Undiscovered Spaces: An Interview With Boo Junfeng

Jennifer Lew interviews Sandcastles director Boo Junfeng about history, the National Library and the research process behind the making of his latest film.

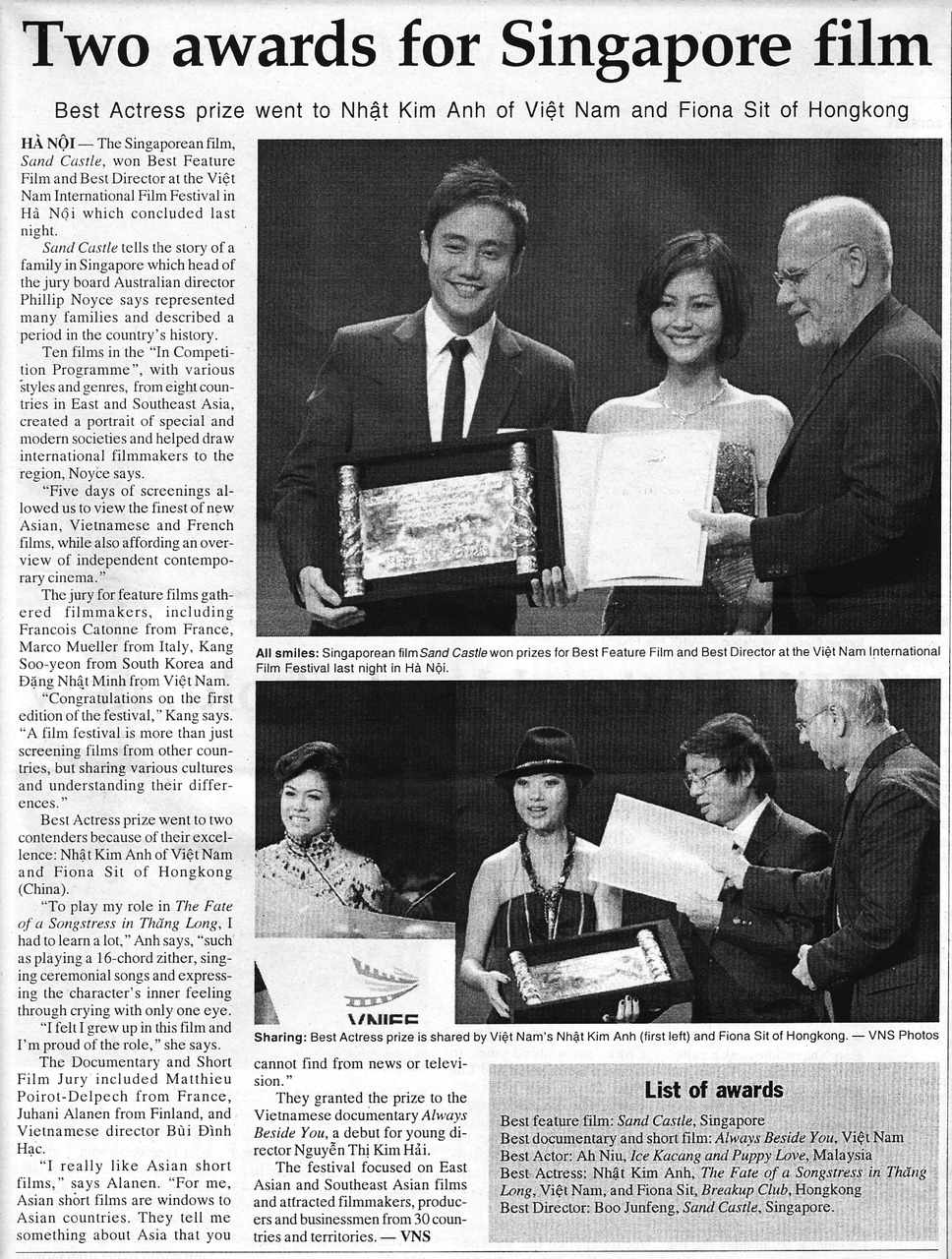

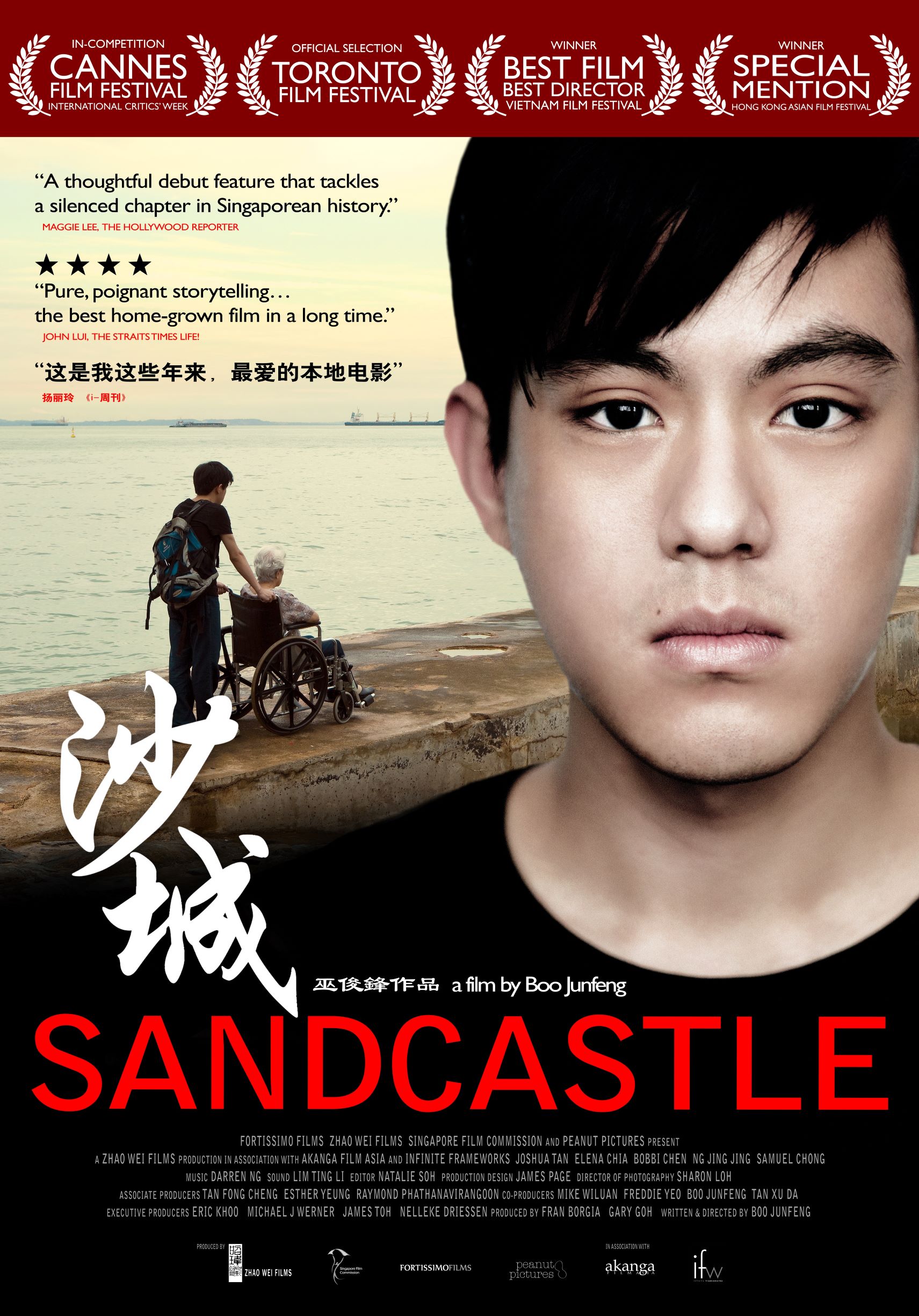

His debut feature film Sandcastle premiered at the Cannes Film Festival’s 49th International Critics’ Week – a first for Singapore cinema – and was the landslide winner of Best Feature Film, Best Director and the NETPAC Jury Prize at the inaugural Vietnam International Film Festival. The film was shown in Busan, London, Chicago, Vancouver, Toronto, Hong Kong and Paris at some of the world’s most prestigious international film festivals. A retrospective of his short film works resulted in five sold-out screenings at a commercial cineplex. And that is just what filmmaker Boo Junfeng has achieved last year alone.

On 26 August 2010, Sandcastle, his highly anticipated first feature opened in Singapore to a warm reception from public and critics alike. The subsequent media coverage dubbed Boo as the face of a new generation of auteurs, traced the swath he cut through the film festival circuit, and paused on occasion to muse on his rare sensitivity, prolific body of work in the short film medium, and his youth.

Lesser known, however, is the period of quiet study that marked the research that went into this history-rich cinematic work. We caught up with Boo during a brief window of time between festivals in Toronto and London, where we talked about history, the National Library and the research process behind the making of Sandcastle.

In your own words, tell us what Sandcastle is about.

Sandcastle is a coming-of-age story about a boy who witnesses his grandmother slipping into dementia and has to take care of her. At the same time, he discovers that his late father used to be a student activist in the 50s and 60s and that shakes his sense of identity. So [the character] starts to question his family background and who he is.

Tell us about the kind of research you did for Sandcastle.

I had three main sources for research: the National Library, the National Archives and some personal interviews that I came across. I realised that many of the facts were readily available, but I was more interested in testimonials that would give me a hint of the things that went through the minds of the students and activists of the past.

When I made cold calls to some of these former activists, they didn’t want to talk to me because they didn’t know who I was, and it was still a very sensitive subject for them. Eventually, I managed to speak with the son of a former leader and he told me what his childhood was like, what he had to go through, the people he got to know and things like that. That gave me an idea of what the activist community was like. Another former activist whom I spoke with said, “All I have to say about that period is already documented in Tangent, and you can find it in the library.”

So I went to look for it and I found a periodical with articles and interviews relating to issues that the Chinese-educated encountered, and what was great about this publication is that it was bilingual. It was written in Chinese but accompanied by an English translation. As someone who takes a whole week to read one article [in mandarin], it was very, very helpful. I understood a comprehensive interview in just a three-minute read, and I took away something insightful: how this activist felt about the past.

What was the difference between what you intended to study and what you discovered?

I had to understand where most academics are coming from and what kinds of views there are with regard to this subject. We understand the official narrative of history, but there is this alternative version that most of us don’t know of. So through some of this academic research I could see where the academic community and historians stand, and from there I found a perspective that reflected a wider spectrum of truth. Because the film is about questioning, and because it questions, it needs to offer these other various perspectives.

To probe further in that direction, would you say that in questioning history you are commemorating memory?

I think this show is about memory. There’s a reason why I parallel a woman’s involuntary loss of memory with her daughter-in-law’s voluntary loss of memory, and through these personal memories I present a larger collective memory and social memory. The film is about memory and how transient and mutable it can be.

Do you see your film as a documentation of memories, especially given the strong historical context that is quite specific to Singapore?

Sandcastle is a work of fiction, and what fiction can do is not simply document, but also evoke. If the film is successful, what I hope it evokes are these questions about memory and history. Through the story of one family’s memories and a boy’s desire to find out more about these histories and memories, we ourselves question this bigger idea of identity. We have been glorifying one side of the truth – what about the other side? It’s all about questions.

How did the National Library assist you in contextualising the historical element of the fictional works you create?

I really like working on Level 11 because of the amount of space that is there. I am someone who cannot be bound when I am thinking; I need to be in a big open space. So it was always a suitable environment for me to work in, especially when I was working on Tanjong Rhu [an earlier short film] and my accompanying thesis about the representation of gay characters in Singapore film. It so happened that the Singapore and Southeast Asian collections were on Level 11. I wrote much of the script for Sandcastle at Level 11, basing my research mainly on some of the publications in the Singapore and Southeast Asian collections, such as Tangent and The Scripting of a National History by Hong Lysa and Huang Jianli. These allowed me to understand the issues that the academic community and local historians have been writing and thinking about.

How do you think research as a whole contributes to the creative process, which is thought of as more intuitive, and how does it mesh together for you?

We may take creative licence when certain facts may not fit our creative agenda, but I always feel safer when I have enough knowledge of the subject matter. There are subjects that are quite close to my heart, and I still have to research on them to get a better understanding, and to be able to reflect on something that is larger than my own experiences. That is why research has always been very important to me. I’m also lucky to have friends who are just a phone call away, and they are very knowledgeable about a lot of these issues that I am interested in.

What is intuitive, eventually, is what I take away from all the information that I come across, and how I build characters, their lives, their relationships, the dynamics within these relationships and then the story flows from there. But the space in which this occurs has always been factual. After Sandcastle was released, it sparked a lot of interest from many people in the academic communities and amongst historians. This is the first time something like that is represented in a fictional film, and one of these interested parties happened to be Hong Lysa, whose book I read while working on the film.

Obviously, it is quite intimidating to meet and have a historian interview you about something you built based on your imagination of the past, but because of the research I had done, I was actually able to have a conversation with her. Much of this research lends to my credibility as a filmmaker and also to the credibility of the work, and gives it something to anchor itself onto, which is quite important.

Can libraries better serve the art or filmmaking community?

I have nothing to complain about since most of my needs for the purpose of research were met. It really is the researcher’s job [to seek resources]. I feel that what the library is doing is really good. I have friends from Korea who were very impressed that they could return a library book at any library across the island. I hope for Level 11 to be kept quiet and conducive. It will always be a place I know I can go to if I need that quiet space to think.

I think what the library provides is not only knowledge and information, but a space. Not everyone can have a quiet apartment with a beautiful view, so what a library provides is this space. This is why people were so attached to and emotional about the old Stamford library. Every city needs a library, because every city is noisy and distracting. The library is an oasis.

Research Associate

Government & Business Information Services

National Library