Oriental, Utai, Mexican: The Story of the Singapore Jewish Community

Inscribed in the urban landscape of Singapore, through buildings such as the David Elias Building and the Abdullah Shooker Welfare Home, is the story of an oft-overlooked group in Singapore’s history: the Jewish community.

According to one story, the name Jurong was inspired by local Jewish magnate, Joe David, whose relative operated an open-air cinema in the area after World War II. David was commonly identified as “Orang Jew” (Jewish man), a name that morphed into “Jew-Orang”, and then shortened to “Jurong”.1 This urban legend may be patently untrue, but it remains a romantic and telling story.2 The fable shows the small Jewish community’s outsized cultural, political and mercantile contributions to Singapore since the early 19th century, and yet how distinctly their ethnicity has always set them apart in Singaporeans’ minds.

A Rich Homogeneity in Opium

In 1830, the first census of Singapore recorded “[n]ine traders of the Jewish faith”, all male, living in a British colony of over 16,500 residents.3 In all likelihood, they were Baghdadi Jews, also known as Sephardis, who had arrived from Iraq via Calcutta. Part of the Baghdadi trade diaspora, these pioneers constituted a handful of the many Jewish merchants who, from the late 18th century, escaped Ottoman governor Daud Pasha’s persecution to trade in the British East India Company’s far-flung outposts.4

Buoyed by Singapore’s new status as the Straits Settlements capital, these Jewish founding fathers thrived from the legalised opium trade, a majority of its revenue going towards Singapore’s operation.5 From their godowns at Boat Quay and Collyer Quay, they sent Indian opium onwards to Hong Kong and Shanghai.6

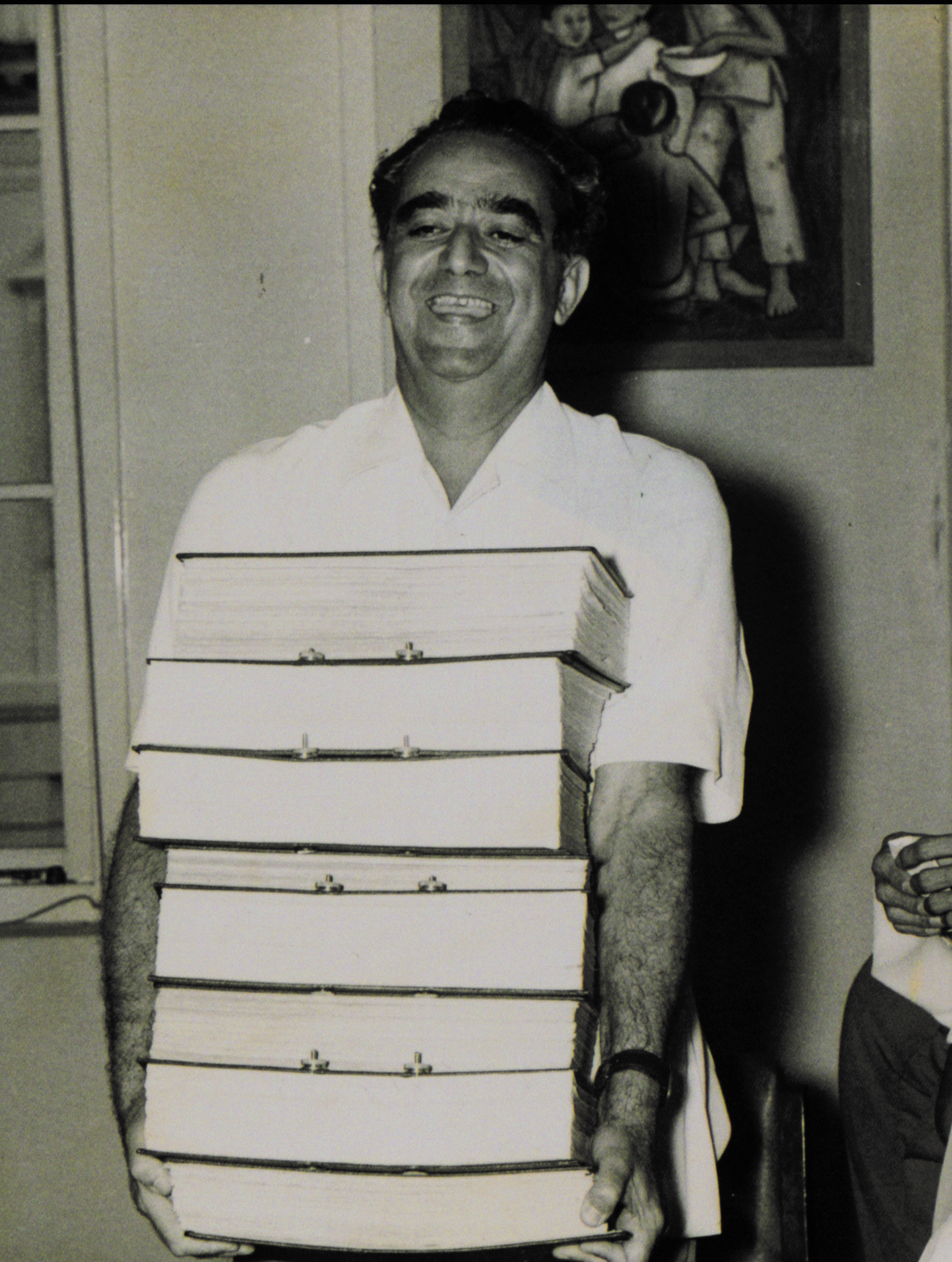

Community historian Eze Nathan’s The History of Jews in Singapore provides an important portal into their lives. Like his father, they initially spoke Arabic or Hindustani and wrote in Hebrew. Their style of dress was Arabic, they smoked the hookah (a tobacco pipe), and without formal accountancy training, wrote business accounts on their shirt cuffs.7

Even by then, Singapore was already a multi-ethnic entrepot, hosting Malays, Armenians, Parsees, Arabs and Chinese dialect groups, amongst others.8 To almost all these immigrants, Singapore was a mere commercial stopover. Jacob Tomlin, an English Christian missionary who encountered the Jewish people in 1830, found them “well acquainted with their own scriptures and… [referring] to the approaching restoration to their own land”.9

Their return home to India was to be delayed, for by 1840 the Sassoon family, a pillar of the opium trade, had set up shop in Singapore.10 Perhaps due to their influence, 1841 was to be a landmark year for the nascent Singapore Jewish community: a synagogue and cemetery were built for its 22 residents, including the first four women.11

Following a petition, the governor allowed three trustees with the surnames of Cohen, Ezekiel and Ezra to lease a plot of land to use for worship. Located in a shophouse on what became known as Synagogue Street, Singapore’s first synagogue was a decidedly humble affair. In 1858, visiting Israeli poet Jacob Sappir12 reported that the Orthodox synagogue “gathered cobwebs”, as a minyan (quorum of 10 Jewish men) assembled only on some Sabbaths.13

The trustees were also awarded a 99-year lease for the first Jewish cemetery. Located at today’s Dhoby Ghaut MRT, the Orchard Road Cemetery, or Old Cemetery, was moulded out of “a very swampy area… on the very fringe of the jungle”.14 It was to remain there until 1983 when the government repossessed it.

With these two places, the community moved from “traders” to “settlers” of Singapore in the census and, more importantly, in their self-identities. As pioneering “port Jews”,15 they did not have to confront the choice that faced the second generation: “adapt to the British-dominated world and succeed financially, or maintain the life they had at home”, as Joan Bieder frames it in her authoritative The Jews of Singapore. 16

One such person who straddled both worlds with panache was Abraham Solomon (1798–1884). Like David Sassoon in Bombay, Solomon became wealthy through opium, and served as Singapore’s Nasi, the unofficial Jewish community leader.

He led a British lifestyle, living away from the commercial centre in a large villa, where he once entertained surveyor John Turnbull Thomson.17 Simultaneously, he was a strict Orthodox Jew, refusing to eat with a goy (gentile) as it was not kosher (observant of Jewish food laws).18

However naturalised Jewish persons like Solomon became in cosmopolitan Singapore, they stood irrevocably apart in the name of the law. “[T]he Singapore Jews became thoroughly anglicised,” anthropologist Tudor Parfitt notes, “[but] the majority of Jews were always regarded as Orientals or Asiatics.”19 Nathan adds that, from young, he was made aware of this label: “a tone of disparagement was easily detectable” in its use.20 Even the official recognition of their places, but not persons,21 Jewish people were banned from British institutions like the Tanglin Club, and more pertinently, the British Army, where their attempts to fight for their adopted country in the two world wars were rejected.

Despite this seeming hypocrisy, the Jewish community had a pressing reason to stay: money. Historian C.M. Turnbull records that, by 1846, the six Jewish merchant houses outnumbered Chinese-operated ones, and were second only to the British. As a guarantee against the unstable opium trade, Jewish merchants had by now diversified their booming business, importing and exporting goods like coffee and timber, and moving into the stock market.22

Slowly, Singapore began to become theirs too, even as their thoughts turned to their ancestral villages. Like the early Chinese immigrant experience about which poet Boey Kim Cheng wrote, the Jewish community was to “discover how transit has a way of lasting, the way these Chinatowns / grew out of not knowing to return or to stay, and then became home”.23

Open the Flourishing Floodgates

In 1869, the Suez Canal opened, letting in a diverse Jewish community to Singapore: rich, middle-class and poor, Sephardis and Ashkenazis, all of whom carved out their own enclaves. This second generation of Singapore Jews ushered in the golden years: in 1872, the Jewish population was 172-strong and mostly Baghdadi; by 1942, there were nearly 2,000 diverse Jewish people, the height of the Jewish population.24

For some, fortunes in both senses redoubled. Manasseh Meyer, a first-generation Sephardic Jew, arrived early enough to take full advantage of the 1875 law awarding “aliens” like him “equal rights with the British” in property, and later the tin and rubber boom.25 By 1900, he owned three-quarters of Singapore, making him the “richest Jew in the Far East” and the natural inheritor of Solomon’s Nasi role.26 He also established homes at Sophia Road, Katong and Bencoolen Street.27

For others, migration was simply not what it used to be. Hearing tales of their rich brethren, large numbers of impoverished Baghdadi Jews began making the shorter trip to Singapore. They moved into the Mahallah, where most of the Jewish community now lived, and where “the gap between the rich and the poor was complete and dramatic”. These new Sephardis were clerks, peddlars of the traditional Baghdadi roti, or wholesale traders – a far cry from being landlords and opium barons. Nathan recalls passing the Mahallah houses, the poorest on Short Street, where “rooms were often almost bare of furniture”.28

The Suez Canal also opened doors to another distinct breed of Jewish people: the Ashkenazis, or “white Jews”. As with the Baghdadis, the Ashkenazis were fleeing anti-Semitism, this time from the pogroms in Poland and Russia.29

As compared to the Baghdadis, these European Jews, who looked more German than Arabic, were even more rooted in their country of origin. They sent their children “home” for school, unlike the Baghdadis, who were enrolling their children in local colonial institutions.30 And although they attended the same synagogue, they kept to themselves even after death – until 1939, Ashkenazis were buried in different sections of the Orchard Road Cemetery.31

This new stratification in Jewish society also occurred within groups. Among the Baghdadi Jews, a rift was developing between the rich, English-speaking elites, such as Meyer and Joseph Elias, and the poor, Arabic-speaking migrants of the second wave.32

In 1873, Meyer began planning a new synagogue to cater for the burgeoning population. The Maghain Aboth, a simple one-storey building, was consecrated in 1878 on Waterloo Street, with a second storey later added. But the widening language and class divide followed him there. In the synagogue, there was a literal segregation among three groups: the wealthy sat on the left of the bimah (dais), shopkeepers and small merchants on the right, and the poor behind.33

Arguments began to arise among the synagogue’s members about religious rituals and the order of service.34 To escape the rancour, Meyer simply built his own synagogue – Chesed-El – and brought in a personal Hazan (minister) from Baghdad. The imposing Chesed-El, incorporating Roman and Greek architecture, opened in 1905, but its distant location on Oxley Rise made it inaccessible to the Mahallah’s poor.35

In retrospect, these divisions in the once largely homogeneous Jewish community were inevitable. Besides the sudden population increase, the opium trade had been completely taken over by the British in 1910, denying newcomers a direct road to riches. All the same, the Cohens and Ballas are examples of prominent families who rose from extreme poverty, while the early 20th century was especially easy-going for middle-class Jewish people, even through the Depression. “We were all royalist,” Nathan recounts. “We were unaware of racial tension – were we not all British?”36

This simplistic self-conception was to be unsettled by World War I, when the Jewish status as Asian “left a scar on society”. Already denied access to the upper echelons of the civil service, these “Asians” were still so keen on volunteering to fight for the British Army that in 1914, H.J. Judah, a Sephardic Jew, sailed to England to enlist. He was granted a rare commission, and was subsequently killed in action.37

In response to the mass Jewish migration to Palestine in the 1920s, a nascent cultural connection to Zion began to replace the shaky British identity. This broader self-positioning was spurred by the 1921 and 1922 visits of Zionist leaders Israel Cohen and Albert Einstein, respectively.

Hosted and supported by Meyer, Cohen spoke about the 1917 Balfour Declaration, which supported a Jewish state in Palestine. He also established a Zionist Society in Singapore. The next year, another prominent visitor came appealing to Meyer for money. A week before he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, Albert Einstein pulled into the island on the Kitano Maru to much fanfare.38

In the audience was a 14-year-old boy named David Saul Marshall. Having been expelled from St Joseph’s Institution for missing class on Yom Kippur (the holiest Jewish holiday), Einstein’s speech, which appealed for the establishment of Jerusalem’s Hebrew University, must have struck a chord in the Sephardic Jew.39

As the first-born eldest son, Marshall parlayed this broader Jewish identity and push for social equality into ISRAELIGHT,40 a magazine he edited.41 He wrote in the editorial: “Our community is drawn from every part of the world… We should be able to build on these cultures.”42 It was a considered sentiment about the multi-ethnic nature of Singapore life that was to underpin his political philosophy43 as Singapore’s first chief minister.

Surviving as Utai

As historians Kevin Blackburn and Karl Hack argue, the Japanese Occupation was far from a unifying experience.44 During the Syonan years, the Japanese perpetuated the British strategy of “Divide and Rule”, meting out different treatments to each ethnic group. The Jewish community was marked out for humiliating punishment, but escaped the sufferings dealt to the Chinese.

Even after Hitler began to terrorise Europe in the 1930s, the local populace was lured into a sense of contentment by British propaganda. The Jewish community heard horrific stories from afar and boycotted German products. Nathan, Marshall and others in the community raised funds for German refugees to find work in Singapore and Malaya. Yet, as Nathan writes, “in Singapore, it all seemed remote. We were observers at a safe distance. The war had scarcely touched us”.45

It was only after the attack on Pearl Harbor and the bombings of Singapore in January 1942 that people started to collectively panic. In the Mahallah, a boy saw the milkman suddenly split in half by shrapnel.46

Once again, the Jewish community offered to help the British fight, and once again they were turned down because they were “Asian”. Marshall himself joined the Straits Settlements Volunteer Corps “partly to prove Jews were not afraid to fight”, and also because “he had been ashamed that during WWI, [some] Jewish men told the authorities that they would be happy to support the war financially, but the Torah forbade them to go into battle”.47

A mass exodus began in late January 1942. Jewish families who could afford tickets queued in long lines at shipping agents, desperate for any exit passes. They were not spared racial discrimination. Nathan’s sister, Dorothy, recalls an official withdrawing the family’s passes when the official spotted her dark-skinned brother. By the time Singapore fell to the Japanese, half of the Jewish population had fled, and most never returned. An estimated 250 sought refuge in Bombay, while others made it to Calcutta, Australia, Palestine, England and the United States.48

For the unlucky half who were too poor to leave, their time was marked by a bizarre ethnic prejudice. An order was issued in the only newspaper, Syonan Shimbun, that Jewish people were to report at Orchard Road Police Station, near the Old Cemetery. The next day, the estimated 700 Jewish people who turned up were issued a white armband with a red stripe in the middle. Written on it were their name, number, and the word Utai, Japanese for “Jew”. They had to wear it at all times. Sent home, they were instructed to resume “normal life”.49

The Utai tried as best as they could to do so, in the face of a severe lack of food and perpetual fear of the Japanese. By a strange twist of history, the Japanese also admired the Utai. As a nation, they remembered how in 1904 the Jewish American financier Jacob Schiff had gifted Japan $200 million in support of the Russo-Japanese War. Following that, the Japanese had even conceived of the Fugu Plan, offering Jewish poeple an “Israel in Asia” as a new homeland.50

Nathan recalls:

“[A Japanese official] stopped me in the street and examined my armband closely. ‘You what-ka?’ he asked. I answered in as firm a voice as I could muster, ‘I am a Jew.’ To my astonishment, he grasped my hand and shook it energetically, smiling broadly. ‘Ah Jew!’ he exclaimed. ‘Werry [sic] good! In the world three great J’s – one Japan, two Julius Caesar, three Jew!’”51

True to their unpredictability, the Japanese suddenly interned more than 100 Jewish men on 5 April 1943. They were imprisoned at Changi camp, where they were largely left to continue their way of life. No one knew why they were captured, but after the war, a story circulated that a German ship had arrived in Singapore – its officers instructed the Japanese to “do something” with the Jewish people.52

Ironically, the Japanese Occupation deepened the local Jewish identity, which was already moving away from Asian Britishness. Meyer’s Maghain Aboth Synagogue became a refuge for what remained of the Jewish community, who gathered there to pray regularly. Stockbroker and philanthropist Jacob Ballas recounts how he became more conscious of Judaism during those lean years. He even started donning the tefillin (Jewish phylactery).53

By the time the war ended, less than 700 Jewish people remained. Even the wealthy found their homes destroyed, but the two synagogues had been largely left unscathed. Over the next few decades, the Jewish population was to steadily decline in numbers, but one last gasp of prominence was to come.54

Only a Sensation of Independence

In 1955, David Marshall was elected Singapore’s first chief minister. His victory represented, in the political sense, the rise of the Baghdadi Jewish community and its Zionist movement. In his capacity, Marshall was responsible for giving Singapore its first taste of internal self-government, setting the colony on the path to full independence.

Yet, after the height of Marshall’s 1956 All-Party Constitutional Mission to Whitehall, his political career, mirroring the fate of the Baghdadi Jews, descended, ending in his loss in the 1963 general election. By 1990, when the Baghdadi community had dwindled to a mere 180, Marshall mourned, “This remnant of a lost tribe is disappearing… We are a vanishing community.”55

Marshall could take comfort in a few victories, at least. When Singapore achieved independence, Judaism was recognised as one of Singapore’s eight official religions. The Mahallah and its surrounds were gazetted in 2003 under the Mount Sophia Conservation Area,56 and the Maghain Aboth as a national monument in 1998. And, other Jewish children never again heard the taunt, “Jaudi Jew, brush my shoe, bring it back at half-past-two.” When Marshall was bullied with that racial epithet on the first day of school, he punched the boy in his face.57

As a new nation, Singapore built on its Zionist links. By 1956, Francis Thomas, the Minister for Communications and Works, exhorted Singapore to “learn a lot from the spirit which has turned the small State of Israel from a desert into a garden”.58 In 1969, full diplomatic relations were established between Singapore and Israel, even if they were kept in the “closet”.59

In 2000, former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew revealed that the Israel Defence Force had helped establish the Singapore army. “To disguise their presence,” he wrote, “we called them ‘Mexicans’. They looked swarthy enough.” The secret identities of the Israeli military mission, headed by then Colonel Yaakov (Jack) Elazari, was invented “in order not to arouse suspicions among the Malay Muslims”. In less than a year, Elazari, with the assistance of the Mossad, trained 200 commanders, and wrote the founding manuals for the Singapore army and intelligence body.60

More recently, American, Australian and other European Jewish people have joined Singapore’s Israeli expatriates. In order to survive, the Baghdadi community found that they had to open themselves up, and through the Jewish Welfare Board, focus on cohesion between the different “blood groups” by catering to a “fuller Jewish life”. However, as with the Sephardis and Ashkenazis, there remains “a social and cultural distance” between the old and new communities.61

This manifested itself most clearly in the 1991 establishment of the United Hebrew Congregation (UHC). Formed by an expatriate group of mostly Westerners, the UHC brands itself as an “egalitarian, inclusive, progressive Jewish community”, in contrast to the Orthodox Sephardic practices of the Maghain Aboth.62 The differences between the three communities – Baghdadis, Israelis and Westerners – is somewhat bridged by the Gesher programme, which aims to “foster interaction and understanding” between them.63

However, by 1957, when undergraduate Appu Raman began his study of the Jewish community in Singapore, signs of the diminishment of community feeling were already apparent. “The younger generation is drifting away from all good principles of the Jewish community,” one Mr N. tells him. A contradictory sense of self-identification also manifests itself. Mr N. continues, “In public life one should forget about his community and think in terms of the people of Singapore. I know it is difficult to be a Jew but all the same being born a Jew I am a Jew.”64

The Collective History of Amnesia

“Being a Singaporean means forgetting all that stands in the way of one’s Singaporean commitment,” S. Rajaratnam famously defined in 1969.65 Our founding Culture and Foreign Minister also reflected, “The contributions the Singapore Jews have made to the development of Singapore are out of proportion to their numbers, which goes to show… that what counts is quality not quantity.”66

Despite or perhaps because of their minority, the Singapore Jewish community parallels other ethnicities’ self-development. They were compelled to forget their past in order to identify precariously as Singaporean – a construct that simultaneously celebrates and plays down different ways of life.

More particularly, the dispersed Jewish community presents a difficulty to urban and heritage planners. How can one identify a singular cultural enclave like Chinatown, if the places where the group worked, lived, played and prayed are geographically scattered and, in spirit, dissipated? One could argue that the preservation of many of the Mahallah’s buildings suffices. Yet, a 2010 Preservation of Monuments Board walking tour only featured the Maghain Aboth, and conflated Armenian and Jewish history with a stop at the Church of St Gregory the Illuminator. Despite the two community’s historical links, each deserves to be called by their name, which surely is not “Other”.67

Furthermore, Singapore’s lack of preservation of burial sites renders many cultural enclaves soul-less. The Jewish community believes that “[e]ven the dead will be resurrected”, as a member of the community told Raman. “That is why in Singapore we had to resist the Government’s plan to take over the Orchard Road Cemetery… We cannot exhume our dead. Not a single bone of the dead shall be crushed; that is the law.”68

In fact, the Jewish community hit a low point when all graves in the Orchard Road and Thomson cemeteries were exhumed and moved to the Choa Chu Kang Cemetery – a fate that seems ready to befall the historic Chinese cemetery of Bukit Brown.69 As a result, some Jewish families took the chance to re-inter their ancestors in Israel. Future generations of Singaporeans were thus denied the chance to learn about and be with their forebears.

As with Singapore, other cities in Asia display a complex “port Jewish” identity; academic Jonathan Goldstein has identified Manila and Harbin as prime examples.70 It would be instructive to study how Jewish identity is preserved in those cities to learn how best to do justice to such small, proud and unjustly “other-ed” communities.

But the onus is on people, not power, to remember and, more importantly, react. Retrace Jewish paths: the Mahallah, Waterloo Street, Oxley Rise, the Choa Chu Kang Jewish Cemetery and even Jurong. Listen carefully. Shalom, their shophouses, synagogues and tombstones will faintly but distinctly whisper. Peace be unto you.

REFERENCES

Barzilal, Amnon. (2004, July 16). A deep, dark, secret love affair. Retrieved from haaretz.com website.

Bieder, J. (2007). The Jews of Singapore. Singapore: Suntree Media. (Call no.: RSING 959.57004924 BIE)

Blackburn, K., & Hack, K. (2012). Memory and nation-building in Singapore (pp. 292–333). In War memory and the making of modern Malaysia and Singapore. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 940.53595 BLA)

Boey, K.C. (2012). Clear brightness: New poems. Singapore: Epigram Books. (Call no.: RSING S821 BOE)

Chan, H.C. (1984). A sensation of independence: A political biography of David Marshall. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 324.2092 CHA)

Goldstein, J. (2004, Autumn/Summer). Singapore, Manila, and Harbin as reference points for Asian ‘Port Jewish’ identity. Jewish Culture and History, 7 (1–2), 271–295.

Kamsma, T. (2010). The Jewish diasporascape in the Straits. Amsterdam: VU University. (Call no.: RSING 338.04089924 KAM)

Lim, W.J.D. (2013, January). The original sin of Singapore’s history. Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, 12 (1). Retrieved from QLRS.com website.

Nathan, E. (1986). The history of Jews in Singapore, 1830–1945. Singapore: HERBILU Editorial & Marketing Services. (Call no.: RSING 301.45192405957 NAT)

National Heritage Board. (2017, December 1). Monumental walking tours. Retrieved from National Heritage Board website.

People’s Action Party (Singapore). Jurong Branch. (1996). Jurong journeys. Singapore: Oracle Works. (Call no. RSING 959.57 JUR)

Raman, A. [1958]. A study of the Jewish community in Singapore. Singapore: University of Malaya. (Call no.: RCLOS 305.892405957 A)

Singapore Jews. (2010). The Jewish Community of Singapore. Retrieved from SingaporeJews.com website.

Sorkin, D. (1999, Spring). The Port Jews: Notes toward a social type. Journal of Jewish Studies, 50 (1), 87–97.

Tan, K.Y.L. (2008). Marshall of Singapore: A biography. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 959.5705092 TAN)

United Hebrew Congregation. (2013). United Hebrew Congregation (Singapore). Retrieved from United Hebrew Congregation website.

Urban Redevelopment Authority (Singapore). (2010). Mount Sophia conservation area. Retrieved from Urban Redevelopment Authority website.

Yeo, K.W. (1985, September). David Marshall: The rewards and shortcomings of a political biography. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 16 (2), 304–321. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

NOTES

-

PAP, Jurong Branch , 1996, p. 30. ↩

-

Jurong is possibly named after the city of Jurong in Jiangsu, China, as there are already mentions of “Soongie Jurong” (Jurong River) in 1837. ↩

-

Also known as Jacob Saphir (1822–85). ↩

-

Nathan, 1986, p. 2; Orchard Road’s considerable distance from Synagogue Street made livayah (funeral) difficult, which requires bodies to be carried on a bier to the cemetery. See Beider, 2007, pp. 23–24. ↩

-

Historian David Sorkin’s concept: “port Jews” were lucky to find themselves in ports that valued international trade. Because of their commercial utility, they gained some social acceptance and legality. In terms of identity, port Jews had lax religious observance, yet actively identified as Jewish. ↩

-

That night, Solomon showed Thomson his Torah, the holy Hebrew scriptures, discussed Jewish religious law, and confessed the torture he had suffered at home. See Thomson, J.T. (1984). Glimpses into life in Malayan lands. New York: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.5 THO) ↩

-

Theo Kamsma points out that Jews were either identified as Arabs or “other Orientals”. “That has [historically] made Jews, as a separate category, almost unrecognisable.” See The Jewish Diasporascape in the Straits, 2010, pp. 92–94. ↩

-

Goldstein, 2007, p. 3. ↩

-

It would be interesting to analyse David Marshall’s early writings for their influence on his politics, like The Short Stories and Radio Plays of S. Rajaratnam, 2011), though Nathan warns that “the standard was not higher than the average school magazine”, Nathan, 1986, p. 82. ↩

-

“I am both a Jew and an Asian,” Marshall famously pronounced. He was especially popular among the Chinese for his anti-colonial, pro-labour, and principled democratic stance. See Thum, P. (2011, June). Living Buddha: Chinese perspectives on David Marshall and his Government, 1955–1956. Indonesia and the Malay World, 39 (114), 245–267. ↩

-

Blackburn & Hack, 2012, pp. 301—333. ↩

-

Beider, 2007, p. 195; Yeo, Sep 1985, p. 304; Goldstein, 2007, p. 4. ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority, 2010. ↩

-

Quoted in Goldstein, 2007, p. 5. ↩

-

Quoted in Barzilai, 16 Jun 2004. ↩

-

United Hebrew Congregation, 2013. ↩

-

Quoted in Lim, 2013. ↩

-

The “Chinese, Malay, Indian, Other” racial nomenclature was introduced in 1965, largely borrowing from British census taking. The Jewish community, along with other minorities of minorities, were reductively classed as “Other”. ↩

-

Goldstein, 2007. ↩