In the Family: Family History Resources in the National Library

Tracing our family history can be a slow and laborious process. The National Library has various resources to help the researcher complete the journey of discovering one’s roots.

Grandfathers’ Stories

The best place to begin exploring one’s family history is one’s own family, both immediate and extended. Talking to elderly relatives is an intimate process that reveals lost names, fleshes out characters and unravels hidden stories. It is not always easy to interview those who are most familiar to us. Techniques in interviewing relatives and fishing for treasured nuggets in family histories are explained in publications such as Verde’s Touching Tomorrow (2000), which sees the process of the oral interview as a gift for the whole family. As families share, they invariably uncover photographs, memorabilia and letters. These become touchstones, triggering memories in others or carrying new information, often of a more personal nature.

Keeping familial records, photographs and ephemera organised is just as important as developing a strategy for research. The process is often tedious and an art in itself. One useful guide for newcomers is Taylor’s Preserving Your Family (2001), which outlines in detail the process of restoring and organising old photographs.

Chatting with aged relatives, leafing through old letters and documents, analysing photographs and examining family heirlooms can open doors to hidden branches of one’s family tree.

Beginning with the End

A name with a birth or death date is the first step in fleshing out details of a member in the family tree.1 Sometimes starting with the end may prove more profitable than trying to trace the beginning. Often a deceased who has just passed away is still remembered by surviving family members who can recall events and details associated with the individual. A simple obituary in the newspaper or community newsletter can reveal a slew of other names and relationships, of sons and daughters, grandsons and nephews. More established patriarchs (or matriarchs) may have eulogies published.

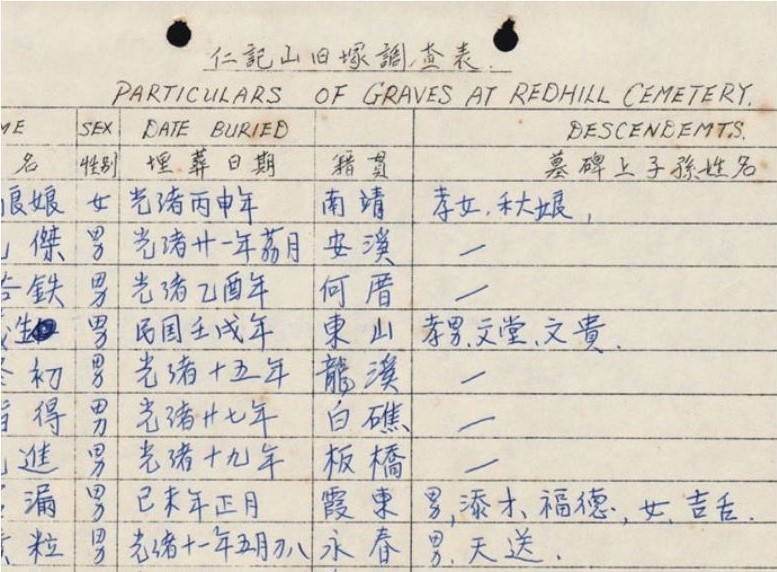

Persistence and creativity are important keys for dredging up information of our ancestors. Vernacular names are often mispronounced and their spellings confused. Even with a searchable database, variant names, acronyms and spellings should be attempted before giving up the search. Etchings of names on headstones are important clues that can move the research forward. Birth dates, places of birth, aliases or commendations are often gleaned from gravestones. There are publications that have transcribed details of the tombstones of the early colonialists.2 Burial registers and exhumation records are also invaluable sources of information. Donated by Kuan Swee Huat, the Hokkien Huay Kuan Exhumation Records, spanning 1948–1951 and 1936–1965, list some 10,000 Chinese graves exhumed from Redhill in the 1960s. They carry information such as the date of exhumation and burial, name, sex and dialect group of the deceased as well as names of their descendants.

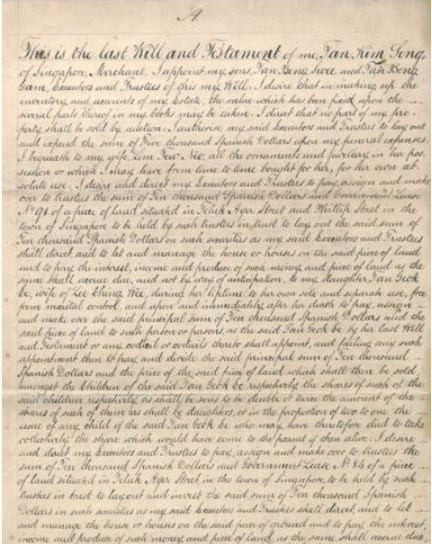

Legal papers such as petitions, writs of summons, power of attorney, property ownership, wills and testaments such as those in the collections of Koh Seow Chuan,3 can throw much light on a family’s genealogy. The handwritten will and testament of well-known philanthropist Tan Kim Seng dated 1862, for example, revealed not only the wealth of the deceased, but also his descendants and beneficiaries, many of whom were well-known in their own capacity.

The Straits Times and The Singapore Free Press are fully searchable on NewspaperSG, an online archive of Singapore news. Dating back to the mid-19th century, these newspapers carry announcements of births, marriages and deaths, with more details for well-known people. Passenger lists are also published sometimes, giving information on a person’s destination, place of embarkation and the ship’s name. Another useful source of information comes from notices of exhumation published in these dailies. Non-English-language newspapers such as Berita Harian, Nanyang Siang Pau, Sin Chew Jit Poh and Tamil Murasu are also available through this portal, although they were published much later and may have less to offer. Available on microfilm are other dailies such as the Malaya Tribune, the Singapore Herald and the Singapore Standard which are alternative sources of news.

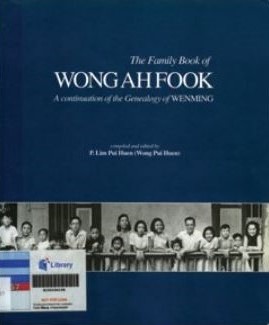

Whole donations of records, photographs and books with connections to well-known families such as the Wong Ah Fook Collection, the Wang Tso and Hsiu Chin Collection and the Wu Lien-Teh Collection are also gems to family historians of these pedigree families. The collection of Wong Ah Fook (1837–1918) donated by his great-granddaughter Datin Patricia Lim includes genealogies, wills, archival records, photographs, account books, press cuttings, maps and publications related to the family’s history. Mr Wang Tso and his wife Madam Chen Hsiu Chin were prominent members in the educational field in the 1950s to 1960s, particularly of Chinese institutions such as the Pay Fong High School, the Yock Eng High School and the Nanyang University. Their collection, donated by their daughter Mrs Lee-Wang Cheng Yeng, has over 2,000 documents, comprising mainly letters and personal documents of Mr and Mrs Wang. The recently donated collection of Wu Lien-Teh, a renowned physician in both Malaya and China, has unique photographs and original works by both Wu and his first wife, Ruth.4

The jiapu5 (家谱) is a clan’s history or lineage, recording important aspects such as the origin of the family name, the locality of the ancestry, the clan’s migration history, birth and marriage records, honours and achievements. The jiapu is the window to the family tree and its branches in Chinese families. One can search the jiapus available at the National Library or call the respective huiguan (会馆), or clan associations, to check on their genealogical records.

A Life Worked Out

Another approach to family history research is through a person’s profession, career or trade. The Buku Merah or Straits Times directory is a key reference for deriving details of business leaders and was an early “who’s who” list in Singapore. The earliest extant print of the directory in the library dates back to 1846.6 Besides a list of residents with their full names, professional titles and addresses, the publication also identifies companies by trade and industry and the heads of these entities.

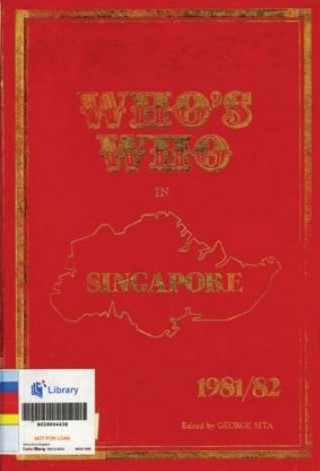

There are several Who’s Who listings for Malaya and Singapore which range from as early as 1918 to the present day, giving details of Singapore’s and Malaya’s elite such as birth dates, positions held, accomplishments and places of residence. The later Who’s Who extends beyond business and community leaders to include civil servants and industry leaders. The 1948 directory of Who’s Who by Menon gives an alphabetical list of names, with place of origin, education, positions held before the war, social and community work and even recreational interests and hobbies. Photographs in black and white accompany some profiles. The Who’s Who of Singapore and Malaysia of the 1970s and the 1980s include a list of lecturers in tertiary institutions and private doctors besides civil servants, merchants, managers and royalty.

Life in the Community

The middle class was privileged with time and money and often joined clubs, societies, hobby groups and communities. Newsletters and commemoratives from these organisations sometimes carry reports of individual contributions. The 90th anniversary commemorative of the scouts7 in Singapore is an example of a community publication which profiles key contributors. Some social clubs such as the Singapore Cricket Club (1852), the Swiss Club (1871), the Singapore Recreation Club (1883), and the Singapore Island Country Club (1891) date back to the 19th century. Unfortunately, although these early club commemoratives provide useful information on the happenings and people in their organisations, newsletters and magazines from the 19th century are scant. Nevertheless, looking up articles produced by these clubs or referring to their older members may prove useful as in the examples of the Peranakan Association and the Association of British Malaya.

Although our ancestors often came with little but the clothes on their backs, some succeeded through sheer perseverance and good luck. A number gave their wealth and time back to community and religious institutions. The philanthropist who donated generously to community causes would have his name engraved on temple steeles or remembered in clan association records. The bibliography on the publications of the Singapore Chinese Clan Associations8 references holdings on clan associations that are in the National Library, the National Archives, the Nanyang Technological University, the National University of Singapore, among other institutions. Churches also published newsletters on the contributions of ordinary people. They include the Methodist Message,9 St Andrew’s Outlook10 and the Diocesan Digest.11

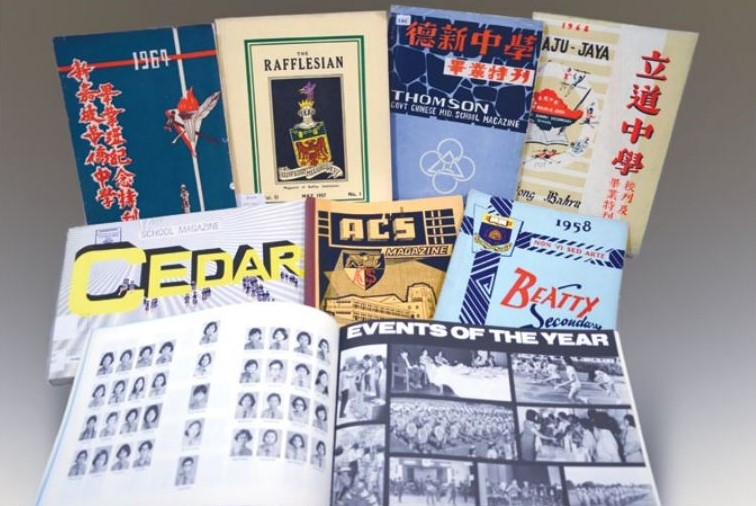

School records are another rich resource. These include school magazines, commemorative and souvenir publications. Besides class photographs of teachers and students, these publications also highlight the academic, sporting and leadership accomplishments of their students. The National Library has school magazines mainly from the 1960s onwards, an example of which is the Cedar Magazine. A school with a long history like the Raffles Institution, has magazines dating back to the 1880s.12 Many established schools also have their own archives or may even have uploaded some school records and photographs online. Schools affiliated with religious groups such as churches, temples and mosques often have descriptive accounts of school events and their participants in their respective religious publications.

Gateway to Genealogy Research

The National Library has several reference publications that provide pointers on resources and approaches to constructing family trees. For instance, Foy’s Family History for Beginners (2011) gives concrete yet simple steps to genealogical research, while Smolenyak’s Who Do You Think You Are? (2009) shows examples of actual family trees and how to go about piecing one. Skulnick and Moorhead’s 500 Brickwall Solutions to Genealogy Problems (2003) along with its sister edition More Brickwall Solutions to Genealogy Problems (2004), written for family historians who face brickwalls in their research, offers strategies on overcoming dead ends. For a local perspective, the National Library has its own compilations and guides of materials in its holdings, ranging from the introductory resource guide entitled Tracing Your Family History (2003), which gives a good survey of key resources, to the more extensive Sources on Family History (2008) by Kartini Saparudin, which covers resource materials by genre and by key racial groups. Ng Hui Ling has also compiled an extensive library guide on Chinese genealogy research.13

The internet can be a bountiful resource for the family historian. Books such as Marelli’s @ Home With Your ancestors.com (2007) and Family History on the Net (2007) offer useful genealogy-related links and websites.

A popular first-stop for genealogy research on the web is FamilySearch,14 one of the largest genealogy services in the world, with millions of family history records available free online. FamilySearch is a service provided by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. They also run over 4,500 family history centres in 70 countries including a chapter on Singapore, which may be worth a visit. Unfortunately much of the rich family history found on the net is mainly for non-Asians. However, there are some websites that serve the local community. One such site is the portal of the National Archives of Singapore at https://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/. It is a gateway to the records, photographs, maps and private collections of the archives in Singapore. To get the most out of its extensive records, a visit to the National Archives is a definite must as a number of its records are not available online in full-text. Another key organisation is the newly formed Genealogy Society Singapore,15 which has helped a number of Singaporeans to trace their roots all the way back to Xiamen and Hainan.

Ghosts in the Attic

Every family has skeletons and secrets – an illegitimate son, an adopted child, a criminal record, poverty or insanity. Yet these members may prove most vital to the building of one’s family tree. It is from these family members that records may be uncovered as documentation is often required for cases of adoption and insanity, or appeals for financial support.

Each family has tales of bravado, tragedy and bliss waiting to be shared and retold. There are publications that guide researchers on publishing their family stories. They include Titford’s Writing Up Your Family History (2003) and Carmack’s You Can Write Your Family History (2003).

Published family histories are the nuts and bolts of genealogical research. Particularly useful for their insights into Malayan families are family histories such as Lim’s Myth and Reality (1988) and Ong’s Chew Boon Lay (2002), which includes four charts on their extensive family tree. The Shepherdson family made headlines when they published their genealogy Journey to the Straits (2003) which spanned three centuries from their earliest-known ancestor who travelled beyond the British shores to Southeast Asia. They were even featured in an exhibition on family history research at the National Library. The family followed up with another book The Great Genealogical Search (2010), which records their research experience from traditional repositories such as archives and libraries as well as modern tools, in particular, the internet and DNA matching. A member of the Shepherdson family also published her personal adventure of tracing one’s family in Looking Back (2006). These three publications demonstrate the various approaches of tracing one’s family history, proven techniques and experiences, and how the interplay of memories and records reconstructed the lives of people.

The Shepherdson story is an example of family history coming full circle, where the research bore fruit in the form of more books and records to serve other family historians. Although the process of researching and documenting a family tree may seem never-ending, one can be encouraged by fellow sojourners and those who have found their roots through the resources at the National Library.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Mr Lai Yeen Pong, Consultant, National Library Board, and Miss Alicia Yeo, Manager, National Library Group, in reviewing this paper.

Bonny Tan is a Senior Librarian with the National Library Heritage division. She is the compiler of A Baba Bibliography (2007) and An Orientalist’s Treasure Trove of Malaya and Beyond: Catalogue of Gibson-Hill Collection at the National Library Singapore (2008) and is a regular contributor to BiblioAsia and Singapore Infopedia, the National Library Board’s online encyclopedia on Singapore.

Bonny Tan is a Senior Librarian with the National Library Heritage division. She is the compiler of A Baba Bibliography (2007) and An Orientalist’s Treasure Trove of Malaya and Beyond: Catalogue of Gibson-Hill Collection at the National Library Singapore (2008) and is a regular contributor to BiblioAsia and Singapore Infopedia, the National Library Board’s online encyclopedia on Singapore.REFERENCES

福建会馆. (1948). 福建会馆磷记山, 老山, 羔丕山地租部, 民国三十七年四月份立. 未出版手稿. (Call no.: Chinese RRARE 333.5095957 FJH; Microfilm no.: NL30213)

黄美萍, 钟伟耀 & 林永美 (编者). (2007). 新加坡宗乡会馆出版书刊目录 = A bibliography on the publications of Singapore Chinese Clan Associations. 新加坡: 新加坡国家图书馆管理局. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 016.95957 BIB)

新加坡福建会馆 . (1963). 新加坡福建会馆仁记山逐日迁冢纪录底, 自一九六三年五月十八日起至[一九六三年六月十七日], No. 4230__至__8250. 未出版手稿. (Call no.: Chinese RRARE 929.5095957 XJP; Microfilm no.: NL30216)

新加坡福建会馆. (1965). 新加坡福建会馆磷记山逐日迁冢纪录底, 自一九六三年七月十九日至[一九六五年三月十三日], No. 12251 to [16915]. 未出版手稿. (Call no.: Chinese RRARE 929.5095957 XJP; Microfilm no.: NL30217)

500 brickwall solutions to genealogy problems. (2003). Toronto: Moorshead Magazines.

Carmack, S.D. (2003). You can write your family history. Cincinnati, Ohio: Betterway Books.

Chew, K.C., & Chew, E. (Eds.). (2002). Chew Boon Lay: A family traces its history: A family album. Singapore: Ong Chwee Im. (Call no.: RSING 929.2095957 CHE)

Church of England, Diocese of Singapore. (194–). Diocesan digest: The Diocese of Singapore. Singapore: Church of England, Diocese of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING

283.5957 DD)

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. (2012). FamilySearch. Retrieved from Family Search website.

Family history on the net. (2007). Newbury: Countryside Books.

Foy, K. (2011). Family history for beginners. Stroud, Gloucester: History Press. (Call no.: R 929.1072 FOY)

Genealogy Society of Singapore. (2012). Genealogy Society Singapore. Retrieved from Singapore Genealogy website.

Hameedah, M.I., & Ong, E.C. (2003). Tracing your family history. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. (This article cannot be found)

Harfield, A.G. (1979). Fort Canning Cemetery, Singapore. [s.i.: s.n.]. (Call no.: RCLOS 929.5095957 HAR)

Harfield, A.G. (1988). Early cemeteries in Singapore. London: British Association for Cemeteries in South Asia. (Call no.: RSING 929.5095957 HAR)

Lim, P.H.P. (1998). Myth and reality: Researching the Huang genealogies. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 928.108995105957 LIM)

Lim, P.H.P. (2005). The family book of Wong Ah Fook: A continuation of the genealogy of Wenming. Singapore: [P. Lim P.H. & Lim S.G.]. (Call no.: RSING 929.2095957 FAM)

Marelli, D. (2007). @ home with your ancestors.com: How to research family history using the internet. Oxford: How To Books.

Methodist Church. (1952–). The Methodist message. Singapore: Methodist Church. (Call no.: RSING 287.05 MM)

National Archives of Singapore. (2005). Retrieved from https://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/

Ng, H.L. (2011). Genealogy research resources. Retrieved from Libguides website.

Ong, C.I. (2006). The journey from White Rock: The Ong Chong Chew family tree. Singapore: Ong Chew Im. (Call no.: RSING 929.2095957 ONG)

Presbyterian Church in Malaya. (1912–). Saint Andrew’s outlook: Annual record of the Presbyterian Church in Malaya, Sumatra, Burma and Siam. Singapore: Presbyterian Church in Malaya. Available via PublicationSG.

Saparudin, K. (2008). Sources on family history: A select bibliography. Singapore: National Library Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 016.9292095957 LEE)

Saparudin, K. et al. (2008). Sources on family history: A select bibliography. Singapore: National Library Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 016.9292095957 LEE)

Schweizer-Iten, H. (1981). One hundred years of the Swiss Club and the Swiss community in Singapore, 1871–1971. Singapore: The Swiss Club. (Call no.: RSING 367.95957 SCH)

Scully-Shepherdson, M. (2006). Looking back: A family history discovered and remembered. Singapore: Martha Scully-Shepherdson. (Call no.: RSING 929.2095957 SCU)

Shepherdson, K.L., & Shepherdson, P.J. (2003). Journey to the Straits: The Shepherdson story. Singapore: Shepherdson Family. Singapore: Shepherdson Family. (Call no.: RSING 929.2095957 SHE)

Shepherdson, K.L., Shepherdson, P.J., & D’Almeida, K. (2010). The great genealogical search: A remarkable story of how one family traced its roots in the East Indies and discovered its British ancestry. Singapore: Straits Consultancy & Pub. (Call no.: RSING 929.107205957 SHE)

Skulnick, M., & Moorshead, V. (Eds.). (2004). More brickwall solutions to genealogy problems. Toronto: Family Chronicle Magazine. (Call no.: R 929.1072 MOR)

Smolenyak, M. (2009). Who do you think you are? The essential guide to tracing your family history. New York: Viking.

Stallwood, H.Q. (1912, June). The old cemetery on Fort Canning, Singapore: With a plan and four plates. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 61, 77–126. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Tan, K. (2002). Scouting in Singapore 1920–2000. Singapore: Singapore Scout Association and National Archives of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 369.43095957 TAN)

Taylor, M.A. (2001). Preserving your family photographs: How to organize, present, and restore your precious family images. Cincinnati, O.H.: Betterway Books. (Not available in NLB holdings)

The Peranakan Association newsletter (1995–). Singapore: The Peranakan Association. (Call no.: RSING 305.895105957 PAN)

Titford, J. (2003). Writing up your family history: A do-it yourself guide. Newbury, Berkshire: Countryside Books. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Verde, M.L. (2000). Touching tomorrow: How to interview your loved ones to capture a lifetime of memories on video or audio. New York: Fireside. (Call no.: RCLOS 929.1 LOV)

Walter, C. (2007). Family history on the net. Newbury: Countryside Books. (Call no.: R 929.102854678 FHON)

Who’s who in Singapore 1981/82. (1982). Singapore: City Who’s Who. (Call no.: RSING 920.05057 WWA)

NOTES

-

Primary sources, particularly birth, marriage and death certificates, provide links to the family tree. These records can be obtained from the Immigration and Checkpoints Authority, the Registry of Marriages and the National Archives of Singapore. The public can apply for a birth and death extract from eXtracts Online at Government websites. ↩

-

They include Harfield, A.G. (1979). Fort Canning Cemetery, Singapore. [s.i.: s.n.]. (Call no.: RCLOS 929.5095957 HAR), along with Stallwood, H.Q. (1912, June). The old cemetery on Fort Canning, Singapore: With a plan and four plates. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 61, 77–126. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Koh Seow Chuan, a retired architect and founder of DP Architects, donated his rich collection of documents and records to the National Library Board. ↩

-

The March 2012 issue of BiblioAsia has a profile of Wu Lien-Teh and highlights of his collection. Wee, T. B. (2012, March). A life less ordinary: Wu Lien-Teh the plague fighter. BiblioAsia, 7 (4), 34–37. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Zupu (族谱) and zongpu (宗璞) are terms that are used interchangeably with jiapu. ↩

-

Singapore almanac and directory. (1846–1869). Singapore: Straits Times Press. (Call no.: RRARE 382.09595 STR; Microfilm nos.: NL2363, NL2362) ↩

-

Tan’s Scouting in Singapore 1920–2000. Tan, K.Y.L., & Wan, M.H. (2002). Scouting in Singapore 1920–2000. Singapore: Singapore Scout Association and National Archives of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 369.43095957 TAN) ↩

-

The Singapore Chinese Clan Associations resource guide is from Libguides website. ↩

-

For example, the Methodist Message, previously titled the Malayan Message, gives interesting accounts of individuals and their accomplishments, positions held, church contributions made and sometimes even a profile. ↩

-

This is the annual newsletter of the Presbyterian Church in Southeast Asia dating from 1912. ↩

-

A newsletter of the Anglican Church in Singapore that began at the turn of the 20th century. ↩

-

The library has copies of The Rafflesian from 1887 and of St Andrew’s School Up and On from 1928 onwards. All early versions are accessible through microfilm. The centenary and souvenir publications of these schools also provide rich details. These are available on the open shelf. ↩

-

Genealogy research resources are available at http://libguides.nl.sg/. ↩

-

FamilySearch is accessible at www.Familysearch.org. ↩

-

This organisation’s website can be be accessed at www.singaporegenealogy.org. ↩