Excavating Women's Participation Within Malaya's Proto=History of Computerisation (1930–1965)

Introduction: The Machine Age

The introduction of mechanised accounting machines in the late 19th century marked a radical break from manual accounting practices. Ranging from punch card readers to cash registers,1 these accounting machines were the ancestors of the modern computer, and constituted a crucial transition stage in Malaya’s technological history.2

From the 1930s to the 1960s, the accounting machine industry in Malaya was dominated by three multinationals, namely the British-based International Computers and Tabulators (ICT) and its American counterparts, National Cash Register (NCR) and International Business Machines (IBM).3 Each of these companies will be examined from three angles: the introduction of their machines, their impact in commerce and government administration, and their employment and representation of women. Collectively, a study of these trends helps to reveal Malaya’s otherwise buried computer proto-history, including a group of unsung pioneers: women operators.

This paper attempts to construct a subaltern gender narrative from the dominant masculinist and Eurocentric infrastructure of transnational corporations, government institutions and commercial media in the first half of the 20th century. Women may have been the first generation of operators, but in official documents and media reports, they were often marginalised. For example, their non-involvement in technological developments was assumed in a Straits Budget report on a talk on post office accounts in 1937: “bookkeeping machines and other electronic accounting devices were demonstrated to the audience, which included non-accountants and women”.4 In published reports, except for a few European women supervisors, the women were nameless. In official photographs, women operators were mostly shown with their backs to the camera or looking away. Such peripheral representations reflected the perceived status of these women operators as the “data proletariat” in a male-led industry. Through assembling these otherwise fragmentary references and images, the three case studies in this paper make possible a more coherent narrative of women’s pioneering participation in Malaya’s data mechanisation and computerisation journey.

“Clever Girls” with the “Queerest Jobs in Town”: The Women Operators of ICT’s Powers-Samas

The first public mention of modern accounting machines came in the 1920s. In 1922, replying to open criticisms of the administrative inadequacies of the Municipality of Singapore by its contracted accountant Major Gooding Field, the Municipal Commission asserted that “cash registers, Burroughs Machines, Amco Adders and Merchant Calculators are in daily use in the Municipal Offices”.5 A decade later, recognising that the bigger and more sophisticated punch card readers could compile and sort larger volumes of data, the Registrar General announced his intention to purchase the “most modern accounting machines”.6 Official records from 1935 show the purchase and installation of a set of mechanised accounting machines for 32,048.07 Straits dollars, together with punch cards (an annually recurring purchase) for 1,783.04 Straits dollars.7 A few years later, a new system was installed; the machines were considered a marvel:

Special cards are punched for each consumer, showing

consumer names and addresses together with their dealings

with the department. These are automatically sorted and

then

run through a tabulating machine which prints the bills, with

duplicates which are bound to form a ledger.8

At that point in the late 1930s, 2,000 out of 40,000 of the Municipal accounts had been mechanised; a full changeover was expected to be completed within a year.9 This initiative was disrupted by the Second World War, and the system reportedly suffered from neglect during the Japanese Occupation (1942–45).10 After the war, the machines were in poor condition. Data collected for the 1947 Pan-Malayan Census had to be reconfigured in Ipoh and sent to be tabulated by the British Tabulating Machine Company in Britain under the control of the Treasury, with the Malayan authorities bearing the cost.11 By 1950, the colony had received a consignment of 15 new machines, valued at £12,000, from the United Kingdom.12 These were to be used – initially alongside their reconditioned older counterparts – to process trade, financial, salary and demographic statistics.13

The new accounting machines were from the Powers-Samas organisation, which was part of the Vickers group of companies that was expanding its operations in Asia through its district office in Calcutta, with a sales and technical service office in Singapore under Henry Waugh and Co. Ltd.14 Following the merger with British Tabulating Machine to form International Computers and Tabulators (ICT) in 1959, the organisation was further committed to the region. In August 1964, ICT installed the Federation of Malaysia’s fourth computer – an ICT 1301 system – in the Public Utilities Board at Singapore’s City Hall, starting the transition out of the old punch card system to a more automated computerised system.15

From the start, the accounting machines did not just facilitate bookkeeping and reports, but also provided new employment opportunities, particularly for women. The participation of this new labour force was initially not welcomed. In 1932, the Singapore Free Press reported on plans to install the Powers-Samas machines in three years’ time. The paper’s comments reflected an underlying anxiety over the accounting machines, and their women operators:

It is understood that a proposal has been made to the Crown

agents to send out about twenty girls with accounting machines

for the Accounts Department of the F.M.S. [Federated Malay

States] Railways. The idea, apparently, is to do away with the

majority of the present staff and train girls for employment.16

Nonetheless, the employment of women proceeded as planned. The Asian women operators, known as clerk-operators, were supervised by Mrs Marjorie Ainger, a European.17 Ainger was the section supervisor from 1935 to 1952, and her principal task was generating the monthly Malayan statistics report.18 Given the general absence of women in public institutions in 1930s Singapore, the mention of Ainger in not only official reports but also newspaper accounts shows the novelty of women in administrative positions.

One of the department’s productions, prepared with the aid of accounting machines, was the Malayan Statistics of Imports and Exports , a 500-page volume with detailed data on diverse categories of transactions. In the 1950s, the machines were operated by 13 women clerk-operators processing close to 50,000 cards each month at a rate of 3,000 cards per hour as part of unit “accounting”.19 As the Singapore Free Press reported,

Surrounded by an array of intricate electrical machines and

working to the accompaniment of weird-pitched, high

sounding clicking noises all day long, these girls do perhaps one

of the queerest jobs in town. But, their job is not only queer; it

is highly responsible.20

The belief was that women were temperamentally more suitable than men as clerk-operators.21

An insight into the early operations of the Powers-Samas accounting machines at the Federated Malay States Railways (FMSR) offices was documented by the Kuala Lumpur correspondent of the Straits Times in 1935. Consisting of five key punching machines, a sorter and a tabulator, the installation was operated by a staff of locally recruited women whom the paper described as “clever girls” who had attained considerable “skill and speed” with only a month’s training. The process generated statistics such as engine types, wagon miles, cargo weight, distance travelled, punctuality, performance, journeys taken by passengers, and storage of goods.

Figure 1 offers a glimpse of the operations of the Powers-Samas accounting machines at the Singapore Statistics Department, which appears to have been staffed entirely by women. In the photo, two operators, with their backs to the camera, have their hands pressed against the machines as they look intently at the paper reels in front of them. Facing them are two other women focused on their machines. Owing to their being featured in local newspaper stories for their work in compiling census data, women became increasingly associated with mechanised data processing in the 1950s and 1960s.22

The supervisory roles in such departments were dominated by European women, even into the 1960s. Like her predecessor Ainger, Joan Talalla started with the Department of Statistics after the Second World War, with 20 non-European operators of accounting machines under her. By 1960, the number had grown to 85, constituting the biggest all-women section within the government.23

The perception of locals being sidelined by colonial racial hierarchies did not go unchallenged, with the tensions being part of the acrimonious industrial relations in Singapore in the 1950s and 1960s. ICT became one of the battlegrounds. On 20 December 1961, 15 workers of ICT who were members of the Singapore Business Houses Employees Union began a sitdown strike to protest against the management’s alleged refusal to negotiate over pay and working conditions, and its deployment of expatriate British staff to maintain operations during the strike.24 As the subsequent case studies of NCR and IBM also show, there was now a growing momentum of knowledge transfer, with more locals being trained and taking on managerial positions as these corporations deepened their engagement with the region.

NCR’s Machine-Conscious Cashiers and Models

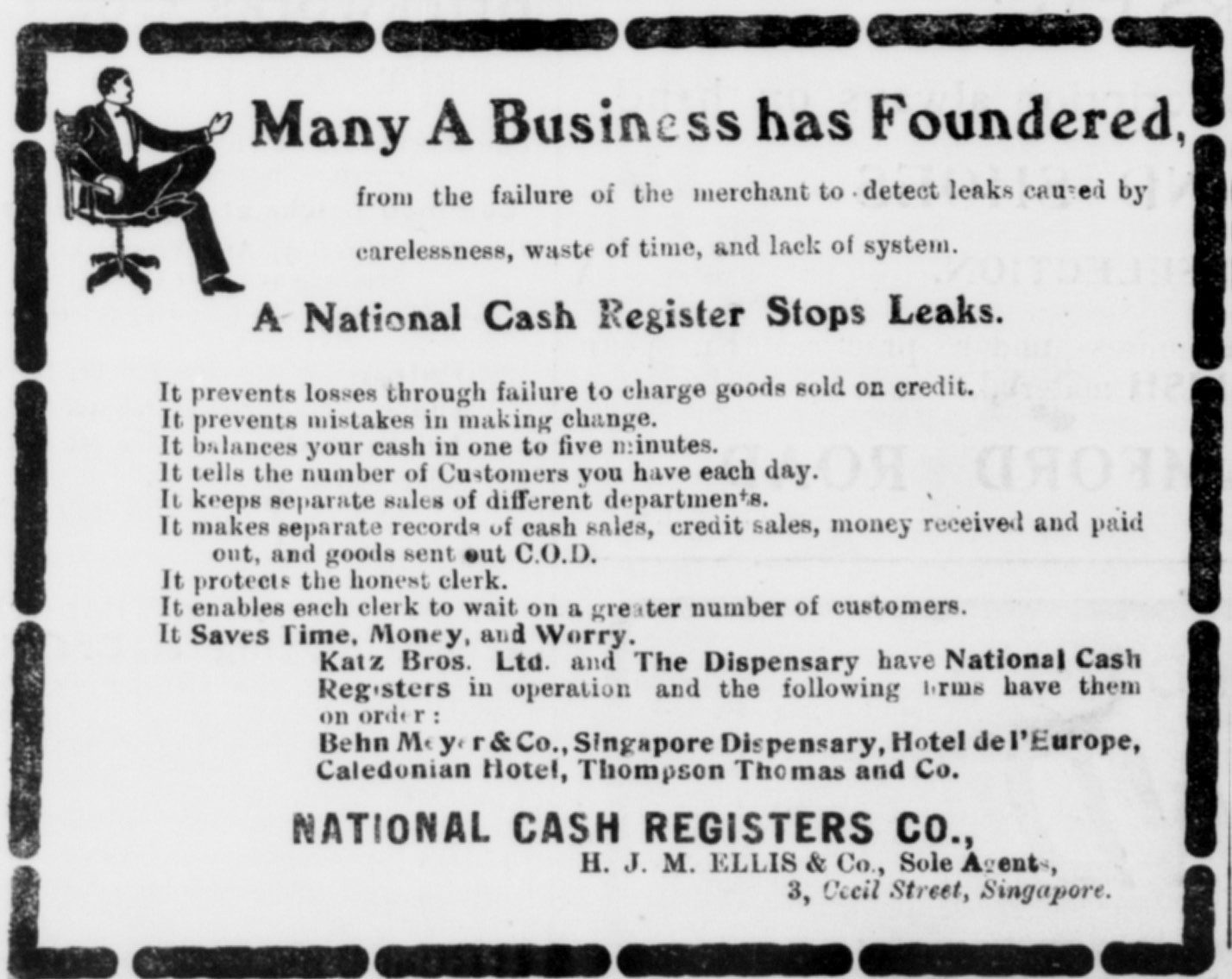

The National Cash Register Company was formally incorporated in Dayton, Ohio, in 1884. Its first advertisement in the broadsheets of British Malaya appeared some two decades later, warning of the problem of inefficiency and theft in manual accounting systems, and promising that “a National cash register stops leaks”.25 This 1905 advertisement in the Straits Times heralded the start of NCR’s marketing and publicity campaign in the region, conducted through the media and public exhibitions.

Up to the Second World War, NCR’s cash registers and accounting machines were distributed by local companies serving as representatives.26 The first NCR branch in Malaya was established in 1950,27and by 1967, there were 12 offices and service depots in Malaysia and Singapore.28 Recognising Southeast Asia’s potential, the multinational positioned Singapore as its regional headquarters.29 NCR attributed the popularity of its products – sales in Malaya quadrupled between 1953 and 1959 – to customers’ new business practices and expectations: “People in Malaya and other Eastern countries are becoming increasingly office machine-conscious. In this atomic age, they want efficiency, speed and accuracy.”30

NCR was active in staging exhibitions to promote both its own machines as well as products that it marketed in its role as the designated local agent.31 Public personalities who visited its exhibitions included Singapore’s first Chief Minister, David Marshall, who was briefed by the corporation’s representatives.32

During this period, NCR machines were installed in some of the city’s major businesses, like Fitzpatrick’s supermarket and the ethnic Chinese-operated Lee Wah Bank,33 heralding a new era of transaction and accounting practices in Singapore. In 1958, the corporation showcased its latest cash register, installed at Fitzpatrick’s, to the Singapore Free Press. Describing it as “speedy and error-free” and a “machine that thinks”, the paper highlighted the convenience of the new registers:

Ordinarily the clerk would be forced to do some swift mental

arithmetic or more likely, use a pencil and paper to figure the

customers’ change […] The latest triumph of the National cash

register over man will relieve operator fatigue and protect the

cashier, who is responsible for the balance in her machine, as

well as the customer. And the cash register, unlike either of

them, is always right.34

Accompanying the story was a photograph of a female Fitzpatrick’s employee seated behind a cash register.

On the media front, NCR was perhaps the pioneer in glamorising and feminising accounting machines in colonial Singapore, as exemplified by a 1957 print advertisement featuring an endorsement of its products by the Sheaffer Pen Co. (Figure 3). The text endorsement was, however, secondary to the image of a Caucasian woman with a broad smile, striking red blouse and neatly permed hair, pulling a printed bill from an NCR accounting machine.

The use of mostly female models in NCR’s advertising campaigns suggests that women dominated the role of operators of its machines. NCR’s advertising momentum continued into its early computer products in the 1960s, with the introduction of its first desk-size computer business system, the NCR 395, to Malaysia and Singapore.35 However, as the next section illustrates, it would be another company, IBM, that truly ushered in the computer age in the region.

From the Beginning: Women and IBM in Singapore

Founded in 1911 as the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company, IBM took on its present name in 1924. It arrived in colonial Malaya and Singapore in 1952 with a staff of three.36 Within a decade, IBM became associated with the first computers installed in the region.37

The use of IBM computers in government departments started in April 1963, probably with the intent of symbolically heralding the formation of the new Malaysian federation comprising Singapore, Sarawak, Sabah and the Federation of Malaya in September.38 A year later, an IBM 1440 was installed at the Lee Rubber Company in Singapore, then the largest exporter of rubber in the world. The company’s extensive regional network of rubber plantations, mills, factories and warehouses was managed by its Singapore headquarters.39

Technological milestones became part of both national pride and industry achievements. Formally launching the Electronic Data Processing unit of the Finance Ministry in 1964, Singapore’s Deputy Prime Minister Dr Toh Chin Chye cited the time savings with the new computer. It reduced the time taken to compile data on voters in the electoral roll from 600 hours to 60 hours. The number of days taken to prepare the payroll of 39,000 monthly rated government employees was also reduced, from 26 days to 8.40

A Straits Times correspondent had earlier described the setup in celebratory and futuristic tones:

In a big air-conditioned office in Fullerton Building, a modern

office is taking shape. An office common to giant commercial

complexes of New York and London. Gone from this office,

eventually will be the normal complement of clerks and typists

Coming into its place: Rows and rows of girls punching holes

on automatic machines-and serving the “brain.” The brain

is an electronic computer just installed in the third floor of

the building for processing accounts and statistics of the

Finance Ministry.41

Around 20 of the unit’s 60 female clerk-operators were already trained to turn “facts and figures into codes” using the new computers, punching around 10,000 holes a day – more than twice as fast as on the dated accounting machines.42 Like their predecessors deployed on the Powers- Samas accounting machines three decades earlier, these women operators were similarly on the frontline of data modernisation.

Figure 4 shows a woman operator demonstrating the IBM computer to Dr Toh at the Treasury in Singapore. The only woman in the photograph, she was probably the lowest-ranked in the group, but her photographic presence gives critical visibility to her generation of computer operators in the region.

Conclusion: Finding the Keypuncher Generation

Beginning as a trickle in the early 1900s with NCR’s cash registers, the diffusion and adoption of mechanised accounting systems in British Malaya gained momentum in the 1930s with the installation of ICT’s Powers-Samas machines. Disrupted by the Japanese Occupation, the pace picked up again in the late 1940s, given the urgent need to restore administration functions, coupled with the new push by American corporations NCR and IBM into the colony’s emerging computer markets.

The proto-history of computerisation in Malaya and Singapore – namely the transition from manual accounting practices to accounting machines

to mainframe computers – has yet to be given detailed scholarly coverage. In this gap lies a hidden history of women operators as frontliners of these new technologies. Gendered perceptions of computer cultures as male undertakings have also been projected onto technological historiographies to assume women’s absence in the field. This paper has shown that women in fact actively participated in Malaya’s proto-history of computers. As operators in each of the successive waves of technological advancement, they may be considered part of the pioneering keypuncher generation – the first data proletariats.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Crystal Abidin, A/P Peter Borschberg and A/P Natalie Pang, as well as staff of the National Library.

Liew Kai Khiun is a scholar of media and cultural studies. This paper is part of

his research on Singapore’s computer history under the Lee Kong Chian Fellowship. His

publications cover historical and heritage studies in Singapore as well as media and

cultural flows in the Asia-Pacific. He is currently an Assistant Professor at Hong Kong

Metropolitan University.

Liew Kai Khiun is a scholar of media and cultural studies. This paper is part of

his research on Singapore’s computer history under the Lee Kong Chian Fellowship. His

publications cover historical and heritage studies in Singapore as well as media and

cultural flows in the Asia-Pacific. He is currently an Assistant Professor at Hong Kong

Metropolitan University.Bibliography

Ang, James and Soh P. H. “The Singapore Government’s Role in National Computerization Efforts.” Behaviour & Information Technology 14 no. 6 (1995): 361–69.

Computer History Museum. “International Computers and Tabulators, LTD. (ICT).” Accessed 20 July 2022.

Goh, Chor Boon. Technology and Entrepôt Colonialism in Singapore, 1819–1940. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2013. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 338.064095957 GOH)

Holt, Natalia. Rise of the Rocket Girls: The Women Who Propelled US, from Missiles to the Moon to Mars. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2016.

IBM. “IBM Archives.” Accessed 29 July 2022.

—. “Singapore Chronology.” Accessed 25 July 2022.

“IBM Hursley Museum.” Accessed 29 July 2022.

Norberg, Arthur L. “High-Technology Calculation in the Early 20th Century: Punched Card Machinery in Business and Government.” Technology and Culture 31, no. 4 (October 1990): 753–79.

Singapore Trade and Industry. Government Statistics. January 1973. Singapore: Singapore Department of Statistics, 1973.

Straits Settlements. Annual Departmental Reports. I.D./74. Singapore: Printed at the Government Printing Office, 1934. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 354.595 SSADR)

—. Blue Book of the Year. Singapore: Government of the Colony of Singapore, 1935. (Microfilm NL3144)

—. Blue Book, I.F. 68. Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1937. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 315.957 SSBB)

Newspaper Articles (From NewspaperSG)

Business Times. “ICL Wants to Make an Impression First.” 5 April 1978, 2.

Eastern Sun. “NCR Makes Singapore Southeast Asia Headquarters.” 29 September 1966, 3.

—. “Page 1 Advertisements Column 2.” 14 November 1967, 1.

Malaya Tribune. “National Cash Register Agency.” 11 May 1914, 10.

—. “Municipal Accounts: Replies to the Statement Made by Major Field.” 26 August 1922, 7.

—. “Page 11 Advertisements Column 4.” 31 March 1950, 11.

Singapore Free Press. “13 Girls Record Singapore’s Trade.” 15 April 1947, 5.

—. “100 European Women Hold Government Posts.” 22 May 1948, 1.

—. “More Know How to Read, Write.” 10 October 1949, 5.

—. “Statistics Work to Be Speeded Up.” 3 July 1950, 5.

—. “Cash Register Checks All the Book Work.” 30 September 1955, 3.

—. “Enter the Mechanical Brain.” 11 August 1958, 20.

—. “Mechanisation.” 5 November 1959, 10.

—. “Lee Wah Bank – The First to Bring You the Wonder of Electronic Banking.” 23 May 1960, 9.

—. “Two More Ultra-Modern Buildings Going Up in Malaya.” 23 May 1960, 9.

Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser. “Brighter Accounting: Girls for F.M.S. Railways Department.” 11 January 1932, 8.

—. “Colonial Secretary: Change in Budget Procedure.” 25 September 1934, 3.

—. Untitled. 23 October 1935, 11.

—. “Municipal Accounts Now Compiled by Machinery.” 24 July 1939, 7.

Singapore Standard. “Marshall Sees New Machines.” 5 October 1955, 10.

—. “On the Feminine Front.” 26 May 1957, 15.

—. “These S’pore Women Can Tell You Plenty.” 7 July 1957, 4.

Straits Budget. “$9 Million in F.M.S. Savings Bank: Intricacies of Post Office Accounts.” 25 November 1937, 10.

—. “Machines Will Check Census,” 20 February 1947, 16.

—. “What Mr. Statistics Said Was: Women Are Better Than Men Only at Monotonous Work.” 3 February 1960, 3.

Straits Times. “Page 4 Advertisements Column 1,” 24 March 1905, 4.

—. “Mechanised Accountancy in Malayan Offices.” 8 September 1935, 18.

—. “New Machine System for Municipal Accounts.” 24 July 1939, 13

—. “The Municipality in the Machine Age.” 18 September 1948, 9.

—. Koh, Philip, “The Machine Age Replies.” 25 September 1948, 9.

—. “‘Back Room Girl’ for U.K.” 16 May 1951, 7.

—. Liau, Nyuk Oi. “Personalities Behind the Machines.” 16 July 1951, 8.

—. “Machines Step Up Work.” 24 August 1951, 4.

—. “Page 8 Advertisements Column 1.” 29 February 1952, 8.

—. “Business Statistics in Minutes on New Accounting Machine.” 25 September 1953, 10.

—. “Accounting Machines Sales Drive.” 19 November 1954, 12.

—. “Company Has New Colony Offices.” 8 March 1955, 12.

—. “Page 14 Advertisements Column 1.” 18 February 1956, 14.

—. “National Cash Register Display.” 10 October 1958, 4.

—. “Company Quadruples Sales in 6 Years.” 30 October 1959, 10.

—. “She Rules Kindly in Women-Only Domain.” 5 October 1961, 16.

—. “A New Sit-Down Strike Begins.” 21 December 1961, 4.

—. “End to 82 Days Strike.” 15 March 1962, 5.

—. “IBM High Speed Computer Coming.” 28 December 1962, 16.

—. “Statistics Department to Use Computers.” 26 April 1963, 14.

—. “IBM Units in CPF Office.” 8 October 1963, 12.

—. “Mighty ‘Brain’ Goes to Work.” 20 January 1964, 4.

—. “Singapore Efficiency Admired, Says Dr. Toh.” 7 March 1964, 4.

—. “NCR’s Latest in Electronic Accounts.” 7 July 1964, 12.

—. Lim, Peter. “Enter Mr. Superthink.” 11 October 1964, 1.

—. “ICT Forms Far East Region H.Q.” 5 August 1966, 12.

—. Kwee, Masie. “About Brains That Drain and Those That Remain.” 25 July 1971, 18.

—. “A Monument of Local Business Success.” 27 November 1971, 32.

Straits Times Annual. “Page 64/65 Advertisements Column 1.” 1 January 1906, 64.

Sunday Tribune. “Savings Banks Officials Ready to Handle Any Amount of Business: $30,000 Accounting Machines Arrive.” 10 August 1947, 2.

NOTES

-

Arthur Norberg, “High-Technology Calculation in the Early 20th Century: Punched Card Machinery in Business and Government,” Technology and Culture 31, no. 4 (October 1990): 753–79. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

The only recognisable form of the chronology of data processing technologies came during the installation of the first modern computer systems at the Central Provident Fund offices to compute pension statistics in 1963. See James Ang and P. H. Soh, “The Singapore Government’s Role in National Computerization Efforts,” Behaviour & Information Technology 14, no. 6 (1995): 361–69. ↩

-

Peter Lim, “Enter Mr. Superthink,” Straits Times, 11 October 1964, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“$9 Million in F.M.S. Savings Bank: Intricacies of Post Office Accounts,” Straits Budget, 25 November 1937, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Municipal Accounts: Replies to the Statement Made by Major Field,” Malaya Tribune, 26 August 1922, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Colonial Secretary: Change in Budget Procedure,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 25 September 1934, 3 (From NewspaperSG). See also Straits Settlements, Annual Departmental Reports, I.D./74 (Singapore: Printed at the Government Printing Office,1934), 38 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 354.595 SSADR). However, Chief Accountant P. H. Forbes stated that accounting machines were introduced into the Chief Accountant’s department in 1933. “Mechanised Accountancy in Malayan Offices,” Straits Times, 8 September 1935, 18. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Straits Settlements, Blue Book of the Year (Singapore: Government of the Colony of Singapore, 1935), 100. (Microfilm NL3144) ↩

-

“New Machine System for Municipal Accounts,” Straits Times, 24 July 1939, 13 (From NewspaperSG). The maintenance fees for the accounting machines were 1,285 Straits dollars a year. The purchase of cards (including freight) for these machines in 1927 cost 3,072.26 Straits dollars. Straits Settlements, Blue Book, I.F. 68 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1937), 106. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 315.957 SSBB) ↩

-

“Municipal Accounts Now Compiled by Machinery,” Singapore Free Press and the Mercantile Advertiser, 24 July 1939, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Savings Banks Officials Ready to Handle Any Amount of Business: $30,000 Accounting Machines Arrive,” Sunday Tribune, 10 August 1947, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Machines Will Check Census,” Straits Budget, 20 February 1947, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Statistics Work to Be Speeded Up,” Singapore Free Press, 3 July 1950, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Until the North Borneo Census in 1951, the Malayan Department of Statistics at Singapore’s Fullerton Building did not have sufficient accounting machines after the Second World War to process the information, and the data had to be sent to London for analysis and compilation. “Machines Step Up Work,” Straits Times, 24 August 1951, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Accounting Machines Sales Drive,” Straits Times, 19 November 1954, 12 (From NewspaperSG). Powers- Samas Accounting Machines Limited (1929) was the renamed British company, Power Tabulating Machine Company, formed in 1915. It subsequently merged with its competitor, British Tabulating Machine Company (BTM), to form International Computers and Tabulators (ICT) in 1959. “International Computers and Tabulators, LTD. (ICT),” Computer History Museum, accessed 20 July 2022. ↩

-

Lim, “Enter Mr. Superthink.” ↩

-

“Brighter Accounting: Girls for F.M.S. Railways Department,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 11 January 1932, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ainger was appointed on 5 October 1935 as Lady Supervisor, Powers-Samas Installation, Department of Statistics, Straits Settlements and Federated Malay States. “Untitled,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 23 October 1935, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Following Ainger’s retirement in 1952, a job advertisement was placed for a replacement with the responsibility of supervising the preparation of reports by the Powers-Samas punch card systems as well as the operation of the machines. With a salary range of $420–$620 per month, the advertisements also stated a preference for “females between the ages of 30 and 40 years” and “satisfactory educational background”. “Page 8 Advertisements Column 1,” Straits Times, 29 February 1952, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“13 Girls Record Singapore’s Trade,” Singapore Free Press, 15 April 1947, 5 (From NewspaperSG). Details on these operators were available in job advertisements after the Second World War, which indicated significant increases in the qualifications of candidates, the scope of responsibilities and the remuneration. A short paragraph in an advertisement in 1950 only mentioned the salary of $70 per month as well as preferably Cambridge certification. “Page 11 Advertisements Column 4,” Malaya Tribune, 31 March 1950, 11 (From NewspaperSG). Six years later, a lengthier paragraph detailed the requirements of residency status as British subjects, prior experience operating the Powers-Samas machines, as well as possessing a “Standard VII” educational background. The salary range had also increased to $137–$197 per month. What remained unchanged was the requirement for applicants to be females below the age of 25. “Page 14 Advertisements Column 1,” Straits Times, 18 February 1956, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Mechanised Accountancy in Malayan Offices,” Straits Times, 8 September 1935, 18 (From NewspaperSG). The Straits Times feature on these operators revealed their allocations in several areas: receiving cheques and forms, punching cards, verifying and sorting printed bills. Liau Nyuk Oi, “Personalities Behind the Machines,” Straits Times, 16 July 1951, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

See: David Gabriel, “These S’pore Women Can Tell You Plenty,” Sunday Standard, 7 July 1957, 4; “What Mr. Statistics Said Was: Women Are Better Than Men Only at Monotonous Work,” Straits Budget, 3 February 1960, 3; “She Rules Kindly in Women-Only Domain,” Straits Times, 5 October 1961, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“She Rules Kindly”; Joan Talalla was the wife of the war-time flying ace Jimmy Talalla. “On the Feminine Front,” Singapore Standard, 26 May 1957, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A New Sit-Down Strike Begins,” Straits Times, 21 December 1961, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Page 4 Advertisements Column 1,” Straits Times, 24 March 1905, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

NCR cash registers were first marketed together with other American products under Ellis & Co. in the 1900s. “Page 64/65 Advertisements Column 1,” Straits Times Annual, 1 January 1906, 64 (From NewspaperSG). One of the distribution agents in the 1910s was the Wadleigh Company, set up in 1914 to “deal principally between rubber planters in Malaya and the consumers in New York”. This suggests that there was demand in the rubber industry for such machines. “National Cash Register Agency,” Malaya Tribune, 11 May 1914, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Company Quadruples Sales in 6 Years,” Straits Times, 30 October 1959, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Page 1 Advertisements Column 2,” Eastern Sun, 14 November 1967, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

NCR had already set up a data processing centre in Singapore in 1964; at the time of the announcement, it was awaiting the arrival of its NCR 315 computer for the new computer centre. “NCR Makes Singapore Southeast Asia Headquarters,” Eastern Sun, 29 September 1966, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Company Quadruples Sales in 6 Years”; “National Cash Register Display,” Straits Times, 10 October 1958, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Marshall Sees New Machines](https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/singstandard19551005-1.2.144.4),” Singapore Standard, 5 October 1955, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Two More Ultra-Modern Buildings Going Up in Malaya,” Singapore Free Press, 23 May 1960, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Enter the Mechanical Brain,” Singapore Free Press, 11 August 1958, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Costing $250,000, the NCR 395 was claimed to be able to perform multiple computer functions and print 40 percent faster than conventional electronic machines. “NCR’s Latest in Electronic Accounts,” Straits Times, 7 July 1964, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore Chronology,” IBM, accessed 25 July 2022. ↩

-

“Company Has New Colony Offices,” Straits Times, 8 March 1955, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

With the installation of the IBM 1401 computer, and subsequently the ICL 1903A, came the creation of a new Computer Services Department under the Ministry of Finance. Known initially as Electronic Data Processing, the department provided statistical data processing facilities to the Statistics Department and related units in various government ministries. “Singapore Efficiency Admired, Says Dr. Toh,” Straits Times, 7 March 1964, 4 (From NewspaperSG). Such machines in turn generated a larger volume of reports and official publications, including monthly and annual reports on national statistics. In addition, the department also provided accounting services on projects on payrolls, registers, school examination results and recruitment. Singapore Trade and Industry, “Government Statistics,” January 1973 (Singapore: Singapore Department of Statistics, 1973), 54–55. See also: “Statistics Department to Use Computers,” Straits Times, 26 April 1963, 14; “IBM Units in CPF Office,” Straits Times, 8 October 1963, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Weighing 10 pounds (4.5 kg), the 14-inch (36 cm) portable “discpack magnetic memory device” was able to store several million characters with information retrievable and compiled from typing the required items from a linked typewriter. “IBM High Speed Computer Coming,” Straits Times, 28 December 1962, 16 (From NewspaperSG). (I would like to thank Dr Loh Kah Seng for posting this reference publicly on his Facebook account.) The corporation revealed that the rental and maintenance cost of the system alone amounted to around $10,000 a month. This did not include expenses from electricity charges and salaries. Lim, “Enter Mr. Superthink.” ↩

-

“Mighty ‘Brain’ Goes to Work,” Straits Times, 20 January 1964, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩