The Invention of a Tradition: Indo Saracenic Domes on Mosques in Singapore

The typically onion-shaped Indo-Saracenic domes that crown the city’s mosques are a late-1920s introduction to Singapore’s architectural landscape.

Domes are typical features of Singapore mosques today. However, this was not always the case. In fact, domes were introduced into Southeast Asian mosque architecture only in the 19th century.1 This trend can be observed in Singapore and within the wider Malayan-Indonesian mosque landscape. This article will discuss the proliferation of domes on mosques in Singapore by considering how the Indo-Saracenic dome became an “invented tradition” as a typical mosque feature on the island beginning with the construction of the Sultan Mosque in the late 1920s.2

The present Sultan Mosque in Kampong Gelam was not the first mosque on the site. Its stylistic contrast with the previous 19th-century mosque that it replaced reflects the changing trends in mosque architecture in Singapore. Instead of the typical four-square-plan mosque with a multitiered pyramidal roof that typified traditional mosque architecture in maritime Southeast Asia, the Sultan Mosque was commissioned in the Indo-Saracenic style characterised by domes and arches.

The most distinctive feature of the Indo-Saracenic style is its dome. This type of dome has a distinctive ogee profile and is sometimes referred to as an “onion dome”. Over time, the Indo-Saracenic dome was abstracted from the repertoire of Indo-Saracenic features and adapted to local mosques. The dome eventually turned into an identity symbol for mosques in Singapore.

The Indo-Saracenic style is closely associated with British imperialism. The British created the Indo-Saracenic style in 19th-century India by combining Western architectural ideas with what they thought were the most representative features of the Hindu and Islamic architecture of India. The word “Saracenic” was used in a broad sense to denote “Islamic”, while “Indo” morphed from the word “Hindu”.3 In Singapore, the decision to build a mosque in the Indo-Saracenic style in the 1920s raises questions about how this style was viewed by local mosque trustees. Viewed through the theoretical lens of postcolonial criticism, the Sultan Mosque becomes another product of the imperial project. However, a consideration of the details surrounding the commission of the design reveals another perspective.

This article will consider the importance of “local agency” (choices made by local Asian community leaders in colonial Singapore) in both the transplantation of the style into Singapore and the abstraction of the dome as a potent symbol of mosques. The Board of Trustees and Building Committee of the Sultan Mosque commissioned Swan and Maclaren, arguably Singapore’s preeminent architectural firm in the 1920s, and the design was carried out by the firm’s Irish architect, Denis Santry. It was through this collaborative relationship between Asian Muslims and a Western architect that a new vocabulary of domes and decorative minarets was introduced into Singapore’s mosque architecture.

The Indo-Saracenic Style

The choice of Indo-Saracenic style for the Sultan Mosque may be viewed as a culmination of a number of factors beginning with the birth of the style in British India, notions of modernity and Islamic aesthetics, and, last but not least, British colonialism in Malaya.

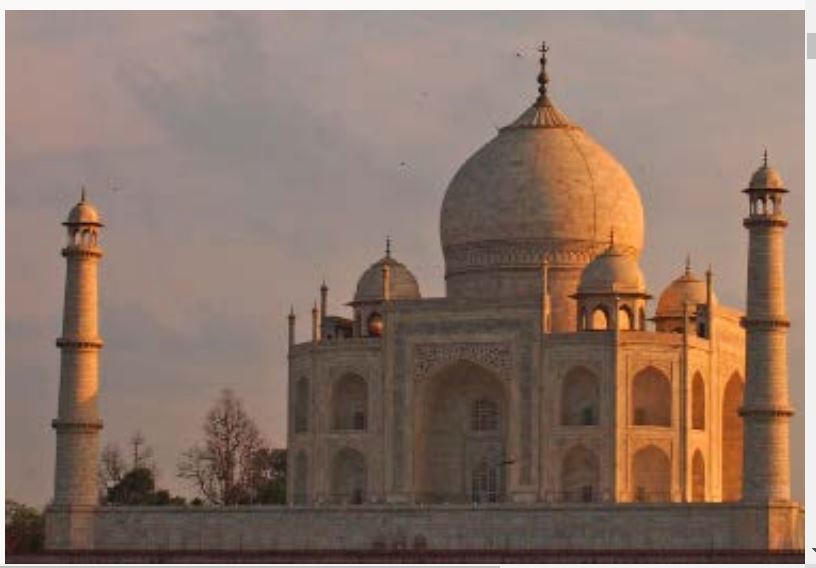

The Indo-Saracenic architectural style flourished in India from the last third of the 19th century to the early 20th century under British patronage.4 British imperialists in India regarded the Indo-Saracenic style as an appropriate expression for public buildings that would help legitimise British rule by presenting an image of continuity with the past.5 The style combined elements of Hindu and Indian-Islamic architecture with Western architecture. Indian-Islamic architecture was, in turn, derived from a synthesis of Central Asian and Persian features with indigenous Indian architectural features. For the British Raj, the Indo-Saracenic style was associated above all with the grandeur of the Mughal empire, whose majestic palaces and mausoleums were much admired by the British.6

For all their apparent references to the traditional architecture of India, Indo-Saracenic buildings were in fact constructed with the most up-to-date European structural engineering, creating buildings that were at once modern and historical, Asian and Western.7 In British India, the Indo-Saracenic style found its way into all sorts of government buildings and public buildings such as museums, railway stations and educational institutions. Thus, the Indo-Saracenic style was also associated with progressive institutions and, by extension, modernity.8

The British introduced the Indo-Saracenic style into Malaya in the late 19th century, with the view that such a style was appropriate for a region with a Muslim majority. However well intentioned, this Islamic aesthetic was misplaced because the Indo-Saracenic architectural style had no relevance or precedence in the Malayan architectural tradition.9 The cluster of public buildings erected by colonial architects for the British government still standing around the Dataran Merdeka in Kuala Lumpur today is representative of the Indo-Saracenic style in early 20th-century Malaya. Soon, Indo-Saracenic elements began to proliferate in Malaya as the local architectural environment adapted the style to various types of buildings, ranging from local mosques to commercial buildings. An example of a Singapore commercial building designed in the Indo-Saracenic style is the now-demolished Alkaff Arcade, designed by David McLeod Craik and opened in 1909 at Collyer Quay.

While the Sultan Mosque was certainly not the first mosque in Singapore with Indo-Saracenic features, it was the first and perhaps only mosque in Singapore to be conceived in this style in its entirety. A mosque that predates the Sultan Mosque, the 1907 Abdul Gafoor Mosque, contains some architectural features that could be labelled Indo-Saracenic, such as its highly ornamental roof terrace of decorative minarets and a central octagonal turret capped by a dome. However, it falls short of being truly “Indo-Saracenic” because of the lack of a full-profile and monumental dome. This is further compromised by the presence of heavily moulded frieze, capitals and plasters that evoke (Western) classical architecture. This is a fusion building, with an eclectic mix of decorative features taken from both Western and Indian-Islamic architecture. However, it might be seen as a first step towards the adoption of Indo-Saracenic architecture by the local Muslim community.

A New Architectural Style for Mosques

An undated photo in the Sultan Mosque’s collection, probably taken in the early 20th century, shows a four-tier pyramidal hip roof superstructure supported by a whitewashed square pillar, in a compound enclosed by white walls. This is the former Sultan Mosque, which was purported to have been completed by 1824 under the patronage of Sultan Hussein Shah.10 Stamford Raffles had promised the Sultan $3,000 towards its construction.11 The British had established a foothold in Singapore in 1819 through the East India Company, and Singapore was in its early stages of expansion as a British trading post. The building was of brick construction, but its architectural form still adhered to traditional Southeast Asian timber mosque architecture. The oldest existing mosque of this type in Malaya is the Kampung Laut Mosque in Kelantan, claimed by some to have been built in the 16th century.12

Although the original Sultan Mosque functioned as the royal mosque of the sultan in early Singapore, control of the mosque eventually passed from the sultan to local Muslim community leaders. In 1879, Sultan Alauddin Alam Shah, also known as Tengku Alam, the grandson of Sultan Hussein Shah, turned the administration of the mosque over to a five-member council.13 A board of trustees was appointed after 1914 to oversee the mosque. The 12-member trustee system ensured representation from various ethnic communities across the board by appointing two members from each major Muslim community in Singapore – Arab, Bugis, Javanese, Malay, North Indian and Tamil/South Indian communities.14 This was the system of governance in place when the construction of a new mosque was mooted in 1924, and Denis Santry was commissioned to design the new mosque.

Santry may have modelled his design after the Taj Mahal15 – the Mughal mausoleum which was greatly admired by British proponents of the Indo-Saracenic style.16 The four minarets at the corners of the Taj Mahal complex have been replicated at the four corners of the roof of the Sultan Mosque. The shafts of the minarets follow the same gentle tapering outline and are similarly topped with chhatris.

Chhatris are domed circular or polygonal pavilions that became highly ornamental features in Islamic architecture in India, and were in turn absorbed into the Indo-Saracenic decorative vernacular. Instead of a central and extremely monumental dome as seen on the Taj Mahal, two domes with a diameter of 40 feet each are positioned on opposite sides of the Sultan Mosque, one above the elevation facing North Bridge Road, and another over the main entrance to the mosque, facing the present Bussorah Mall. Flanking the monumental onion domes that rise above the corner minarets to 100 feet above ground level are four chhatris, just as four chhatris surround the Taj Mahal dome.

The facade facing North Bridge Road is decorated with the pishtaq motif. The doors open directly into the chamber containing the grave of Sultan Alauddin Alam Shah, who passed away in 1891.

Ornamental crestings fringe the edge of the roofline similar to those found on the Friday Mosques in Kuala Lumpur, Delhi and Lahore. The first is in the Indo-Saracenic style, designed by Arthur Benison Hubback in 1909, and the latter two mosques are iconic structures from the Mughal period of Indian-Islamic architecture. Decorative pinnacles are topped with stylised lotus buds; they project at intervals from the edge of the roofline, and spring from different heights off the decorous elements on the terrace of the roof. Like the Taj Mahal, the central portion of the facade facing North Bridge Road (the section directly beneath the dome) is executed with the pishtaq motif – an Iranian-derived portal design consisting of a monumental pointed arch set within a rectangular frame decorated with bands of ornamentation.

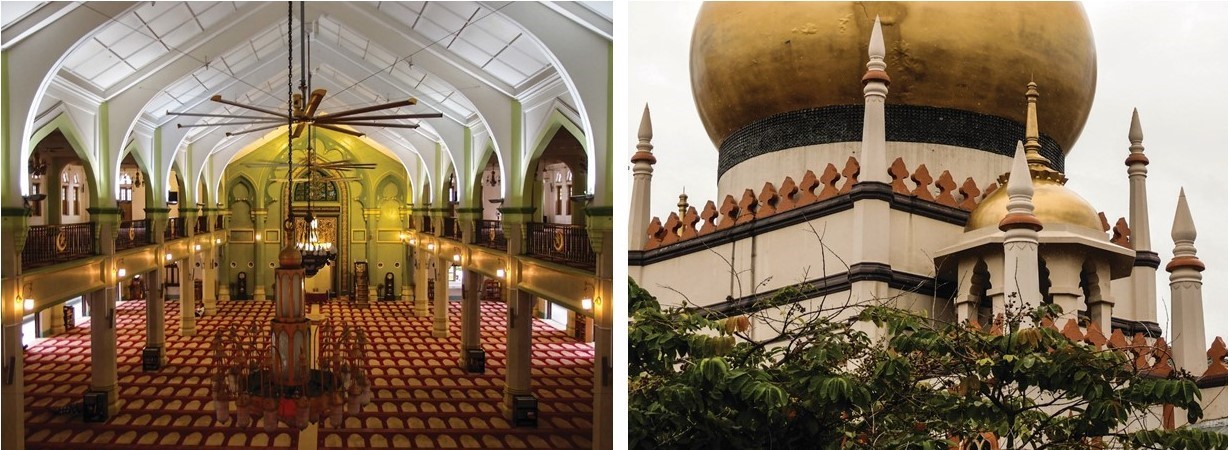

The mosque is elevated about 10 feet above the ground, with double staircases leading to the main entrance. There is one auxiliary entrance on each of the long sides of the mosque. The main entrance porch is designed in the form of a chhajja, a classical Indian rectangular pavilion with elaborate overhanging eaves. This feature was absorbed into Indian-Islamic architecture, and later into the Indo-Saracenic style. The series of arches that run from the back of the prayer hall to the qibla wall, and perhaps all the window and door frames within the building, as well as the mouldings on the qibla wall, are in the form of pointed-arches, multifoil arches or cusped arches. These hallmark Indo-Saracenic shapes were assembled from both European and Indian arch traditions.

Contributions of Local Agents

Unlike the Abdul Gafoor Mosque and the Friday Mosques noted previously, the Sultan Mosque is an enclosed mosque, and was reportedly one of the largest enclosed mosques in the world at the time it was built.17 Its floor area measures approximately 106 by 180 feet. The sides and back portion of the prayer hall are split to incorporate a second-floor gallery. The mosque has room for 5,000 worshippers and cost about $250,000 to construct.18 The new Sultan Mosque was officially opened on 27 December 1929, the last Friday of the year, although it was completed only in 1932.19

The heart and soul behind the construction of the mosque was Mahmood bin Haji Dawood, a merchant and well-respected community leader of “Bombay origins”.20 He supervised the project from the start until his untimely death in 1931 and is remembered as the “builder” of the Sultan Mosque. Dawood first convened a meeting on 1 January 1924 to propose the construction of a new mosque to replace the dilapidated existing building. A four-member Building Committee was established to oversee the project on this occasion.21 Besides the uncertain identity of a “Mr Ismail”, the other three members of the committee were well-known merchants and community leaders: Syed Abdur Rahman bin Shaik Alkaff, J.P. as nominated chairman; Dawood as the honorary secretary and treasurer; and Shaik Salim bin Taha Mattar as a member. All three community leaders signed their names as “owners” representing the Sultan Mosque on the building plans submitted to the Municipal Commission.22

This was a mosque that the Singapore Muslim community could be proud of. When funds were not forthcoming in 1926, and appeals for funding made to the Sultan of Johor and the colonial government proved unsuccessful, a meeting was called by the Building Committee. Thirty-seven committee members were elected to represent the Muslim community of Singapore with the expectation that they would solicit funds from their respective ethnic communities. The various communities included the Arab, Bombay, Bugis, French Muslim (probably referring to Muslims originating from the French colony of Pondicherry), Javanese, Madras, Malay, Pathan, Punjabi and South Indian communities.23

Construction of the new mosque began in 1928 after four years of initial fund-raising and planning.24 The Building Committee was most likely responsible for decision-making relating to the new mosque, including the approval of Irish architect Denis Santry of Swan and MacLaren to design it. Santry was active in Singapore from 1919 to 1934, and his work included the Tanjong Pagar Railway Station and the Telok Ayer Methodist Church.25 Several features in the physical design of the mosque point to a client-architect relationship that was consultative and collaborative.

Viewed from the exterior, the Sultan Mosque appears to be a unitary building, but it actually contains two separate domains: the prayer hall with its auxiliary verandahs, and a royal grave within an enclosed chamber behind the qibla wall, on the side facing North Bridge Road. This is the grave chamber of Sultan Alauddin Alam Shah who passed away in 1891. Incorporated into the new building, the grave is located beneath the western dome, and can be accessed directly from the exterior of the building through a set of double doors facing North Bridge Road.26

When seen from North Bridge Road, the space behind the pishtaq motif appears to be connected with the rest of the building, but this grave chamber is in fact physically walled off from the other parts of the building. Thus, although structurally part of the overall mosque building, it is segregated spatially and is symbolically distinct – a neat solution that accommodates the resting place of the sultan without integrating his grave into the space of worship, which is a contentious subject within Islam. Such detail would have required giving specific instructions to Denis Santry, a Christian, in order to work out a design that made such spatial distinctions within one building.

(Right) The dark band encircling the dome is made of glass bottles contributed by the poor. A chhatri is positioned next to the dome in the company of decorative pinnacles with stylised lotus buds. Courtesy of Ten Leu-Jiun.

The second detail that reveals local intervention is a dark band accentuating the division between each dome and its drum support. Each band is made up of rows of glass discs, arranged around the “necks” of the two gigantic domes. Oral tradition has it that soya sauce bottles were offered to the mosque by poor people in Kampong Gelam, and the Building Committee gave the bottles to the architect to see what he could do with them.27 Whether it was Santry’s or the committee’s idea to collect the bottles, this visible and unusual design intervention may have fostered a sense of community ownership of the dome design. It may also be regarded as evidence of the collaborative relationship between the architect and his clients. It should be no surprise that the architect listened to suggestions by the committee members. After all, it was they who approved the payment of the architect’s fee.

The Dome Takes Root

The impact of the Indo-Saracenic style and its iconic dome was almost immediately felt among local mosques. The next mosques to lead the trend were the Alkaff Mosque built in 1932 and the new prayer hall of the Hajjah Fatimah Mosque, designed in 1933.28 Domes were variously placed on the minaret, above the porch-like structure at the facade, and on the gate posts of the Alkaff Mosque. This mosque with a distinctive curved gable was located on Jalan Abdul Manan, off Jalan Eunos. It was demolished around 1995, when a new mosque was erected nearby to replace it.29

The Hajjah Fatimah Mosque was built in around 1845.30 When a decision was made to rebuild the prayer hall in 1933, Syed Abdul Rahman bin Taha Alsagoff, a descendant of Hajjah Fatimah, commissioned local Chinese firm Chung and Wong to design it in the Indo-Saracenic style. The prayer hall is dominated by a prominent dome supported by a drum lit by 12 stained-glass windows. From the exterior, the pointed arches around the verandah are flanked by demi-columns that rise above the edge of the roofline into full shafts topped by chhatris. The decision to use this style and its design by a Chinese firm indicate that the Indo-Saracenic style had become localised in Singapore. The Malabar Mosque on Victoria Street, opened in 1963, also used the decorative elements of monumental domes, chhatris and a domed minaret.

The roof of the former Haji Yusoff Mosque at Upper Serangoon represented a synthesis of the two roof traditions. An onion dome took the place of what would otherwise have been the uppermost pyramidal apex of a three-tier roof structure. This prominent dome rested atop a levelled-off two-tier roof. The Haji Yusoff Mosque was rebuilt in 1995.

Over time, a popular two-dome scheme emerged for the design of mosques in Singapore, featuring a main dome over the mosque building and a smaller dome over the minaret. Some examples are: “Singapore’s last kampong mosque”, the Masjid Petempatan Melayu Sembawang built in 1970,31 the demolished Muhajirin Mosque in Toa Payoh built in 1977 and the 1980 Masjid An-Nur in Woodlands.

While better-endowed mosques were rebuilt with gleaming domes integrated into their designs, the humble kampong mosques followed suit simply by capping a dome over an otherwise functional pitched zinc roof, such as the demolished Kampong Bedok Laut Mosque and the still standing Hussein Sulaiman Mosque on Pasir Panjang Road.

The dome, idealised in the onion shape, has come to be regarded by many as an indispensable symbol of a mosque. According to Abdul Halim Nasir, writing about mosques in Malaysia, “Many people feel that a mosque is not really complete without the onion-shaped dome. This feeling has created restlessness and as a result mosques built during the precolonial and colonial period without the onion-shaped domes have had the roofs radically modified so that an onion-shaped dome can be built.”32 In an interview with The Straits Times, Dr Y.A. Talib, an Islamic studies expert, said that domes were not compulsory on mosques, and were placed on mosques in different parts of the world out of the owners’ preference.33 The preponderance of domed mosques in the vernacular architectural environment in Singapore is thus an indication of a popular sentiment in favour of domed mosques.

The diffusion of the dome within the vernacular architectural environment in Singapore began in the early 20th century. This development highlights the active presence of local agents in creating meaning and significance that matched their ideals of what a mosque should look like. After all, domed mosques have long been common throughout the Islamic world, especially in the Middle East. For trustees of the Sultan Mosque in the 1920s, the Indo-Saracenic style was a novel design that fused traditional Islamic stylistic elements originating outside of Southeast Asia with a technologically advanced structure of reinforced concrete designed in monumental proportions. The design and scale of the mosque were especially striking in an urban environment still dominated by two-storey shophouses.

Postcolonial critics and architectural purists who champion regionalism might lament the proliferation of domed mosques in place of a long-time native architectural form, namely, the multitiered-roofed mosque. Nevertheless, the “new” architecture received the endorsement of the local Muslim community. Moreover, the new style brought regional mosque architecture stylistically closer to the ummah (the global Muslim community) in terms of its formal expression.

This article highlights the multilayered meanings that can be embodied by architecture with hybrid features created in a colonial city. Swati Chattopadhyay has noted the “inordinate emphasis in architectural and planning scholarship on first acts and initial designs” that has helped to create narratives in which the colonisers are portrayed as “the only active agents on the scene, relegating the colonized population to the role of passive inhabitants or, at best, resistors of domination”.34

The Sultan Mosque challenges such narratives and assumptions by showing that the British-Indian Indo-Saracenic style was embraced by local Muslim community leaders in Singapore for their own reasons and purposes. Their agency led to the incorporation of domes into the local idea of what a normal, modern mosque should look like, and thus created a new tradition in local architecture.

REFERENCES

Abdul Halim Nasir. (2004). Mosque architecture in the Malay world. Bangi: Penerbit University Kebangsaan Malaysia. (Call no.: RSEA q726.20959 ABD)

Alsagoff, Syed Abu Bakar. (1988). Mosques in Singapore 1988 = Masjid-masjid di Singapura 1408H. Singapore: Muslim Assistance Service Publications. (Call no.: RSING 297.35095957 MOS)

Buckley, C.A. (1965). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.57 BUC)

Cannadine, D. (2002). Ornamentalism: How the British saw their empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: R 305.52 CAN)

Chattopadhyay, S. (2005). Representing Calcutta: Modernity, nationalism, and the colonial uncanny. London: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 954.147 CHA)

Frishman, M., & Khan, H.-U. (Eds.). The mosque: History, architectural development & regional diversity (pp. 225–240). London: Thames and Hudson. (Call no.: RART 726.209 MOS)

Hadijah Rahmat., et al (Eds.). (2007). The last kampong mosque in Singapore: The extraordinary story and legacy of Sembawang. Singapore: Masjid Petempatan Melayu Sembawang. (Call no.: RSING 297.355957 LAS)

Hobsbawn, E., & Ranger, T. (Eds.) (1983). The invention of tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Lee, E. (1990). Historic buildings of Singapore. Singapore: Preservation of Monuments Board. (Call no.: RSING 720.95957 LEE)

Masjid Sultan (Singapore). (1968). Sejarah ringkas Masjid Sultan Singapura. Singapore: [Jawatankuasa Pentadbir Masjid Sultan]. (Call no.: RCLOS 297.351095957 SEJ)

Metcalf, T.R. (1989). An imperial vision: Indian architecture and Britain’s Raj. London: Faber and Faber. (Call no.: RART 722.44 MET)

Metcalf, T.R. (1998). Past and present: Towards an aesthetics of colonisation (pp. 12–25). In G.H.R. Tillotson (Ed.), Paradigms of Indian architecture: Space and time in representation and design. Surrey: Curzon. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Mohamad Tajuddin Haji Mohamad Rasdi. (2000). The architectural heritage of the malay world: The traditional mosque. Skudai, Johor Darul Ta’zim: Penerbit Universiti Teknologi Malaysia. (Call no.: RSEA 726.209595 MOH)

Tillotson, G.H.R. (1989). The tradition of Indian architecture: Continuity, controversy and change since 1850. New Haven: Yale University Press. (Call no.: RART 720.954 TIL)

NOTES

-

Hobsbawn & Ranger, 1983. ↩

-

Metcalf, 1989, pp. 77–90; Tilloston, 1989, pp. 46–56; Cannadine, 2002, pp. 148–149. ↩

-

Current literature refers to the former mosque as the one built in 1823 or 1824. However, in 1926, a newspaper article reported that this mosque was the second building at the site. The Singapore Free Press, 4 Nov 1926, p. 11. ↩

-

Sultan Mosque, 1965, pp. 107, 160. ↩

-

Mohamad Tajuddin Haji Mohamad Rasdi, 2000, pp. 53–60. ↩

-

Sultan Mosque, 1965, p. 31. ↩

-

Sultan Mosque, 1965, p. 32. ↩

-

Haji Asmawi bin Said, executive administrator of Sultan Mosque, personal interview with the author. Sultan Mosque, 11 Sep 2012. ↩

-

New Sultan Mosque at Kampong Glam. (1930, January 1). The Singapore Free Press, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sultan Mosque, 1965, p. 33; Sarwar, H.G. (1925, June 29). The Sultan Mosque. The Singapore Free Press, p. 8; Sultan Mosque repairs. (1948, June 22). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

New Sultan Mosque at Kampong Glam. (1929, December 30). The Singapore Free Press, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; The Singapore Free Press, 1 Jan 1930, p. 10; The Masjid Sultan. (1932, April 5). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Death of M.H. Dawood. (1931, November 25). The Singapore Free Press, p. 12; Kampong Glam Mosque. (1932, July 7). The Singapore Free Press, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 4 Nov 1926, p. 11. ↩

-

Building Plan 269/1924, National Archives of Singapore Microfilm Reel NA309. ↩

-

Meeting of Muslims. (1926, February 19). The Singapore Free Press, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Masjid Sultan, Kampong Glam. (1928, July 2). The Singapore Free Press, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Mr Denis Santry leaves after fifteen years. (1934, March 8). The Singapore Free Press, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Sultan Mosque. (1925, September 2). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sultan Mosque, 11 Sep 2012. ↩

-

Building Plan 128/1933, National Archives of Singapore Microfilm Reel CBS96. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2018, April). Alkaff Kampung Melayu Mosque written by Herwin Mohd Nasir. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

Hadijah Rahmat, 2007. ↩

-

Abdul Halim Nasir, 2004, p. 99. ↩

-

Kulatissa, S. (1984, August 31). Building domes among skyscrapers. The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chattopadhyay, 2005, p. 9. ↩