Grave Matters: The Burial Registers in Singapore

A little-known historical resource, burial registers provide a glimpse into the lives and conditions in early Singapore.

On 11 January 1924, amidst pouring rain, grave diggers at Bidadari Christian Cemetery lowered the bodies of Cecilia Lee Yew Seah, Jeanne Yon Ah Soo, M. Lee Yon Rie and Jules Hoh Chin into their shared final resting place. As two nuns in their black habits from the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus (CHIJ) stood silently witnessing the burial of the four infants, the oldest of whom had only been seven months old, the gravediggers started shovelling soil back into grave number 363 of the French Roman Catholic Pauper division. This was their only burial of the day and they were eager to get out of the rain.1 After all, infants from the convent orphanage seemed to die like flies. The nuns would come again tomorrow to deliver more baby corpses for burial.

Cecilia Lee Yew Seah, Jeanne Yon Ah Soo, M. Lee Yon Rie and Jules Hoh Chin were individuals of no particular significance in Singapore’s history. They were, however, four of the 584 infants buried in Bidadari Christian Cemetery in 1924, a year in which the cemetery recorded a total of 960 interments. Together with death certificates, birth certificates, grave inscriptions and obituaries, burial registers are commonly used to trace genealogy.2 However, the use of burial registers in writing social history has gone largely undiscovered. The astonishingly high number of infant deaths and the circumstances under which they died are but one of the fascinating stories that can be derived from the burial registers.

Burial Registers in Singapore

Among the sources that can be used in the writing of Singapore history, burial registers are unique. Factual by nature, morbid in character, burial registers present seemingly dry and dusty data sets that have the potential to reveal fascinating patterns about society upon further investigation. Although burial registers are useful in tracing genealogical ancestry, they are vastly overlooked resources in the construction of Singapore’s social history.

The burial register, alternatively called a burial or cemetery record, comprises a list of people buried in a particular cemetery, where certain information is recorded according to state-dictated categories. These categories include the following:

• division of the cemetery where the deceased is interred

• grave number

• religion

• nationality

• rank or profession

• married or single

• date of death

• date of interment

• name of deceased

• sex

• age

• place of residence

• cause of death

Used in tandem with other “traditional” resources such as state records and newspapers, such records of deceased individuals that collectively formed society has the ability to “resurrect Singapore life as lived” while opening new areas of research.3

In the past, as in the present, the state kept the burial registers for administrative purposes to account for every burial that took place. The British government initiated this system of record-keeping with the establishment of one of the first few public cemeteries in Singapore, the Bukit Timah Road Old Christian Cemetery in 1865. Such records were part of the mechanics of colonialism, which saw the gradual extension of the British government into documentation procedures such as census taking, standardising languages and keeping administrative records. The right to govern was determined by the knowledge that society could be understood and represented as “a series of facts” that classified the local population.4 Over time, the colonial government compiled and reproduced huge bodies of information that legitimised their right to rule and became the definitive body of knowledge upon which policies were based.

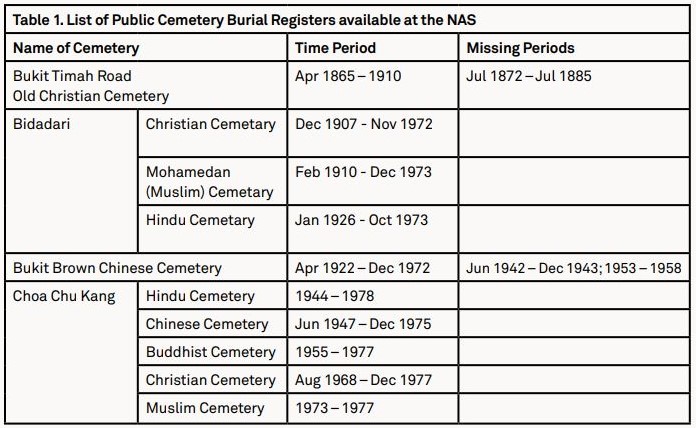

The legacy of colonialism has made historical inquiries into the lives of the early forefathers of Singapore much easier. The National Archives of Singapore maintains burial records (see Table 1) of all public and state-governed cemeteries, the earliest from the Bukit Timah Road Old Christian Cemetery. After its closure in 1907, other municipal cemeteries such as Bukit Brown Chinese Cemetery and the Christian, Muslim and Hindu sections of Bidadari Cemetery were established. These records end in the 1970s, when all burial grounds in and around the city area were closed to conserve “scarce and valuable” land given “the needs and pace of national development”.5 An alternative was offered in the state-owned cemetery at Choa Chu Kang, which was erected in 1944 and included Hindu, Chinese, Buddhist, Christian, and Muslim cemeteries by the 1970s. This is the sole surviving public cemetery in Singapore and is still in use today. Its records stop in 1978, given the “25-year international archival benchmark” blocking access to unclassified public archives within that timeframe.6

Living and Dying in Singapore: The Convent Orphanage

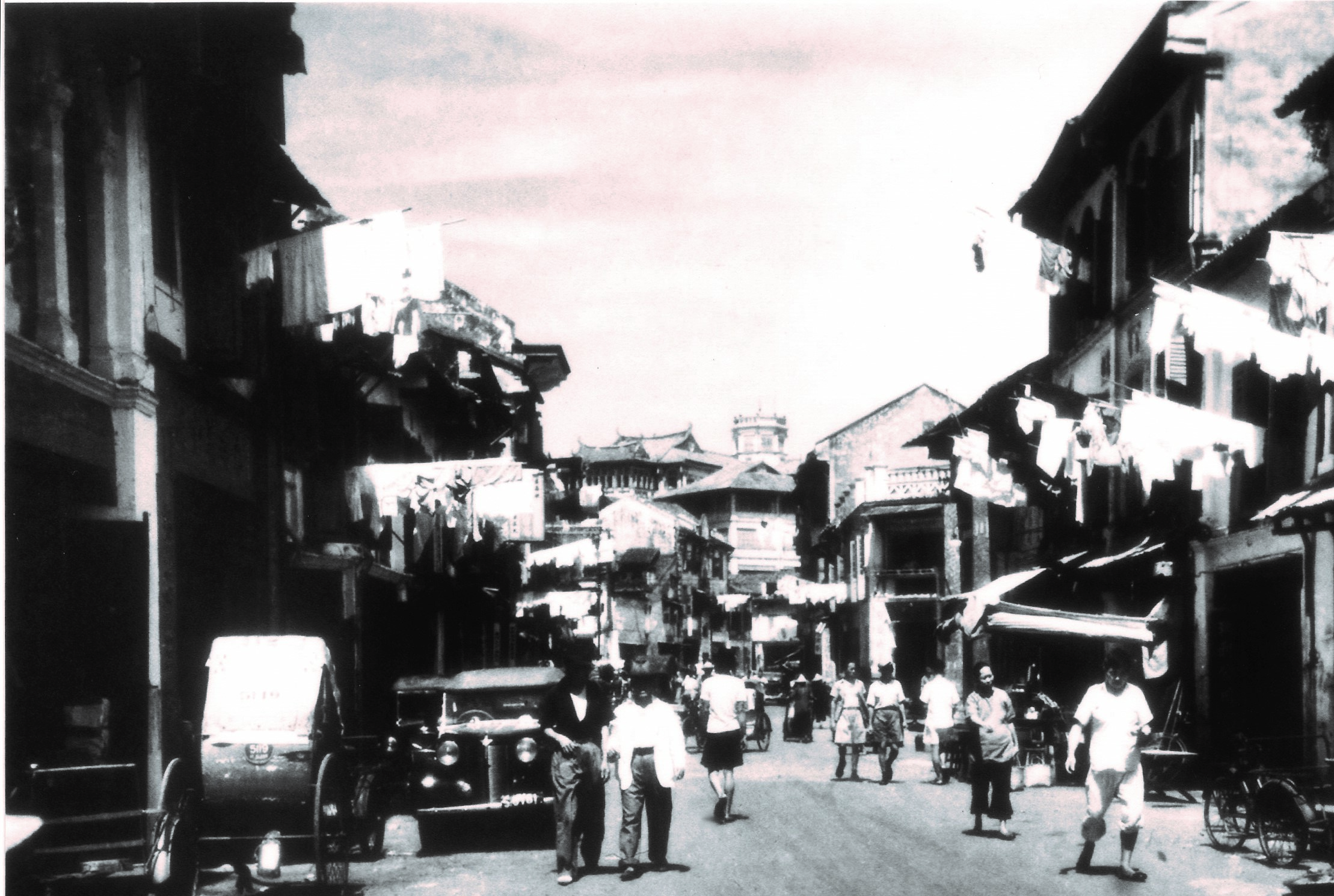

Early 20th-century Singapore was not a pleasant place to live in. In the rural plantations, there were dangerous animals, unsafe working conditions and tropical diseases to contend with. Such diseases were exacerbated a hundredfold within the overcrowded municipal limits, within which 83 percent of the population resided on 13 percent of the land area of Singapore. Poor sanitation, combined with overcrowded housing facilities, caused the rampant spread of diseases that periodically cut huge swathes through the population.

Burial registers illuminate the state of health in society, and are useful for recreating a more tangible lived experience of the inhabitants of Singapore. Health was recognised to be of paramount importance. For the Asian plebeian classes, health was the most important asset they possessed – “a man who sold his strength for a living ought guard his body: his physique was everything”.7 To the British colonial government, healthy labourers had greater economic value and “health services were established and operated precisely to maintain health in order to meet the labour needs of the economy”.8 Despite its importance, health was easily threatened by the high incidence of disease and mortality that was in many ways shaped by the “inequalities, powerlessness and poverty produced by the structures of colonialism”.9 Examining colonial records such as burial registers and exploring the stories behind some of these data sets provide great insight into British attitudes towards the inhabitants of Singapore. Burial registers thus draw attention to the state policies and institutions that shaped the health environment of colonised subjects, and contribute to the construction of a social canvas of the lives and deaths of ordinary people of that time.

At a glance, the methodical listing and statistical nature of the burial records “silence the undocumented, ordinary and unremarkable lives and deaths of the men, women and children of the colonies”.10 However, through an analysis of the categories of “age”, “gender”, “cause of death” and “residence”, patterns of morbidity and mortality begin to emerge. Health and illness are “socially embedded phenomena” within these patterns and they “reflect the singular circumstances of time and place”, which helps in understanding society at a particular point in time.11 This proves particularly relevant when examining the Bidadari Christian Cemetery burial records of 1924, which reveals an astonishingly high infant mortality rate originating from the convent orphanage.

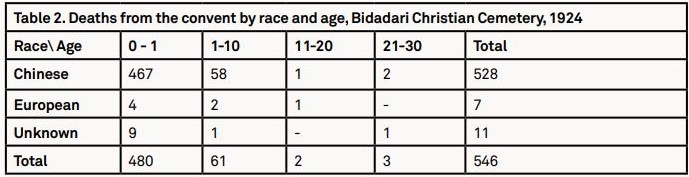

Though 1924 had the lowest infant death rate in a decade, infant deaths still accounted for 25 percent of the total number of deaths in that year, a clear indication of the deadly effect of the external environment upon infants (defined as a baby between zero to one year old). The burial registers of the Bidadari Christian Cemetery in 1924 recorded a startlingly high number of 584 infant deaths out of 960 interments. Of these 584 infants, more than 80 percent, or 480 infants, had resided in the CHIJ convent in their tragically short lives. Only through the burial registers (see Table 2) do the shocking numbers of infant deaths come to light, allowing for an unravelling of the mystery surrounding the huge numbers of infant deaths from the convent.

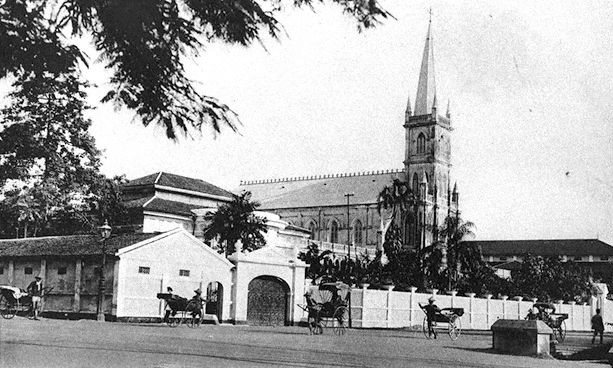

The large numbers of infant deaths did not originate from the convent itself, a mission school established in 1854 by the Charitable Sisters of the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus to “educate girls of all classes”.12 The infant deaths came from the convent orphanage, which had been established together with the school. Unwanted babies, wrapped in newspapers or rags, were usually abandoned at the side gate of the convent, known as the “Gate of Hope”.13 The name of the gate turned out to be an irony as the majority of babies abandoned there perished. Prior to their deaths, the babies were baptised into the Roman Catholic faith and were given French Roman Catholic names.14 This would account for the disproportionately large numbers of Christian deaths in the census report of 1921 when the Christian population of Singapore comprised only five percent of the population.15

On the assumption that names were an accurate reflection of racial identity, of the 480 infant deaths, the majority were Chinese (467), whose race could be inferred from Chinese names such as Gabrielle Wong Quek Soo, Joseph Loh Kum Hong and Therese Koo Tiong. The large numbers of Chinese infant abandonments at the convent could be due to a variety of factors, but were in all likelihood linked to cost and cultural beliefs. Chinese families who abandoned their child were usually too poor to afford funeral expenses, and it was a common belief that a death in the house would bring misfortune.16 By abandoning their child at the convent, parents still had a thread of hope that their child would survive or, at the very least, be given a proper funeral. This led to the disproportionately large numbers of abandoned babies at the convent.

Within this group of 467 Chinese infants, the number of female infants doubled male infants at 311 females to 156 males. This was due to the Chinese cultural belief of preferential treatment of boys over girls.17 Because boys were regarded as more valuable, they were abandoned only when on the brink of death. This meant that while fewer male infants were abandoned, practically all male infants who were abandoned at the orphanage would die. In any case, despite the nuns’ care, most abandoned babies were “so undernourished and so ill that they [had] little chance of survival”.18 Though current literature records that the sisters cared for 200 children in 1892, and 400 children by 1936, the burial registers prove that the chillingly high number of 584 infant deaths in the single year of 1924 far exceeded the ones who lived.19

Such findings reveal that the convent orphanage was established within the framework of colonial structures and reflected societal conditions that had necessitated a private institution for infant welfare. The colonial government evidently provided little aid in improving the environment for infants and in providing adequate healthcare. From the Administrative Records of the Singapore Municipality, the evidence gathered by the European District Visitors over a 12-year period proved that most babies were born healthy.20 However, about a quarter of them died within the first year, which meant that many of the infants had died from preventable causes.21 While infant deaths could be ascribed to a variety of causes, such as inherited diseases, improper birth procedures, inadequate feeding and neglect, unsanitary conditions were more often than not responsible.22

Health was closely intertwined with place of residence, which could determine how one lived and died. Most of the babies abandoned at the convent came from “cursed cubicle[s]” within “slums of Chinatown, the squatter areas in Silat Road and the poor rural areas”.23 Such cubicles were usually “dark and ill-ventilated”’ rooms that could easily be repartitioned to accommodate more tenants.24 The erection of such partitions “extended to the ceiling, cutting off even a modicum of light and air”, creating ideal conditions for the spread of respiratory diseases.25 With no proper town planning, these slums also grew haphazardly, with “numerous immense blocks of houses stretch[ing] from street to street, without a single lane, alley or court of any description”.26 This obstructed the construction of an effective sewage disposal system and hindered the establishment of an urban water supply, contributing to the proliferation of waterborne diseases. Such conditions are reflected in the causes of infant deaths: premature births and convulsions, numbering 139 and 117 cases respectively, accounted for the largest causes of death. Premature births and convulsions were usually due to poor health or poor nutrition of the mothers and infants, in which environmental factors that encouraged the spread of diseases had a significant part to play. Enteritis, an infection caused by the consumption of contaminated food and water, and pneumonia, an infectious airborne disease easily spread in close living quarters, also claimed the lives of 82 and 58 infants respectively.27 The environment in 1924 thus created ideal conditions for diseases to befall those with weak immune systems, making pregnant mothers and infants the most susceptible.

Colonialism lay at the root of the problem of overcrowded housing and the spread of diseases. The British had fundamentally changed the social landscape through colonialism, which had brought an influx of migrants and accompanying new pathogens. However, they had not developed an urban infrastructure to accommodate the rapidly increasing population. Despite recognising the dire state of the housing situation in Singapore by 1910, as highlighted by W.J. Simpson’s report on the sanitary condition of Singapore in 1907, “no real attempt [was] made to grapple with the problem” by 1924.28 Instead, blame was cast upon the “Asiatic ignorance and apathy” of those who were “filthy in their habits beyond all European conceptions of filthiness”.29 Even though overcrowding housing practices affected the health of the poor adversely, they lived in such conditions out of necessity and the lack of other affordable housing options. Since “neither the colonial government, the municipality, nor the private sector were prepared to shoulder the expense of providing housing for the Asian labouring classes”, the poor had to adapt through maximising the little amount of available space in the city.30

Because the colonial government was unprepared to undertake expensive large-scale sanitary reforms to revamp the slums, they instead focused their efforts on the small-scale establishment of two infant welfare clinics in 1923. These clinics, located at the Registration and Vaccination depots on Prinsep Street and Kreta Ayer Street, which saw 5,338 consultations in 1924.31 This was a mere third of the 14,398 babies born that year, which indicated that the majority of babies had not undergone vaccinations or treatment. In the absence of mandatory health measures, the convent orphanage was a private institution that functioned as an alternative solution to the inadequate public healthcare system for infants.

Roland Braddell, a visitor to Singapore in the 1920s, immortalised the uplifting courage of the convent nuns in caring for abandoned infants in his writing:

A feeling of security and peace will descend upon you, with a vast respect for the courage and self-sacrifice of the quiet nuns… In the Convent unwanted babies of all races are left and are cared for… what a tremendous debt Singapore owes to the little ladies of the Convent.32

Without having examined the burial registers, one might never have had cause to question the effectiveness of the orphanage in tending to these babies or the condition of the babies at the time they were delivered to the Gate of Hope. Upon further investigation, one discovers that the convent orphanage was situated within a larger framework of colonial healthcare, housing discourse and Chinese belief systems. Such insights are privy to the historian who analyses the burial registers over time to uncover patterns of morbidity and mortality that are unavailable from other sources. Further investigation in conjunction with the use of other sources reveals the dynamics within this discourse of health. Such everyday experiences of sickness and death as evinced from the burial registers contribute to constructing a historically richer picture of life in 1924.

Burial Registers as Historical Resource

As a historical resource, burial registers shed light on the morbidity and mortality of the inhabitants of Singapore, which is the subject matter and raison d’être of the registers themselves. However, burial registers also offer insights into the power structures, prejudices and perceptions of state authority. This information helps in understanding the lived experience of the inhabitants of Singapore, while acting as a social commentary on the governance of the state. In particular, the records of the early burial registers yield rich data because they reflect the worldview of the British colonial authority. Burial registers of later years follow a standardised template that, while still of use in understanding more about a certain community, are no longer as reflective of society. Ultimately, the value of the burial register lies not in what it can tell us about history, but what questions it can enable the historian to ask that will offer a richer depth to history as we know it.

REFERENCES

Primary Sources

Unpublished Official Records

Administration reports of the Singapore Municipality, 1924.

Burial registers of Bidadari Cemetery, 1918–1972.

Burial registers of Bukit Brown Cemetery, 1922–1945.

Burial registers of Bukit Timah Road Old Christian Cemetery, 1872–1895.

Burial registers of Chua Chu Kang Cemetery, 1955–1975.

CO273 Straits Settlements, Blue Book, 1924.

Published Official Records

Simpson, W.J. (1907). Report on the sanitary condition of Singapore. London: Waterlow and Sons. Retrieved from OneSearch catalogue.

Newspapers

The Straits Times, 1924–1983.

Secondary Sources

Books

Braddell, R. (1934). The lights of Singapore (pp. 69–90). London: Methuen & Co. (Call no.: RRARE 959.57 BRA; Microfilm no.: NL25437)

Chan., K. B., & Tong, C.K. (Eds.), Past times: A social history of Singapore. Singapore: Times Edition. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 PAS)

Cohn, B.S. (1996). Colonialism and its form of knowledge: The British in India (p. 4). New Jersey: Princeton University Press. (Call no.: R 954 COH)

Jaschok, M., & Miers, S. (Eds.) (1994). Women and Chinese patriarchy: Submission, servitude and escape. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. (Call no.: RSING 305.420951 WOM)

Kong, L., & Yeoh, B.S.A. (2003). The politics of landscape in Singapore: Construction of nation. New York: Syracuse University Press. (Call no.: RSING 320.95957 KON)

Loh, K.S., & Liew, K.K. (Eds.), The makers & keepers of Singapore history. Singapore: Ethos Books. (Call no.: RSING 959.570072 MAK)

Manderson, L. (1996). Sickness and the state: Health and illness in colonial Malaya, 1870–1940. New York: Cambridge University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 362.1095951 MAN)

Meyers, E. (2004). Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus: 150 years in Singapore. Penang: The Lady Superior. (Call no.: RSING q371.07125957 MEY)

Warren, J.F. (2003). Rickshaw coolie: A people’s history of Singapore 1880–1940. Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 388.341 WAR)

Wijeysingha, E., in collaboration with Reve Francis Rene Nicolas. Going forth: The Catholic Church in Singapore 1819–2004 (2006). Singapore: Titular Roman Catholic Archbishop of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 282.5957 WIJ)

Yeoh, B.S.A. (2003). Contesting space in colonial Singapore: Power relations and the urban built environment. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 307.76095957 YEO)

Articles

Middleton, W.R.C. (1911, July). The working of births and deaths registration ordinance. (1911, July). Malaya Medical Journal, 9 (3), 45–46. (From BookSG)

Dissertations

Singh, K. (1990). Municipal sanitation in Singapore 1887–1940 (p. 39). Singapore: NUS, Department of History. (Call no.: RCLOS 363.72095957 KUL)

NOTES

-

11 January 1924 was recorded to have had one of the highest rainfalls in that month.” Meteorological Observations, 1924”, Blue Book for the Year 1924 (Singapore: G.P.O., 1925), p. 479. ↩

-

Val D. Greenwood, The Researcher’s Guide to American Genealogy (Maryland: Genealogical Publishing, 2000), p. 61. ↩

-

James Francis Warren, Rickshaw Coolie: A People’s History of Singapore 1880–1940 (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 2003), p. 8. ↩

-

Bernard S. Cohn, Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1996), p. 4. ↩

-

Parliamentary Debates, 7 April 1978, quoted in Lily Kong and Brenda S.A. Yeoh, The Politics of Landscape in Singapore: Constructions of “Nation” (New York: Syracuse University Press, 2003), p. 57. ↩

-

Huang Jianli, “Walls, Gates and Locks: Reflections on Sources for Research on Student Political Activism”, in Loh Kah Seng and Liew Kai Khiun, eds. The Makers and Keepers of Singapore History (Singapore: Ethos Books; Singapore Heritage Society, 2010), p. 34. ↩

-

Lenore Manderson, Sickness and the State: Health and Illness in Colonial Malaya, 1870 – 1940 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), pp. 17–18. ↩

-

E. Wijeysingha in collaboration with Rev Fr. René Nicolas, Going Forth: The Catholic Church in Singapore 1819—2004 (Singapore: Titular Roman Catholic Archbishop of Singapore, 2006), p. 236. ↩

-

Wijeysingha, p. 261. ↩

-

Convent takes over 50 babies a month. (1948, September 2). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lily Kong and Tong Chee Kiong, “Believing and Belonging: Religion in Singapore”, in Chan Kwok Bun and Tong Chee Kiong, eds. Past Times: A Social History of Singapore (Singapore: Times Edition, 2003), p. 200. ↩

-

1500 babies abandoned in colony. (1950, January 4). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Maria Jaschok and Suzanne Miers, “Women in the Chinese Patriarchal System: Submission, Servitude, Escape and Collusion” in Maria Jaschok and Suzanne Miers, eds. Women and Chinese Patriarchy: Submission, Servitude and Escape (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1994), p. 7. ↩

-

Tragedy of Singapore’s unwanted babies. (1946, November 14). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Elaine Meyers, Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus: 150 Years in Singapore (Penang: The Lady Superior, 2004), p. 62. ↩

-

“Clinics”, Administration Report of the Singapore Municipality for the Year 1924 (ARSM) (Singapore: Straits Printing Office, 1925). ↩

-

“Clinics”, ARSM, 1925. ↩

-

W.R.C. Middleton, “The Working of the Births and Deaths Registration Ordinance”, Malaya Medical Journal, Vol. IX, July 1911, Part 3 (Singapore: The Methodist Printing House, 1911), pp. 45–46. ↩

-

Child Welfare Society. (1924, April 25). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; The Straits Times, 2 September 1948, p. 5. ↩

-

W. J. Simpson, Report on the Sanitary Condition of Singapore (London: Waterlow and Sons, 1907), p. 13. ↩

-

Kuldip Singh, Municipal Sanitation in Singapore, 1887–1940 (Singapore: NUS, Department of History, BA Hons. Academic Exercise, 1989/1990), p. 39. ↩

-

Brenda S.A. Yeoh, Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore : Power Relations and the Urban Built Environment (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 2003), p. 141. ↩

-

Convulsions and enteritis were indefinite headings that served as umbrella terms for deaths due to dietetic errors, malaria and tetanus, in “The Straits Settlement Medical Report for the year 1926”. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 27 Feb 1924, p. 8. ↩

-

“Clinics”, ARSM, 1924. ↩

-

Roland Braddell, The Lights of Singapore (London: Methuen & Co. Ltd, 1934), pp. 69–70. ↩