The Forgotten Murals of Paya Lebar Airport

Three large murals used to grace the walls of Paya Lebar Airport, depicting scenes from Singapore and Malaysia. Dahlia Shamsuddin has the inside story of how they came to be.

Before Changi Airport, there was Paya Lebar Airport. Opened in 1955, Paya Lebar Airport was Singapore’s gateway to the world and one of the most modern airports of its time. However, as Singapore grew in importance as an air hub and a destination in its own right, further expansion was necessary to cope with the increasing number of passengers using the airport. In November 1962, work began on a new International Passenger Terminal Building. It was completed in April 1964 at a cost of $3.5 million.

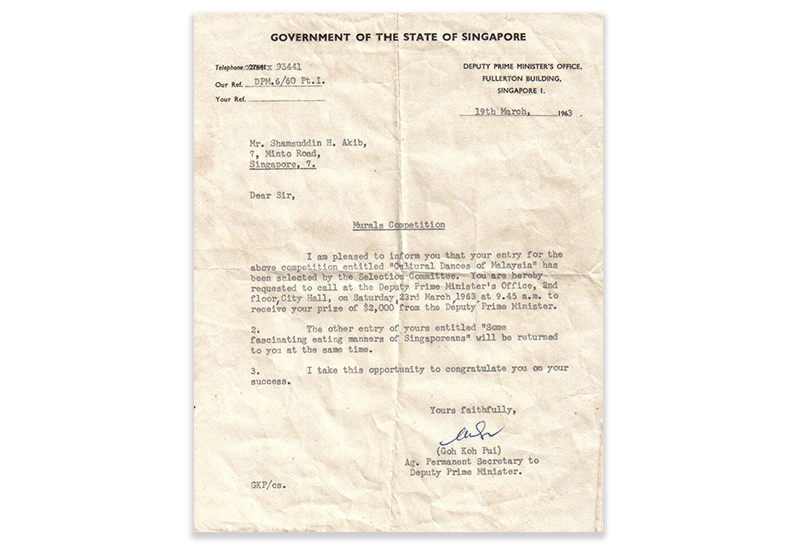

In a presumed effort to add a dash of colour to this new building, the government decided that large murals would adorn its walls. On 1 October 1962, a small notice published in The Straits Times invited artists to “submit designs for suitable murals which will be executed at five places in the Passenger Terminal Building of the Singapore Airport”.1 Each of the five winning designs would receive a cash prize of $2,000.

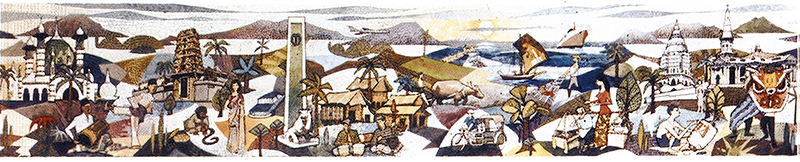

In the end, however, only three designs were chosen. Two were done by a Singapore-based British art director, William P. Mundy, which showed what The Straits Times described as “a panoramic view of Singapore by night” and “a Malaysian panorama”.2 The third winning design, which depicted “the cultural dances of Malaysia”, was created by one Shamsuddin H. Akib – my father.3

The Murals Competition

My father, a commercial artist, and Mundy (Bill as he prefers to be called) were colleagues at Papineau Advertising during the 1960s where Bill was the art director. My father and Bill were 30 and 26 years old respectively when they won the mural design competition.

My father is a self-taught artist. Born in Singapore in 1933, he started out as a peon (office boy) in the Commissioner-General Office but realised advancement prospects were limited and that he was capable of more. He briefly joined The Straits Times as an apprentice artist before moving to Papineau Advertising as they were looking for someone who could write Jawi in a calligraphic style. My father had taken part in other competitions before, winning a poster competition on diphtheria in 1959 and later coming in second place in a poster competition for the National Language campaign organised by The Straits Times in 1964.4

Bill first came to Singapore in 1957 as a soldier during his national service. He was based at Gillman Barracks doing cartographic work. He left Singapore a year later after completing his national service before returning in 1960 to work in Papineau Advertising. He was hired as a visualiser and was promoted to art director after six months.

My father was already working in Papineau when Bill joined, and regards Bill as his mentor and friend. Bill was very particular and pushed my father and his colleagues hard at work, but they learned a lot from him as my father recalls.

When Bill and my father heard about the competition, they decided separately that they would take part but did not discuss their designs with each other. When my father found out that Bill was planning to submit two designs, he decided he would do the same. “If Bill can submit two designs, so can I,” he told me.

Both men submitted two designs each, one portraying Singapore and the other Malaysia. My father’s second design was titled “Some Fascinating Eating Manners of Singaporeans”. This design was eventually not selected and was returned to my father. Unfortunately, my father cannot remember the details of this design, which is a shame given its intriguing title.

Submitting separate designs to represent Singapore and Malaysia was a strategic decision on the part of both men. They were not sure if the organisers would prefer a design focusing on Singapore or Malaysia, especially as this contest was being held in the months leading up to the formation of the Federation of Malaysia in September 1963.

They believed, probably rightly, that the chances of winning at least one prize would be higher by submitting two separate designs each. They guessed that the judging panel, led by Cathay Organisation head Loke Wan Tho, would comprise people from Singapore and Malaysia, and figured that these judges would likely have their preferences when it came to what would be considered as suitable designs for the new passenger terminal building. It turned out that Bill and my father guessed right.

The prize collection ceremony was held at City Hall on 23 March 1963, a Saturday morning. Deputy Prime Minister Toh Chin Chye presented Bill with a cheque for $4,000 for his two winning creations while my father received $2,000 for his design. Bill and my father never found out why only three designs were picked rather than the planned five. Bill’s murals were titled “Skyline of Singapore” and “Races and Religions of Malaysia”, while my father’s was called “Cultural Dances of Malaysia”.

The money was a princely sum at the time. In comparison, the monthly rent for a three-room flat in the newly completed Selegie House was $90.5 With his prize money, Bill bought a green Triumph TR4 sports car which was waiting for him at the airport in London when he went back for a visit. He later had the car shipped to Singapore and he drove it around for the next 18 months before leaving for a new job in Hong Kong. My parents had more practical concerns; they were expecting their first child (me) a few months after my father won the competition and the extra money would have come in handy.

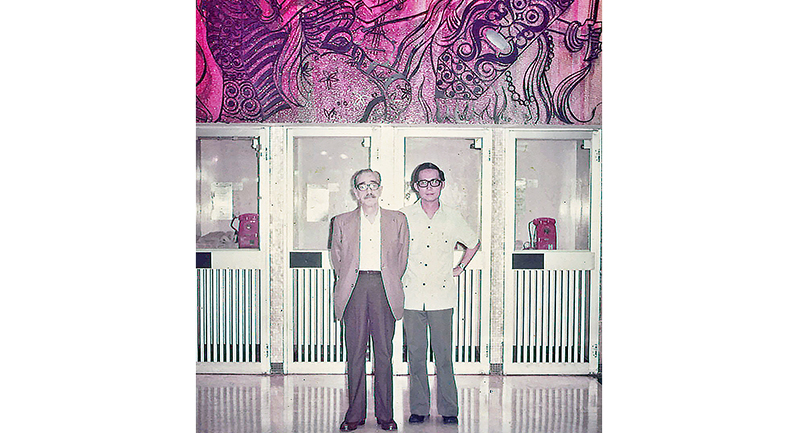

My father’s mural of the cultural dances of Malaysia, which measured about 9 metres by 1.5 metres, was installed on the ground floor of Paya Lebar Airport. As you entered the building and turned left, you would see my father’s mural on the wall at the far end, above a bank of phone booths. That location turned out to be a popular spot for people to take photos before flying off.

Bill’s mural of Singapore’s cityscape at night was the longest of the three, at about 12 metres by 1.5 metres. It was installed on the opposite end of the building from my father’s mural, at the staircase landing one floor up. Due to the open-concept design of the concourse, this mural was still visible from the ground floor though. Bill’s second mural of Malaysian scenes, however, was much less visible as it was installed in the transit lounge on the ground floor. (The dimensions of this mural are not available.)

Of Mosaic and Iron

Although Bill and my father did not discuss their designs beforehand, the two men agreed on the basic material for the murals – Italian mosaic or coloured Smalti glass. Bill had seen these being used in Singapore and thought that it would be suitable for the murals.

Bill had originally planned to return home to Britain for a visit shortly after the winners of the mural design competition were announced. As his flight from Singapore to London would include a stopover in Rome, at the prize giving ceremony Bill told Dr Toh that he was prepared to stop in Murano, Venice, for a few days to visit the mosaic factory and supervise the colour selection of the Smalti glass if the Singapore government would pay for the cost of his stay. Dr Toh agreed, and the government made arrangements for Bill’s stay in Venice and also provided him with an allowance.6

The three murals were rendered in different colour schemes and designs. My father’s mural used red and orange Smalti glass pieces as the backdrop. To make the dancers more prominent, he designed them out of thin iron strips, in a dark colour. The figures were then affixed to the tiles so that they protruded slightly.

It was not an easy task assembling my father’s mural. He recalls going to a shipyard in Tanjong Rhu to supervise the Chinese workers who were bending the iron to create the figures of the dancers, and one of them telling him “Wah! Lu punya banyak susah!” [“Wah! Your (design) is so difficult!”].

My father’s mural depicts four types of Malaysian dance forms – represented by a pair of Indian dancers, a pair of Chinese wayang (opera) dancers, a traditional dancer from Sarawak and a pair of mak yong dancers from the state of Kelantan. (mak yong is a traditional form of dance-drama prevalent in the area.)

My family has a personal connection to Kelantan as my father’s eldest sister had moved to the state with her husband in the mid-1940s, after the war. Over the years, my father would regularly visit my aunt up north. So the mak yong dancers were probably inspired by this link with Kelantan.

Bill’s mural of Singapore at night depicts the financial district in 1962 from the vantage point of the Singapore River. Blue, purple and green were the predominant colours. The mural shows landmarks such as the General Post Office Building (present-day Fullerton Hotel) and the Asia Insurance Building (now known as the Ascott Raffles Place) among other structures. Bill chose this scene because it was iconic, he told me.

For his second mural, Bill used well-known religious and non-religious landmarks, modes of transportation, a snake charmer, a satay seller, a lantern maker and Singapore’s Merdeka Lion to depict different aspects of Singapore and Malaysia. He only used mosaic tiles in both of his murals.

In Bill’s case, the mosaic tiles arrived in Singapore in sheets from Italy with the design and colours already laid out according to his design. Affixing the mosaic tiles onto the wall was not a difficult task. My father’s design with the iron figures, however, was more challenging to install; also, it was the only mural that was partly constructed in Singapore.

The Murals Today

Even though my family would go to Paya Lebar Airport in the 1970s, we never thought to pose for a photograph in front of my father’s mural. Bill does not have a photograph of himself with his murals either. When the government announced plans in June 1975 to build a new airport in Changi to replace Paya Lebar,7 it never occurred to us to take a picture of my father’s mural. We probably assumed that the Paya Lebar Airport building and the mural would be around forever and that we could always visit it. However, once Changi Airport became operational in 1981, Paya Lebar Airport was transferred to the Republic of Singapore Air Force and became a military airbase.8 Gaining access to the building would no longer be easy.

In 2010, the Ministry of Defence (MINDEF) gave my father and me permission to visit Paya Lebar Airbase to view the murals. My reaction was “Finally! At last!” When we got there, we could easily spot Bill’s mural of the Singapore skyline. However, we could not see the other two murals on the ground floor at all because the space had been partitioned into office cubicles, with walls hidden behind plasterboards.

Armed with a map based from the 1964 souvenir programme for the opening of the new terminal, we walked around the ground floor, peering behind plasterboard walls. A small army of people from MINDEF and the Republic of Singapore Air Force even joined us in the search. Despite our best efforts, we were disappointed that we could not find the two murals.

In early 2012, Bill was on a visit to Singapore and I invited him to attend the opening of an exhibition at the National Library Building commemorating the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Singapore. At the event, we were told by someone who had seen all three murals that only Bill’s skyline of Singapore at the staircase landing was still intact.

Bill was silent when he heard the news. I asked about the state of the other two murals and was informed that the bottom half of Bill’s mural on Malaysian scenes had been removed. The iron dancers in my father’s mural had likewise been prised off and only the orange-red mosaic background remained. I went home and informed my father of the fate that had befallen his mural. Like Bill, my father said nothing when I broke the news to him.

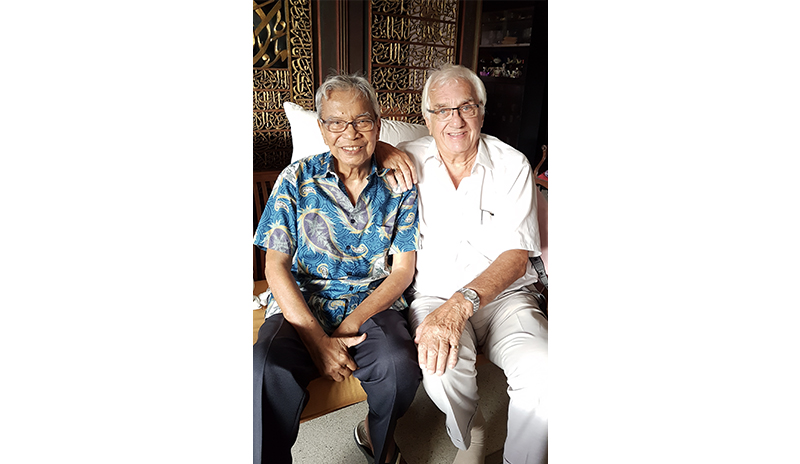

In 2015, when Bill visited my father at home, I asked them how they felt upon hearing about the fate of the murals in 2012. They expressed their shock and sadness at what had happened. Bill also revealed that he liked my father’s mural best because it was timeless. In a 2016 email to me, he said: “I thought your father’s design the best of the three. It was so striking in oranges and red with very modern use of the dark metal.”

It has been close to 60 years since Bill and my father won the mural competition. In the meantime, both men have gone on to distinguished careers. My father eventually left Papineau and joined publisher Donald Moore before working for various international advertising agencies in Singapore. In the 1980s, he became a freelance graphic artist and continued doing commissions until his late 60s. In 2015, he was awarded the Singapore Design Golden Jubilee Award for Visual Communication.

Bill left Singapore in 1964 and worked in Hong Kong and Bangkok before returning here in 1970 as the regional director of advertising agency Grant K&E. He went back to the United Kingdom in 1978 to become a full-time artist. Bill has been described as one of the world’s leading miniature portrait painters and has painted the portraits of members of the British and Malaysian royal families.

Despite their many accomplishments, Bill and my father still regard the Paya Lebar Airport murals with much affection as winning the murals competition was one of the early highlights of their careers. My father told me that he had taken part in the competition because if he had won, his design would have been seen by many local and overseas visitors. It was a prestigious competition and being one of the winners brought him a lot of attention.

Bill said he was hopeful that at least one of his designs would clinch a prize and was delighted when both were selected. In an email to me in May 2021, Bill wrote: “When I entered the competition in 1962/1963, my first idea was to capture the panoramic scene of the Singapore skyline at evening time; mainly by using various shades of blue, purple and green. What a contrast to today’s amazing skyline with its magnificent modern skyscrapers. I hope my mural will be remembered as depicting a visual moment in time.”9

My father, on his part, has one wish: that his mural be reconstructed one day.

Given that two of the murals have been lost, it is my hope that the remaining one – Bill’s skyline of Singapore – will be preserved. These murals captured my father’s and Bill’s experience of living and working in Singapore in the early 1960s. The murals also reflected their aspirations for a new, multiracial and independent country. Even after Singapore gained independence in 1965, the underlying message encapsulated in the murals – multiculturalism, development and progress – remains significant today.

Dahlia Shamsuddin is a Senior Librarian with the Resource Discovery & Management, National Library Board, where she catalogues legal deposit, gift and donor materials. She has worked in public, academic, law and national libraries doing reference, circulation, digital and print cataloguing work.

Dahlia Shamsuddin is a Senior Librarian with the Resource Discovery & Management, National Library Board, where she catalogues legal deposit, gift and donor materials. She has worked in public, academic, law and national libraries doing reference, circulation, digital and print cataloguing work.

RELATED ARTICLES

- A Banquet of Malayan Fruits: Botanical Art in the Melaka Straits

- Chinese Graphic Artists in Pre-war Singapore

NOTES

-

Page 17 Advertisements Column 5: Open competition for design of murals in the passenger terminal building, Paya Lebar Airport. (1962, October 1). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Design for airport murals: 2 win prizes. (1963, March 24). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

This essay on the Paya Lebar Airport murals is based on a series of conversations with my father and William Mundy (Bill). The chats were conducted between 2009 and 2016 in Singapore. I also interviewed Bill via email in 2016. My father and Bill have maintained their friendship all these years. Bill is 84 years old and lives in Britain where he is a successful artist. My 88-year-old father worked for local and international advertising agencies in Singapore and he designed the original logos for Mendaki and the old Changi Hospital, the updated logo for the Singapore Heritage Society, and the original book covers for Alex Josey’s Lee Kuan Yew (first published in 1971), Donald and Joanna Moore’s The First 150 Years of Singapore (first published in 1969), and Mahathir Mohamad’s The Malay Dilemma (first published in 1970). ↩

-

Zhuang, J. (2012). Independence: The history of graphic design in Singapore since the 1960s (p. 76). Singapore: The Design Society. (Call no.: RSING 741.6095957 ZHU); Bahasa jiwa bangsa. (1964, August 31). The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Selegie House – how flats are rented out. (1963, May 31). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Email correspondence with Bill Mundy, 2016 and 2021. ↩

-

Changi to be future civil airport. (1975, June 3). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

From airbase to airport. (1981, December 29). The Straits Times, p. 43. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Email correspondence with Bill Mundy, 1 May 2021. ↩