Popular Music in 1960s Singapore

Research Associate Joanna Tan traces the growth of English popular music in 1960s Singapore and the formation of local bands. She outlines the impact of nation-building on the music scene, and its eventual decline by the early 1970s.

From the late 1950s to the early 1970s, Singapore experienced a period of significant political and social change. The year 1959 marked the start of self-government for Singapore with the People’s Action Party forming the government. These political developments coincided with a flourishing English music scene that had developed with the introduction of popular music influences from abroad such as American rock ’n’ roll and British pop. This article traces the growth of English popular music in 1960s Singapore and the formation of local bands that became famous for their versions of British and American songs as well as original compositions that featured a unique blend of Western and Asian influences. The article also outlines the impact of nation-building on the music scene, and the eventual decline of the music scene by the early 1970s.

Influences from the West

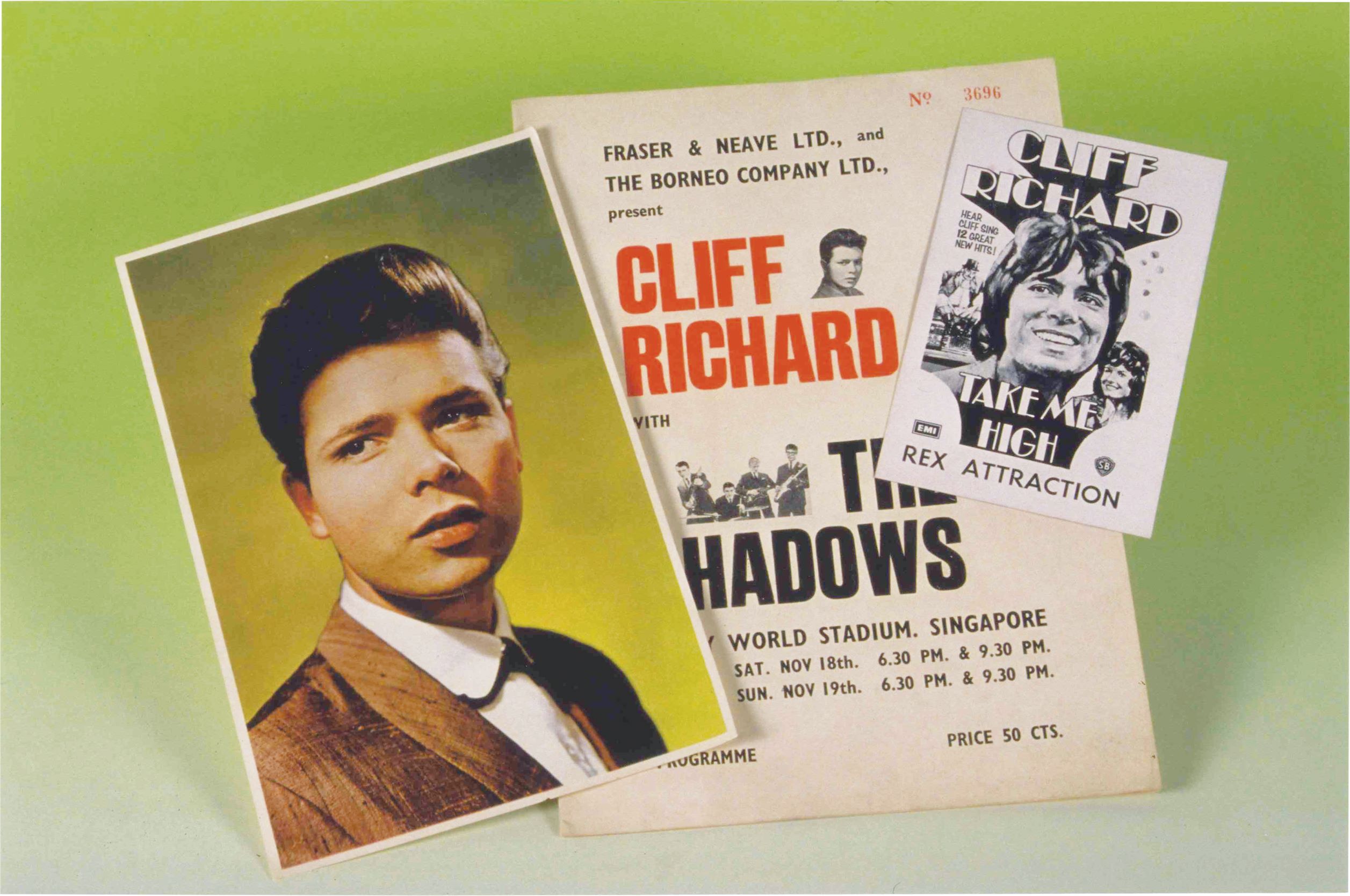

The early 1950s ushered in a marked change in the sound of English popular music. Les Paul invented the first solid-body electric guitar for the Gibson Guitar Company in 1952, while Leo Fender invented the Stratocaster guitar the following year. Both inventions produced the distinctive electric guitar sound that marked popular music in the decades that followed. In 1953, “Crazy Man Crazy” by Bill Haley became the first rock ‘n’ roll single to enter the Billboard charts, taking America by storm. Subsequent years saw the emergence of music stars like Chuck Berry, the Everly Brothers, Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly and Cliff Richard (who was seen as the British version of Presley).

Radio was crucial in introducing these new musical influences to Singapore. By the mid-1950s, Radio Malaya programmes such as Music of Les Paul, Radio Dance Club and Music Shop Review were bringing the sounds of jazz, swing and rhythm ’n’ blues from the USA to Singapore. The Rediffusion radio service began playing the occasional rock ’n’ roll single on its Platter Parade programme.1 However, it was only when Rock Around the Clock – the film featuring Bill Haley and the Comets’ signature tune of the same title – premiered at the Rex Theatre on 16 September 1956 that local audiences took notice. The film was enthusiastically received by an audience of 1,400, many of whom were British servicemen already familiar with the sounds of rock ’n’ roll.2

The year 1959 brought historic changes for Singapore. On 5 January, Radio Singapore replaced the Pan-Malayan Broadcasting Department. Several months later, the People’s Action Party (PAP) swept to power in the 30 May general election. Convinced that Singapore’s survival depended on Malaya, the new government began a push for Singapore to merge with Malaya.3 As part of the creation of a Malayan nation, the need to create a unified “Malayan culture” quickly became a priority for the new government.4 Believing that this nascent Malayan identity was threatened by degenerate cultural influences from the West, the government introduced prohibitions to eliminate agents of “yellow culture” (a term referring to delinquent and decadent behaviour commonly found in the West).5 Within barely a fortnight of the PAP’s electoral victory, Minister for Culture S. Rajaratnam announced that Radio Singapore programming would eschew rock ’n’ roll and sentimental music in favour of “serious programmes with a Malayan emphasis”.6 Jukeboxes, which city councillors had banned from coffeeshops were now banned island-wide, and pin-table saloons were outlawed soon after. The following year, the government ordered Rediffusion to stop broadcasting all rock ’n’ roll music.7

A Turning Point

Against this backdrop of official disapproval of popular forms of culture, Cliff Richard and The Shadows performed in Singapore in November 1961. Enthusiastic audiences of up to 20,000 turned up for the performances on 16, 19 and 20 November.

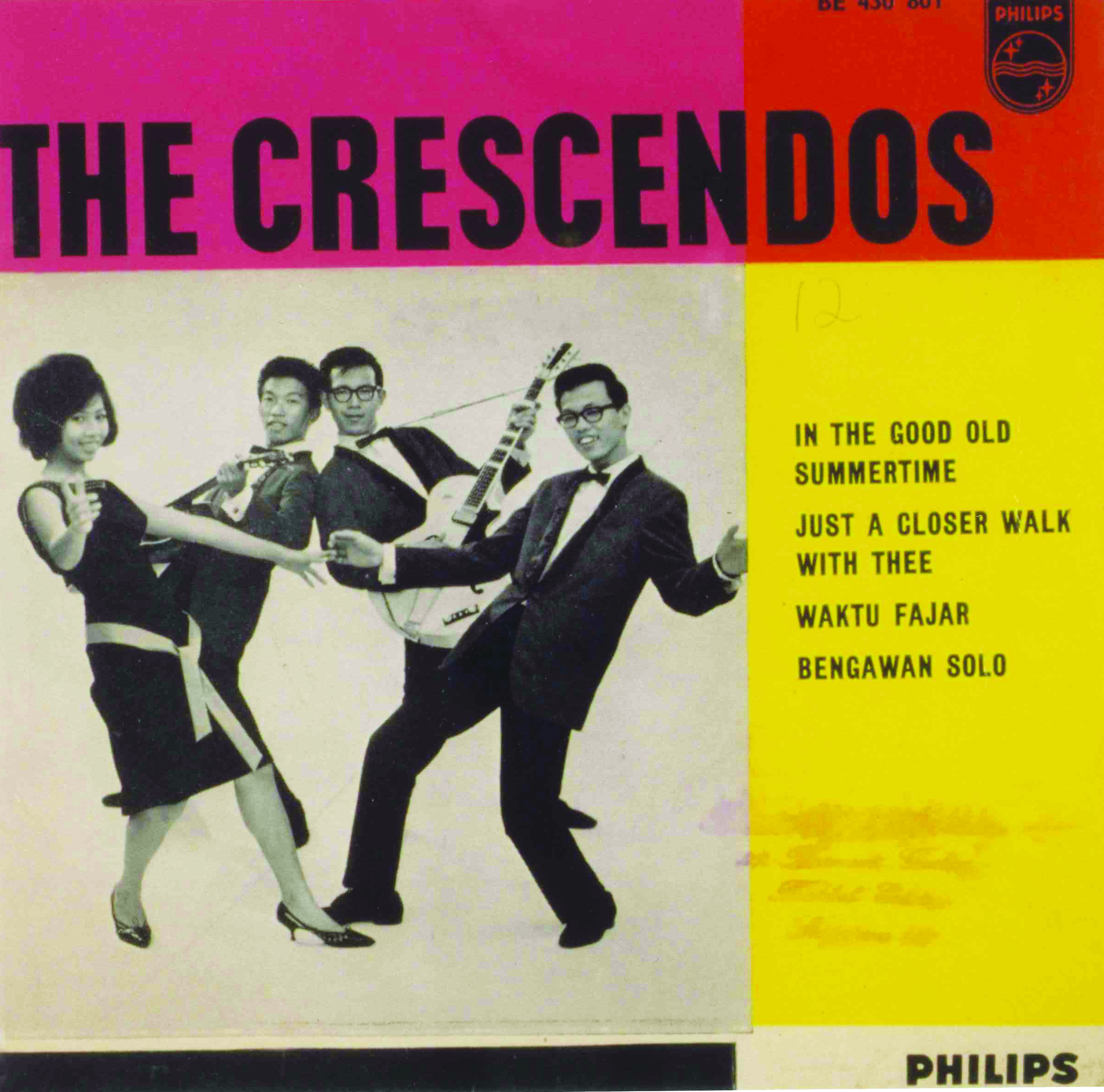

Prior to this, youth in Singapore had listened to British and American music only on the radio and on records. Watching their idols perform in person excited these young fans in a way that radio had been unable to do. Other foreign acts performed in Singapore in the 1960s, but the Cliff Richard performances were considered a turning point, spawning a host of imitators as these youths began forming bands in the early 1960s.8 As Reggie Verghese of The Quests (arguably the most successful Singapore band of that decade) put it, “I was hooked. All I wanted to do was play like them, and nothing was going to stop me from playing music.”9 One of the most striking traits of these new bands was the young age of their members, often of school-going age and still in their teens. Bands were usually formed by classmates or friends with musical interest or knowledge. Initially neighbours, the four members of The Quests were between 13 and 14 years of age when the band formed in 1961. Two of the members, Jap Chong and Raymond Leong, were schoolmates at Queenstown Secondary Technical School.10 Susan Lim was 14 years old and attending the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus when she began singing with The Crescendos in 1963. She was a friend of one of the band members’ sisters.11 Siva Choy, a pioneer blues musician, began performing with his brother James in 1957 when he was just 10 years old. They were performing as The Cyclones by the time Choy was 15.12 As Jerry Fernandez of The New Faces noted, “Bands came and went like moths. You [were] invited to join in a group by a classmate, friend or neighbour and you enjoyed the ride while it lasted.”13 Likewise, Vernon Cornelius, former frontman of The Trailers and The Quests, said, “We were all young and we had nothing to lose.”14

These bands formed on the basis of their mutual attraction to popular music rather than any notion of fame or fortune. The excitement of playing in a band was a reward in itself, even if they were not paid for the effort. Choy said, “We were given only $50 for transport, which we didn’t always receive, but we didn’t mind. Money didn’t matter then.”15 Henry Chua, bassist of The Quests, recalled the thrill of the band’s first paid gig: “We were rewarded with the princely sum of $20 to be shared among us. We felt rich. I never had more than 20 cents in my pocket in those lean days. That was the first time in my life that I really got paid for something I did.”16

Many aspiring musicians of that era did not have formal training in reading music or playing instruments; instead, they were self-taught and picked up music skills through trial and error, imitation, practice and experience. Chris Vadham of Western Union Band remembered learning to play the guitar from a music book.17 Henry Chua recalled the hours that band members spent listening to records, trying to work out the individual parts of songs. He had no musical training and learned his first two guitar chords from Jap Chong. Through regular practice, he taught himself to count bars, write chord charts and, eventually, to play the bass guitar.18

Initially unable to afford musical instruments and other equipment, these young musicians had to improvise. While practising for their first paid performance, The Quests created drumsticks from oversized pencils and a guitar from a biscuit tin strung with rubber bands.19 Equipment such as amplifiers was either homemade or borrowed. Siva Choy noted, “[In] those days, if you had a good amplifier, the chances of being asked to join a band were very good.”20

The frequent movement of members between bands meant that bands were occasionally short of someone to play a particular instrument. In keeping with the improvisational spirit of the time, many musicians were versatile and could play more than one instrument, which enabled band members to fill in for each other. When The Trailers thought to add a brass sound to their music in 1967, guitarists Victor Woo and Eric Tan did not have to spend much time learning to play the saxophone before introducing it in the song “Peter Gunn”, with Woo and Tan on saxophones while rhythm guitarist Edmund Tan filled in on the bass.21 Jerry Fernandez also recalled that members of The New Faces could “double up for one another… This versatility came in handy as it added to the quality of our show. We used to wow the audience when we suddenly switched from one instrument to the next”.22

Television and the Recording Industry

In 1963, The Beatles burst onto the music scene, marking the start of what was dubbed the British Invasion, and the phenomenon of fan hysteria known as Beatlemania. Television entered Singapore homes and from the start played a significant role in promoting local music talent. By 1966, Economic Development Board chairman Hon Sui Sen estimated that one in every six households in Singapore owned a television set.23 People also had access to televisions at community centres. Television programmes such as Pop Inn, which featured good local bands and singers as well as visiting acts, accelerated the popularity of these local bands. The Quests were one of the acts that appeared regularly on Pop Inn, which helped them to establish visibility in the public eye.

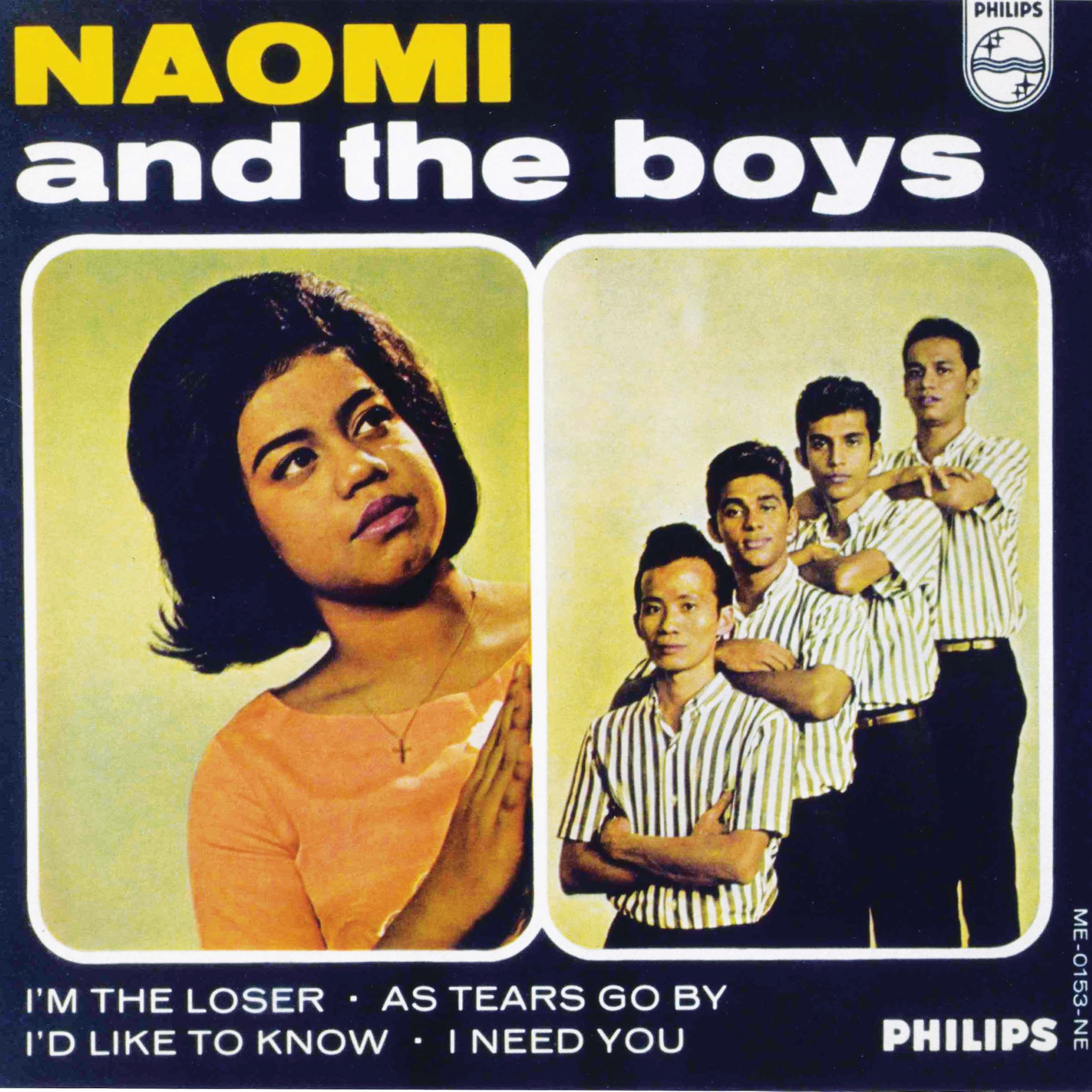

The recording industry in Singapore, which had been growing steadily for some years, registered significant growth during this period. A number of local bands signed contracts with recording companies and went on to release albums that did very well on the local music charts. While many albums contained cover versions of British and American songs, in some cases the covers outsold the originals by foreign acts. In 1961, Susan Lim and The Crescendos signed on with Philips International, becoming the first Singapore group to sign a contract with an international record label, paving the way for other local bands. They released their first single in 1963, a cover of “Mr Twister” that sold more than 10,000 copies on the local market, outstripping even the original version of the song by Connie Francis.24

Local bands, however, recognised that in order to differentiate themselves from foreign acts, they had to satisfy fans’ demands for the latest hit songs from abroad as well as come up with original material. In what seemed to be a triumph for the development of Malayan culture in Singapore, many albums containing original material were commercial successes, and it was not uncommon for albums to sell thousands of copies. The Crescendos’ 1963 release The Boy Next Door sold more than 10,000 copies, entered the Philips World Top Ten list, and is considered one of the band’s signature tunes.25 In 1964, Shanty, the song for which The Quests are still remembered, became the first song by a local band to top the Singapore charts, where it stayed for 12 weeks – displacing The Beatles who had been at No. 1.26 The Trailers replicated this feat in 1966 when their first single, “Do It Right”, knocked The Beatles off the top of the local charts, and spent seven weeks at No. 1. The song stayed on the charts for a record-breaking 14 consecutive weeks and sold 15,000 copies.27

A number of these songs were a unique blend of Western and Asian influences. While many bands sang in English, they also recorded songs in Mandarin or Malay and introduced Asian musical instruments in their song arrangements. Susan Lim and The Crescendos recorded Malay songs such as “Lenggang Kangkong” and “Waktu Fajar”, and the traditional Indonesian favourite “Bengawan Solo”. One of The Trailers’ biggest hits was “Phoenix Theme”, an instrumental rendition of a popular Chinese New Year tune, from their 1967 Chinese album that also included Taiwanese folk song “Alisan”.28

At the height of their popularity, and in the absence of appearances by bands from the West, local bands were in demand to perform at dance halls and private parties, on radio and television, and at large venues such as the Singapore Badminton Hall and the National Theatre. Due to the presence of British servicemen in Singapore, they were also asked to perform at military camps, mess halls and servicemen’s clubs. Nightclubs such as Golden Venus in Orchard Hotel began hiring well-known bands on contract because such resident bands were able to draw large crowds due to their fan base, especially on weekends.

These bands also became well known outside of Singapore and received invitations to perform abroad. Some went on tour to Malaysia, Thailand, Hong Kong and the Philippines. Hysterical fans greeted the bands, and their appearances in some places caused near riots. When The Quests toured East Malaysia in 1966, for instance, they were the biggest act to have appeared in that part of the country at the time and they received an overwhelming reception. The band was mobbed by fans, and during their performances, the music could barely be heard above the screams from the audience.29

The Decline of Popular Music

The close of the 1960s saw the decline of the local music scene for several reasons. Self-governance in 1959 eventually led to the phased withdrawal of British forces from Singapore, beginning in the late 1960s. With the decrease in British troops, there was a corresponding decline in demand for local bands to perform at British military bases.

In anticipation of the British withdrawal, the Singapore government began to pursue foreign investment and develop new industries in the early 1960s. The unexpected separation from Malaysia and independence in 1965 accelerated this political and socioeconomic transition. By the late 1960s, economic survival and the needs of the developing economy had become the imperatives that drove much of the government’s agenda, and citizens were called upon to support these national priorities through their contribution to economic growth. This drive to build a new economy extended to areas such as education. Education Minister Ong Pang Boon, for instance, urged parents to put their children into secondary education with a vocational emphasis in order to support Singapore’s drive to industrialise by creating skilled workers.30

The creation of a new economy was accompanied by the moulding of a new society. While anti-yellow culture measures in the early 1960s had reduced external influences and enabled the number of bands producing original music with local influences to grow, the anti-yellow campaign began to have a negative impact by the late 1960s. The government regarded local music as being heavily influenced by the West and, by this time, associated it with a culture of drug use and disorderliness. Men were banned from sporting long hair, and police patrols scoured clubs on Orchard Road, issuing warnings to musicians whose hair was considered too long. The ruling also applied to foreign acts performing in Singapore: Cliff Richard, slated to perform in Singapore in 1972, refused to cut his hair and was therefore not allowed to enter the country. In 1973, the government closed down six discos, including popular ones such as the Boiler Room, Pink Pussycat and Barbarella, and instituted restrictions on all remaining discos. These included a ban on alcohol and the denial of entry to men with long hair.31

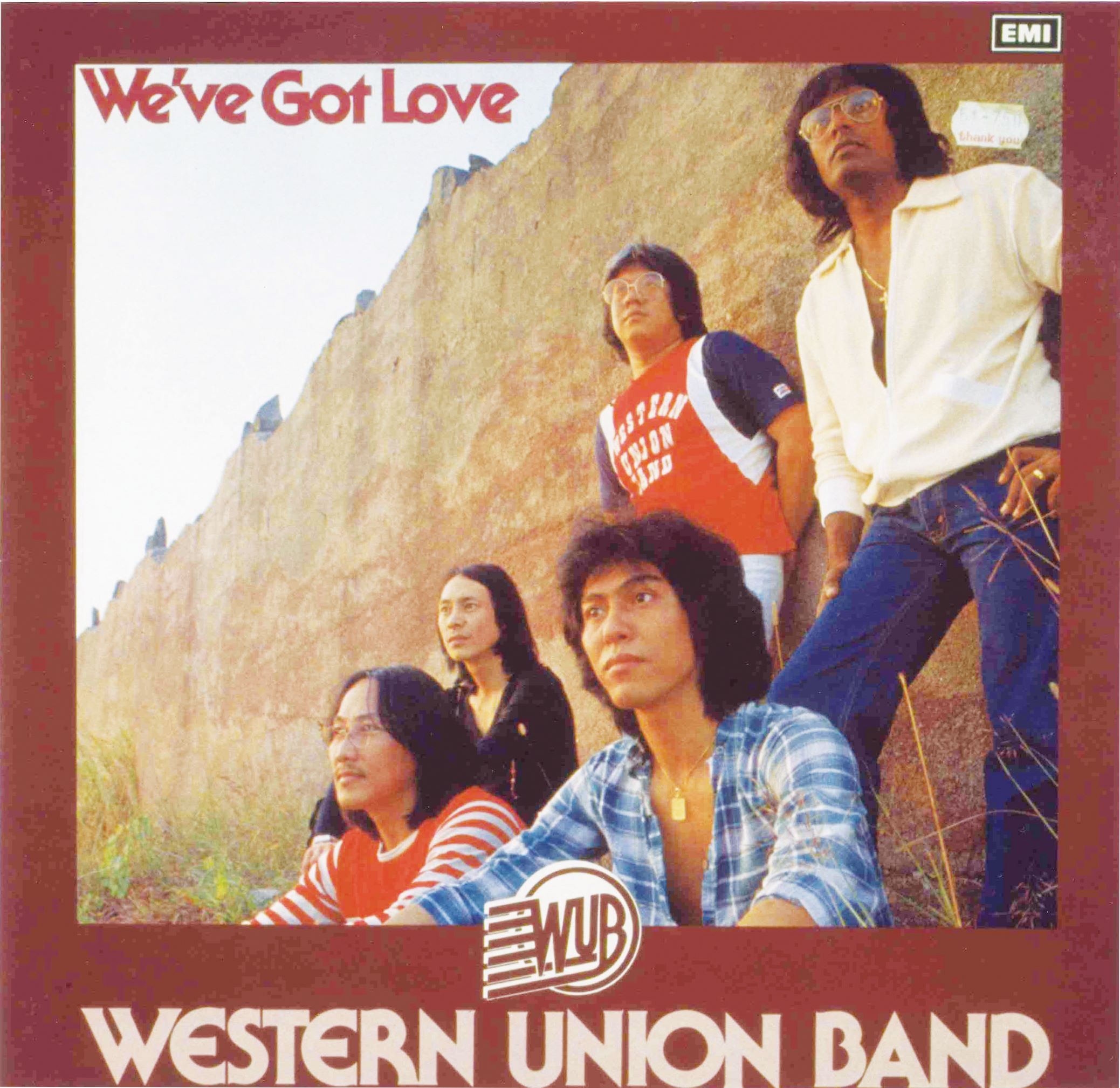

In this new era of industrialisation, musicians who had established successful bands in their teens were also reaching a new stage in life. They had spent much of the 1960s juggling school and music and then work and music, but they were now in their 20s and in search of a more stable and financially secure future. With the dwindling of expatriate audiences who had made the music scene economically viable as well as the rising number of social restrictions and the pressure to be useful members of society, these young musicians found themselves at a crossroads. They began to regard their situation as increasingly untenable, and most eventually bowed to the pressure. Henry Chua documents The Quests’ fatigue by the late 1960s, and the feeling that they had reached a pinnacle where there was nothing more to be achieved.32 At the same time, he was concerned about the long-term prospects of a musician’s life and chose to leave the band in 1967 to pursue an engineering career. Reggie Verghese, for his part, “knew that music alone wasn’t enough… I had a fear that it wasn’t going to last”.33 Victor Woo of The Trailers completed his computer science examinations in 1967 and later became a company executive, leaving the band in 1970. The Trailers gave up recording albums by 1972 and were defunct by the mid-1970s.34 The early 1970s saw the disbanding of other groups such as the Bee Jays, Mandarins, Flybaits and Fried Ice.35

Some of these pioneers of Singapore popular music continued to make their livelihoods in the music industry. Other 1960s musicians took up day jobs outside the industry and stayed in touch with music by taking on alternate night jobs playing music in hotel lounges and bars. Some even attempted a comeback. Vernon Cornelius, one-time frontman of The Quests, Eric Tan, former bassist of The Trailers, and several other musicians formed The Overheads in 1989 and released an album that gained modest but short-lived success.

Unlike these stalwarts, however, most other musicians simply grew older, lost touch with music and faded into history. While it is difficult to say whether the once-lively music industry would have been sustainable beyond the 1960s, it is certainly true that since then, local musicians have found it difficult to achieve the same level of popularity, support and commercial success that came so readily during those golden years.

The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Dr Mark Emmanuel, Department of History, National University of Singapore in reviewing this article.

Research Associate

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library

REFERENCES

Burhanudin Buang. (2001). Pop Yeh Yeh music in Singapore, 1963–1971. Singapore: National University of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 781.629928095957 BUR)

Cheong, V. (2008). Singapore 60’s pop music hall of fame. Retrieved from mocamborainbow.blogspot.com website.

Chua, H. (2001). Call it Shanty: The story of The Quests. Singapore: BigO Books. (Call no.: RSING 781.66 CHU)

Conceicao, R. (2009). To be rock but not to roll: A 40-year odyssey (1966–2006) of a Singapore pop musician, Jerry Fernandez. Singapore: Comdesign Associates. (Call no.: RSING 781.64092 CON)

Kong, L. (1999). The invention of heritage: Popular music in Singapore. Asian Studies Review, 23 (1), 1–25.

Lent, J.A. (Ed.). (1995). Asian popular culture. Boulder: Westview Press. (Call no.: RSING 306.095 ASI)

Lockard, C.A. (1998). Dance of life: Popular music and politics in Southeast Asia. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. (Call no.: RSING 306.484 LOC)

Pereira, J.C. (1999). Legends of the golden venus. Singapore: Times Editions. (Call no.: RSING q781.64095957 PER)

Pereira, J.C. (2005). Obscured music: The trailers. Fancy magazine. Retrieved from Fancymag.com website.

NOTES

-

Today’s radio programme for Singapore. (1957, July 29). The Singapore Free Press, p. 7; Rock ‘n roll – this is it! (1956, September 13). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Swing-and-sway rhythm starts early-morning jive session. (1956, September 17). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Turnbull, C.M. (2009). A history of modern Singapore, 1819–2005 (pp. 266, 274–277). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TUR); One Malayan nation – the No. 1 task of the Government. (1959, July 22). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lee: We’ll breed new strain of culture. (1959, August 3). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The term “yellow culture” is a transition of the Chinese term used to describe the decadent behaviour found in 19th-century China, such as corruption, opium-smoking, gambling and prostitution, which were seen as contributing to the fall of the Middle Kingdom. ↩

-

Radio: The new order. (1959, June 10). The Straits Times, p. 9; Radio Singapore to be serious but not dull. (1959, June 17). The Singapore Free Press, p. 7; The rock music goes off the air. (1959, June 17). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 10 Jun 1959, p. 9; ‘Juke box ban is too drastic’. (1957, May 8). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5; Peril of pin-table culture – by Home Minister. (1959, June 25). The Straits Times, p. 1; Rediffusion told us to stop all rock ‘n roll music. (1960, March 19). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chandran, K. (1986, March 14). Those were the days…. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chua, H. (2001). Call it Shanty: The story of The Quests (p. 167). Singapore: BigO Books. (Call no.: RSING 781.66 CHU) ↩

-

Jap Chong, Raymond Leong, Henry Chua and Lim Wee Guan were neighbours living in Tiong Bahru. The name of the band was derived from the school magazine of Queenstown Secondary Technical School (now Queenstown Secondary School). ↩

-

Hammonds, K. (1963, March 3). Spinning with cutie Susan. The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Pereira, J.C. (1999). Legends of the Golden Venus (pp. 11–25). Singapore: Times Editions. (Call no.: RSING q781.64095957 PER) ↩

-

Conceicao, R. (2009). To be rock but not to roll: A 40-year odyssey (1966–2006) of a Singapore pop musician, Jerry Fernandez (pp. 4–5). Singapore: Comdesign Associates. (Call no.: RSING 781.64092 CON) ↩

-

1965: Those were the days. (1990, July 6). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

For love of the sixties. (1982, April 15). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

For the actual performance for a Christmas party at the St Andrew’s Mission Hospital on 25 December 1961, the band played using guitars borrowed from friends and a drum set that once belonged to Raymond Leong’s uncle. (Chua, 2001, pp. 19, 31–32) ↩

-

Pereira, J.C. (2005). Obscured music: The trailers. Fancy magazine. Retrieved from Fancymag.com website. ↩

-

One home in six has TV. (1966, April 28). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Crescendos find a place in top ten. (1963, September 30). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 30 Sep 1963, p. 5. ↩

-

The Quests beat Beatles to reach top of Hit Parade. (1964, November 20). The Straits Times, p. 4; What’s new? Seven pussycats who’ve clawed their way to stardom. (1967, May 21). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 21 May 1967, p. 11. ↩

-

Pereira, 2005. ↩

-

S’pore races against time to raise new industries. (1963, January 3). The Straits Times, p. 16; Pioneers spirit needed anew, says Lim. (1965, December 14). The Straits Times, p. 10; Vocational education important for S’pore, says Ong. (1967, July 6). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

De Silva, G. (1972, June 28). Hair-cut for local musicians on police advice. The Straits Times, p. 8; De Silva, G. (1972, August 22). Cliff kept his locks, but EMI lost $10,000. The Straits Times, p. 15; Chandran, R., & Pereira, G. (1973, November 2). Govt shuts down 6 discos. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Pereira, 2005. ↩

-

Low, J. (1970, October 24). POP goes the band but the beat goes on. The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩