Public Bathing in Singapore, 1819–1942 Cultures, Landscapes and Architecture

The east is essentially a land of bathing. The white man tubs

himself, the yellow man, the brown man and some of the black

men rub themselves – with water. The remainder prefer oil.

The first question a white man asks on arrival is “Have you a

swimming bath?”1

Introduction

With 26 public pools across the city, complemented by pools of private clubs and residences, Singapore residents today have no shortage of access to water for recreation and sport. This wider access to swimming is often traced back to the opening of Mount Emily Pool in 1931, placing Singapore’s history of leisure swimming as a phenomenon of the 20th century.2 The first municipally owned site for swimming, Mount Emily Pool arguably represents the point when swimming became truly public. It was part of a wider programme of the Municipal Commissioners, who were beginning to see public recreation as part of their remit, thus representing an important transition from older laissez-faire models to a modern one of government provision.3 However, the attention given to Mount Emily Pool, which highlights public swimming, also masks a longer history of popular swimming in Singapore that extends to the early 19th century.

Although swimming environments prior to Mount Emily Pool were not public in the current sense, there have nonetheless been places for popular swimming in Singapore since at least the 1820s, more than 100 years before the opening of Mount Emily Pool. My aim here is to extend the accepted timeframe of public swimming by sketching an initial history of the wider social and physical environments of swimming in colonial Singapore. It begins with the origins of British colonialism and ends with the Japanese Occupation.

Several histories have addressed swimming in Singapore, but none cover this extended period. Ying-Kit Chan wrote a significant study of swimming in relation to Singapore’s politics, though focused on a postcolonial setting.4 Jocelyn Lau and Lucien Low recorded the popular memory of a large collection of pools, and other detailed histories have been written about individual swimming clubs.5 Most often, references to the local history of swimming are minor parts of wider sports histories, including those of writers such as Nick Aplin and Peter Horton, who reasonably focus more on the development of athletic sporting pursuits.6

My intention, however, is to document a wider view of swimming, not just as sport or exercise, but as a series of interconnected social practices based around designated swimming sites. To piece together this history, I worked with various primary sources at the National Library and National Archives of Singapore, combining passing details from newspapers, maps, reports, photographs, travel memoirs and other materials, to build an initial picture of the development of popular swimming practices and locations across the 19th and early 20th centuries. These record the environments of early swimming, and the debates surrounding them.

Based on the period of British colonialism in Singapore, this history is very much about how British administrative views shaped local ideas on swimming and bathing. It is about how a new geography of bathing was established within the colony through definitions and limitations of water use. As such, I do not discuss the bathing practices that originated from Singapore’s precolonial settlements. The chosen time period traverses the introduction of Singapore’s public water system, addresses how Victorian morality met colonial racism, and considers how bathing transformed from personal respite to communal leisure, and then to sporting exercise.

19th-Century Swimming

Various types of aquatic leisure environments have been available and popular in Singapore since the early period of British settlement. These have included pagar (fenced sea enclosures), bathing piers and swimming tanks, which are the predecessors of today’s Olympic-standard pools. However, it is not always straightforward to bring these examples together and suggest them as sources of contemporary swimming approaches.

The problem in extending histories of swimming to the 19th century lies in historical language, and the common practices and understandings then. What we today recognise as “swimming” – an athletic activity with fixed strokes and distances – did not exist for most of the 19th century. As Nick Aplin indicates, 19th-century swimming was more a social activity, which although allowing for community games, was not really a sport yet.7 The term “swimming” in its present sense was not even applicable then. Based on its use in 19th-century newspapers, people in Singapore only “swam” when fleeing sinking ships or escaping pirates.8 The word was not applied to a leisurely dip in the water, instead suggesting emergency crossings of water, which were certainly not perceived as recreational. Leisurely forms of going into the water were understood as “bathing”.

The use of the word “bathing” does raise complications, particularly for its association with hygienic forms of washing, which are very distinct from what we now consider “swimming”. However, these two approaches to entering the water share common historical roots that combine leisure and cleansing, and are described in several histories of bathing, including the classic work of architecture historian Sigfried Giedion.9 In the 19th century, swimming and washing were still largely unified activities; people bathed for many reasons: exercise, recreation, socialising, hygiene and sometimes even games or competition. Water-based competitions were launched at the New Year Sports Day and events such as the opening of the New Harbour (Keppel Bay), and public lectures and the popular press gave advice about the general health benefits of sea swimming, as well as warnings of the dangers of bathing as exercise.10

This distinction of historical language is useful, as it helps to map a series of interconnected activities that sets the scope of this initial history. Based on this language, my approach has been to incorporate the period’s wider sense of “bathing”. Therefore, I combine recreational swimming, public washing, socialising in the water, and the gradual emergence of water-based athletics, considering the design of the physical locations that allowed these varied activities to take place. My intention is to make sense of how water access was mapped onto Singapore’s landscape within the British colonial system. Essentially, this is to consider how people could access water, what kinds of structures provided this access, and how water bodies were classified for public use. Official efforts to define public bathing resulted in special designations of urban water bodies, mapping the town’s water according to allowable practices within the colonial system. It was through these designations that modern ideas of water use emerged, leading to new definitions of swimming and its separation from washing and domestic bathing.

An Imported Bathing Culture

The British arriving in Singapore from 1819 brought with them their own ideas about public bathing. It was only since the beginning of the 19th century that sea swimming became popular, as British culture turned away from older inland springs and spas and found the pleasures of the seashore.11 As Ian Bradley demonstrates, European spas had developed as sites for healing, where people might take part in practices of balneotherapy and hydrotherapy,12 and later became spaces for leisure and indulgence.13 As bathing in the sea grew in prominence in British culture, it also adopted these mixed uses, being seen at times as a place for health, but also as a place for recreation and pleasure. Over time, the same mixed purposes transferred onto the pool, the tank and the tub.

European sailors arriving in Singapore encountered a tropical and at times oppressive heat, as well as year-round warm waters, and they were clearly interested in bathing in the sea. From the 1820s, they often dove into the harbour waters beside their ships both to clean themselves and to enjoy the water, in a practice known as “bathing ship-side”. The early press advised against this activity given the potential dangers of drowning or being taken by a shark, and some did die while bathing ship-side.14 The warnings reduced the practice for a time, but it would return and the warnings resumed. From the recurring press warnings, it seems that bathing ship-side in open water continued throughout the 19th century.15

But it was not only transient sailors who wanted to swim; European residents of the town also wanted to enjoy the seaside and began planning their own recreational space. Early in 1827, a group gathered to fund a beachside bathing enclosure. In May that year, the Singapore Chronicle reported on the newly finished pagar at the Esplanade, below what was then the town’s second battery, next to the mouth of the Bras Basah River.16 This was colonial Singapore’s first swimming structure, and its first designated recreational space, arriving two years before the formation of the Billiards Club in 1829, which Walter Makepeace regarded as the town’s first sporting club.17

As described in the Singapore Chronicle, the battery pagar directly fronted the Esplanade beach. Along the shore, it comprised three walls of nibong palm poles enclosing a swimming area of 65 m by 65 m.18 Above the farthest wall from the shore were dressing rooms, suggesting a pier along one side allowing swimmers to access them. This approach of placing dressing rooms over the water followed contemporary European practices and resembled early “bathing machines” – portable cabins that could be wheeled into the water.19 This approach was defined by contemporary European concepts of morality and decency, where bathing clothes were viewed as a state of undress, and therefore no one wanted to be seen publicly in such an immodest state. Dressing rooms directly over the water allowed the least amount of time that a person could accidentally be seen improperly dressed. The location of this pagar would later be called Scandal Point, and while that name emerged for different reasons, we might imagine the original “scandal” of this place as the undressed bodies of bathers.

The author of the original description of the battery pagar considered its architectural style to be “somewhat rude”, and thought the dressing rooms too high above the water.20 However, they otherwise considered the structure perfectly adequate, hoping its establishment would provide a place for public bathing for years to come. The “rudeness” of the enclosure most likely refers to its regional vernacular construction. The battery pagar

appears to have used conventions of Malay and Orang Laut architecture, which remained the dominant architectural style for Singapore’s pagar over the following century. A very similar construction style was still used for enclosures of the 1920s and 1930s, shown in images of military bathing enclosures (Figure 1), and described by Bob Pattimore in recollections of the pagar at the tin smelting works on Pulau Brani.21 The key elements were a fence for protection, a place to dress, and a pier to access the water.

The original pagar at the Esplanade did not last long. Only one further reference to it was made in the press, at the start of 1828, when a convict was accidentally killed by a police officer while bathing there.22 There is no record of how or why the battery pagar was removed, though it is quite possible that it collapsed in a monsoon, as happened with similar structures later in the century.23 Though it was short-lived and quickly forgotten – later discussion of early bathing made no mention of it – the structure of the pagar, as a typology of leisure architecture, remained much the same for more than a century.24

A Series of Short-lived Establishments and Failed Plans

After the battery pagar, there were no immediate attempts to build new facilities for bathing. It was reported in 1846 that a committee was formed to build a new bathing pagar at the Esplanade, but it was not realised.25 A new enclosure was finally built in 1849, called Marine Villa, at the end of Telok Ayer Road.26 Throughout the 19th century, bathing places (as with any other recreational activity) were expected to be products of private interest, formed as social clubs or as businesses. Marine Villa was a business, charging ten cents for entry; it opened two days a week for families, and one day for single men. Marine Villa probably did not last long – it was last mentioned in the press in 1850.27

In the mid-1860s, there were two further attempts to establish formal bathing sites. One was another business venture at Orchard Road, catering to nearby residents. For this, W. R. Scott had a freshwater pool, “a large swimming bath built of brick and stone, surrounded with a high brick wall”, built on his Abbotsford estate, which he opened to the European public in 1866.28 However, according to C. B. Buckley, it was not used very much and only lasted a year.29 Around the same time, Singapore’s first swimming club was founded in Tanjong Rhu. After an initial meeting, Charles Crane was assigned to organise the place, overseeing the construction of a new pagar on the east coast. According to Buckley, the enclosure was built on a sandbank away from the shore.30 The club continued for a couple of years, but dissolved when the pagar was destroyed in a monsoon. In the 1870s and 1880s, a series of indoor bathhouses were opened. In the town, Gazzolo & Co. was on North Bridge Road, and the Waterfall Club opened at the foot of Pearl’s Hill.31 For those who could spend a couple of days in the countryside, there was the Tivoli Bathhouse in Bukit Timah.32

None of these sites were longstanding establishments, but the intermittent appearance of bathing places does show growing interest in public bathing. The number of bathing places grew after 1867, when the Straits Settlements became a colony separate from India. As Mary Turnbull described, this was a period of economic growth when European settlers began demanding something more from their place of residence – wanting to develop the town, making it physically more impressive, and providing greater recreational spaces.33 The problem faced by early bathing sites – the reason they closed so quickly – seems mostly to have been financial. Bathing architecture required significant upfront costs for construction, and the resulting attendance was just not enough to support the costs of maintenance.

The lack of bathers to financially support bathing sites was not a sign of limited interest in the water, but rather a product of the social structures of bathing within British colonies. Generally, the mixing of races and sexes in bathing sites was not allowed – the majority of the formal bathing sites mentioned above were made for European men, which comprised a minuscule part of Singapore’s overall population. Furthermore, the places also had to compete for the men’s time with a range of other sporting and social clubs, which as John Butcher has shown, formed the primary setting for European social lives in the British colonies of Southeast Asia.34 Marine Villa did offer family days, which meant that European women and children could also swim, and the Waterfall Club was one of the few sites that provided for both European and Asian bathers, with separate rooms and bathing tanks.35 Racial segregation in bathing continued into the 1960s, though in more popularly accessible places like the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) Pool it had disappeared by the 1920s. Separated bathing based on sex continued well into the 20th century, and the Mount Emily Pool ran a schedule offering different times for men and women bathers up until the beginning of the Japanese Occupation (at which point, the Japanese authorities that reopened the pool in 1942 maintained a similar schedule).36

As people tried to establish swimming clubs and bathhouse businesses, particularly from the 1870s onwards, newspaper letter writers complained about the lack of recreational bathing options. Some insisted (contrary to the historical evidence) there had never been an established place for bathing in Singapore, and that if towns like Penang, Shanghai and Hong Kong had their own baths, then surely Singapore must as well.37 They also insisted that bathing would surely make a good business, calling on some enterprising resident to step forward. One writer, perhaps seeing little other option, even had the audacity to volunteer Cheang Hong Lim to extend his philanthropy and build a public bath.38

These exaggerated remarks help prepare an image of the kinds of recreational bathing environments people wanted. These letter writers in the late 19th century were usually driven by concerns of safety and decency, much like the group who made the battery pagar in 1827. They wanted fenced enclosures to protect themselves from sharks, and changing rooms or a fenced screen to protect their modesty. Over time, they began asking for additional conveniences, like placing the pagar farther out to sea so tidal patterns would not dictate bathing times.39 They preferred an easily accessible central location, often proposing the beach at the Esplanade as the most ideal site.40 These suggestions centred around similar ideas for public bathing, shaping wider discussion and informing the more substantial proposals for swimming that emerged later in the century.

What followed were defined proposals for ambitious popular bathing structures, which went unbuilt. In 1889, the Rowing Club developed plans for a large pool on the Raffles Reclamation ground, in front of the Raffles School.41 The plan fell apart because of its grand scale: it required excavation, construction of a concrete pool, and the creation of a sluice system that would allow the pool to be filled with seawater and drained for cleaning. Combined with their proposal for a clubhouse, the scheme just became too expensive for the club to pursue. As the Rowing Club gave up on its plans for swimming, in 1891 a private individual, W. A. Wafford, went to the Straits Legislative Assembly with two proposals for bathing sites: a floating bath moored off Johnston’s Pier, or a piled enclosure built off the Esplanade.42 The Assembly rejected both, because the former would interrupt boats, and the Assembly would not privatise the Esplanade – the most prominent public place in the town – or risk spoiling its views.

In 1893, the Singapore Swimming Club was established in Tanjong Katong,43 largely putting an end to the ongoing discussion among European residents about the need for bathing sites. However, one further proposal for floating baths off the Esplanade was put to the Municipal Commissioners in 1900.44 They refused to consider it as their jurisdiction did not cover the sea.

The clubs, pools, pagar and bathhouses discussed in this section have been focused on European residents’ views of aquatic leisure, with most built and proposed examples seemingly created only for Europeans. So far, I focused on tracing the development of formal bathing sites built as commercial enterprises for leisure, none of which were particularly successful. But this was not the only way people engaged with the pleasures of bathing in the 19th century.

Practical Bathing for the Public

Running parallel to the history of European bathing ventures in colonial Singapore was an imposition on the poorer strata of society of the same values of security and modesty that were so important to the letter-writers and builders of early pagar. This occurred as Singapore’s municipality began developing its own plans for the uses of town waterscapes. Writers in the press launched attacks on people bathing publicly, protesting the sight of bodies in various states of undress, or that of men and women bathing together.45 Apart from some cases of naked European sailors at remote beaches,46 there was frequently a racial tone to such complaints.

Given that the Singapore press of the time was primarily British, the key concern with public bathing was often that white women might happen to see degrees of exposed brown skin in public spaces. Writers complained about Chinese men washing in back lanes, Malays in canals, and Indian men in the Bras Basah River at Dhoby Ghaut.47 Dhoby Ghaut was especially a concern when the Ladies’ Lawn Tennis Club opened there in 1884 as a venue for the wives of members of the Cricket Club, even though the place had long been known as a place for washing and working in the river.48 Just as earlier European bathers wanted to shield themselves from public view through screens and changing rooms that entered directly into the water, they hoped these public washing spaces might also be shielded from view, if not removed completely.

The municipality responded by building attap screens and small enclosures around common bathing spots at public wells or riversides. One of the earliest was made in 1849 around a well in Telok Blangah, opposite the Temenggung’s palace, in what was reported as a great cleaning and

beautification of that town.49 This approach continued (Figure 2), though as the Municipal Commissioners gained greater power to organise the urban environment, they could begin designating fixed bathing places, and making bathing in other places a chargeable offence.50 Through this came a process of classifying town water spaces, determining the allowable functions of urban water bodies.

A moral concern over bodily exposure was partly what influenced the restricting of water sites, but the process was also part of the commissioners’ broader concern for disentangling the town’s water and waste systems to improve public health. As the Municipal Commission worked to establish Singapore’s reservoir system in the 1860s and 1870s, they also classified water according to social and economic functions. Bathing needed to be restricted in places where water was used by commercial boats or was a drinking source. This eventually led to the municipality’s closing of contaminated public and domestic wells to prevent disease, but had the effect of further limiting people’s access to water.51 As part of limiting the “nuisance” of public bathing, the Municipal Commissioners also placed criminal charges on people found bathing naked in public sites, ensuring that bathing and washing would always be decent and modest activities.52

Regulation created a classification of water spaces according to understood functions, but rules were often subverted by the public. The Impounding Reservoir (MacRitchie), which was obviously intended for piped town water, was where many people saw prime opportunity for bathing – a chargeable offence. One European man bathing there tried to escape the charge by claiming he was simply retrieving his hat that had blown into the water. The fact he was completely undressed and likely in the company of two Japanese prostitutes did not help his defence.53

Gradually, these rules about recognised bathing places led to concerns in the Municipal Commission over the broader working-class public’s access to water and washing.54 And even where there was access, there remained problems with the water’s cleanliness. For example, in the mid-1870s there were reported to be 42 designated bathing places along the Singapore River and its adjacent canals, even though the river was the most polluted water body in the town.55 And so, the municipality tried a new strategy. Instead of just demarcating allowable bathing places in public water bodies, they would build their own new places with different water sources. These had an affordable one-cent entry fee, provided clean water, and encouraged good hygiene. A trial was built on the Singapore River behind the Ellenborough Market in 1874, and since this was before the reservoir was finished, clean water was brought in by water boat.56 Being placed at the market, it was hoped this bathhouse might become an established social centre for nearby residents.

When the municipality’s Impounding Reservoir was completed in 1877, the new infrastructure allowed a rethinking of public bathing provisions. In 1880, the Ellenborough Market bathhouse was redesigned by Municipal Engineer Thomas Cargill to use cleaner municipal water.57 Cargill finished another bathhouse on Boat Quay in 1881.58 These places were enclosed wooden buildings, with tiled roofs, taps and iron tanks made to hold a communal bath, and as pieces of municipal architecture they received a positive reception:

If we may judge by the tasteful and convenient erection over

the Singapore River beside Boat Quay, the movement of the

Municipal Commissioners in putting up bathing houses

in various parts of the town is not only a step in the right

direction, but one calculated to provide ornaments to the place.

The substitution of tastefully designed buildings for the former

rough plank partitions, and the interior arrangement of a large

oblong tank, supplied with water from the waterworks, is at

once such a vast improvement upon former constructions as

to awaken admiration of the taste and ability of the Municipal

Engineer, and the public spirit of the Commissioners, in

providing such elegant public conveniences.59

A third bathhouse was built at the Clyde Terrace Market on Beach Road, and a fourth negotiated with the Tanjong Pagar Dock Company (which then was not part of the Municipality60), but there is no reference to any finished structure in that place.61 the municipal bathhouse programme did not progress beyond this point, and those that were built disappeared by the mid-1890s, with declining attendance and rising maintenance costs.62 The growing acceptance of piped domestic water had changed social practices of gaining access to water, and by this point more people simply bathed at home. To some extent, the municipal bathhouses of the 1880s bridged the town’s attitudes to changing models of water supply, which placed central importance on the new reservoir. This is despite, as Brenda Yeoh has discussed in detail, the new reservoir system’s inability to produce enough water for the growing town, which among other responses, led the Municipal Commissioners to become particularly concerned with prospects of water wastage at their bathhouses, while continuing to close groundwater wells on grounds of contamination.63

The municipal bathhouses provided popular access to freshwater bathing, but they were controversial: some residents rejected the idea of paying an entry fee to access a resource that had previously been free in domestic wells. Even so, many other sanctioned bathing places of the older model remained free, such as the popular Rochor Canal and Dhoby Ghaut.

Recreational Swimming at the Turn of the Century

Even if there could not be enough formal bathing venues to meet public demand, people still found places to go into the water. This was through sneaking nighttime swims at the Esplanade, visiting Beach Road, or travelling to rural beaches at Pasir Panjang, Tanjong Katong, Siglap or Changi.64 All of these were popular places without any of the architecture of bathing; and as places of recreation they appealed equally to European and Asian residents. The east coast, later a centre for swimming, was already known for bathing trips as early as the 1850s.65 Ultimately, bathing was an opportunistic activity – people bathed wherever they found water, whether in the sea, rivers, canals, ponds, quarries or, in a couple of accounts, monsoon-struck fields.66

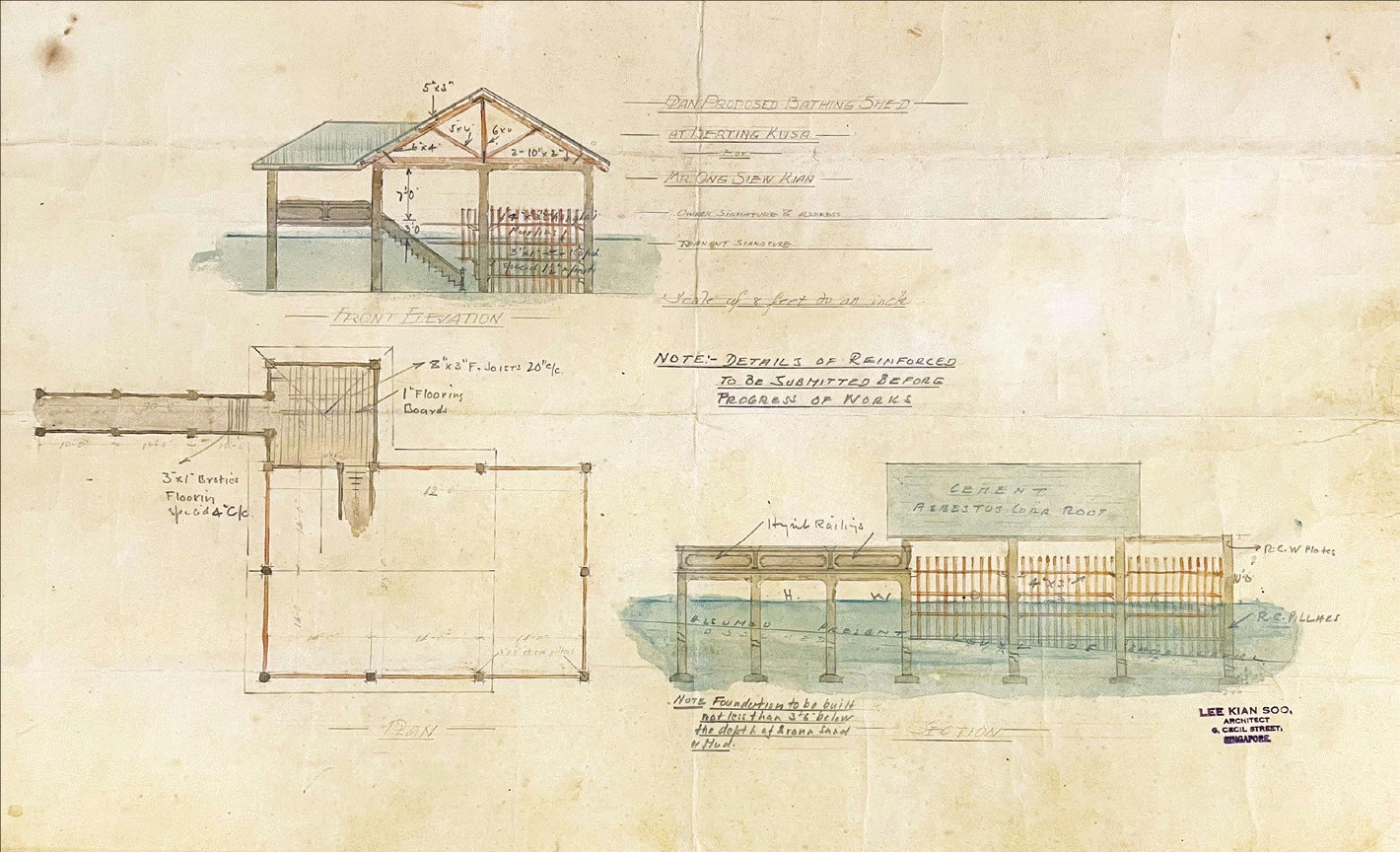

Over time, people built holiday homes along the coasts, following the enjoyable places for beach swimming and defining the areas of Singapore’s future suburban expansion. They moved to Pasir Panjang and Tanjong Katong, places that provided access to the beach, and bathing activities were gradually formalised through the design and construction of personal piers, bathing rooms and pagar. For the wealthy, bathing in the sea was always available, and this developed a coastal architecture of swimming that emulated at smaller scale the ambitions of larger bathing schemes. Figure 3, for example, shows a private pagar, designed by the architect Lee Kian Soo for Ong Siew Kiam in Kampong Beting Kusa, a coastal village near Changi, sometime in the 1920s. The structure included the conventions of old bathing enclosures, while making use of modern construction. Its posted fence resembled the old nibong palm structures of earlier pagar, while using concrete foundations to secure the enclosure. Lee created a pier from the shore, leading to a swimming area in deeper water, which was half-covered with asbestos roofing to protect swimmers from the sun. The structure was more refined than earlier built examples, though it ultimately followed conventions of bathing architecture that had been in place since 1827.

It was during this period, as ambitions of recreational bathing moved beyond town limits, that two new bathing clubs were established. Both managed to survive and become Singapore’s premier institutions for swimming: the Singapore Swimming Club, founded in 1893, and the Chinese Swimming Club, which was fully formed as a social club about 15 years later.67 Both clubs have received substantial historical description from club historians, who discuss their individual developments,68 but what is necessary here is to consider the significance of these lasting clubs within the larger history of Singapore’s bathing cultures. Arguably, the greatest success of these places, and what marks them as different from earlier clubs, is that both embraced an open model that was rejected by earlier planners, thus avoiding the financial trap of older bathing places and ultimately allowing them to survive. Both avoided the expensive, complicated and yet preferred locations of the town, choosing instead to reside in the rural east coast. This drew criticism from some, who found accessing these places inconvenient,69 but they were nonetheless places already popular among swimmers for half a century.70

Both clubs were founded to enjoy the pleasures of sea bathing, and neither chose to build a pagar, deciding instead to make use of open beaches. They put their money into renting (and eventually buying) beachside houses that were used for dressing rooms and dining areas. At first, their distance from the town meant that these places could only be used during weekends. The Singapore Swimming Club established a regular sampan launch from Johnston’s Pier on Sundays to help members reach their site, which was not accessible by road until 1907.71 The early Chinese Swimming Club (then the Tanjong Katong Swimming Party) rented out its clubhouse through the week to families wanting a short retreat in the countryside, thus subsidising its rent.72 These approaches differed significantly from the largescale proposals of the 1880s and 1890s, and arguably allowed both clubs to survive and gradually build membership. It took six years for the Singapore Swimming Club to invest in any form of bathing architecture, deciding

in 1899 to build a sea platform for members’ aquatic play – providing a chute, diving platform and swinging rope.73 The platform gave swimmers a destination, a capacity to exit the water and dive back in. The structure was the centrepiece in one of C. Jackson’s 1914 illustrations for Our Singapore, an image that presents the swimming club as a place of relaxed recreation: drinks by the sea, reclining in the sun and playing in the water.74 This sense of pleasure was the image of coastal bathing at the start of the 20th century, and as the clubs grew in popularity, residents along the east coast built their own piers, bathing rooms and swimming structures, placing the clubs within a rural landscape of beachside pleasure architecture (Figure 4).

The Singapore Swimming Club catered only to Europeans, and the Chinese Swimming Club served Straits Chinese residents. These became the centres of popular swimming in the first two decades of the 20th century. And even if some complained about their distance from town,75 they largely ended the 19th-century press complaints about Singapore’s lack of bathing places. The racial divide between the clubs also placed them as the last vestiges of Singapore’s colonial laissez-faire and communitarian model of recreation, where each social group was expected to establish its own recreational organisations. But the clubs also began to represent changes in bathing practices, drawing attention to an emerging sporting element by holding swimming races and forming water polo teams. For some club members, bathing was starting to turn into an athletic and competitive activity, but this was still not the dominant paradigm.76 In the 1920s, bathing as a sport was to develop elsewhere.

Bathing for Recreation and Sport

In 1919, the YMCA received permission to take over one of the old reservoir tanks on Fort Canning, which they proceeded to turn into a 36-metre saltwater pool.77 This helped the club pursue its international ambition to promote physical education.78 The YMCA was, of course, just another private club, but its wider social mission gave this pool a broader public reach. As a result, the YMCA’s Fort Canning Pool became Singapore’s most significant bathing place for establishing a modern and public swimming culture. The YMCA was instrumental in teaching swimming skills to a wider population, as well as promoting sporting and competitive attitudes to bathing. From the early 1920s, the YMCA taught swimming to boy scouts, girl guides and local schoolchildren.79 Their Physical Director, J. W. Jefferson, visited the Chinese Swimming Club, instructing swimmers in sporting strokes and setting the path for the club to produce some of the strongest competitive swimmers of the 1920s and 1930s.80 In 1920, the YMCA established an annual swimming competition that was open to any member of the public,81 opened the Fort Canning pool to students during school holidays82 and organised events for the public to swim in designated social groups.83 These activities expanded public knowledge of swimming, and drove its popularity.

The 1920s and 1930s then saw major growths in the creation of bathing architecture, with bathing increasingly moving inland. The success of the YMCA Pool was partly the reason for this, but the new structures were also a response to contemporary international fashions for swimming. Swimming was modern and desirable, as the fashionability of suntans among Europeans made sunbathing appealing, and new sartorial ideas drove interest in the parade of novel and glamorously designed bathing suits.84 Contributing to the social demand for swimming environments, new methods in water engineering promised sanitary pools through oxidising filtration systems and chemical cleaning.85

In Singapore, attitudes to open-sea bathing turned negative in 1925 when Doris Bowyer-Smyth, a young socialite from Sydney, was killed by a shark at the Singapore Swimming Club.86 A wave of recognition about the dangers of open swimming followed, and people became hesitant about swimming without enclosures. While the successes of the Singapore Swimming Club and Chinese Swimming Club came from letting go of 19th-century expectations of bathing in pagar, in public opinion this was no longer an option – an architecture of bathing was necessary. Quickly after Bowyer-Smyth’s death, the Singapore Swimming Club built an enclosure.87 In following years, others were built at the Chinese Swimming Club, the Sea View Hotel and private homes along the east coast.88 The military followed, building enclosures at their bases in Sembawang, Seletar and Changi (see Figure 1).

As enclosed sea swimming continued to be seen as a necessity, the growing trend of swimming led some inland clubs to fund the construction of their own pools. The Swiss Club built its pool first, followed by the Tanglin Club.89 The new Golf Club that emerged from the municipality’s closure of the old Racecourse proposed to include a pool as well.90 These were European clubs, and Aw Boon Haw recognised the lack of equivalent recreational spaces for the Chinese middle classes. He decided to establish his own recreational club on the coast of Pasir Panjang in 1930, which included a saltwater swimming pool and pagar that could hold a thousand people.91 The military again followed suit, building pools on bases in the 1930s, not long after having built their seaside enclosures. However, the military had long held interests in bathing for recreation, building tanks in forts as early as the 1860s as a healthy option for recreation that would deter soldiers from engaging in Singapore’s vices.92

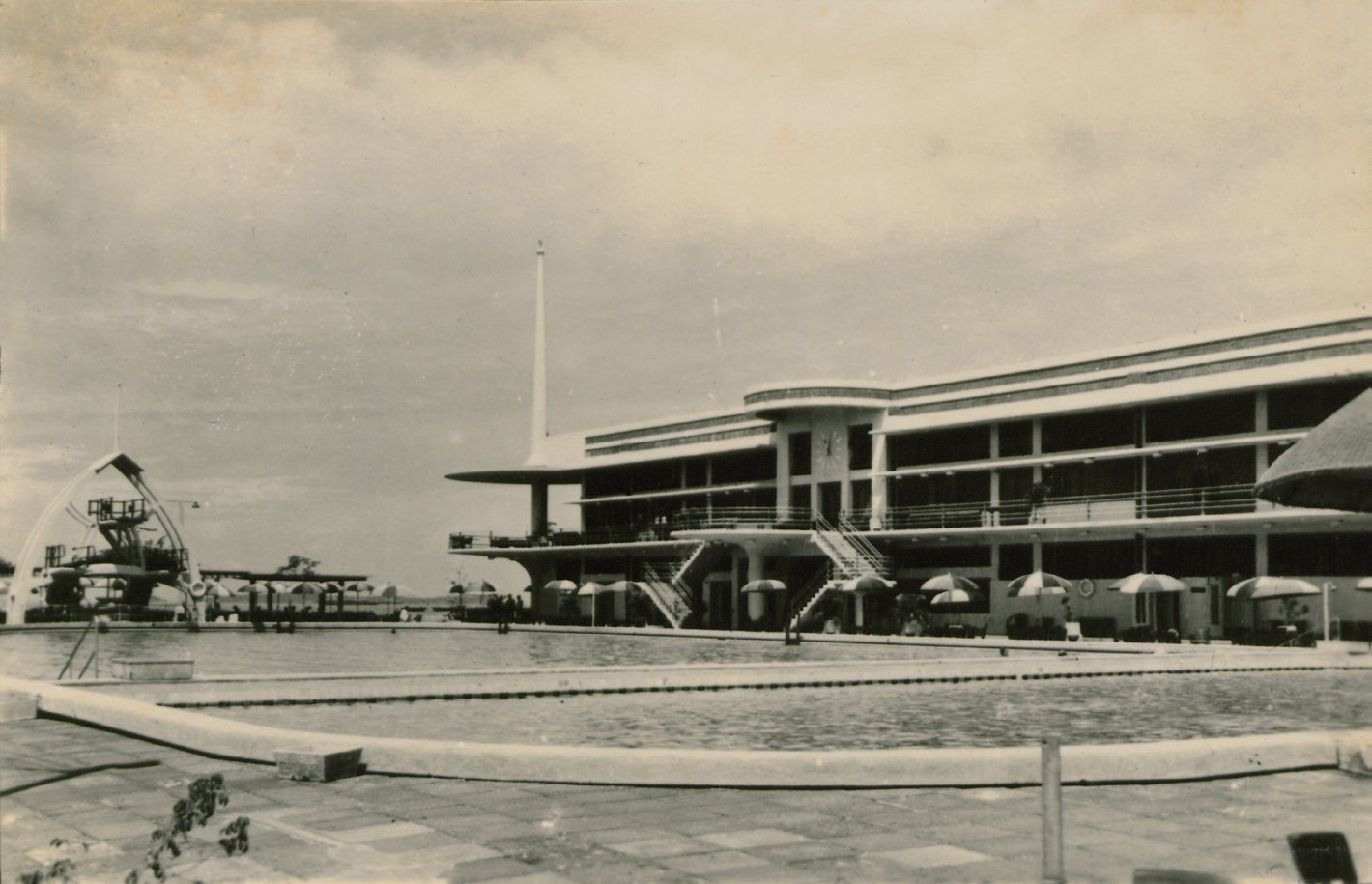

Possibilities for recreational bathing were growing rapidly; in certain respects it seemed like the old centres of bathing and the east coast swimming clubs were falling behind through their attachment to the sea. It was this pressure to keep up with other clubs and retain their premier position that led them to invest in their own pools. The Singapore

Swimming Club considered building a pool from 1928,93 but also debated moving to a new site at Tanjong Berlayer on the west coast.94 Eventually they decided to retain their Katong site and build an inland pool, which opened in 1931.95 Four years later, they added a modern clubhouse designed by the architect Frank Dowdeswell that proved to be a spectacular example of streamlined modernism (Figure 5).96 With graceful horizontal lines and curved corner balconies, this building was at the forefront of worldwide interest in fashionable leisure environments. In the 1930s, the club was at the height of fashion. As Bruce Lockhart wrote in 1936:

[S]ince my time there has been a boom in bathing. Indeed,

on a Sunday the scene at the Singapore Swimming Club pool,

fenced off from the sea and said to be the largest in the world,

is an unforgettable sight. The costumes of the women lose

nothing by comparison with those of Paris Plage and Deauville,

and iced-beer softens the rigours of sun-bathing.97

The Chinese Swimming Club followed this example, redeveloping their site to build a new clubhouse and a pool known as the Lee Kong Chian Swimming Pool in 1938.98 The new designs created by the swimming clubs, as with the inland European social clubs, embraced the visual language of modern architecture. They left behind the old vernacular of Singapore’s swimming places, and established a new image of leisurely swimming environments that embraced modern concrete construction, new technologies, and the graceful sweeping lines of modernist and streamlined architecture.

With the developments in recreational bathing occurring in the private clubs, the municipality took notice. At this time, the municipality was developing ideas about public provision of recreation that radically differed from their predecessors. They began seeing it as part of their remit to provide leisure and health spaces for the public, which included the creation of new sports fields.99 Public interest in swimming was obvious, and they made plans for municipal swimming places. This led to the Mount Emily Pool, which was modelled on the YMCA Pool at Fort Canning. To create this first public pool in 1931, the municipality used a similar strategy of repurposing old water infrastructure, converting one of the tanks of the Mount Emily Service Reservoir into a freshwater pool.100 Aside from the YMCA Pool, this strategy was also used earlier in a private pool at Keppel Hill, owned by the Tanjong Pagar Dock Company, where a reservoir built in the 1890s was converted to a company pool sometime in the 1920s. At this time, the municipality also provided new bathing options by creating the Tanjong Katong Pagar, near the Singapore Swimming Club, which extended public access to the seashore.

The 1920s and 1930s were a period of transition when new swimming options opened up, bringing a much larger public to the water. These decades saw a restructuring of recreational bathing into athletic swimming, as more people learned to swim in fixed strokes and were encouraged to take part in competitions, largely prompted by the YMCA. New seaside and inlands baths were formed, including a diversity of saltwater, freshwater, chemically treated and filtered-water swimming options, each providing different swimming qualities. By this point, swimming was an entrenched element of private clubs and had become a service provided for the wider public. The surging interest in swimming, and the successes of the YMCA and the Chinese Swimming Club in international competitions, such as the Far Eastern Olympic Games in Shanghai in 1927 or inter-club competitions abroad,101 led to the foundation of the Singapore Amateur Swimming Association in 1939.102 This organisation brought together private and military clubs and began a process of regulating swimming as an athletic activity in Singapore, eventually leading to swimmers competing in the Olympics as “Singaporeans” after the Second World War.103

The symbolic ending of this period of growth in bathing came in 1941. By the end of the 1930s, the east coast was dotted with piers and bathing structures. The British military demolished all bathing structures along the east coast as they mistakenly expected that this area would be the focus of Japanese invasion.104 In the early 20th century, the growing popularity of bathing led to it becoming solidified in architectural interventions; in 1941, these physical demonstrations of new attitudes to leisure and hygiene were removed, but of course, the interest remained, and was ready to inform the creation of new swimming places after the war.

Conclusion: Mapping Urban Waterscapes

In this initial history of public bathing in colonial Singapore, I have combined ideas of bathing for leisure, health and cleanliness to consider the methods and varieties of places through which people entered the water in public environments. In extending Singapore’s history of bathing a century before the 1931 origins of municipally owned public swimming at Mount Emily Pool, a key task was to begin identifying the places of bathing.

Figure 6 maps the locations of bathing places within the town of Singapore, including pagar, pools and bathhouses that were built by the municipality, clubs and private business owners. This is in addition to known designated bathing sites in natural water bodies, although these kinds of washing sites largely remain undocumented and the map represents only a limited view. The map also includes proposed bathing sites, showing how the urban landscape in terms of water access, recreation and public hygiene was interpreted then. The proposals and activity were concentrated around the government district, especially the Esplanade and Fort Canning – the former being Singapore’s premier social centre, and the latter a centre of official activity. The flourishing of bathing activity and construction, however, was because most of these places within the municipal area did not last very long. The proliferation of urban bathing places in the 19th century did not represent a thriving culture of bathing but the desire for one; each place responded to the lack of available bathing options.

Outside the town were many more sites for bathing, including the Abbotsford Pool, the Tanglin Club and the Chinese Swimming Club. Despite being harder to access, built bathing sites in the countryside often lasted longer than their urban counterparts, though this reflects their often institutional nature, such as those managed by the government, the military and the Tanjong Pagar Dock Company. Institutional pools catered to groups who were required to live and work outside the town, offering an outlet for recreation. Outside the town, bathing cultures became truly established, as people travelled to rural beaches, built piers and bathing rooms at country homes, and eventually founded lasting swimming clubs.

In the 19th century, bathing places were products of private and institutional interests in health and leisure. They included places designed for recreation, such as military swimming tanks or the earliest swimming clubs, as well as those sites designated for personal washing, like municipal bathhouses. By the early 20th century, a more defined culture of bathing was developing, and as provision of the municipal water supply expanded, public bathing focused in creasingly on recreational and sporting sites, since

personal washing was becoming a domestic activity. As interest in bathing solidified, a more refined architecture of seaside pagar and inland pools developed, establishing recreational and sporting cultures of swimming that, after the Second World War, became models for Singapore’s modern ideas of sport and public leisure. However modern the interest in swimming in Singapore might seem, it undoubtedly dates back to cultural interests in bathing that were defined by British arrivals in the early 19th century, which resulted in early practices of ship-side bathing and the initial construction of the battery pagar in 1827.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Bruce Peter for his helpful comments on the manuscript, Tomris Tangaz for her support in conducting this research, and Nadia Wagner for encouraging me to study histories of swimming in the first place. Thanks also go to staff at NLB who supported me in this work, in particular Joanna Tan, Makeswary Periasamy and Soh Gek Han.

Bibliography

Aplin, Nick. “The Rise of Modern Sport in Colonial Singapore: The Singapore Cricket Club Leads the Way.” In The Routledge Handbook of Sport in Asia, edited by Fan Hong and Lu Zhouxiang, 190–205. New York: Routledge, 2021. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 796.095 ROU)

—. “Sport in Singapore (1945–1948): From Rehabilitation to Olympic Status.” International Journal of the History of Sport 33, no. 12 (2016): 1361– 79.

—. Sport in Singapore: The Colonial Legacy. Singapore: Straits Times Press, 2019. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 796.095957 APL)

De Bonneville, Francoise. The Book of the Bath. New York: Rizzoli, 1998. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RUR 391.64 BON)

Bradley, Ian. Health, Hedonism and Hypochondria: The Hidden History of Spas. London: Tauris Parks, 2020.

Buckley, Charles Burton. An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore 1819– 1967. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 BUC-[HIS])

Butcher, John G. The British in Malaya 1880–1941: The Social History of a European Community in Colonial South-East Asia. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1979. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 301.4512105951033 BUT)

Chan, Ying-Kit. “‘Sports is Politics’: Swimming (and) Pools in Postcolonial Singapore.” Asian Studies Review 40, no. 1 (2016): 21.

Cheong, K. L. and Chia K. Y. “Early Years.” In The Chinese Swimming Club Souvenir 1951, 15–28. Singapore: Chinese Swimming Club, 1951. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RUR 797.2106095957)

Chinese Swimming Club (Singapore). The Chinese Swimming Club Souvenir 1951. Singapore: Chinese Swimming Club, 1951. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RUR 797.2106095957)

Copping, Lynne. Life on Pulau Brani, letter from Bob Pattimore. Singapore Memory Project. Accessed 15 June 2023.

Ferguson, A. Extracts from the Sanitary Report of the 2nd and 4th Batteries 17th Brigade Royal Artillery, Stationed at Singapore, from the 15th September to the End of the Year 1863. London: n.p., 1863.

Gagan, J. A. The Singapore Swimming Club: An Illustrated History and Description of the Club. Singapore: Times Printers, 1968.

Giedion, Sigfried. Mechanisation Takes Command. New York: Oxford University Press, 1948.

Gray, Fred. Designing the Seaside: Architecture, Society and Nature. London: Reaktion, 2006. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART 720.941 GRA)

Horton, Peter. “Singapore: Imperialism and Post-Imperialism, Athleticism, Sport, Nationhood and Nation-building.” International Journal of the History of Sport 30, no. 11 (2013): 1221–34.

Jackson, C. Our Singapore: Sketches of Local Life. Singapore: n.p., 1914. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.57 JAC)

Lau, Jocelyn and Lucien Low, eds. Great Lengths: Singapore’s Swimming Pools. 2nd ed. Singapore: Kucinta, 2017. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 797.20095957 GRE)

Lee, C. Q. “25 Years of Progress and Expansion.” In The Chinese Swimming Club Souvenir 1951, 29–32. Singapore: Chinese Swimming Club, 1951. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RUR 797.2106095957)

Lindley, Kenneth. Seaside Architecture. London: Hugh Evelyn, 1973.

Lockhart, R. H. Bruce. Return to Malaya. London: Putnam, 1936. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5 LOC-[ET])

Makepeace, Walter, Gilbert E. Brooke and Roland St. J. Braddell, eds. One Hundred Years of Singapore. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 ONE-[HIS])

Ong, Edward K. W., ed. The YMCA of Singapore: 90 Years of Service to the Community. Singapore: YMCA, 1992. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 267.395957 YMC)

Peter, Bruce. Form Follows Fun: Modernism and Modernity in British Pleasure Architecture 1925–1940. London: Routledge, 2007.

Saunders, John and Peter Horton. “Goodbye Renaissance Man: Globalised Concepts of Physical Education and Sport in Singapore.” Sport in Society 15, no. 10 (2012): 1381–95.

Singapore Amateur Swimming Association. Singapore Amateur Swimming Association, 1939–1989. Singapore: SASA, 1989. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 797.200605957 SIN)

Singapore Swimming Club. Official Opening of New Club House. Singapore: Straits Times Press, 1936. (Call no. RRARE 797.200605957 SIN; Microfilm NL9938)

Syonan, Tokubetu-si. The Good Citizen’s Guide. Singapore: Syonan Sinbun, 1943. (From National Library Online; Call no. RRARE 348.5957026 SYO-[LKL]; Microfilm NL7400)

Tan, Choon Kiat. “A History of Tanjong Pagar: 1823–1911.” BA (Hons) thesis, National University of Singapore, 1989, https://scholarbank.nus.edu.sg/handle/10635/166935.

Turnbull, C. M. A History of Modern Singapore 1819–2005. Singapore: NUS Press, 2009. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS])

Yap, R., ed. Singapore Chinese Swimming Club: 88 Years and Beyond. Singapore: Chinese Swimming Club, 1998. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING q797.21095957 SIN)

Yeo, Toon Joo, ed. Singapore Swimming Club: The First 100 Years. Singapore: YTJ and Singapore Swimming Club, 1994. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 797.210605957 TAN)

Yeoh, Brenda S. A. Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore: Power Relations and the Urban Built Environment. Singapore: NUS Press, 2003. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 307.76095957 YEO)

Newspaper Articles (From NewspaperSG)

Daily Advertiser. “No Facilities for Bathing in Singapore.” 15 January 1891, 2.

—. “Correspondence.” 10 August 1892, 3.

Malaya Tribune. “Education in 1921: Annual Report for the Straits Settlements.” 24 August 1922, 9.

—. “Swimming: Raffles Institution Contests.” 12 October 1923, 8.

—. “Another Lung.” 19 June 1929, 10.

—. “Chinese Exhibition.” 20 August 1929, 10.

—. “A Chinese Recreation Ground.” 25 September 1929, 8.

—. “Chinese Topics.” 26 September 1930, 12.

Mid-Day Herald. “A Standing Nuisance.” 31 March 1896, 2.

—. “Tuesday, August 17, 1897.” 17 August 1897, 2.

Singapore Chronicle. “Bathing Place.” 24 May 1827, 2.

—. “Deserters from the Inglis.” 17 January 1828, 2.

—. “The Ministry.” 31 January 1828, 2.

—. “Singapore.” 9 August 1832, 3.

—. “Singapore.” 14 November 1833, 3.

—. “Singapore.” 14 February 1835, 3.

—. “Singapore.” 31 October 1835, 3.

Singapore Daily Times. “The Police Court.” 7 June 1877, 3.

—. “Indecent Bathing.” 12 July 1877, 3.

—. “Building Sites on Mr Scott’s Estate, Tanglin [Advertisement].” 16 January 1878, 2.

—. “An Unknown Club.” 17 May 1878, 3.

—. “Advertisement: The Singapore Waterfall.” 10 June 1878, 2.

—. “The Municipality.” 19 February 1880, 2.

—. “Municipal Engineer’s Office.” 14 September 1880, 2.

—. “Correspondence.” 11 May 1881, 3.

Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser. “Piracy.” 24 March 1836, 3.

—. “Miscellaneous.” 3 August 1843, 2.

—. “To Correspondents.” 19 October 1843, 2.

—. “Untitled.” 26 November 1846, 3.

—. “The Free Press.” 1 February 1849, 3.

—. “Correspondence.” 9 November 1849, 2.

—. “Local.” 26 November 1852, 2.

—. “Local.” 24 December 1852, 3.

—. “The Free Press.” 24 June 1853, 3.

—. “Municipal Commissioners.” 1 April 1858, 3.

—. “Municipal Commissioners.” 20 May 1858, 3.

—. “Swimming as Exercise.” 26 October 1865, 2.

—. “The Singapore Free Press.” 9 November 1865, 2.

—. “The Singapore Free Press.” 11 January 1866, 2.

—. “The Singapore Free Press.” 21 June 1866, 2.

—. “Sports at New Harbour Dock.” 4 September 1889, 300.

—. “Thursday August 11, 1892.” 11 August 1892, 2.

—. “Topics of the Week.” 13 August 1892, 3.

—. “The Swimming Club: A Flourishing Institution, Its Past and Present.” 30 October 1902, 14.

—. “Recreation Facilities.” 22 December 1930, 13.

—. “Page 9 Advertisements Column 5.” 31 January 1931, 9.

Straits Budget. “Swimming.” 15 September 1927, 27.

Straits Eurasian Advocate. “Local and General.” 28 April 1888, 6.

Straits Observer. “Municipal Engineer’s Office.” 8 October 1875, 3.

—. “A Growler.” 11 July 1876, 2.

—. “The Straits Observer.” 4 November 1876, 2.

Straits Times. “Batavia.” 8 April 1846, 2.

—. “The Straits Times.” 30 December 1846, 3.

—. “The Grand Jury’s Presentment.” 25 April 1849, 3.

—. “Page 2 Advertisements Column 4.” 8 January 1850, 2.

—. “A Few Hints on Sea Bathing.” 23 July 1850, 7.

—. “Untitled.” 19 July 1853, 5.

—. “Municipal Commissioners,” 17 October 1855, 5.

—. “Untitled.” 30 November 1861, 2.

—. “Saturday, 21st February.” 21 February 1863, 3

—. “Tuesday 18th April.” 22 April 1865, 2.

—. “Sea Bathing.” 15 November 1865, 2.

—. “Sea Bathing.” 3 January 1874, 2.

—. “Municipal Commissioners.” 21 February 1874, 2.

—. “Cartouche Sketches in Singapore No. 4.” 14 March 1874, 4

—. “Municipal Commissioners.” 21 March 1874, 2.

—. “Legislative Council.” 26 December 1874, 4

—. “Wednesday 26th April.” 29 April 1876, 4.

—. “Carelessness of Native Servants.” 17 June 1876, 1.

—. “Untitled.” 8 May 1883, 2.

—. “Page 4 Advertisements Column 6.” 21 March 1885, 4.

—. “Page 4 Advertisements Column 3.” 21 April 1885, 4.

—. “Untitled.” 1 February 1886, 2.

—. “An European Bath House.” 25 October 1887, 2.

—. “Municipal Commissioners.” 9 May 1889, 3.

—. “Municipal Ordinance Amendment.” 20 August 1889, 3.

—. “Bathing in the Reservoir.” 1 July 1896, 2.

—. “On the Verandah.” 7 May 1898, 2.

—. “Bathing and Swimming.” 11 May 1898, 2.

—. “Drowned at Water Polo.” 2 March 1903, 4.

—. “Untitled.” 23 April 1903, 4

—. “Untitled.” 31 July 1918, 8.

—. “YMCA Swimming Carnival.” 9 October 1920, 10.

—. “Singapore Girl Guides.” 17 February 1921, 8.

—. “Untitled.” 10 March 1924, 8.

—. “The Great Flood: A Day of Venetian Scenes in Singapore.” 9 January 1925, 9.

—. “Far East Olympiad.” 22 May 1925, 15.

—. “Singapore Swimming Club.” 10 August 1925, 10.

—. “Eastern Olympiad.” 24 September 1927, 10.

—. “New Swiss Club.” 19 December 1927, 11.

—. “Page 11 Advertisements Column 2.” 16 July 1928, 11.

—. “New Golf Course.” 23 September 1929, 13.

—. “New Public Park at Pasir Panjang.” 3 January 1930, 13.

—. “Singapore Swimming Club’s Future.” 4 April 1930, 15.

—. “More Amenities for Singapore.” 23 April 1930, 12.

—. “Municipality and Sport.” 28 October 1930, 15.

—. “Open Spaces.” 26 November 1930, 13.

Straits Times Overland Journal. “Tuesday 10th January.” 18 January 1871, 5.

—. “Wednesday 2nd February.” 9 February 1881, 7.

—. “The Municipality.” 15 September 1881, 2.

—. “The Municipality.” 31 December 1881, 3.

Straits Times Weekly Issue. “Another Growl.” 18 October 1884, 16.

—. “Local and General.” 17 June 1886, 2.

—. “Strange Sights.” 31 October 1887, 12.

—. “Municipal President’s Progress Report for May 1889.” 20 June 1889, 5.

—. “What a Newcomer Wants.” 2 August 1889, 3.

—. “Singapore Rowing Club.” 30 September 1889, 7.

—. “New Year Sports.” 24 December 1889, 2.

—. “Thursday, 15th December.” 20 December 1892, 4.

—. “A Singapore Swimming Club.” 14 November 1893, 2.

NOTES

-

“Selangor Notes,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 15 June 1896, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A Big Splash,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 12 January 1931, 20 (From NewspaperSG); Ying-Kit Chan, “‘Sports is Politics’: Swimming (and) Pools in Postcolonial Singapore,” Asian Studies Review 40, no. 1 (2016): 21. From the mid-20th century, the public was increasingly given access to these modern leisure environments that supported a changing economy, military and popular lifestyle in Singapore, which is something I have written about elsewhere. See Jesse O’Neill and Nadia Wagner, “Leisure for the Modern Citizen: Swimming in Singapore,” in Design and Modernity in Asia: National Identity and Transnational Exchange, 1945–1990, ed. Yunah Lee and Megha Rajguru (London: Bloomsbury, 2022), 71–86. ↩

-

“Open Spaces,” Straits Times, 26 November 1930, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chan, “‘Sports is Politics’,” 21. ↩

-

Jocelyn Lau and Lucien Low, eds., Great Lengths: Singapore’s Swimming Pools, 2nd ed. (Singapore: Kucinta, 2017) (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 797.20095957 GRE); R. Yap, ed., Singapore Chinese Swimming Club: 88 Years and Beyond (Singapore: Chinese Swimming Club, 1998) (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING q797.21095957 SIN); Yeo Toon Joo, ed., Singapore Swimming Club: The First 100 Years (Singapore: YTJ and Singapore Swimming Club, 1994) (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 797.210605957 TAN); Chinese Swimming Club (Singapore), The Chinese Swimming Club Souvenir 1951 (Singapore: Chinese Swimming Club, 1951) (From National Library Singapore, call no. RUR 797.2106095957); J. A. Gagan, The Singapore Swimming Club: An Illustrated History and Description of the Club (Singapore: Times Printers, 1968). ↩

-

John Saunders and Peter Horton, “Goodbye Renaissance Man: Globalised Concepts of Physical Education and Sport in Singapore,” Sport in Society 15, no. 10 (2012): 1381–95; Peter Horton, “Singapore: Imperialism and Post-Imperialism, Athleticism, Sport, Nationhood and Nation-building,” International Journal of the History of Sport 30, no. 11 (2013): 1221–34; Nick Aplin, “The Rise of Modern Sport in Colonial Singapore: The Singapore Cricket Club Leads the Way,” in The Routledge Handbook of Sport in Asia, ed. Fan Hong and Lu Zhouxiang (New York: Routledge, 2021), 190–205. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 796.095 ROU) ↩

-

Nick Aplin, Sport in Singapore: The Colonial Legacy (Singapore: Straits Times Press, 2019), 23. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 796.095957 APL) ↩

-

Early news articles using this meaning of the word “swimming” included “Deserters from the Inglis,” Singapore Chronicle, 17 January 1828, 2; “Piracy,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 24 March 1836, 3; “Batavia,” Straits Times, 8 April 1846, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Francoise de Bonneville, The Book of the Bath (New York: Rizzoli, 1998), 6; Sigfried Giedion, Mechanisation Takes Command (New York: Oxford University Press, 1948), 628–76. ↩

-

“Singapore,” Singapore Chronicle, 31 October 1835, 3; “Miscellaneous,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 3 August 1843, 2; “A Few Hints on Sea Bathing,” Straits Times, 23 July 1850, 7; “Sports at New Harbour Dock,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 4 September 1889, 300; “New Year Sports,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 24 December 1889, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ian Bradley, Health, Hedonism and Hypochondria: The Hidden History of Spas (London: Tauris Parks, 2020), 126; Kenneth Lindley, Seaside Architecture (London: Hugh Evelyn, 1973), 7. ↩

-

Balneotherapy is the medical treatment of disorders through both drinking and bathing in thermal mineral waters from natural springs. Hydrotherapy, a later development, refers to the treatment of ailments through water from any source and through a variety of techniques that could involve exercise, bathing, and wrapping in wet cloths. ↩

-

Bradley, Health, Hedonism and Hypochondria, 8–9. ↩

-

“Singapore,” Singapore Chronicle, 9 August 1832, 3; “Singapore,” Singapore Chronicle, 14 November 1833, 3; “Singapore,” Singapore Chronicle, 14 February 1835, 3; “The Straits Times,” Straits Times, 30 December 1846, 3; “Untitled,” Straits Times, 30 November 1861, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Singapore Free Press,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 9 November 1865, 2; “Wednesday 26th April,” Straits Times, 29 April 1876, 4; “Untitled,” Straits Times, 8 May 1883, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Bathing Place,” Singapore Chronicle, 24 May 1827, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Walter Makepeace, Gilbert E. Brooke and Roland St. J. Braddell, eds., One Hundred Years of Singapore (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991), 320. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 ONE-[HIS]) ↩

-

“Bathing Place.” ↩

-

Fred Gray, Designing the Seaside: Architecture, Society and Nature (London: Reaktion, 2006), 147. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART 720.941 GRA) ↩

-

“Bathing Place.” ↩

-

“The pagar consisted of a fence with not more than two or three inches of space between the vertical palings. And with barbed wire nailed to that. […] The pagar also had a diving tower and a chute. Plus changing rooms and a covered area.” Lynne Copping, Life on Pulau Brani, letter from Bob Pattimore, Singapore Memory Project, accessed 15 June 2023. ↩

-

“The Ministry,” Singapore Chronicle, 31 January 1828, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Straits Observer,” Straits Observer, 4 November 1876, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Straits Observer”; Charles Burton Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore 1819– 1967 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984), 732. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 BUC-[HIS]) ↩

-

“Untitled,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 26 November 1846, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Correspondence,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 9 November 1849, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Page 2 Advertisements Column 4,” Straits Times, 8 January 1850, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Building Sites on Mr Scott’s Estate, Tanglin [Advertisement],” Singapore Daily Times, 16 January 1878, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Buckley, Anecdotal History, 732. ↩

-

Buckley, Anecdotal History, 732. ↩

-

“Page 4 Advertisements Column 6,” Straits Times, 21 March 1885, 4; “Advertisement: The Singapore Waterfall,” Singapore Daily Times, 10 June 1878, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The Tivoli bathhouse was described in the 1870s as the “Tivoli Gardens and Refreshment Rooms”: “Cartouche Sketches in Singapore No. 4,” Straits Times, 14 March 1874, 4; “Page 4 Advertisements Column 3,” Straits Times, 21 April 1885, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

C. M. Turnbull, A History of Modern Singapore 1819–2005 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2009), 82. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS]) ↩

-

John G. Butcher, The British in Malaya 1880–1941: The Social History of a European Community in Colonial South-East Asia (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1979), 157. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 301.4512105951033 BUT) ↩

-

“An Unknown Club,” Singapore Daily Times, 17 May 1878, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Page 9 Advertisements Column 5,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 31 January 1931, 9; Syonan Tokubetu-si, The Good Citizen’s Guide (Singapore: Syonan Sinbun, 1943), 181. (From National Library Online; Call no. RRARE 348.5957026 SYO-[LKL]; Microfilm NL7400) ↩

-

“Swimming as Exercise,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 26 October 1865, 2; “Sea Bathing,” Straits Times, 15 November 1865, 2; “The Singapore Free Press,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 21 June 1866, 2; “Sea Bathing,” Straits Times, 3 January 1874, 2; “An European Bath House,” Straits Times, 25 October 1887, 2; “What a Newcomer Wants,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 2 August 1889, 3; “No Facilities for Bathing in Singapore,” Daily Advertiser, 15 January 1891, 2; “Thursday August 11, 1892,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 11 August 1892, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A Growler,” Straits Observer, 11 July 1876, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Sea Bathing.” ↩

-

“Another Growl,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 18 October 1884, 16; “Topics of the Week,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 13 August 1892, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore Rowing Club,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 30 September 1889, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A Singapore Swimming Club,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 14 November 1893, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Municipal Commission,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 25 May 1900, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“To Correspondents,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 19 October 1843, 2; “The Grand Jury’s Presentment,” Straits Times, 25 April 1849, 3; “Correspondence,” Daily Advertiser, 10 August 1892, 3; “A Standing Nuisance,” Mid-Day Herald, 31 March 1896, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Indecent Bathing,” Singapore Daily Times, 12 July 1877, 3; “Untitled,” Straits Times, 1 February 1886, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Singapore Free Press,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 11 January 1866, 2; “Tuesday 10th January,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 18 January 1871, 5; “Carelessness of Native Servants,” Straits Times, 17 June 1876, 1; “Correspondence,” Singapore Daily Times, 11 May 1881, 3; “Strange Sights,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 31 October 1887, 12; “Local and General,” Straits Eurasian Advocate, 28 April 1888, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Local and General,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 17 June 1886, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Free Press,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 1 February 1849, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 19 July 1853, 5; “Municipal Commissioners,” Straits Times, 17 October 1855, 5; “The Police Court,” Singapore Daily Times, 7 June 1877, 3; “Municipal Ordinance Amendment,” Straits Times, 20 August 1889, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Brenda S. A. Yeoh, Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore: Power Relations and the Urban Built Environment (Singapore: NUS Press, 2003), 183. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 307.76095957 YEO) ↩

-

“Local,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 26 November 1852, 2; “Local,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 24 December 1852, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Bathing in the Reservoir,” Straits Times, 1 July 1896, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Municipal Commissioners,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 1 April 1858, 3; “Municipal Commissioners,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 20 May 1858, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Municipal Engineer’s Office,” Straits Observer, 8 October 1875, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Municipal Commissioners,” Straits Times, 21 February 1874, 2; “Municipal Commissioners,” Straits Times, 21 March 1874, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 19 February 1880, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Municipal Engineer’s Office,” Singapore Daily Times, 14 September 1880, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Wednesday 2nd February,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 9 February 1881, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan Choon Kiat, “A History of Tanjong Pagar: 1823–1911” (BA (Hons) thesis, National University of Singapore, 1989), 2. ↩

-

“The Municipality,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 31 December 1881, 3; “The Municipality,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 15 September 1881, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Municipal Commissioners,” Straits Times, 9 May 1889, 3; “Municipal President’s Progress Report for May 1889,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 20 June 1889, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Yeoh, Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore, 178; “Municipal Commission,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 6 May 1897, 2; “Tuesday, August 17, 1897,” Mid-Day Herald and Daily, 17 August 1897, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Buckley, Anecdotal History, 453; “Tuesday 18th April,” Straits Times, 22 April 1865, 2; “The Free Press,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 24 June 1853, 3; “Saturday, 21st February,” Straits Times, 21 February 1863, 3 (From NewspaperSG); “Indecent Bathing.” ↩

-

“The Free Press.” ↩

-

“Thursday, 15th December,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 20 December 1892, 4; “The Great Flood: A Day of Venetian Scenes in Singapore,” Straits Times, 9 January 1925, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Swimming Club: A Flourishing Institution, Its Past and Present,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 30 October 1902, 14; Cheong K. L. and Chia K. Y., “Early Years,” in The Chinese Swimming Club Souvenir 1951 (Singapore: Chinese Swimming Club, 1951), 15. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RUR 797.2106095957) ↩

-

“On the Verandah,” Straits Times, 7 May 1898, 2; “Bathing and Swimming,” Straits Times, 11 May 1898, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Free Press”; “Wednesday 26th April”; “Untitled.” ↩

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 23 April 1903, 4 (From NewspaperSG); Singapore Swimming Club, Official Opening of New Club House (Singapore: Straits Times Press, 1936), 2, 23. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 797.200605957 SIN; Microfilm NL9938) ↩

-

Cheong and Chia, “Early Years,” 15; “Untitled,” Straits Times, 31 July 1918, 8; Untitled, Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 3 October 1918, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Swimming Club.” ↩

-

C. Jackson, Our Singapore: Sketches of Local Life (Singapore: n.p., 1914), 23. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 959.57 JAC) ↩

-

“On the Verandah.” ↩

-

“The Swimming Club: The President’s Prize,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 8 October 1902, 234; “Drowned at Water Polo,” Straits Times, 2 March 1903, 4; “Swimming: Raffles Institution Contests,” Malaya Tribune, 12 October 1923, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“YMCA Pool,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 7 July 1920, 12; “Singapore’s Water Supply: Fort Canning Negotiations,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 30 November 1922, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Edward K. W. Ong, ed., The YMCA of Singapore: 90 Years of Service to the Community (Singapore: YMCA, 1992), 4 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 267.395957 YMC); “Lecture at the YMCA: Physical Culture in Singapore,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 10 January 1918, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Education in 1921: Annual Report for the Straits Settlements,” Malaya Tribune, 24 August 1922, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Cheong and Chia, “Early Years,” 17; “Far East Olympiad,” Straits Times, 22 May 1925, 15; “Swimming: The YMCA Carnival,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 2 November 1925, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“YMCA Swimming Carnival,” Straits Times, 9 October 1920, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“YMCA Swimming Pool,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 21 December 1920, 12; “Swimming Pool,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 13 August 1921, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“YMCA Pool”; “Singapore Girl Guides,” Straits Times, 17 February1921, 8; “Untitled,” Straits Times, 10 March 1924, 8; “Chinese Topics,” Malaya Tribune, 26 September 1930, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Bruce Peter, Form Follows Fun: Modernism and Modernity in British Pleasure Architecture 1925–1940 (London and New York: Routledge, 2007), 45–46. ↩

-

“New Public Park,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 17 September 1929, 9; “Swimming in Clean Water!” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 2 May 1930, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Bathing Fatality: Evidence at Coroner’s Inquest,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 22 July 1925, 52. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore Swimming Club,” Straits Times, 10 August 1925, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee C. Q. “25 Years of Progress and Expansion,” in The Chinese Swimming Club Souvenir 1951 (Singapore: Chinese Swimming Club, 1951), 29 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RUR 797.2106095957); “Advertisements,” Straits Times, 16 July 1928, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“New Swiss Club,” Straits Times, 19 December 1927, 11; “Tanglin Club Swimming Pool,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 1 May 1930, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“New Golf Course,” Straits Times, 23 September 1929, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A Chinese Recreation Ground,” Malaya Tribune, 25 September 1929, 8; “New Public Park at Pasir Panjang,” Straits Times, 3 January 1930, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Legislative Council,” Straits Times, 26 December 1874, 4 (From NewspaperSG); A. Ferguson, “Extracts from the Sanitary Report of the 2nd and 4th Batteries 17th Brigade Royal Artillery, Stationed at Singapore, from the 15th September to the End of the Year 1863,” Army Medical Department. Statistical, Sanitary and Medical Reports for the Year 1863, vol. 5 (London: n.p., 1863), 385. ↩

-

“Swimming Club Meeting,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 2 April 1928, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Swimming Club: The Alternative Site Problem,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 8 April 1929, 16; “Singapore Swimming Club’s Future,” Straits Times, 4 April 1930, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Swimming Club Not to Move,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 15 September 1930, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Singapore Swimming Club, Official Opening of New Club House. ↩

-

R. H. Bruce Lockhart, Return to Malaya (London: Putnam, 1936), 113. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.5 LOC-[ET]) ↩

-

Lee, “25 Years of Progress and Expansion,” 29. ↩

-

“Another Lung,” Malaya Tribune, 19 June 1929, 10; “Municipality and Sport,” Straits Times, 28 October 1930, 15; “Recreation Facilities,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 22 December 1930, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“New Public Park”; “More Amenities for Singapore,” Straits Times, 23 April 1930, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

In 1927, Mong Guan and Poh Cheng competed in Shanghai (representing China), with Mong Guan placing third overall. “Swimming,” Straits Budget, 15 September 1927, 27; “Eastern Olympiad,” Straits Times, 24 September 1927, 10. Overseas competitions also included exhibition competitions such as the Hong Kong Chinese Athletic Meeting in 1929, which was attended by Singaporean teams. “Chinese Exhibition,” Malaya Tribune, 20 August 1929, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The initial meeting was between the YMCA, Chinese Swimming Club and Singapore Swimming Club. After its formation, the Singapore Amateur Swimming Association was joined by Tiger Swimming Club, Cantonese Swimming Union, Oversea Chinese Swimming Club and the British Armed Forces as affiliates. Singapore Amateur Swimming Association, Singapore Amateur Swimming Association, 1939–1989 (Singapore: SASA, 1989), 10–12. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 797.200605957 SIN) ↩

-

Nick Aplin, “Sport in Singapore (1945–1948): From Rehabilitation to Olympic Status,” International Journal of the History of Sport 33, no. 12 (2016): 1361–79. ↩

-

Lee, “25 Years of Progress and Expansion,” 31. ↩