Some Thoughts on the Theme of Death

Family and friends have long had to bear with my vocal thoughts on endless scenes of wasted death on the news. My emotive views come from what I assumed were my limitless powers of empathy. As I have read and watched the news from the comfort of a warm home in a peaceful Singapore, I thought I fully understood the pain of a husband weeping over a wife killed by crossfire or a grieving mother whose child lay limp due to famine caused by man’s disregard for fellowman. My self-delusion ended only recently.

About four months ago, my wife chanced on a book in Bishan Public Library. It was Sebastian Barry’s On Canaan’s Side: A Novel (2011). I remember it well as it helped me acknowledge my inadequate empathy. I actually wrote down parts of the first chapter called “First Day without Bill”, lest I forget:

So when asked to write on the theme of death, I found myself turning to other writings that ponder mortality and loss, remember loved ones, memorialise those who have led inspiring lives; or think of events that have moved us. I looked first to books on my shelves at home.

Since my younger days, a favourite has been Totto-Chan: The Little Girl at the Window (1981) by Tesuko Kuroyanagi (translated by Dorothy Britton, 1982). In this book brimming with enhancement, there is a moment’s pause as we experience a first meeting with death for a little girl:

Totto-Chan suffers an unexpected loss and reflects quietly in a straightforward and unencumbered way. Her loss is at once real and, in relation to so many different everyday things, final.

In Shadowlands: The Story of CS Lewis and Joy Davidman (1985) by Brian Shelby, we find a fascinating perspective on the fear of death – an almost selfish but a very human one:

I also recall E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web (1952) where Charlotte summons all her strength to wave a final goodbye to her dear friend Wilbur:

Charlotte’s lonesome death is at once tinged with sadness. Perhaps it is offensive to some instinctive humanity that knows it is wrong for one to die so alone at the end of life’s journey.

On dying alone, I have found some harrowing stories in the oral history collection of the National Archives of Singapore. Sew Teng Kok recalls the death houses at Sago Lane:

Some might lament that the younger generation has forgotten filial piety and the community spirit of the “good old days”, but this account is one reminder that there are actually many things that are best left in the past.

The collection of oral history recordings on the Japanese Occupation reveals a particularly painful chapter in our history. Three hundred and sixty one powerful interviews fill gaps left by the deliberate destruction of official records by the Japanese administration and capture the recollections of all the communities and peoples caught up in this brutal period of our history. Ng Seng Yong, who was held along with residents from Geylang, Joo Chiat and Telok Kurau, recalled the randomness with which death visited:

The penghulu (chief) of Punggol Village, Awang bin Osman, recalled the aftermath of one such massacre:

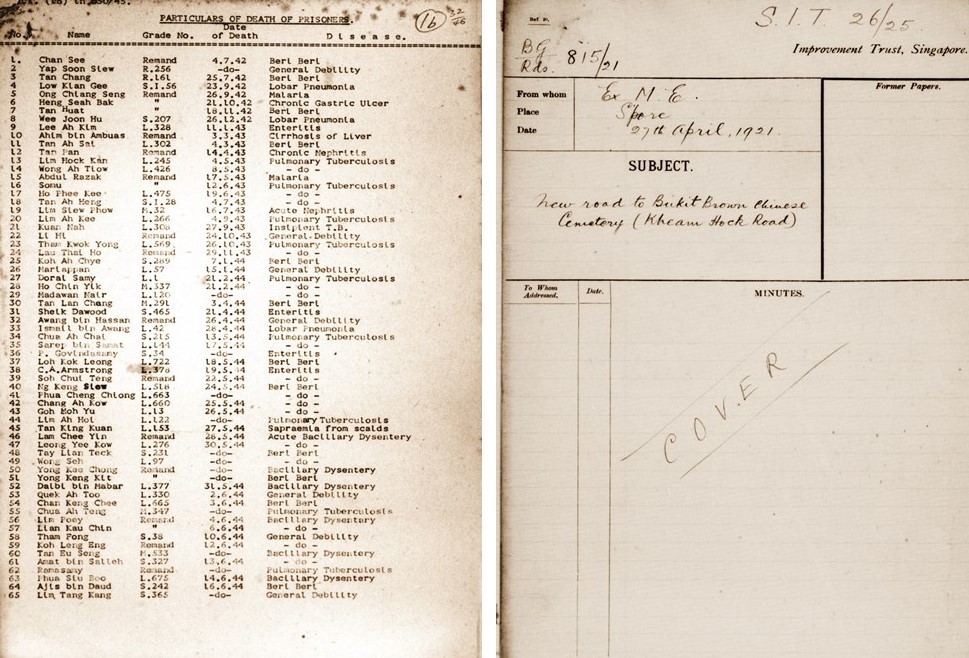

In my search for records on death, archivists at the National Archives pointed me to one of the few written records of death during the Japanese Occupation that had been secretly kept by the chief record clerk, Benjamin Cheah Hoi, and the medical officer, Dr Lee Kek Soon. As stated by the Superintendent of Prisons in a memo dated 26 September 1945 to the British Military Administration:

The so-called “diseases” set out in the prison records tell a horrific tale of hardship and neglect as “Beri Beri” and “Bacillary Dysentary” became the main emissaries of death for Chinese, Malays, Indians and other races in prison.

Singapore has, however, been blessed with more peace than many a country and we have largely been able to bury our loved ones with reasonable dignity in relatively tranquil surroundings. A number of records in the Archives dating from the time of Raffles reveals that the search for suitable burial grounds also occupied the highest offices during Singapore’s early days as a colony. This is shown in a letter of February 1823 from William Farquhar, the first resident of Singapore. He conveyed the view of the Lieutenant-Governor that “the present European Burial Ground” was “objectionable” and there was a need to “select a more suitable spot at the back of the Government Hill” (now Fort Canning).

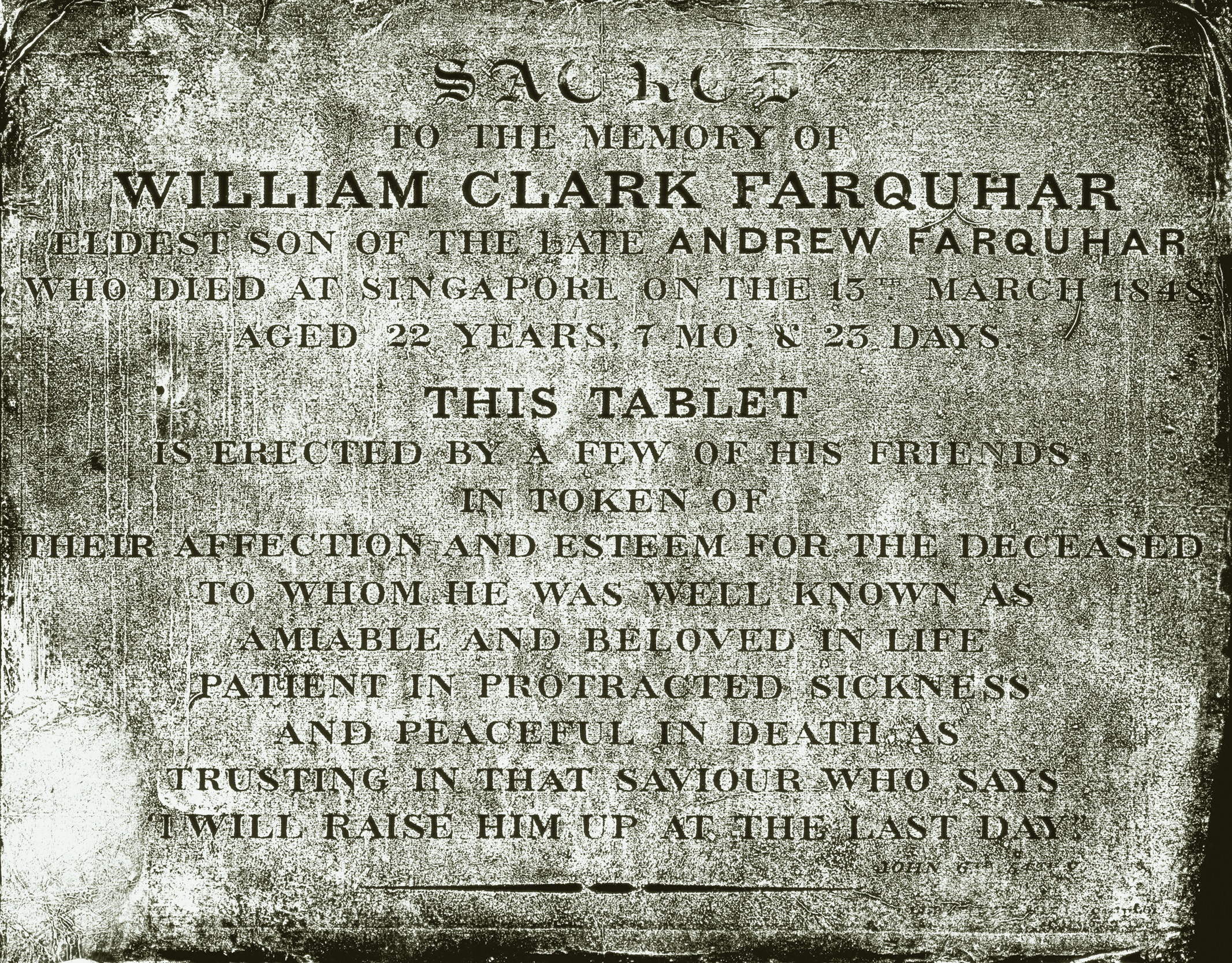

The image collection of the Archives contains, among many other things, pictures of stone rubbings of some of the earliest memorial plaques from the early Singapore cemetery at Fort Canning. The images from Fort Canning will, of course, be a reminder of a colonial past with names that are associated with our beginnings. There are epitaphs, among others, to Stephen Hallpike, who is said to have founded the first shipyard in Singapore, and William Clark Farquhar, the great-grandson of William Farquhar. These epitaphs do not simply record the dates of deaths but attempt to give us an enduring insight into these men as individuals, lending them some humanity.

Images of such epitaphs reminded me of a very short epitaph with deep meaning that I came across when reading The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien (edited by Humphrey Carpenter with the assistance of Christopher Tolkien, 1981). Tolkien’s epitaph to his wife was, in a sense, a riddle as he was so wont to write. His letters, however, give an insight to an undimmed and cherished memory of young love. In a letter to Christopher Tolkien on 11 July 1972:

Browsing the shelves of the Singapore collection in the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library, a recent publication caught my eye – lovingly written and put together through the perseverance of the Singapore Heritage Society – Spaces of the Dead: A Case From the Living (edited by Kevin Y.L. Tan, 2011). Looking through the bibliography, Chapter 8 of Brenda S.A. Yeoh’s Contesting Space: Power Relations and the Urban Environment in Colonial Singapore (1996) stood out to me and it was a fascinating read. It is superbly researched and tells the surprisingly interesting story of controls and conflicts over burial grounds in colonial Singapore. To echo Spaces of the Dead: there “are a surprising number of books and articles on Singapore cemeteries” – and I am especially heartened to see books lending interpretation and giving life to archival materials.

I have also had the opportunity to delve into records relating to burial registers, cemeteries, burial grounds and related rites. I read with fascination the debates of proceedings as the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements finally managed to assuage Chinese opposition and passed a Burials Ordinance in 1896. Dr Lim Boon Keng was a local representative on the Legislative Council, and two things that he said resonated with me. The first was his personal view that the Chinese select their graves through the “observations of a geomancer” according to a system that he himself candidly regarded as “superstition”. The second was his response to the concerns of the governor that “the most beautiful spots in the Colony might be destroyed for the whim of a Chinaman”. In an eloquent retort, Dr Lim emphasised that the “feelings of Chinese towards their deceased relatives” was a strongly held one:

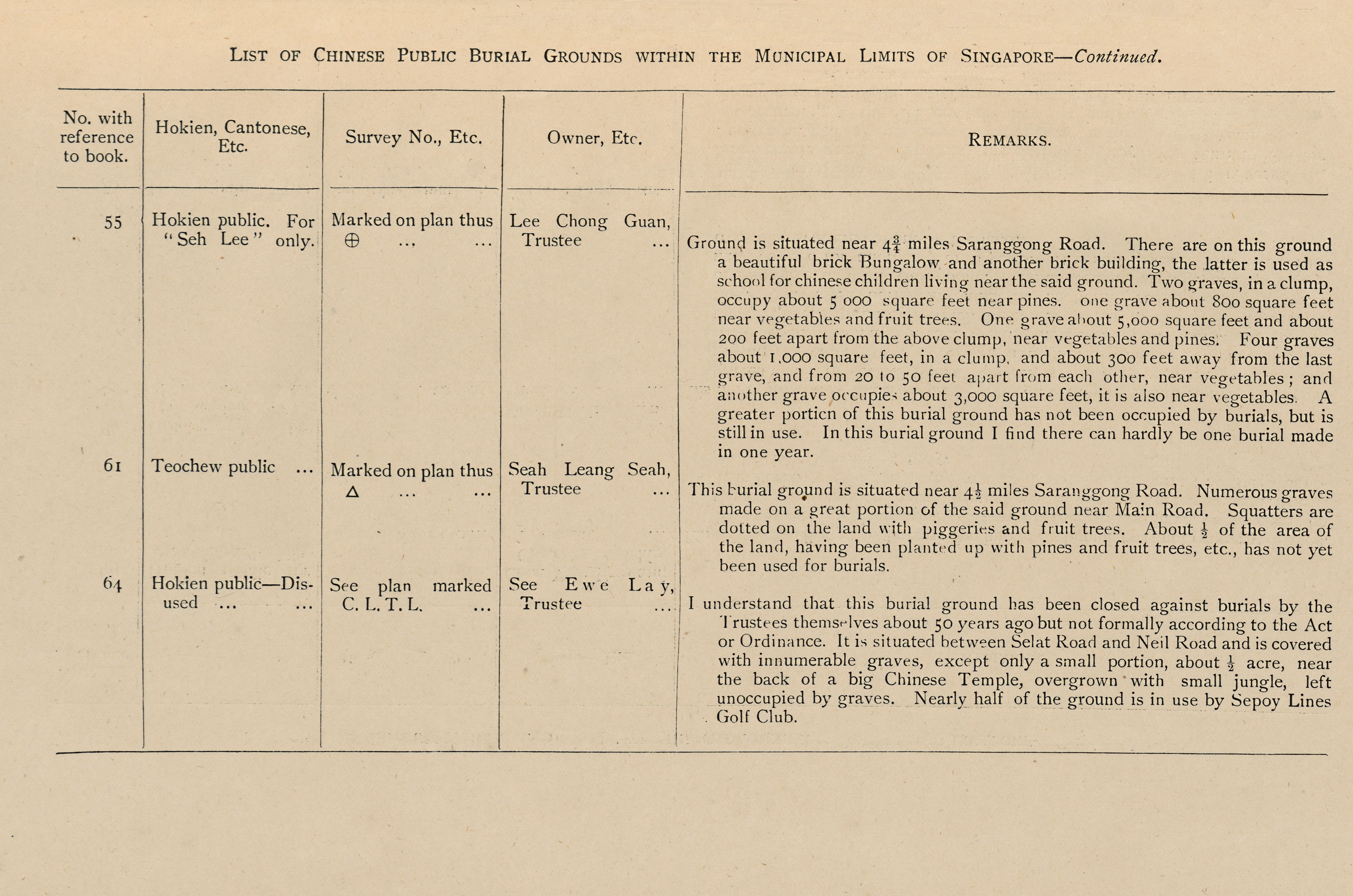

Another excellent example of a record that sheds light on Singapore’s early days is the 20 February 1905 Report of the Burials Committee appointed by the Governor. From this one record, there are at least four diverting lines of inquiry for the intrepid researcher/historian. The first was the attempt to use access to limited cemetery plots as a reward for “services” or a potential tool of control. There was a recommendation strongly put forth and accepted by the Colonial Secretary that “the privilege of burial [within the Municipal Limits] be granted only in the case of Chinese who in the opinion of the Governor in Council have rendered eminent service to the Colony”.

The second was that there was a need then for cemeteries for the Chinese to have “suitable arrangements” for the separation of clans. The third was that many of the cemeteries had other uses apart from burials – perhaps early evidence of a practical side of Singapore taking shape or the inevitability of the need to balance the needs of the living and the dead within land-scarce Singapore. As reported in the case of a burial ground “situated near 4½ miles Saranggong Road”, a good many burial grounds housed not just the dead but also squatters, “piggeries” and were sites for the cultivation of fruit trees. And finally, for those who mistakenly believe that the passion for golf was a recent development and the result of country clubs sprouting in modern Singapore, it was reported that a Hokkien burial ground “situated between Selat Road and Neil Road… is covered in innumerable graves” and “[n]early half the ground is in use by Sepoy Lines Golf Club”.

Despite these valiant early attempts to control and manage the conduct of burials, there is evidence that a rather cavalier attitude continued apace for some time yet. One particular exchange recorded in Municipal Office files from 1924 on a “Hokkien Burial Ground Alexandra Road” stood out for me. With the distance of time, it now makes for somewhat amusing reading:

In more recent times, the Bukit Brown Cemetery has, of course, dominated the conversation on burial grounds. To me, a key legacy of Bukit Brown is that it marked one of the significant steps in the journey towards a common Singaporean outlook as it was the first Chinese municipal cemetery open to all regardless of clan associations or other affiliations. There is a certain irony but an archival record uncovered from the “Improvement Trust, Singapore” files from 1921 appears to be a small microcosm of the Bukit Brown conversations of today. The file named “New Road to Bukit Brown Chinese Cemetery (Kheam Hock Road)” showed that in order for Kheam Hock Road to be built to provide better access to Bukit Brown for the common good, some 40 graves had to make way for the development.

What the 40 graves looked like and what stories they could have told, and who were affected (dead or living), are unknown. A major difference today is the extent of documentation that can and will be achieved. There is now a Bukit Brown Cemetery documentation project that is being undertaken with great enthusiasm and passion by a highly professional team supported by the Urban Redevelopment Authority and the Land Transport Authority. The Bukit Brown Cemetery documentation, including photographs and videos of graves, exhumations and related religious rites will in time become part of the public records kept by the Archives. These epitaphs and other stories of lives lived will, in time, be gently unfolded and researched as many now increasingly seek to uncover our roots in Singapore.

It can be noted that these newer records will contain a lot more in the form of born-digital audiovisual records. Audiovisual records were not so readily available in the past but those that the Archives has preserved relating to death range from official footage of state funerals of past presidents to Berita Singapura broadcasts of Qing Ming festivals past. Other records include broadcast footage of disasters such as the collapse of Hotel New World. In an indication of the significance of cemeteries in our lives, the Archives has also produced its own video documentation of the Bidadari and Bukit Brown cemeteries.

In this context of our increasing ability to easily make records of ourselves and our loved ones, John Miksic’s thoughtful final reflections in his chapter, “Fort Canning: An Early Singapore Cemetery”, from Spaces of the Dead are apt. He reflects on how attitudes have changed such that the “need to have large monuments at which to remember the dead, to meditate on them, and to contemplate one’s own possible demise so as to be prepared both financially and emotionally, has evaporated”.

Other similar shifts in attitudes have been observed for a time. Among many insightful writings in her Bamboo Green (1982) series of articles, Li Lienfung wrote of the struggles faced in mourning the death of her mother, who was not religious and though “a woman born of the last century”, had left a legacy of breaking “away from… tradition”:

Li’s views on long-held practices are strongly put and might bring reproach in some quarters, but she captured the growing clash of wishes over religious affiliations and the relevance of traditions that I myself have witnessed between different generations.

Death has occupied man for as long as we have been aware of the inevitability of the end for ourselves and our loved ones. I have but made a short exploration in the space given to me.

I have found that the NAS has been a steadfast keeper of enduring facts, evidence and memories through its collections of documents, images, oral history recordings and audiovisual records. In the traces that death leaves behind, through headstones, burial registers and other records, we are brought on a journey that can give us context and insight into times past and how certain things came to be – with twists and turns into diverse fields including colonial politics, war and its atrocities and the land use policies of a land-scarce country.

While archival materials shed light on certain conditions of the past, it is literature and other writings that bring sometimes disparate threads together and lend broader perspectives and humanity to a subject that we cannot ignore.

I give the final word to the spiritual writings of Kahlil Gibran. In The Prophet (1926), he speaks of death as a glorious triumph and this resonates with those who desire a closeness with God. Yet, I believe that it has a potent universality as it is also able to stand alongside the staunchly scientific, who may question the existence of God and hypothesise that humans are “starstuff ” that has “grown to self-awareness” (Cosmos by Carl Sagan (1980). Regardless of our belief (or not) in a God, the cosmos nevertheless reclaims us in time: