Writing to Print: The Shifting Roles of Malay Scribes in the 19th Century

The practice of copying and recopying Malay manuscripts can be viewed as a simultaneous act of reading and writing in which the Malay scribe actively interprets and reinterprets the text as he copies. Through this process, the Malay scribe makes the text copies accessible to his intended reader.

Human beings communicate primarily through speech, and then writing. To write is to leave marks on paper or other surfaces that someone else can read at a later date to understand the message contained without requiring the writer’s presence. Writing, then, refers to the systematic representation of language in visual form or, for those with visual difficulties, in tactile form.1 Writing systems, however, can be renovated or replaced. In the case of the Malay language, the contemporary standard of writing in the Romanised alphabet, or Rumi, replaced an earlier system known as Jawi, which employs a form of modified Arabic script and was in use for at least 700 years. One of the oldest artefacts containing Jawi script is an engraved stone, Batu Bersurat Terengganu, discovered in 1899 and estimated to date from the 14th century. In contrast, Rumi writing has only been in mainstream use in Singapore and the Malay Peninsula for the past 60-odd years. Consequently, Malay manuscripts written in Jawi have been inadvertently rendered less accessible for the modern audience.

Writing and Reading Malay Manuscripts

In composing a sentence, a writer essentially pens combinations of signs drawn from a predefined set (an alphabet) that correspond to specific sounds of speech. These combinations are then deciphered by the reader according to rules commonly understood amongst speakers of the particular language. Reading itself is broadly defined as the act of extracting information from any encoded system and processing the extracted information to form meanings.2 A reader’s understanding of a text may shift as meanings are contingent upon the time and place in which the text is read, relative to the time and place in which the text is produced. Moreover, individual or collective interpretations can also be shaped by other sociocultural factors such as familial upbringing or prevailing moral values.

The practice of copying and re-copying manuscripts can be viewed as a simultaneous act of reading and writing whereby the Malay scribe (penyalin) actively interprets and reinterprets the text as he copies. The larger role of the Malay scribe is to render the text copies accessible to his intended reader. Hence, he also assumes the mantle of author/editor as amendments are made. A good scribe should possess an intellectual inventiveness capable of recontextualising a text for better audience engagement. It is important to note that the scribe often strived to preserve the ideas and vocabulary of the original texts and that they were rarely altered whimsically. A good case study is the translation of the Indian Mahabharata into Malay – Pandawa, where tales from the former were translated and adapted into more secular versions in tandem with Islamic beliefs.3 With adaptation, it is commonplace to find several versions of the same text with variations on editorial and linguistic styles. The aforementioned variations make it possible to trace either genealogies or networks of copyists from a group of texts as well as provide some insight into the intellectual and cultural environment of the time as the scribes react and respond to each other’s style and commentaries.

Only a fraction of Malay manuscripts survive today, and their limited numbers impede a full understanding of the history and development of Malay writing. From the Malay perspective, however, the physical manuscript is not as valued, even when a manuscript is kept for ceremonial or heirloom purposes, due in part to the hot and humid conditions of tropical Nusantara (the Malay-Indonesian Archipelago), which ensure the limited shelf lives of these manuscripts. Consequently, knowledge transmission via text is not entirely dependent on the preservation of physical manuscripts. Between the 16th and 19th centuries, Malay literary manuscripts functioned much like scoresheets for a predominantly oral culture of memorisation and recitation. Manuscripts would be passed around at reading assemblies, or majlis pembacaan, where the texts would be recited aloud, ensuring a wider reach to both literate and illiterate audiences.4 In this way, the text is preserved, firstly, in the individual reader-reciter’s memory and, secondly, as part of social memory.

New Masters, New Work Values

Initially, Malay scribes were employed in royal courts to compose epistles in fine calligraphy. Such employment or receipt of royal patronage accorded the scribes regular salaries and a special status in society. Although scribes could be employed by private individuals, religious centres and royal courts were the key producers of manuscripts. The insertion of foreign powers in this region as colonial masters from the 16th century onwards brought about complex changes to the sociocultural fabric of the indigenous populations.

With the arrival of the English and Dutch powers, Malay scribes found a new employer in these colonial parties, particularly towards the 19th century. Aside from official correspondence, British scholar-administrators would employ scribes to copy manuscripts for the purpose of their own study of the Malays – a practice that was emulated by the Dutch. Soon, the two powers competed with each other to acquire Malay manuscripts, creating their commercial value as collectibles. Interestingly, a substantial number of Malay manuscripts, dating mostly to the 19th century, exist in collections held in Leiden, the Netherlands, and other centres outside of the Nusantara.

The Malay Scribe’s Invisible Hand

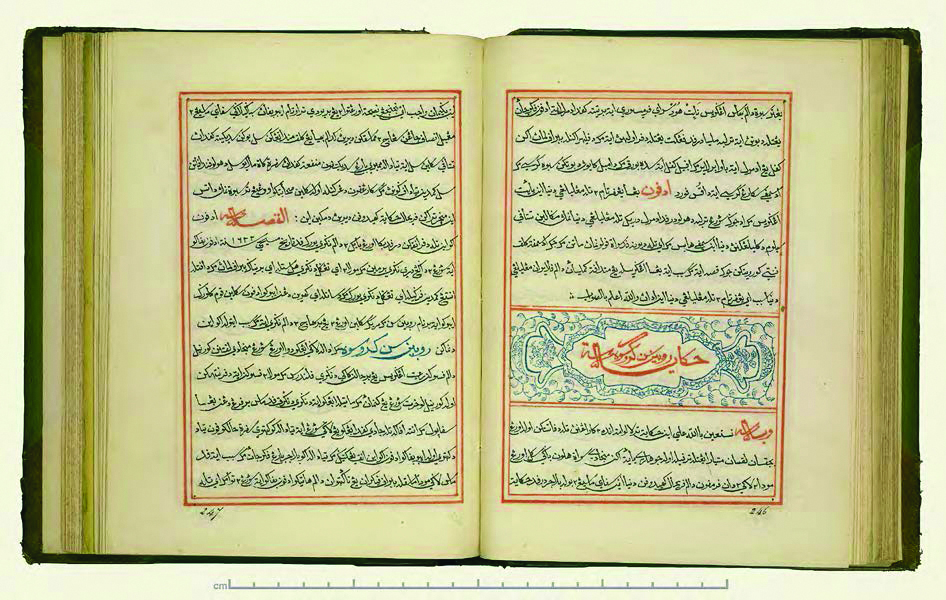

The Malay manuscript tradition underwent its greatest change at the height of colonialism in the 19th century as the Europeans paid more attention to the manuscripts as objects rather than to their content. Consequently, more and more manuscripts included colophons (sections containing either biographical information such as the scribe’s name, the date of the manuscript’s completion and/or the name of the commissioning party) where previously they were not attributed to specific authors or scribes. Instead, Malay manuscripts were regarded as a form of shared heritage belonging to the community-at-large.

Despite this anonymity, colophons were added to the manuscript either at the beginning, end or sometimes weaved into the main text (particularly with the syair form, a traditional Malay rhymed narrative that is sung aloud to a fixed melody). These comment on when and how a manuscript was written, thus rendering visible the often laborious process of copying visible and providing some clues to the scribe’s personality. The end colophon of the Hikayat Abu Nawas states its completion on a Saturday in the Islamic month of Zulhijjah, without providing the year, in the vicinity of Sungei Kallang (Kallang River).

Faithful Copies: An Exception to the Rule

The introduction and subsequent adoption of Islam by Malay rulers from the 13th century onwards stimulated a new avenue of output for the scribes. Furthermore, a core injunction for all Muslims to read the Quran encouraged literacy for all instead of earlier precepts of literacy being reserved for the noble and priestly classes. Islamic texts were written/translated into Malay to provide guidance on the newfound faith of the Malays. Key Islamic tenets such as monotheism differed greatly from the preceding animistic or Hindu-Buddhist beliefs, thus texts explaining and clarifying these newer ideas and principles were essential.

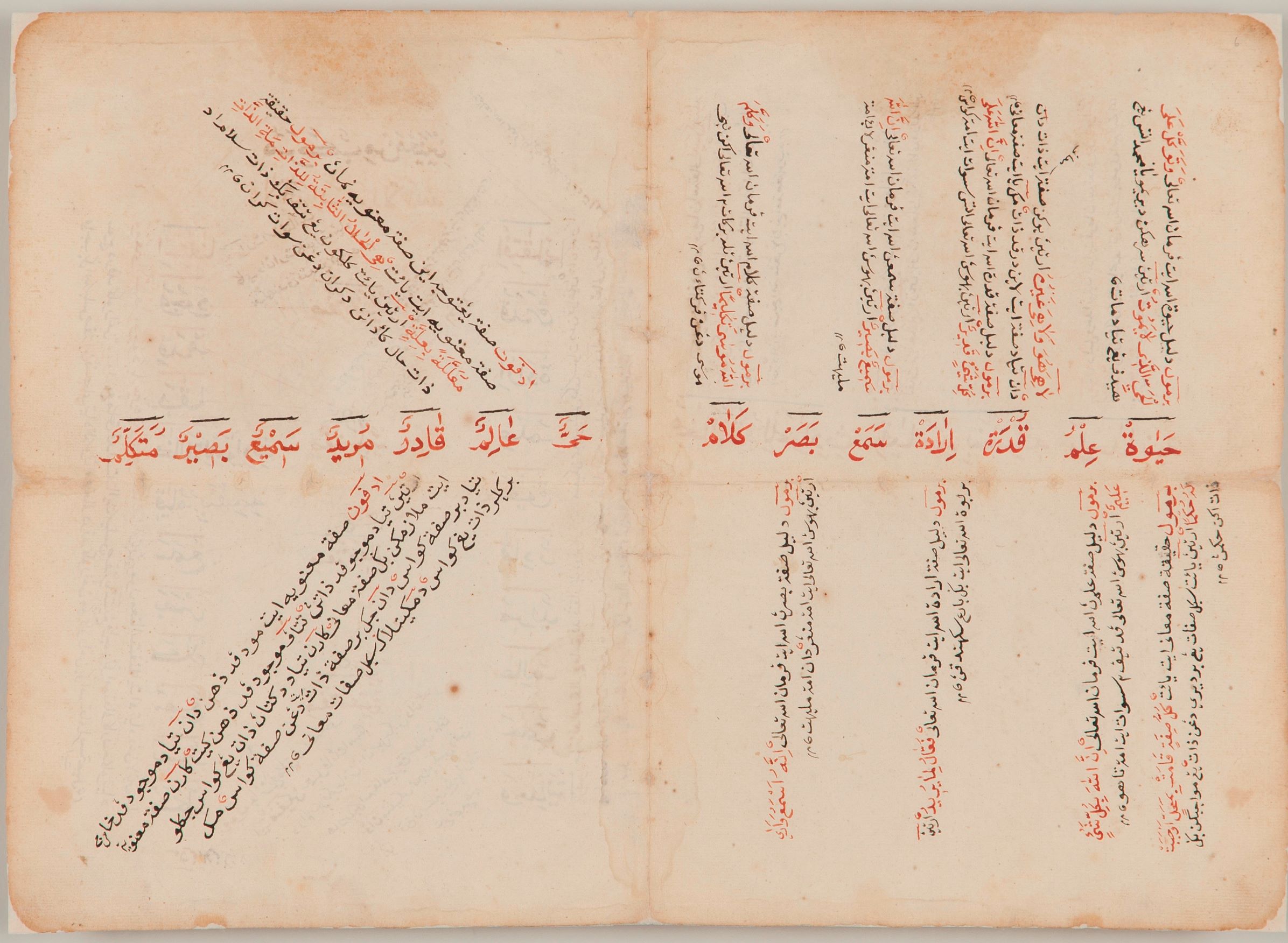

As religious kitab (Arabic for “book”) were regarded as sacrosanct, they were one of the few instances in which a text’s author and the subsequent scribes were clearly attributed so as to establish the authenticity of a text. The importance of naming author and scribe(s) lie in determining the chain of transmission from a religious teacher to his students. Often, such texts were produced under the supervision of a teacher through oral transmission. In some cases, the text had to be retained in its entirety (such as the Quran as the Word of Allah) and original language, Arabic. However, notes could be added to the margins, between lines or any available space around the text, which are often indicative of the scribe’s understanding of the subject matter.

On the Cusp of Mechanised Mass Reproduction

The introduction of mass printing technology in the 19th century threatened to undermine the need for scribes. However, Malay scribes still had one more important role to play, and the demand for their services continued unabated in the early period of Malay printing.

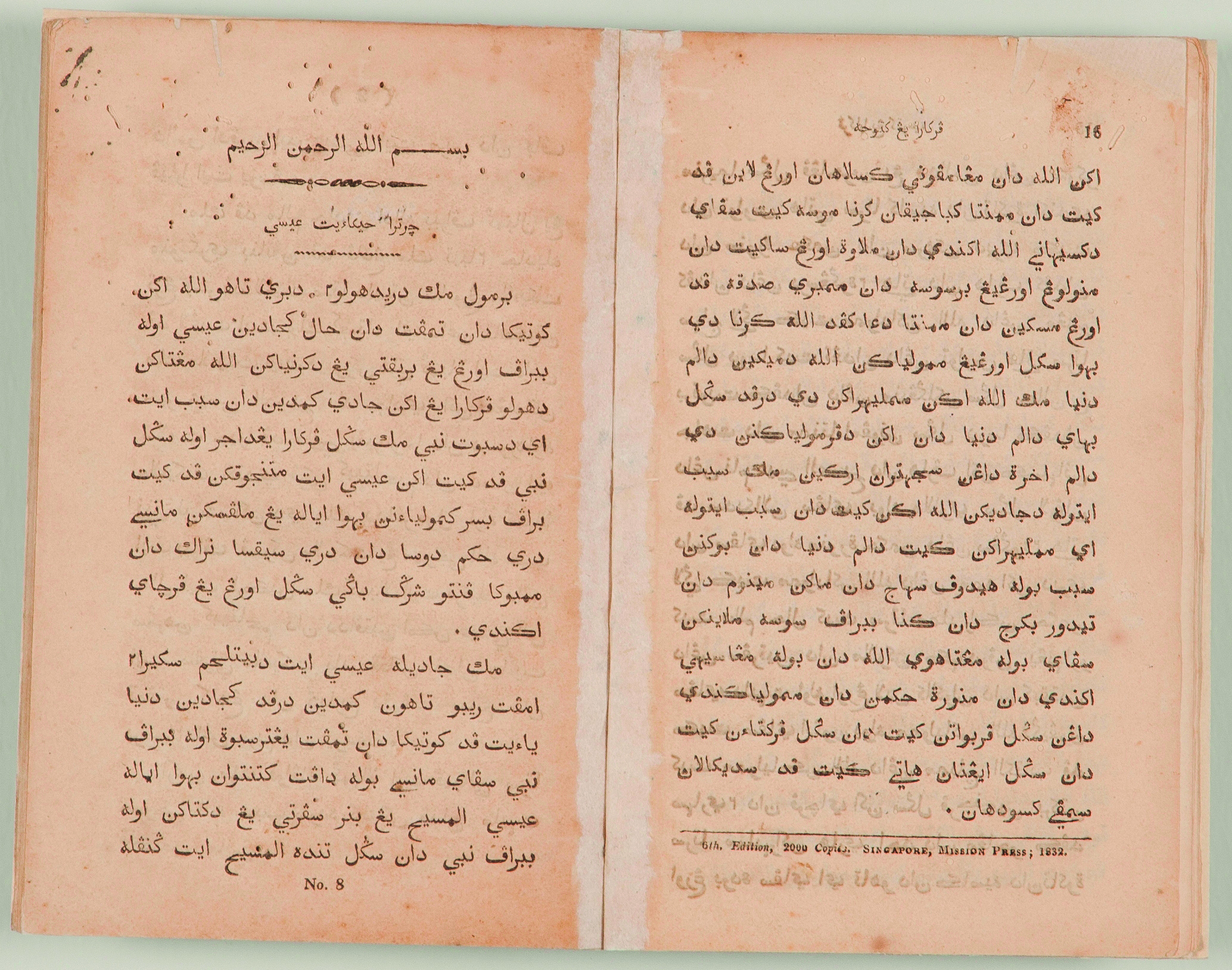

The Christian-based journal, Bahawa hendaklah engkau menyembah Allah dan berbakti kepadanya sahaja, is one of the publications in Singapore that involve Malay scribes as part of the printing process. It also highlights the important role of missionary presses in the emergence of Malay printing in Singapore. The most important was the Mission Press in the hands of Reverend Benjamin Keasberry, who pioneered the use of lithography to reproduce calligraphic styles so that his publications would appeal to a Malay audience familiar with hand-copied manuscripts. In contrast, earlier missionary publications were typographic prints that could not capture the flair and cursive form of handwritten Jawi, with scripts regarded as too uniform and stilted by Malay readers.

In contrast, lithography, called cap batu (stone-stamping) in Malay and favoured by indigenous printers, could convey the grace and fluidity of a scribe’s handwriting. Like copying, scribes would draft a master page on paper that was then etched onto a limestone tablet. The latter acted as a printing plate to reproduce multiple copies of the original hand-composed design. As such, the same scribes with their skill sets could continue to be employed since “a book printed by lithography was essentially a manuscript reproduced”.5

A Mission to Print

For the translation of Christian treatises and other English texts, the missionaries often worked closely with renowned scribe and writer, Munshi Abdullah, who was sometimes termed the “’Father of Malay Printing” as he had imparted lithographic printing knowledge to Malay society.6 In addition to translations, the cooperation between Keasberry and Abdullah in the 1840s and 1850s resulted in multicoloured lithograph editions of Malay texts written, copied and edited by the latter. These editions include Munshi Abdullah’s autobiography, Hikayat Abdullah, published in 1849.7 Keasberry used the proceeds of the press to run a boarding school for boys on River Valley Road. Here, students were taught English and Malay as well as the art of printing, sowing the seeds for the next generation of the Malay publishing industry.

Aside from the missionary presses, colonial regulations in the Dutch East Indies (today’s Indonesia) on local printing and publishing indirectly stimulated the growth of Singapore’s Malay publishing industry. The Reglement on de Drukwerken in Nederlands Indie was issued on 10 November 1856, requiring all printers, publishers and sellers of printed material to apply for licence. In addition, copies had to be deposited free-of-charge with the government. Penalties for violation included confiscation of the publications, shutting down of printing presses, imprisonment and even prohibition from future work as printers or publishers.8 In contrast, the British administration in Singapore enacted less restrictive policies. As a result, many Javanese printers from the Dutch East Indies shifted their bases of operations to Singapore or more specifically, Kampong Gelam. This led to the establishment of the Malay printing and publishing industry in Singapore, which subsequently became one of the major publishing centres in the Nusantara in the 19th and 20th centuries.

“Yang Menulis” (They Who Write) is an exhibition by the Malay Heritage Centre and the National Library, featuring manuscripts from the Library’s Rare Materials Collection. It was first shown at the Malay Heritage Centre from 2 November 2012 to 24 March 2013. It is currently on display (30 March–12 May) at the National Library Building, at the Promenade, Level 7. “Yang Menulis” will also travel to Pasir Ris Public Library (14 May–12 June), Jurong Regional Library (14 June–11 July) and Woodlands Regional Library (13 July–11 August).

Siti Hazariah Abu Bakar graduated from the National University of Singapore with a degree in South Asian Studies in 2011, and is currently a curatorial assistant at the Malay Heritage Centre. Her research interests include the social history of the Malays in Sri Lanka, Tamil Hindu death rituals, Indian Mughal history and Tibetan Buddhism.

Noorashikin binte Zulkifli joined the Malay Heritage Centre in 2010 where she was trained in arts management and interactive media. Noora has been involved in museum work since 2004 and previously worked at the Singapore Art Museum and the NUS Museum.

REFERENCES

Books

Altbach, P.G., & Hoshino, E.S. (1995). International book publishing: An encyclopedia. USA: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Coulmas, F. (1996). The Blackwell encyclopedia of writing systems. Oxford: UK; Cambridge, Mass. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Gallop, A.T. (1994). The legacy of the Malay letter. London: British Library. (Call no.: RSING q899.286 GAL)

Mulaika Hijas. (2011). Victorious wives: The disguised heroine in the 19th century Malay syair. Singapore: NUS Press. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia. (1990). Manuskrip kegemilangan tamadun Melayu: Katalog pameran. [No. 6]. Kuala Lumpur: Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia. (Call no.: Malay 011.31 MAN)

Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia. (2012). The legacy of Malay manuscripts. Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Proudfoot, I. (1993). Early Malay printed books: A provisional account of materials published in the Singapore-Malaysia area up to 1920, noting holdings in major public collections. [Kuala Lumpur]: Academy of Malay Studies and the Library, University of Malaya. (Call no.: RSING 015.5957 PRO)

Ros Mahwati, Ahmad Zakaria & Latifah Abdul Latif. (2008). Malay manuscripts: An introduction. [Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia]: Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia. (Call no.: RSING 091.09595 ROS)

Siti Hawa Haji Salleh. (2010). Malay literature of the 19th century. Malaysia: Institut Terjemahan Negara Malaysia Berhad. (Call no.: RSEA 899.2809034 SIT)

Teo, E.L. (2009). Malay encounter during Benjamin Peach Keasberry’s time in Singapore 1835 to 1875. Singapore: Trinity Theological College. (Call no.: RSING 266.02342095957 TEO)

Articles

Braginsky, V.I. (2002). Malay scribes on their craft and audience (with special reference to the description of the reading assembly by Safirin bin Usman Fadli). Indonesia and the Malay World, 30 (86), 37–61. Retrieved from Taylor & Francis Online website.

Gallop, A.T. (1990). Early Malay printing: An introduction to the British Library collection. Journal of Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 63 (1) (258), 85–124, pp. 97–98. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Proudfoot, I. (1997). Mass producing Houri’s moles or aesthetics and choice of technology in early Muslim book printing. In P.G. Riddell & T. Street (Eds.). Islam: Essays in scripture, thought and society: A festschrift in honour of Anthony H. Johns. Leiden: Brill. (Not available in NLB holdings)

van der Putten, J. (1997). Printing in Riau: Two steps towards modernity. Bijdragen tot de Taal-,Land-en Volkenkunde, Riau in Transition, 153 (4), 717–736. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.