Singapore: A City of Campaigns

From work productivity, speaking Mandarin, tree planting to family planning, numerous campaigns have been implemented by the government since independence to instill what it deemed as desirable attitudes and behaviours. Little wonder, then, that campaigns have become a way of life for Singaporeans.

Over the last five decades, Singapore has conducted many campaigns covering a wide range of topics. For instance, there were campaigns to encourage the population to keep Singapore clean, take family planning measures, be courteous, raise productivity in the workplace and speak Mandarin as well as good English. There were also others that reminded the people not to litter, be a good neighbour, live a healthy lifestyle and even to wash their hands properly. Collectively, the purpose of these campaigns was to instill certain social behaviours and attitudes that were considered by the government to be beneficial to both the individual and the community. They were also used by the state as an instrument for policy implementation.1

Each of the campaigns introduced usually followed a three-stage implementation process. First, a social problem was identified by the government before a decision to rectify the problem through a nationwide campaign was made. Second, the campaign, together with its rationale and goals, was revealed in a public event. Third, a media blitz was launched to raise public awareness of the campaign. At the same time, a system of incentives and disincentives was also introduced to persuade the people to adopt the attitudes and behaviours promoted by the campaign.2

Campaigns in the Early Years of Nationhood

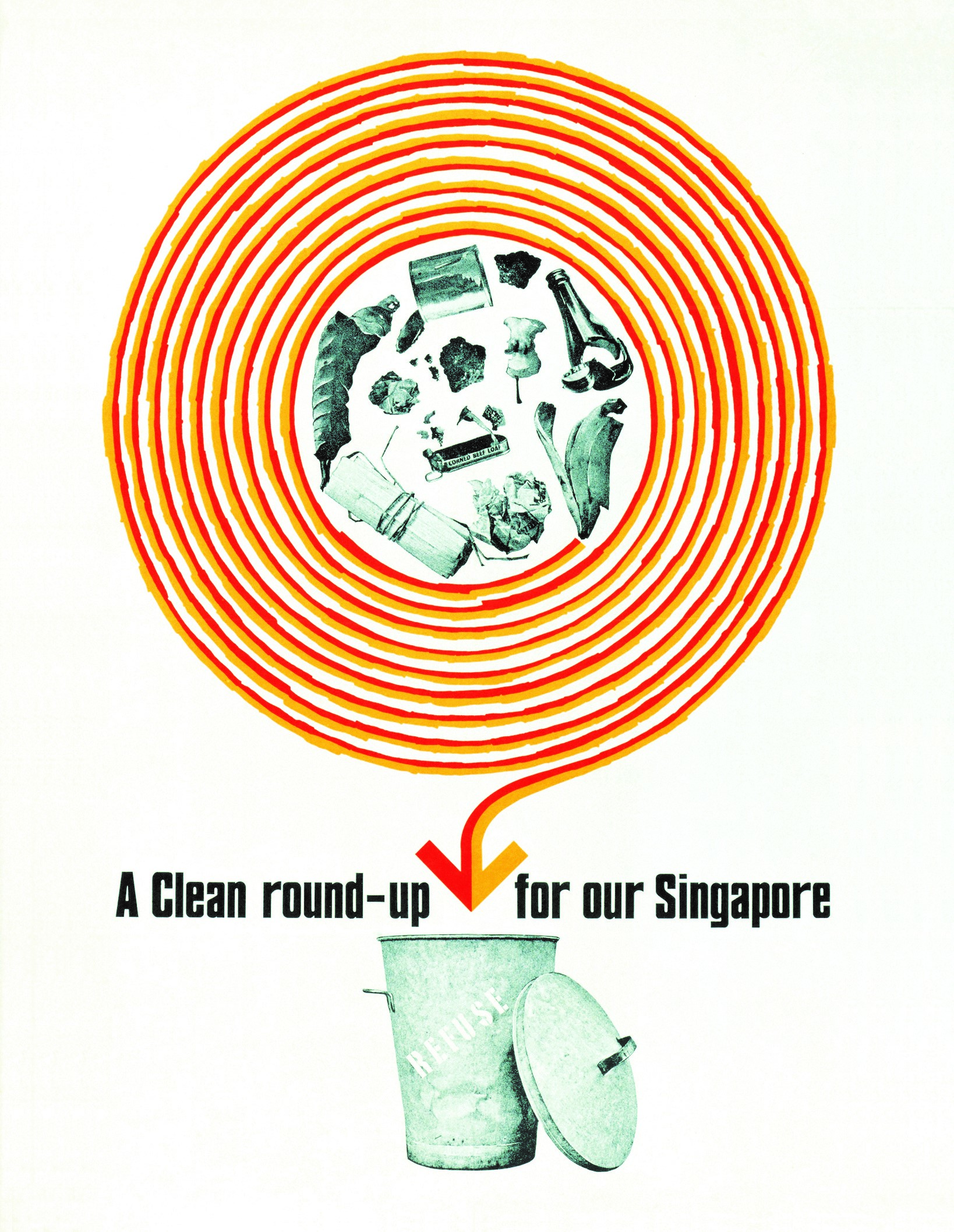

Most of the campaigns conducted in the early years after independence were designed to lay the foundation of a new nation.3 For example, the “Keep Singapore Clean” and “Tree Planting” campaigns launched in 1968 and 1971 respectively were to establish Singapore as a country that was clean and full of greenery. In fact, the two campaigns as well as other similar campaigns were part of a larger plan that included changes in public health laws, relocation and licensing of itinerant hawkers, the development of proper sewage systems and better disease control measures, and the creation of parks and gardens. The government believed that improving the environmental conditions of Singapore would enhance the quality of life of the population and cultivate national pride. It would also paint a better image of Singapore for foreign investors and tourists.4

Family planning was another major focus for campaigns in the late 1960s and 1970s. With slogans such as “Small Family: Brighter Future” and “The Second Can Wait”, these campaigns recommended the setting up of small families.5 Initially, the campaigns did not dictate the ideal family size. But with the launch of the “Two Is Enough” campaigns in the early 1970s, a two-child family norm was endorsed.6 The family planning campaigns came at a time when the government was faced with the formidable cost of providing education, health services and housing to a population that was growing rapidly due to the postwar boom. Family planning was thus regarded as a necessary measure for the government to slow the country’s birth rate.7 Furthermore, the government also rationalised that smaller families helped reduce financial expenditure in households.8

Campaigns of the 1980s and 1990s

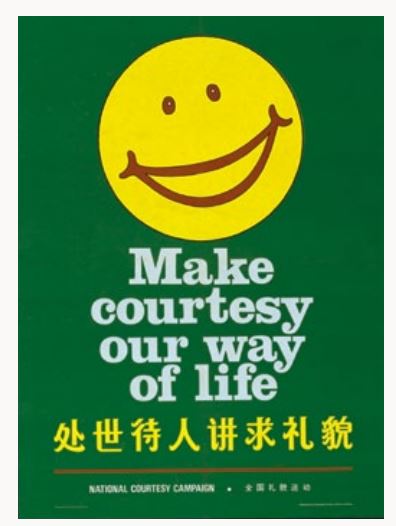

As Singapore society became more affluent in the 1980s and 1990s, improving the qualitative values of Singaporeans became the focal point of campaigns. Leading this was the National Courtesy Campaign. Inaugurated in 1979, the campaign aimed to create a pleasant social environment where people were cultured, considerate and thoughtful of each other’s needs.9 The campaign was initially represented by a smiley logo, with the slogan “Make Courtesy Our Way of Life”. This was subsequently replaced by the mascot known as Singa the Courtesy Lion in 1982.10

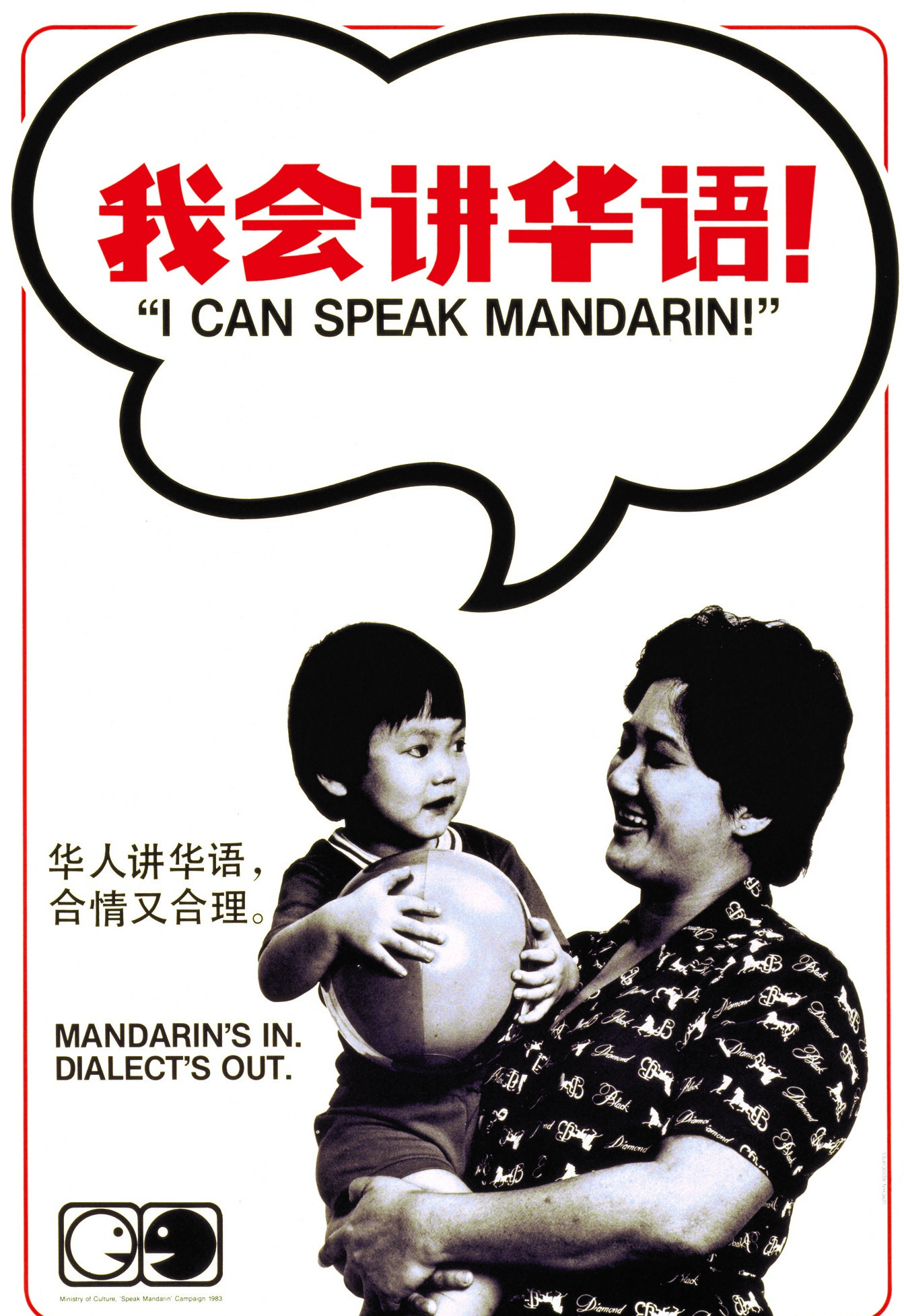

The Speak Mandarin Campaign was another campaign introduced to develop better qualitative skills for Singaporeans, particularly communication skills among Chinese Singaporeans.11 When the campaign was launched in 1979, it was believed that the use of dialects was hampering the bilingual educational policy for the Chinese in Singapore. As a result, the government felt that there was a need to simplify the language environment of the Chinese by encouraging them to speak Mandarin in place of dialects. The government also held the view that a strong Mandarin-speaking environment would help the Chinese better appreciate their culture and heritage.

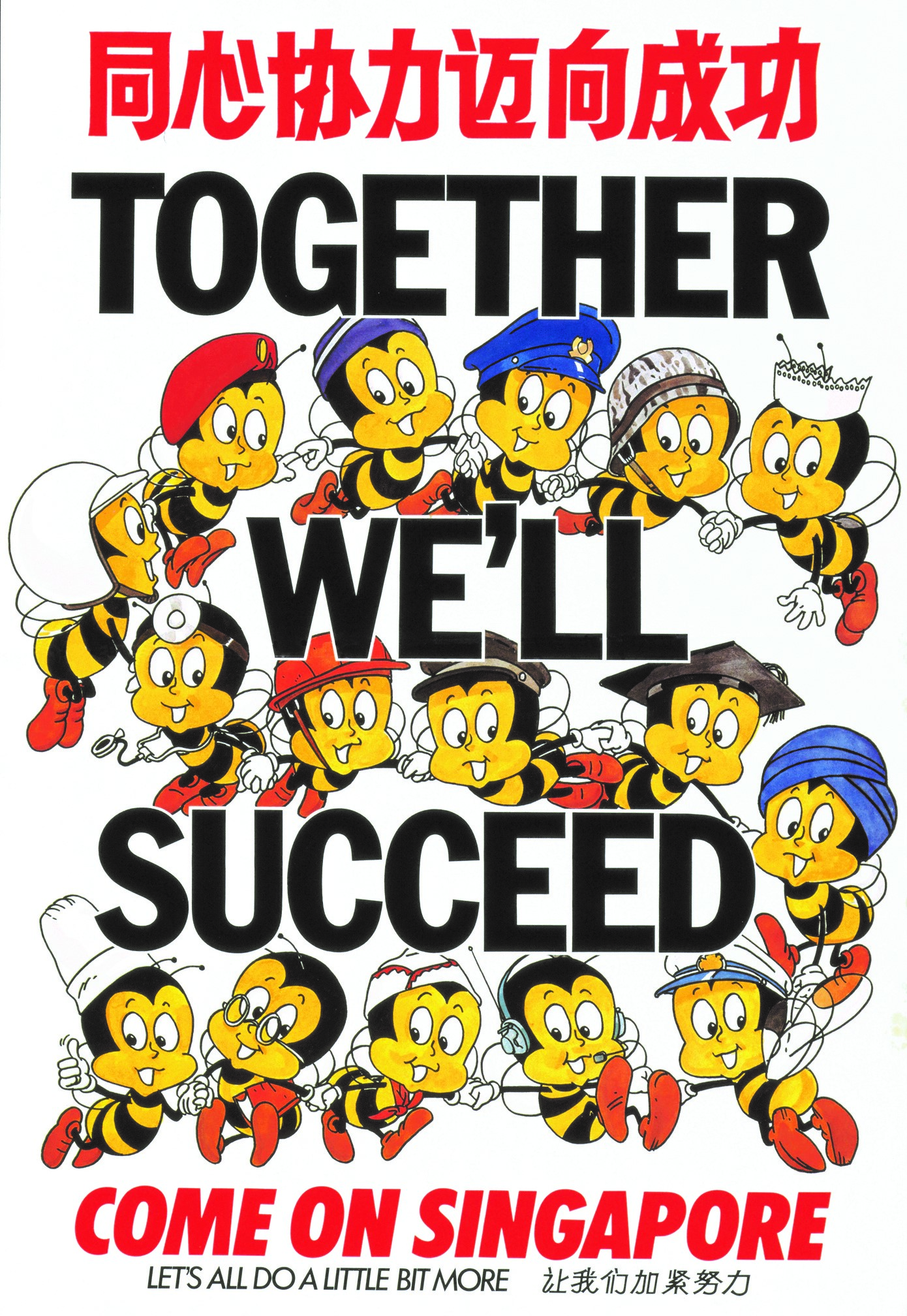

To improve the qualitative skills of Singaporeans in the workplace, the government launched the National Productivity Movement in 1982. Fronted by Teamy the Productivity Bee mascot, the campaign aimed to raise the productivity of the labour force. The campaign was endorsed as Singapore moved from labour-intensive activities to more highly skilled and technology-driven work. The campaign had a positive effect on the workforce’s productivity level. Between 1981 and 1990, Singapore’s productivity growth increased by 4.8 percent; since then, its workforce has been assessed to be one of the best in the world.12

Past Campaign Promotion Strategies

Campaigns in Singapore were promoted in many ways. The most common were posters and brochures as well as the distribution of souvenirs like bookmarks and collar pins. An array of channels such as mass media broadcasts, forums and talks were also used to raise the public’s awareness of the campaigns.13 From the 1980s onwards, some of the campaigns such as the National Courtesy Campaign began using catchy slogans and jingles to get the message out.14 They also started using TV commercials, sitcoms, school activities and competitions to help raise awareness. Extra measures were also taken to ensure the campaigns’ efficacy. For instance, when the Speak Mandarin Campaign was launched, dialect programmes over the radio and television were phased out gradually and Chinese civil servants were asked to set an example by refraining from using dialects during office hours.15

Using the civil service to set good examples was another strategy that was frequently used by the government in promoting campaigns.16 When the National Productivity Movement was introduced, the civil service was roped in to set the standard for others to follow by launching the Civil Service Computerisation Programme. The focus of the programme was to improve the functions of public administration through the effective use of information technology products. This involved automating work functions and reducing paperwork for greater internal operational efficiency.17 Other than embarking on a computerisation programme, the civil service also started adopting quality control standards to improve work attitudes, motivation, productivity, team spirit and service standards of civil servants.18

Campaigns Today

Throughout the rest of the 1990s and the first decade of the new millennium, the government continued to use campaigns to communicate with the population. The many campaigns that were introduced during this period included the “Great Singapore Workout” in 1993, the “Speak Good English Movement” in 2000 and the “Romancing Singapore” campaign in 2003.19 As the frequency of campaigns grew, it was felt that Singaporeans were slowly becoming immune to the messages conveyed by the campaigns.20

Indeed, in almost every part of the island today, be it in a park, food court, building or any other public space, there is a high chance that a person will come across posters, banners, stickers or other collaterals promoting one campaign or another. With the advent of social media tools such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and mobile apps, it is common for Singaporeans to come across campaigns on these platforms.

In order to preserve and maintain the relevance of campaigns, the government has started taking steps to revise the way campaigns are conducted.21 For instance, many of the older campaigns have been consolidated into larger ones to reduce the number of campaigns run annually. Furthermore, the private sector was encouraged to initiate and front some of the newer and existing campaigns. This was to give campaigns a less top-down approach, making them less intrusive and more judicious to the public. Even with these changes, it is certain that campaigns will continue to be an integral part of the social fabric of Singapore society, thus making campaigns truly a way of life for Singaporeans.

Looking at Singapore through its various campaigns is an interesting way to track the growth and evolution of the nation from its nation-building, post-independence years to the modern society it is today. The campaigns are a way through which we can discern the concerns and responses of the government to issues facing the Singapore society at large.

Singapore’s campaign and their mascots have become an idiosyncratic and often nostalgic part of our national heritage. No other country has embraced campaigning as much as we have. To highlight this slice of Singapore identity, the National Library of Singapore, in partnership with independent art curator, Alan Oei, presents the exhibition, “Campaign City: Life In Posters”, now ongoing at the National Library Building.

“Campaign City: Life in Posters” features 40 of Singapore’s leading artists, architects and designers and 10 local art students. The participants, drawing inspiration and information from the National Library’s and National Archives’ vast collection of campaign posters and campaign heritage material, created artworks reflective of their own personal memories and/or impressions of Singapore’s campaigns, past and present. These artworks are on display along with highlights from the library’s campaign poster collection. Selected spaces in the National Library Building have been used in novel ways to convey the rich histories behind Singapore’s campaigns. The exhibition runs from 9 January to 7 July 2013 at Level 11 of the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library in the National Library Building.

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. He has co-edited two books Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He is currently conducting research on the Eurasian community for an upcoming National Library exhibition.

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. He has co-edited two books Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He is currently conducting research on the Eurasian community for an upcoming National Library exhibition.

NOTES

-

Sandhu, K.S. & Wheatley, P. (1989). Management of success: The moulding of modern Singapore (p. 116). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 MAN) ↩

-

Langford, J.W. & Brownsey, K.L. (1988). The changing shape of government in the Asia-Pacific region (pp. 134–135). Halifax, N.S.: Institute for Research on Public Policy. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Pan, H. (2005). National campaigns: A way of life (p. 104). In Legacy of Singapore: 40th anniversary commemorative 1965–2005. Singapore: CR Media. (Call no.: RSING q959.57 LEG) ↩

-

Sam, J. (1968, October 2). ‘Big stick’ for unresponsive. The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture. (1972, July 20). Speech by Mr Chua Sian Chin Minister for Health at the opening ceremony of the Family Planning Campaign 1972 at the Singapore Conference Hall on Thursday, 20th July 1972 at 2000 hours. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Singapore Family Planning and Population Board. (1973). Seventh annual report of the Singapore Family Planning and Population Board 1972 (p. 44). Singapore: Singapore Family Planning & Population Board. (Call no.: RCLOS 301.426 SFPPBA) ↩

-

Family planning in Singapore (pp. 1–26). (1966). Singapore: G.P.O. (Call no.: RSING 363.96095957 FAM) ↩

-

Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts. (2009, August 18). National Campaigns. Retrieved from MICA website. ↩

-

Nirmala, M. (1999). Courtesy – More than a smile. Singapore: The Singapore Courtesy Council. (Call no.: RSING 395.095957 NIR) ↩

-

Lee, P. (1982, May 15). Mascot for campaign. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lee to launch ‘use Mandarin’ campaign. (1979, September 7). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wong, M. (2010, February 2). Singapore’s productivity drive started in the 1980s. Channel NewsAsia. Retrieved from Channel NewsAsia website. ↩

-

Promote Mandarin Council. (2020, December 1). History and background. Retrieved from Singapore Mandarin Council. ↩

-

Singapore. National Productivity Board. (1991). The first 10 years of the productivity movement in Singapore: A review. Singapore: National Productivity Board. (Call no.: RSING 338.06095957 FIR) ↩

-

Singapore. National Computer Board. (1986). Civil service computerisation programme: Charting new directions. Singapore: The Board. (Call no.: RSING 354.5957000285 CIV) ↩

-

Raj, C. (1981, July 29). The civil service may implement QC circles soon. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Life in Campaign City. (2007, July). Challenge. Singapore: PS21 Quality Service Committee, Prime Minister’s Office. (Call no.: RSING 354.595700147 C) ↩

-

Sandhu & Wheatley, 1989, p. 116. ↩