources must be harnessed to the full”.19 A review led by Chan Chieu Kiat, the “Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Vocational and Technical Education in Singapore” (subsequently known as the Chan Chieu Kiat Commission) in 1961 suggested restructuring the secondary education system to accommodate vocational, technical and commercial education.20 So that students and teaching staff of vocational institutions could keep up with the advancements in their chosen fields, the commission also suggested that “the setting up of a technical and scientific section in the National Library deserved urgent consideration”.21

The 1961 Chan Chieu Kiat Commission was complemented by the “Commission of Inquiry into Education” led by Lim Tay Boh the following year. The terms of reference of this commission were to “inquire into the Government’s Education Policy, its content and administration in all fields other than vocational and technical education, and to make recommendations”.22 This inquiry, however, did not review the two universities. This commission submitted an interim report in 1962, and a final report in 1963. Some of the key recommendations of this commission included the adjustment of class size and pupil-teacher ratio for primary and secondary schools, revision of the Primary School Leaving Examination by aligning the examination syllabus to the teaching in the schools, training of teachers, allowance and remuneration of principals and teaching staff, as well as skills and facilities that could enhance students’ learning. Examples of recommendations made were: “all trainee teachers and some of the experienced teachers should be given training in librarianship”, and “the necessity to appoint a qualified School Library Adviser at the Ministry of Education”.23

The most significant review in the 1970s was the 1978 Goh Keng Swee Report on the state of education. This study, however, was not a formal commission of inquiry, and no terms of reference were spelt out for the team. Goh remarked that “the approach we [the team] take is that of the generalist, and not of the specialist” (1978 Report, p. ii).24The team highlighted key problems in the education system at the time, such as the preference for English-stream schools, the importance of bilingual education, the necessity of streaming students according to their learning capabilities, moral education syllabus and administration at the Ministry of Education.

This report had a far-reaching impact on the development of education in the years to come. In 1979, primary three pupils were streamed into Express, Normal or Monolingual classes. With the preference for English-stream schools, all the four language-stream schools were merged into English-stream schools, where lessons on all subjects were conducted in English except for the mother tongue (Chinese, Malay or Tamil), which students studied as a second language. This merger was reflected in the 1984 “Directory of Schools and Institutions”, in which schools were no longer classified by language stream. As shown in the Preface of the Directory:

The Ministry of Education also ensured that pupils who had the capability to study another language as a first language could continue to learn their mother tongue as a first language too. This was implemented under the Special Assistance Plan (SAP) in nine schools in 1979.

Conclusion

Singapore’s education system from 1819 to 1978 can be seen to have passed through three distinct phases. In the first phase, before the outbreak of World War II, there were other providers of education besides the British. The second phase took place after World War II, and was marked by the government’s concerted effort to centralise the curriculum to maximise scarce resources in the immediate postwar years. The third phase was heralded by the creation of a national school system after the nation’s Independence in 1965. The legacy of different language traditions continued into the early 1980s. Even without an official history of these developmental phases, the motley of policy papers and reports kept in the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library capture the evolution and details of these phases.25

Through the official reports and policies, one can see that the attempts by the government to exert control over all schools in Singapore were evident before World War II. The 1920 School Registration Ordinance can be considered to be the first such endeavour. Official reviews and inquiries were still being carried out along ethnic lines even after World War II. The following government reviews underscore this contention: “Report of the Committee on Malay Education” (Barnes Report) in 1951, “Report of a Mission Invited by the Federation Government to Study the Problem of Education of Chinese in Malaya” (Fenn Report) in 1951, “All-Party Committee on Chinese Education Appointed to Look into the Education Needs of Chinese Schools” in 1955 and the “Report of the All-party Committee on Chinese Education of the Singapore Legislative Assembly on Chinese Education” in 1956.

It was not till the 1957 Registration of School Ordinance that we see another attempt by the government to consolidate the numerous “micro-systems” that existed within Singapore’s education system. The main shift away from policies with communal considerations to those stressing national concerns took place after self-rule was attained. Some of these developments were captured in the 1961 “Commission of Inquiry into Vocational and Technical Education in Singapore” (Chan Chieu Kiat Commission) and in the 1962 “Commission of Inquiry into Education” (Lim Tay Boh Commission). The 1978 Goh Keng Swee Report recommended the merger of all four language-stream schools into a common English-stream system. All schools were transformed into English-medium schools by 1984. By then, it was no longer necessary to address educational issues peculiar to ethnicity and language stream as all policies and reviews subsequently applied to all Singapore schools.

If readers wish to explore the subject further, I recommended David Chelliah’s A History of the Educational Policy of the Straits Settlements with Recommendations for a New System Based on Vernaculars (1940) and Saravanna Gopinathan’s Towards a National System of Education in Singapore, 1945–1973 (1974). Both authors also consulted the resources that I have referred to in my article. Their works are available at Level 12 of the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library, National Library.

Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library

REFERENCES

All-Party Committee on Singapore Chinese Middle Schools Students’ Union, Singapore, Singapore Chinese Middle Schools Students’ Union (Singapore Legislative Assembly Command Paper Cmd. 53 of 1956) (Singapore: Printed at the Govt. Print. Off., 1956). (Call no. RCLOS 371.83 SIN; microfilm NL9547)

All Party Committee on Chinese Education, Singapore, Report of the All-Party Committee of the Singapore Legislative Assembly on Chinese Education (Singapore: Govt. Printer, 1956). (Call no. RCLOS 371.9795105957 SIN)

C.M. Turnbull, A History of Singapore, 1819–1988 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1989. (Call no. RSING 959.57 TUR)

Central Advisory Committee on Education, Malaya, Report on the Barnes Report on Malay Education and the Fenn-Wu Report on Chinese Education [Kuala Lumpur: Govt. Press, 1951) (Call no. RDTYS 371.979920595 MAL)

Commission of Inquiry into Vocational and Technical Education in Singapore, Singapore, Report of the Commission of Inquiry Into Vocational and Technical Education in Singapore (Singapore: Govt. Print. Off., 1961). (Call no. RCLOS 371.426 SIN; microfilm NL11766)

Committee on a Polytechnic Institute for Singapore, Singapore, Committee on a Polytechnic Institute for Singapore (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1953). (Call no. RCLOS 378.5951 SIN)

Committee on Malay Education, Malaya, Report (Kuala Lumpur: Govt. Press, 1951). (Call no. RCLOS 371.979920595 MAL; microfilm NL9546)

F.J. Morten and Straits Settlements, Report (Straits Settlements. Legislative Council Command Paper no. 103 of 1932) (Singapore: Printed at the Govt. Print. Off., 1932). (Call no. RRARE q379.12; microfilm NL7596)

Francis H.K. Wong and Gwee Yee Hean, Official Reports on Education: Straits Settlements and the Federated Malay States, 1870–1939 (Singapore: Pan Pacific Book Distributors, 1980). (Call no. RCLOS 370.95957 WON)

Goh Keng Swee and Education Study Team, Report on the Ministry of Education 1978 (Singapore: Printed by Singapore National Printers, 1979) (Call no. RSING 370.95957 SIN)

H.R. Cheeseman, Report on Vocational Education in Malaya (Singapore: Printed at the Govt. Print. Off., 1938). (Call no. RRARE 371.42 CHE; microfilm NL9821)

Legislative Assembly, Singapore, White Paper on Education Policy (Singapore Legislative Assembly Command Paper Cmd. 15 of 1956). (Singapore: Legislative Assembly, 1956). (Call no. RCLOS q370.95951 SIN; microfilm NL9547)

Legislative Council, Straits Settlement, Straits Settlements, Proceedings of the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements (With Appendices) for … (Singapore: Government Microfilm Unit, 31 May 1921). (Microfilm NL1120)

Lee Kuan Yew, New Bearings in Our Education System: An Address … to Principals of Schools in Singapore on August 29, 1966 (Singapore: Ministry of Culture, 1966). (Call no. RCLOS 370.95951 LEE; microfilm NL9547)

Lee Ting Hui, Chinese Schools in British Malaya: Policies and Politics (Singapore: South Seas Society, 2006). (Call no. RSING 371.82995105951 LEE)

Lim Tay Boh, Final Report (Singapore: Govt. Printer, 1964). (Call no. RCLOS 370.95957 SIN; microfilm NL15271)

Lim Tay Boh, Interim Report on the Six-Day Week (Singapore: Govt. Printer, 1962). (Call no. RCLOS 370.95957 SIN; microfilm NL9547)

Malaya, Memorandum on Chinese Education in the Federation of Malaya (Kuala Lumpur: Art Printing Works, 1954). (Call no. RCLOS 371.979510595 MAL; microfilm NL9546)

Member for Education, Malaya, Annual Report … on the Education Ordinance, 1952 (Malaya Federal Legislative Council Command Paper no. 29 of 1954) [S. l.: s. n., 1954]. (Call no. RCLOS 370.9595 MMEAR-[RFL]; microfilm NL9546)

Ministry of Education, Singapore, Annual Report (Singapore: Printed at the Govt. Print. Off., 1946–1967). (Call no. RCLOS 370.95951 SIN; microfilm NL9335)

Ministry of Education, Singapore, Directory of Schools and Institutions (Singapore: Education Statistics Section, Computer Services Branch, Planning & Review Division, 1982–1984). (Call no. RSING 371.00255957 DSI)

Ministry of Education, Singapore, Educational Policy in the Colony of Singapore: Ten Years Programme (Singapore: Ministry of Education, 1947–1949). (Call no. RCLOS 370.95951 SIN; microfilm NL4083)

Ministry of Education, Singapore, ETV Singapore (Singapore: Ministry of Education, 1966–1979). (Call no. RCLOS 370.95957 SIN)

Ministry of Education, Singapore, Singapore, Educational Policy in the Colony of Singapore: Supplement to the Ten-Year Programme: Data and Interim Proposals (Singapore: Ministry of Education, 1949). (Call no. RCLOS 370.95951 SIN)

Ministry of Education, Singapore, Singapore Government Press Statement (Singapore: Ministry of Education, 1966–1976). (Call no. RCLOS 370.95957 SIN)

Mission Invited by the Federation Government to Study the Problem of the Education of Chinese in Malaya, Malaya, Chinese Schools and the Education of Chinese Malayans: The Report of a Mission Invited by the Federation Government To Study the Problem of the Education of Chinese in Malaya (Kuala Lumpur: Govt. Press, 1951). (Call no. RCLOS 371.979510595 MAL)

Public Relations Office, Singapore, Education Week, May 8th–13th, 1950: The Steps to Success (Singapore: Published by Public Relations Office for the Dept. of Education, 1950). (Call no. RDTYS 370.95951 SIN)

Robert L. Jarman ed., Annual Reports of the Straits Settlements 1855–1941 ([Slough, UK]: Archive Editions, 1998). (Call no. RSING 959.51 STR-[AR])

Saravanan Gopinathan, Towards a National System of Education in Singapore, 1945–1973 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1974). (Call no. RSING 379.5957 GOP)

Singapore, Chinese Schools – Bilingual Education and Increased Aid (Singapore: Govt. Print. Off., 1953). (Call no. RCLOS 371.9795105957 SIN)

Sophia Raffles, Memoir of the Life and Public Services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991). (Call no. RSING 959.57021092 RAF)

Straits Settlements, Annual Departmental Reports (Singapore: Printed at the Govt. Print. Off., 1891–1938). (Call no. RRARE 354.595 SSADR; microfilm NL2927, NL2928, NL 25412)

Straits Settlements, Straits Settlements Government Gazettes (Singapore: Mission Press, 1858–1942). (Call no. RCLOS 959.51 SGG)

Straits Settlements, Report (Straits Settlements. Legislative Council Command Paper no. 45 of 1922) (Singapore: Printed at the Govt. Print. Off., 1922). (Call no. RRARE q379.12 STR; microfilm NL7548)

Straits Settlements. Technical Education Committee, Report, 1925 (Singapore: Technical Education Committee, 1925). (Call no. RRARE 607.5951 STR; microfilm NL7596)

T.R. Doraisamy et al., 150 Years of Education (Singapore: TTC Publications Board, Teachers Training College, 1969). (Call no. RSING 370.95957 TEA)

Yeo Hailin, “The Registration of Schools Ordinance of British Malaya, 1920: Origins and Outcome,” (Bachelor’s Thesis, National University of Singapore, 1990, https://scholarbank.nus.edu.sg/handle/10635/166959

NOTES

APPENDIX: A Select List of Education Policies and Papers from 1819 to the 1970s

1870: Report of the Select Committee of the Legislative Council to Inquire into the State of Education in the Colony (Woolley Report)

1894: Report of the Committee Appointed to Inquire into the System of Vernacular Education in the Colony (Isemonger Report)

1902: Report of the Commission of Enquiry into the System of English Education in the Colony (Kynnerseley Report)

1917: Report on Vernacular and Industrial Education in the Netherlands East Indies and the Philippines, by R.O. Winstedt

1919: Report by the Committee Appointed by His Excellency the Governor to Advise As to a Scheme for the Advancement of Education Preparatory to a University in Singapore (Firmstone Report)

1919: Report of the Committee on Technical and Industrial Education in the Federated Malay States (Lemon Report)

1922: Report of the Committee Appointed by His Excellency the Government and High Commissioner To Consider the Working of the System of Education Grants-in-Aid Introduced in 1920 in the Straits Settlements and the Federated Malay States (Wolff Report)

1925: Report of the Technical Education Committee (Winstedt Report)

1927: Report of the Committee Appointed to Draw Up a Scheme for a School of Agriculture as a Joint Institution for the Federated Malay States and Straits Settlement (Elles Report)

1928: Proceedings of the Committee Appointed by His Excellency the Governor and High Commissioner To Report on the Question of Medical Research Throughout Malaya. (Command Paper – Straits Settlements. Legislative Council; No. 13 of 1929)

1932: Report of the Committee to Consider the System of Grants-in-Aid to Schools in the Straits Settlements and the Federated Malay States (Morten Report) (Command Paper – Straits Settlements. Legislative Council; No. 103 of 1932)

1938: Report on Vocational Education in Malay, by H.R. Cheeseman

1939: Report of the Commission Appointed by the Secretary of State for the Colonies on Higher Education in Malaya (McLean Report)

1947–1949: Educational Policy in the Colony of Singapore: Ten Years Programme (Vol. 1) and Supplement to the Ten-Year Programme: Data and Interim Proposals (Vol. 2)

1951: Report of the Committee on Malay Education (Barnes Report)

1951: Chinese Schools and the Education of Chinese Malayans: The Report of a Mission Invited by the Federation Government to Study the Problem of the Education of Chinese in Malaya (Fenn Report)

1951: Report on the Barnes Report on Malay Education and the Fenn-Wu Report on Chinese Education

1953: Chinese Schools – Bilingual Education and Increased Aid (Command Paper – Singapore. Legislative Council; Cmd. 81 of 1953)

1953: Report of the Committee on a Polytechnic Institute for Singapore

1956: Singapore Chinese Middle Schools Students’ Union (Command Paper – Singapore. Legislative Assembly; Cmd. 53 of 1956)

1956: Report of the All-Party Committee of the Singapore Legislative Assembly on Chinese Education (Led by Chew Swee Kee)

1956: White Paper on Education Policy (Command Paper – Legislative Assembly; Cmd. 15 of 1956)

1961: Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Vocational and Technical Education in Singapore (Chan Chieu Kiat Commission)

1962: Interim Report on the Six-Day Week – Commission of Inquiry Into Education (Lim Tay Boh Commission)

1964: Final Report – Commission of Inquiry Into Education (Lim Tay Boh Commission)

1979: Report on the Ministry of Education 1978 (Prepared by Goh Keng Swee and the Education Study Team)

-

Doraisamy, 150 Years of Education, 26. ↩

-

Doraisamy, 150 Years of Education, 26. ↩

-

Wong and Gwee, Official Reports on Education, 66. ↩

-

Wong and Gwee, Official Reports on Education, 66. ↩

-

Straits Settlements. Technical Education Committee, Report, 1925 ↩

-

Cheeseman, Report on Vocational Education in Malaya. ↩

-

Yeo, “Registration of Schools Ordinance,” 32–34. ↩

-

Lee, Chinese Schools in British Malaya, 89–104. ↩

-

Straits Settlements, Straits Settlements Government Gazettes, no. 21 (29 Oct 1920), sections 10, 11, 18 and 19. ↩

-

Ministry of Education, Singapore, Educational Policy, 5. ↩

-

Ministry of Education, Singapore, Educational Policy, 5. ↩

-

Ministry of Education, Singapore, Educational Policy, 9. ↩

-

Ministry of Education, Singapore, Educational Policy, 5–9. ↩

-

Ministry of Education, Singapore, Educational Policy, 6. ↩

-

Ministry of Education, Singapore, Educational Policy, 2. ↩

-

Legislative Assembly, Singapore, White Paper on Education Policy, 4. ↩

-

Legislative Assembly, Singapore, White Paper on Education Policy, 7. ↩

-

Legislative Assembly, Singapore, White Paper on Education Policy, 10. ↩

-

Commission of Inquiry into Vocational and Technical Education in Singapore, Singapore, Report of the Commission, 61. ↩

-

Commission of Inquiry into Vocational and Technical Education in Singapore, Singapore, Report of the Commission, 38–46. ↩

-

Commission of Inquiry into Vocational and Technical Education in Singapore, Singapore, Report of the Commission, 60. ↩

-

Lim, Final Report, x. ↩

-

Lim, Final Report, 97. ↩

-

Goh and Education Study Team, Report on the Ministry of Education 1978, ii. ↩

-

See Appendix for a select list of educational policies and papers mentioned in this article. ↩