Life in Death: The Case of Keramats in Singapore

Keramats (shrines) have endured the fast-paced changes characteristic of Singapore’s urban progress and development. Over the centuries, keramats have obtained a symbolic significance that transcends the vibrant social fabric of multiple religions and cultures.

It is the religious syncretism and symbolism of keramats that allow these relics to still remain relevant to Singaporeans in this modern era. Embedded within the keramats are the ebb and flow of Singapore’s history and its continuing evolution. In essence, the keramat is not just a monument of remembrance for the dead, but also a rallying point for the living.

Despite being hidden away in the folds of Singapore’s concrete jungle, keramats and keramat-worship are far from being entrenched in the forgotten annals of history. The entrances to many of these keramats are often “invisible”, seemingly quiet, offering respite from the heat and throngs of people. What we mistake for wooden huts, serene and seemingly forgotten, belie the hopes, dreams and prayers of those who have taken a chance to lay their most personal needs and desperation in the forms of fragrant offerings at the foot of a grave of a person they have never met, much less a faith in which they do not believe.

Surviving the Dredges of Urbanisation and Commercialisation

— W.W. Skeat Malay Magic (1984, p. 62)

Evidence of keramats pre-dates even the arrival of the British1. The sheer variety of existing keramats at important historical sites such as Fort Canning Hill (Keramat Iskandar Shah), the vicinity of the then-river mouth (Makam Habib Noh at Mount Palmer before reclamation) and elsewhere inland attests to Singapore’s important position in the sea routes of the 18th century. It reveals Singapore’s role in the wider maritime world which encouraged a porous and plural society. Despite their long history, keramats have managed to survive in the fast-changing urban landscape characteristic of Singapore. Keramats located in prime estates such as those belonging to Habib Noh at Mount Palmer, Keramat Iskandar Shah at Fort Canning, Keramat Dato Syed Abdul Rahman (or known simply as the Malay/Kusu Keramat) and the Da Bo Gong Temple (Merchant God or God of Prosperity) on Kusu Island have managed to retain their relevance and thwarted the (often fatal) insurgence of tourism brought about by the imaginings of the tourism industry.2 More often than not, these keramats and shrines are fully funded by the kind donations of devotees who come to offer their prayers and/or give thanks for a bountiful harvest believed to have been derived from their patronage of these shrines. The key to their survival despite Singapore’s cutthroat urban land use policies may lie in the symbolism that appeals to the various races, cultures and religions in Singapore.

The religious syncretism and symbolic significance embedded in these keramats have ensured their survival through the years. Of interest is also local history that has seeped into the crevices of these tombs, which may provide an insight into Singapore life before the arrival of the British. The keramats provide a key understanding of how the different cultures and religions interacted, and offered a space where all faiths could be practised and intermingle freely. The interaction of the different cultures and localisation of the various religious influences have undoubtedly helped in the socialisation of the various communities in Singapore (Choo, 2007; Goh, 2011) then, now and possibly even the future.3 The transethnic and transcultural symbolism prevalent in keramats bear testament to the fluid and plural maritime world that was the bedrock of premodern Singapore (Goh, 2011).

This article focuses on the more prominent keramats such as Keramat Iskandar Shah, Makam Habib Noh and the two keramats on Kusu Island. These keramats have been acknowledged and mentioned in the Singapore street directories and other surveys of local sites of interest, such as D.S. Samuel’s Singapore’s Heritage Through Places of Historical Interest (2010) and the National Parks Board’s Walking Trail.4

The term “keramat”, derived from the Arabic term karamah, generally refers to the sacred nature of a person, animal, boulder, trees, etc., but takes on different meanings when applied in different contexts (Skeat, 1984; Marsden, 1812; Wilkinson, 1959). This article specifically examines the term “keramat” when used on a person to indicate and imply sacred divinity and referring to the tombs of revered and holy persons, especially the early Arab missionaries. These keramats are not mere graves, but they carry a greater significance that applies to a wider audience beyond the individual. Whilst these sacred sites are still known as “keramat” today, the nature of keramat-worship has taken on a different facet.

Evolving Definitions of Keramat and Keramat Worship

The foundations of the practice of keramat (saint) worship derived from early Sufi Islam and pre-Islamic animistic traditions. Worshippers believe in semangat5 (an intangible mystical force embedded in objects, totems or nature), and attached the Arabic-derived title of keramat to accord a certain status and venerability to superstitious sites. The term was subsequently absorbed into Bazaar Malay (Rivers, 2003), also known as colloquial Malay or Bahasa Melayu Pasar. These sites, particularly the shrines and tombs of Sufi masters regarded as saints, are frequented as part of a pilgrimage to either beg for a wish to be granted, or to pay respects and give thanks for the fulfilment of the said wish. Although this is in direct opposition to the Islamic belief of the singularity and One-ness of God, keramat worship carries an undercurrent of Islamic reverence for saints who attain barakah, or semi-devine power, due to their extreme piety and devotion to God (Cheu, 1996). As such, these saints are sought after even in death by those in need of advice and assistance.

Keramats—burial grounds of persons believed to be saints and rulers of dynasties—were revered beyond their native worshippers, even by the colonials themselves who, short of providing offerings, acknowledged and respected these sacred sites. Raffles referred to Bukit Larangan as “the tombs of the Malay Kings”.6 In his letter to the Duchess of Somerset, he remarked that should he pass on while on duty, he “preferred ascending the Hill, where if my bones must remain in the East, they would have the honour of mixing with the ashes of the Malayan kings”.7 The keramats and Bukit Larangan were regarded as the “only remains of antiquity” to Singapore’s precolonial history.8

Although initially regarded as a rural Malay practice by colonial scholars (Winstedt, 1924; Skeat, 1967), other forms of such veneration—that is, ancestral and deity worship—were already practised by Chinese religionists and Hindus in British Malaya. The central principle in such worship is the propitiation of guardian spirits, receiving protection against calamities and ensuring abundant harvests or profits (Cheu, 1996). John Crawfurd, on his visit to Bukit Larangan during a stopover in Singapore en route to Siam, noted that a crude shrine had been erected over the tomb of Iskandar Shah so as to allow Muslims, Hindus and Chinese (religionists) to pay homage.9 Several articles in The Straits Times10 in the early 20th century, such as “Singapore’s Keramats: Wonder-Working Shrines Sacred to Many Nationalities” (11 June 1939), which offers a thorough survey of the existing keramats in Singapore and its surrounding islands, also indicated that such keramats and shrines were patronised by all and was a subject of interest to the public.

This syncretism was also noted by renowned French scholar, Henri Chambert-Loir, who observed that “mausoleums of Muslim saints were built upon Savaite temples and Buddhist stupas in Java as early as the 15th and 16th century”.11 The keramat, in essence, is a prime example of a hybrid practice that is emblematic of the spread of this syncretic pseudo-Islamic custom in maritime Southeast Asia (Goh, 2011). Its spread, from its initial adaptation of Sufi and animistic origins, began to morph in tandem with the various cultures and belief systems of immigrants to Singapore and the wider southeast maritime region (Rivers, 2003).

Keramats as Spaces for Transcultural Contact and Interaction

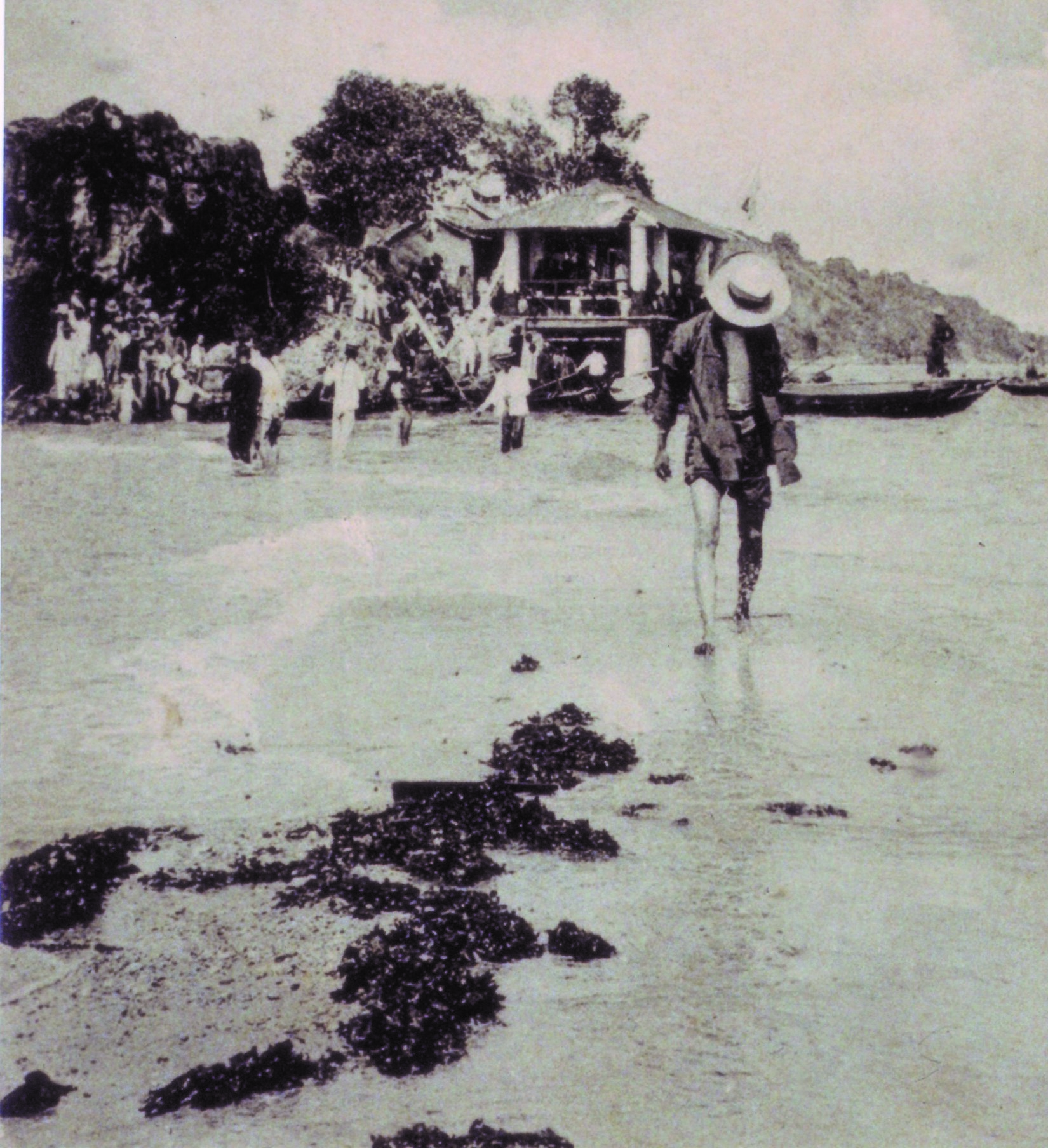

The keramats on Kusu Island (previously known as Pulau Tembakul)12 provide an interesting glimpse into the hybridity that transcends both race and religion. The annual month-long Kusu pilgrimage to the Da Bo Gong (Tua Pek Kong) Temple and the Malay Keramat attracts pilgrims from as far as Hong Kong.13 The latter is supposedly the tomb of Syed Abdul Rahman, an Arab traveller who, according to legend, was saved by a tortoise during a treacherous journey and brought to Kusu Island. He was eventually laid to rest there. The Chinese have come to worship this keramat as the native Malay equivalent of Da Bo Gong, and refer to it as Datok Kong, or Na Du Gong (Loo, 2007). The term “Datok Kong” is indicative of the Sino-Malay interactions entrenched in keramat worship: “Datok” and “Kong” both mean “grandfather” in Malay and Chinese respectively, and are used generically for the worship of a venerated person of Malay or native origin (Cheu, 1996). Worshippers are also not limited to any specific class, and include wealthy businessmen, entrepreneurs or ordinary laymen desiring better riches and luck in life.

Sino-Malay influences can also be seen in the decoration of this keramat: the emblematic green crescent and star indicative of the Islamic faith are juxtaposed with the yellow banner with bold red Chinese characters that read “Na Du Gong” hanging above the keramat. Even the donation box is inscribed with “Waatlaa [sic] Heng Heng Lai” (Prosper! May good luck come!). Burning joss sticks and incense adorn the front of the keramat, left behind after worshippers have made their prayers and given their due respect. Also, as a form of respect, visitors are encouraged not to bring any food or lard to the island.14 It is probably wise to note here, despite the supposed origins of this keramat, that Muslims no longer visit the Kusu Keramat. Cheu (1996) reiterates and concludes in his paper that “more and more Chinese have adopted the keramats as less and less Malays worship them in the wake of Islamic revival in the 1980s”. Kusu Keramat is relatively well known by the generic name of “Malay Keramat” (nothing about the shrine is in fact Malay except its caretakers, since the supposed Syed Abdul Rahman is Arab) and not tied to a known saint, indicating that this keramat has been popularised by Chinese religionists.

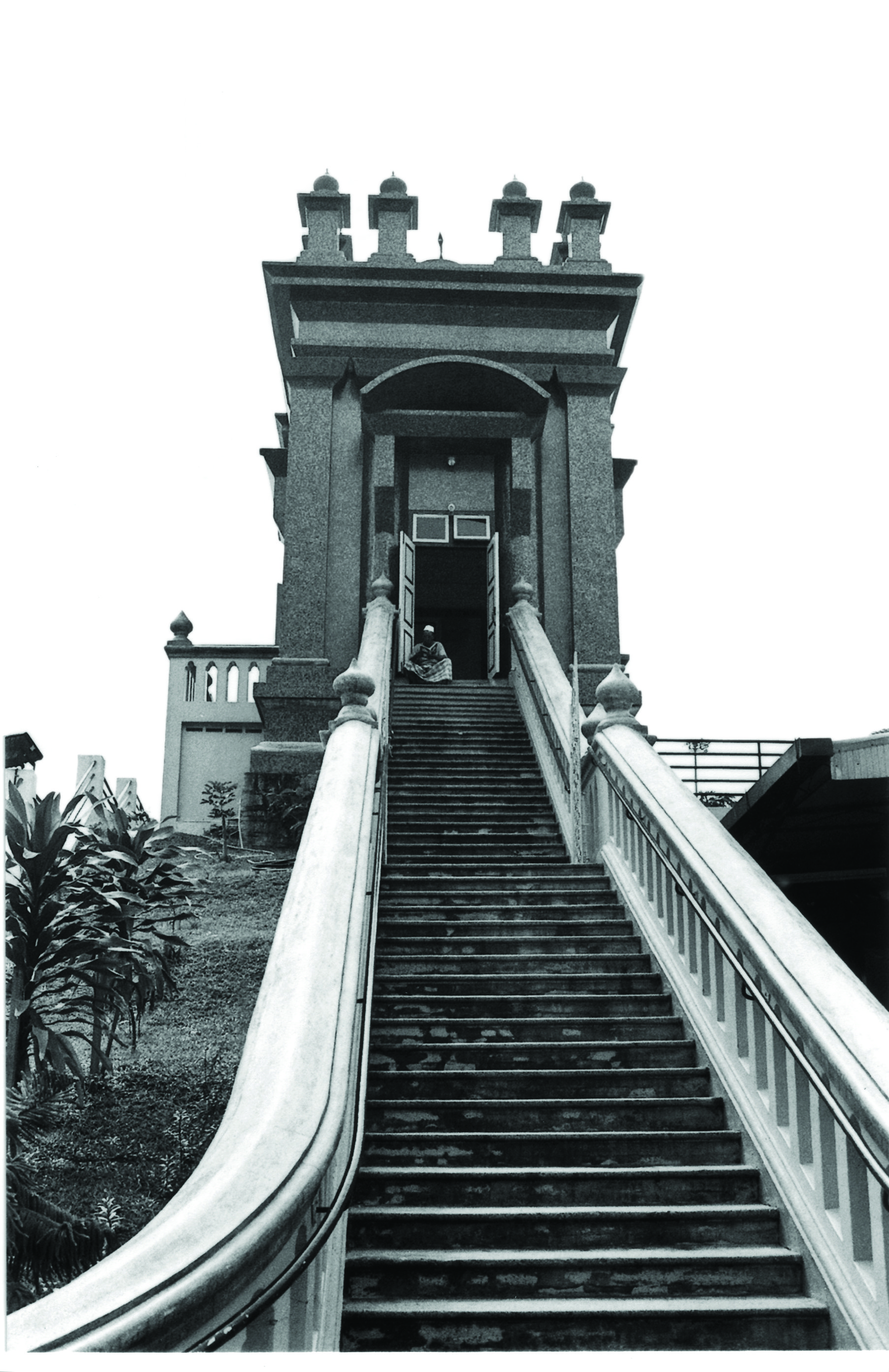

Makam15 Habib Noh at Mount Palmer within Singapore’s Central Business District is another important site. Quite unlike the Kusu Keramat, Makam Habib Noh is anchored by a definite personality, the saint Habib Noh16, who is highly revered in Muslim circles. Still, worshippers at the keramat are not unlike those at Kusu. Offerings of bananas, yellow rice, bottles of opened water (to be blessed) and burning incense are just some of the offerings found at the keramat. The variety of offerings is also indicative of the different cultures that frequent them.17

The scene that greeted me on my visit was pleasantly surprising, given the fact that this keramat is located within the compounds of the Haji Mohd Salleh Mosque: in the left corner, an elderly Chinese lady was kneeling in prayer with her hands clasped in fervent concentration. The grandchild she brought with her played by himself by the doors of the inner room. After she was done, she stood, placed her hands on a grave marker (batu nisan ), and bowed before leaving. At the other end of the keramat was an Indian Muslim couple engrossed in reading the Quran. Shortly after, they stood and each took a grave marker, plastered their foreheads to it and bowed their heads, lips moving feverishly but silently. Around the keramat were a total of five opened bottles of water, fresh flowers and other offerings. I realised then, regardless of the purposes and forms of worship, that keramats are sacred precisely because they are tangible focal points in a community, a place to harbour intangible dreams. It was a place to ask, beg, and give thanks.

Keramats as Repositories of History

It is perhaps this fluidity in which keramat worship is practised that has kept the keramats in existence up until today. It offers a space where different groups can engage, influence and contribute to the significance of a physical site in their own way. This aspect of organic syncretism and mutual respect between cultures attests to the fact that keramat worship is “a repository of the deep structures of trans-ethnic cosmologies and shared socio-moral orders within local society despite their erasure by modern bureaucratic powers” (Goh, 2011). It has survived even without ardent state promotion or efforts by the Singapore Tourism Board, and has been kept alive without reenactments for tourists or the exoticisation of native practices. Loo (2007) even notes in her survey of the keramats on Kusu Island that the erected signboards indicate little of the rich history of the island. The survival of the keramats is a direct result of individuals who frequent and deem them important. Keramats have managed to remain relatively undetected and unharmed by consumerist tourism and yet relevant enough to serve the different communities. They are truly sites for the people because of their unadulterated and underrated history.

The keramats claim their significance and become ingrained into public consciousness through a larger historical framework grounded in the cultural plurality and fluidity among all races and faiths. Bukit Larangan, the site of Keramat Makam Iskandar Shah, is also rich with Singapore’s ancient history. According to pottery fragments uncovered by archaeologist John Miksic, the grave might have belonged to Sri Tri Buana (Lord of the Three Worlds; c. 1299–1347), founder of the Singapore dynasty until Iskandar Shah fled Singapore (Rivers, 2003). This legendary ruler is recorded in the Sejarah Melayu (The Malay Annals).

More importantly, however, these keramats exist beyond the personality that they were erected for by serving a larger audience that is not limited to any specific group. Over time, keramats absorb and incorporate the traits of the different cultures and faith that make up the social fabric of Singapore. In fact, the persona attributed to a keramat is usually that of its caretaker, who devotes his/her life in the service of the said saint or keramat.

Oral and written accounts of “miracles” borne out of worshipping the keramat, or relating to keramat itself, keep the keramats in our memory. Although research of the origins and documenting such keramats are still lacking, numerous scholars and individuals have begun the arduous efforts to claim these sites as historical and integral to Singapore’s precolonial and ethnographic history.

Keramats are a lived reality and a window to Singapore’s past. From a sociological perspective, they are an oasis for varying cultures, traditions and histories to blend together and coexist, merging different practices that revolve in and around the same physical space. Keramats are evidence of the hybridity and syncretic culture that form the bedrock of Singapore society from its inception even before the colonial era. They showcase ground-up efforts and an understanding of faith, popular religion, and are the real-life definition of religious and racial harmony. Its underrated and non-commercial nature has proven to be a boon for its existence, yet cannot guarantee its future. In Singapore’s dense urban environment, it is difficult to justify the use of space that can neither be rationally explained nor commercially utilised. In the case of keramats, death is a starting point and a beginning of another chapter in history. They record, absorb and bear witness to the changing practices and milieu of their surroundings. Should they finally be deemed irrelevant in the future, only then will they finally hear the death knell as keepers of secrets to the past.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the contributions of Ms Janice Loo, Associate Librarian, National Library Content and Services division, and Mr Haikel Fansuri for their comments in reviewing this paper.

REFERENCES

A Guide to Singapore’s Ancient History Walking Trail at Fort Canning Park. National Parks Board. Retrieved from National Parks Board website.

Cheu, Hock Tong (1996/1997). Malay Keramat, Chinese Worshippers: The Sinicization of Malay Keramats in Singapore. Singapore: National University of Singapore, Department of Malay Studies. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Chia, Jack Meng-Tat. (2009, December 2). Mananging the tortoise island: Tua Pek Kong Temple, pilgrimage, and social change in Pulau Kusu, 1959–2007. New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies, 11, 72–95.

Choo Liyun, Wendy. (2007). Socialization and localization: A case study of the Datok Gong cult in Malacca. Retrieved from nus.edu.sg website.

Cornelius-Takahama, Vernon. (2016, September 16). Kusu Island Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia.

Foy, Geoff (n.d.). Chinese belief systems: From past to present and present to past. Asia Society. Retrieved from Asia Society website.

Goh, Beng Lan (2011). “Spirit cults and construction sites: Trans-ethnic popular religion and keramat symbolism in contemporary Malaysia” in Engaging the spirit world: Popular beliefs and practices in modern Southeast Asia (Asian Anthropologies: v. 5). New York: Berghahn Books.

Page 34 Advertisements Column 1. (1992, October 17). The Straits Times, p. 34. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Loo, Chew Yen Janice. (2007). The cultural assets of Kusu Island. [Unpublished paper]

Magiar Siemen. (1970, January 3). Bendera Jepun putus dekat keramat tertua Singapura. Berita Harian, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Marsden, William. (1812). A dictionary of the Malayan Language, in Two Parts, Malayan and English, and, English and Malayan. London: Cox and Baylis. Retrieved from BookSG.

Mohammad Ghouse Khan Surattee. (2008). The Grand Saint of Singapore: The Life of Habib Nuh bin Muhammad A-Habshi. Singapore: Al’ Firdaus Mosque. (Call no.: RSING 297.4092 GRA)

Mohd Taib Osman. (1989). Malay folk beliefs: An integration of disparate elements. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa and Pustaka. (Call no.: RSEA 398.4109595 MOH)

Month-long Kusu pilgrimage begins next week. (2012, October 9). The New Paper, pp. 8–9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Rivers, P.J. (2003). Keramat in Singapore in the Mid-twentieth century. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 76 (2) (285), 93–119. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Samuel, Dhoraisingam. (2010). Singapore’s heritage: Through places of historical interest. Singapore: The Author. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 SAM)

SINGALOND. (1939, April 11). Kramats of Singapore. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Skeat, W.W. (1984). Malay magic: Being an Introduction to the folkore and popular religion of the Malay Peninsula. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 398.4 SKE)

Wilkinson, R.J. (1959). A Malay-English Dictionary. London: Macmillan. (Call no.: R 499.230321 MAL)

Winstedt, R.O. (1924, December). “Karamat”: Sacred places and persons in Malaya. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 2 (3) (92), 264–279. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Yahya. (1939, June 11). Singapore’s keramats: Wonder-working shrines sacred to many nationalities. The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

NOTES

-

By the time Raffles landed in Singapore in 1819, Bukit Larangan (Forbidden Hill; now known as Fort Canning Hill) was already the ancient burial ground of the royal sultanate. The tomb of Iskandar Shah, said to be the fifth and last ruler of Simhapura (Sankrit term ‘सिहपुर’ from which the name Singapore was derived) still resides at the top of Fort Canning. Jalan Kubor was also another site of royal burial. Early plans of Singapore by G.D. Coleman (1836) indicate the parcel of land as “Tombs of the Malayan Princes”, quoted in Rivers (2003). ↩

-

The Singapore Tourism Promotion Board (now known as Singapore Tourism Board) did plan to market the “largely under-utilised” Southern islands as resorts for the rich in as early as 1989. Kusu Island was not initially considered for these plans as it was recognised as a pilgrimage site. (The Straits Times, 17 September 1992, p. 34.) ↩

-

Early colonial surveys indicate the existence of keramats and their trans-ethnic worshippers. For an in-depth reading, please refer to Richard Winstedt’s The Malay Magician: Being Shaman, Saiva and Sufi (1961) and Walter W. Skeat’s Malay Magic (1984). ↩

-

National Parks Board. “A Guide to Singapore’s Ancient History Walking Trail at Fort Canning Park”. ↩

-

See Mohd Taib Osman. (1989). ↩

-

C.E. Wurtzburg, Raffles of the Eastern Isles, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1954, p. 620, quoted in P.J. Rivers (2003, p. 105) ↩

-

John Crawfurd, Journal of an Embassy to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China, KL: Oxford University Press, 1967, p. 46, quoted in Rivers (2003, p. 105) ↩

-

Various other articles were written over the years that showcased and surveyed these keramats or were queries from residents to find out more about the keramats in Singapore. Among others, were The Straits Times, ‘Kramats of Singapore’ (11 April 1939, p. 10) and Berita Harian, ‘Bendera Jepun putus dekat keramat tertua Singapura (Japanese flag rips off at the oldest keramat in Singapore’ (3 January 1970, p. 4). ↩

-

Chambert-Loir, Henri. (2002) “Saints and ancestors: The cult of Muslim saints in Java” in The Potent Dead: Ancestors, Saints and Heroes in Contemporary Indonesia, quoted in Goh (2011, p. 154). ↩

-

For a better understanding of Kusu Island, please refer to National Library Board. (2016, September 16). Kusu Island written by Vernon Cornelius-Takahama. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

Month-long Kusu pilgrimage begins next week. (2012, October 9). The New Paper, pp. 8–9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The New Paper, 9 Oct 2012, pp. 8—9. ↩

-

The terms makam and keramat, though not synonymous, are used interchangeably in a colloquial context. For the purposes of this paper, we will retain the interchangeable nature of these terms as the site is regarded as both a makam (mausoleum) and a keramat by different groups under different contexts. ↩

-

For an in-depth history regarding Habib Noh and his shrine, please refer to Muhammad Ghouse Khan Surattee. (2008) The Grand Saint of Singapore: The Life of Habib Nuh bin Muhammad Al-Habshi. Singapore: Masjid Al-Firdaus. ↩

-

Please refer to Cheu (1996, p. 11) “Table 1: Beliefs and Practices in Malay Keramat and Datuk Kong” for a list of the different nuances and types of offering presented by the different cultural groups. ↩