My Grandfather Was a Rōmusha

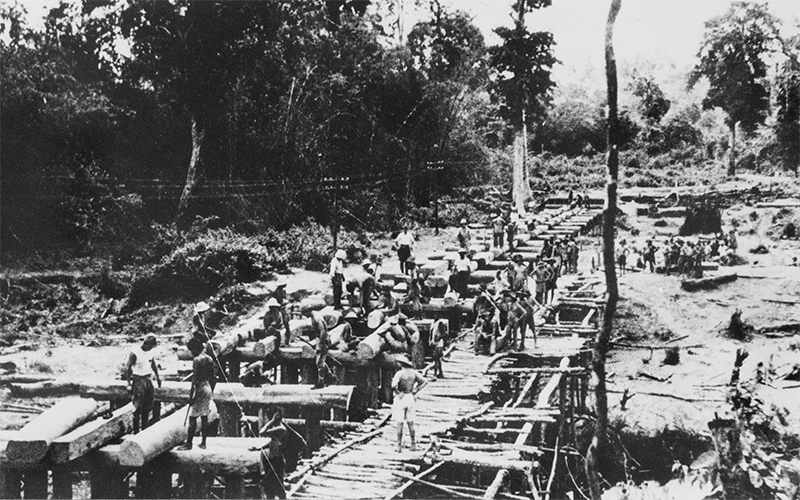

During World War II, forced civilian labourers known as rōmusha were used by the Imperial Japanese Army for hard labour. They helped to build the Death Railway.

By Shirlene Noordin

Growing up, I used to listen to the adults speak about my grandfather who had gone away during the war. I also heard stories from my grandmother about waiting, day after day, for her husband to return home.

For a while, I thought my grandfather had been a soldier who had gone off to fight in the war. Later, I realised that the war he had fought in was not on the battlefields. He was not part of any army and he didn’t carry a weapon. The war he – and so many others like him – fought was set on a treacherous strip of land stretching from Thailand to Burma. Armed with nothing more than shovels and pickaxes, they confronted their enemy: the Imperial Japanese Army and the inhumane conditions the workers were forced to live in.

These people were rōmusha – forced civilian labourers recruited by the Japanese military to perform hard manual labour – who built the Thai-Burma Railway. My maternal grandfather, Kosman Hassan, was among the thousands from Singapore, Malaya, Burma and Java who toiled on the railway that is known today as the Death Railway.

The Death Railway has been immortalised in the movie, The Bridge on the River Kwai, but this Hollywood version of the story focuses on a group of British prisoners-of-war (POWs) and the rōmusha received scant attention. Even beyond the film, the history of the rōmusha is little known and they remain largely invisible in the accounts of the Death Railway.

In fact, there were many more rōmusha working on the railway than there were POWs. It is estimated that there were 200,000 Southeast Asian civilian labourers in contrast to 60,000 Allied POWs on the railway. By the end of the war, more than 90,000 of the rōmusha had perished compared to 16,000 deaths among the POWs.1

Alongside British, Australian, Dutch and some American POWs, these Asian rōmusha did the impossible – they constructed a 415-kilometre railway line which passed through the most difficult of terrains to connect Ban Pong in Thailand to Thanbyuzayat in Burma in a mere 12 months, all in the name of the Japanese war effort. The railway was constructed to “avoid having to transport supplies by dangerous sea routes from its South East Asian territories to the front in Burma, and ultimately to link Bangkok in Siam and Rangoon in Burma”.2

Remembering the Forgotten

Yet, at the end of the Second World War in Southeast Asia, there appears to be no official records of these civilian labourers. No lists of their names or where they were from were compiled and no death records were ever kept that I could find. In the official retelling of the tragedy of the Death Railway, the rōmusha are faceless and voiceless.

In recounting my grandfather’s story of his time on the Thai-Burma Railway, I hope to give a voice, a face and a name to the hundreds of thousands of rōmusha like him who worked on the railway, for which many paid with their lives.

Several accounts about the Thai-Burma Railway were recorded by the POWs of the Allied Forces in their personal diaries and later published in books by those who survived. Whatever little we now know of the rōmusha has been gleaned from these POW accounts. In the diary of British POW Robert Hardie, a former plantation manager in Malaya, he mentions the rōmusha camps, where there were “frightful casualties from cholera and other diseases” and the brutality of the Japanese. He wrote: “People who have been near these camps speak with bated breath of the state of affairs – corpses rotting unburied in the jungle, almost complete lack of sanitation, frightful stench, overcrowding, swarms of flies. There is no medical attention in these camps, and the wretched natives are of course unable to organise any communal sanitation.”3

The rōmusha themselves do not appear to have left any written accounts. Many of them were recruited from remote villages and plantations and were most likely illiterate. Given the high mortality rate, their personal stories of hardship would have perished along with them.

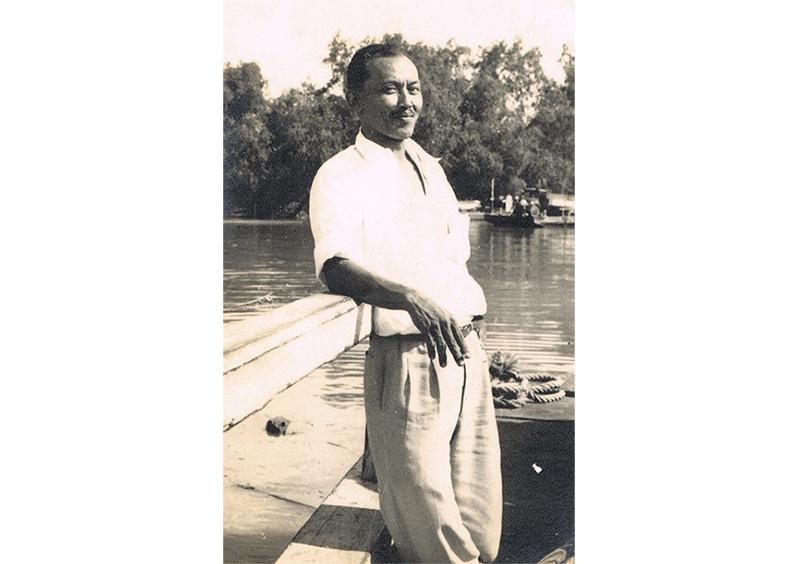

My grandfather, whom I called Bapak, was among those fortunate enough to have survived. What I know of his experience on the railway is from the rare stories he told us, but even then, these were told in a stoic, quiet fashion, without regret, sadness or heroism. It was as if the Death Railway was just an episode he had to go through.

Bapak never really explained to us, his grandchildren, what had exactly happened to him on the Thai-Burma Railway. He would mention in fleeting conversations that he had worked for the Japanese soldiers in the jungles of Thailand during the war. He spoke about the dense jungles full of mosquitos that brought disease and how hard it was to find food. One of his stories that remains with me to this day is about the kindness of the local Thai population whom he came into contact with, and how they gave him food and taught him local cures for his ailments.

It was probably through his interactions with the locals that my grandfather learnt Thai, a language he continued to speak long after the war. The local help he received, I believe, was crucial to his survival.

I didn’t think to ask more questions when my grandfather was alive. I was too young then to understand the significance of his experience but looking back I wish I had.

Early Life

Bapak was born on 8 November 1914 in Singapore. His father Hassan and his father’s brother Majid sailed to Malaya from a village near the town of Pekalongan in Central Java, long known for its batik production and trade.

My great-grandfather, Hassan, eventually travelled south to Singapore, while Majid settled in Kuala Lumpur. In Singapore, Hassan ended up in the Kampong Jawa area and married a Javanese lady living there. My great-grandfather passed away when Bapak was only a young boy and his mother remarried. Bapak grew up in the Kampong Jawa area. He must have gone to a Malay school in Singapore as he was able to read and write in Malay, and could even speak and read English. As a young adult, he worked as a car mechanic.

Bapak married my grandmother, Rokiah Rais, whom I called Mak, just before the war. She was the sister of his friend who was also a mechanic. Bapak was her second husband. From her first husband, she had five children, so upon marrying her, Bapak had an instant family.

Bapak was also a volunteer with the British military. From his collection of medals that I inherited, I was able to trace (with the help of Jonathan Moffat, an archivist for the Malayan Volunteers Group) his service in the Straits Settlements Volunteer Force before the Japanese Occupation.

Bapak’s name appears on the roll of Singapore Fortress Company, Malay section, between 1938 and 1940. According to family stories, my grandfather also served in the Royal Artillery unit. Before the Fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942, he had been stationed on Pulau Blakang Mati (Sentosa today). (This family account may not be entirely accurate because from my research I found out that pre-1945, the Royal Artillery was an exclusively European unit, making it very unlikely that my grandfather was a part of it before 1945.)

Bapak was 28 at the time when he was sent to Thailand, though he need not have gone at all. We were a family of car mechanics, living on Sennett Road on the east coast of Singapore at the time. My great-granduncle Tok Dick (whose real name was Sadali but was nicknamed Dick by his British customers) and granduncles ran a car workshop business on St Thomas Walk in the River Valley area that serviced the many British families in the vicinity before the Japanese Occupation.

When the Japanese military started recruiting local men for the construction of the Thai-Burma railway, Tok Dick and one of his mechanics were called up as the Japanese needed experienced mechanics to work on the railway. Bapak volunteered to take Tok Dick’s place. Being younger and fitter, my grandfather probably thought that he was better suited to the job than my great-granduncle who was about 20 years older than my grandfather.

At the time, nobody knew about the conditions that awaited these men; the Japanese said the workers would receive fair wages, and even promised lodging and food. This could not be further from the truth.

Off to Thailand

I don’t know when exactly my grandfather first set off for Thailand but we know that construction of the railway got underway in July 1942. When he left Singapore, Mak was pregnant with my mother, their first child. She was born on 17 April 1943 without her father present.

From Singapore, Bapak was put on a northbound train to Thailand. My grandfather later told his sons that the train made a stop in Kuala Lumpur where he met up with his Uncle Majid who lived there. Majid passed him a parcel of food for his onward journey. That was probably the last contact my grandfather had with family until after the war.

According to one of my uncles, Ghazaly (Ally) Kosman, my grandfather was put to work on engines and locomotives while he was in Thailand. It is possible that my grandfather ended up in Ban Pong, a town and district in Thailand’s western province of Ratchaburi.

In his autobiography The Railway Man, British POW Eric Lomax wrote that there was a camp outside Ban Pong which had a workshop “staffed by Japanese mechanics and engineers”.4 (Lomax’s story of imprisonment, torture and subsequently forgiveness of his torturers was made into a 2013 movie also called The Railway Man starring Nicole Kidman and Colin Firth.)

Bapak never mentioned the location of his camp, but I recall that he talked about the town of Kanchanaburi, 48 km north-west of Ban Pong town. Perhaps he was in one of the camps around Kanchanaburi (also called Kanburi by the POWs).

My grandfather was good with languages. In addition to Malay and Javanese, he also spoke Hokkien and English. Being conversant in English made it possible for him to communicate with the Japanese soldiers and POWs. He also picked up Japanese and Thai while working on the Thai-Burma Railway. His linguistic skills and his experience as a mechanic undoubtedly shielded him from the worst of what the Death Railway had inflicted on the POWs and Asian labourers.

As a mechanic, Bapak probably did not have to perform the backbreaking manual labour of the other workers who were pickaxing through limestone hills, hauling away heavy debris in baskets, cutting through thick jungle and laying tracks across dangerous ravines and rivers. The further up the line they went, the worse the situation became as the country got wilder, denser and more hilly and where food was even scarcer.

While I speculate that Bapak may have escaped the harshest of work conditions, I can never be sure. What I am certain of, hearing him tell his stories, was that conditions at his camp were extremely rudimentary. He had to fashion a bed out of bamboo, a mere few centimetres off the bare ground. He told us of his encounters with snakes slithering across his body as he slept.

The meagre diet meant that my grandfather was always hungry. Fortunately, he was allowed to leave the camp occasionally to go to the nearby village where he could get food. Being unpaid, I don’t know how he procured the food but being a sociable and friendly person, my grandfather would have definitely made friends with the local Thais.

Bapak also spoke about the many diseases such as malaria, cholera and dysentery that ravaged the labourers and POWs. Death among his fellow labourers was rampant. As he was also responsible for burying the dead, he recalled that he was not even able to give proper burials as these were hastily done. He said that he would have liked to give the Muslims among the deceased rōmusha the proper burial rites, but he was unable to.

The Thai-Burma Railway was finally completed in October 1943 but despite this, the ordeal of the surviving POWs and the Asian labourers was far from over. They were confined in the camps for another two years until the Japanese surrender in 1945. The constant bombings of the railway by the Allied forces required frequent repairs by the POWs and labourers. Bapak was among the labourers who were tasked with felling trees in the jungle for timber to repair tracks and bridges, all while food rations got smaller.

Return to Singapore

When the Japanese surrendered in August 1945, the POWs and rōmusha suddenly found themselves free. While the POWs were able to quickly organise themselves, the rōmusha, who did not have the same military structures in their camps and did not have any leadership, struggled initially.

According to a report from 1946 (courtesy of Jonathan Moffat’s research), “approximately 26,000 Malayans remained as labourers, scattered along the length of the railway… Those who survived would have been abandoned by the Japanese and were actually told in many cases, that they could find their own way back to Malaya. They were in a terrible state of malnutrition and disease, and very few were capable of making even the journey to Bangkok”.5 A group of Malayan British POWs, who were former planters and part of the volunteer forces, helped to repatriate the Malayan labourers from Kanchanaburi and Bangkok.

In an obituary for Richard Middleton Smith, a former POW working on the Thai-Burma Railway, we get an insight into the state of the Asian labourers at the end of the war: “In September 1945 in Thailand, as the repatriation of Allied prisoners of war got underway, a small group of Malayan and Straits Settlements Volunteer Force members took the selfless decision to stay behind to locate and repatriate to Malaya the surviving 27,000 Asian labourers…

“These Volunteers, all of whom spoke Malay and Tamil, considered this task a debt of honour. Among them was Richard Middleton Smith… Formed in two groups, they left Bangkok Railway station on August 28th 1945 to locate the labour camps from Kanchanaburi to 185 Kilo Camp where Richard had ended his time as a POW.

“He recalled ‘At every camp the labourers seemed overjoyed to see us and meet those of us who could speak to them in their own language. In a number of camps they seemed unaware the war was over. Their first wish was to get back to Malaya and see their relatives’.”6

Bapak was among the rōmusha who were free but did not know how to get back home on their own. According to his son Ally, Bapak met a certain “Major Pink” whom he had known in Singapore before the war. “Major Pink” and some of the British POWs helped Bapak find his way to Bangkok in the back of a truck and from Bangkok, he was repatriated to Singapore. I have not been able to unearth precise information about “Major Pink”. I subsequently found out that that there was a Johor planter manager named Pierrepont C.H.F. (Cyril Horace Frederick) ‘Pink’ who was a POW in Thailand. He could have been the “Major Pink” my grandfather encountered and received help from.

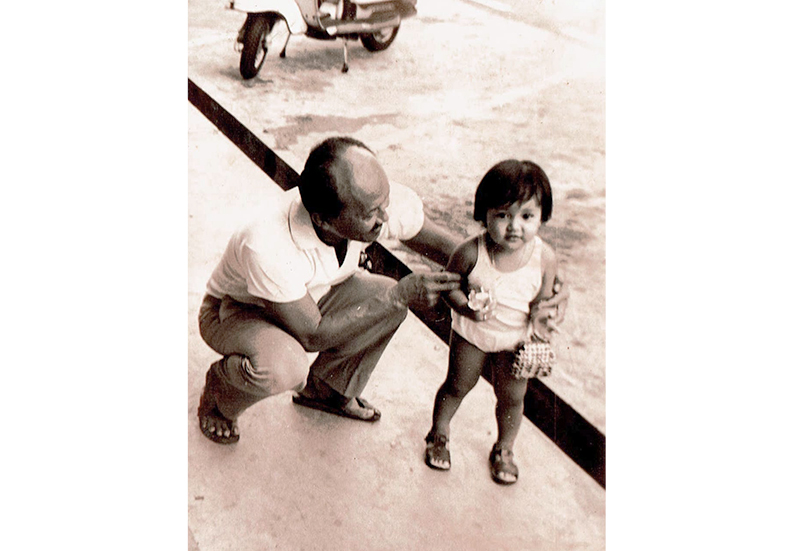

Bapak returned to Singapore in late 1945 or early 1946. My grandmother recalled how he just appeared at the front door of the family home one day. Despite not receiving any news at all from him from the time he left Singapore in 1942, my grandmother had waited patiently for his return. Perhaps, deep inside her she knew that he was alive and would make his way home to see his first-born child, Asiah Kosman, my mother, whom he had never met.

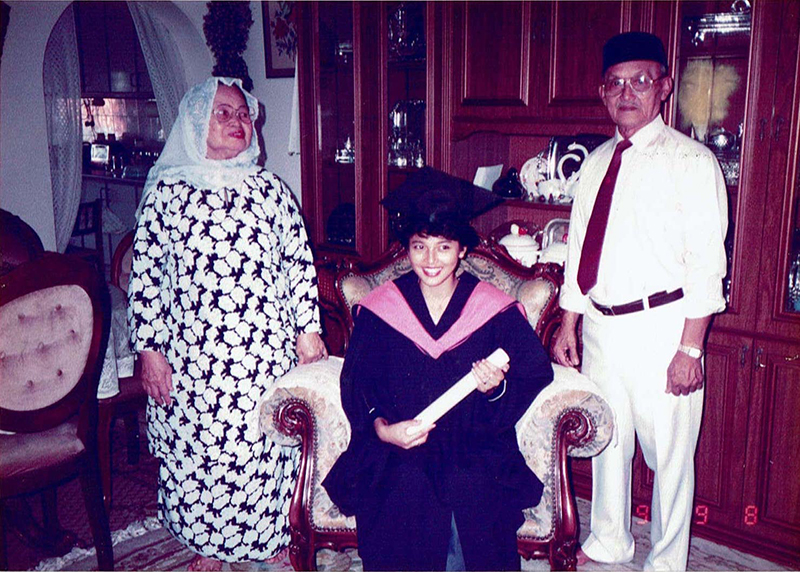

Remarkably, Bapak continued to volunteer with the British military upon his return. On 6 May 1949, Lance Bombardier K.B. Hassan (Kosman bin Hassan), service no. 49067 of the Singapore Royal Artillery, was awarded the Efficiency Medal for his long service. For his part in the war, he was also presented with other medals: the War Medal 1939–1945, the Pacific Star, 1939–1945 Star and the Defence Medal.

Following his return to Singapore, Bapak became a driver for the Dutch Lady company delivering milk to households all over Singapore. In the relative calm of the post-war years in Singapore, my grandparents went on to have four more children – three boys, Ally, Latif and Fadilah and another daughter, Rubiah. Bapak continued to work as a driver until after Singapore’s independence. In 1969, he started a drinks stall in the canteen of newly opened Chai Chee Secondary School next to the family home on Sennett Road.

Like many of his generation who had experienced the war in a very personal way, Bapak never really liked to talk about his time on the Death Railway. He would mention the railway in passing, maybe when certain things triggered a memory. Whenever he encountered people from Thailand, he would be happy to break into Thai. But Bapak never consciously sat us down to tell us about the Death Railway. He never lectured us on the lessons that it taught him, answering questions only when asked. And he apparently never harboured any ill-feelings towards the Japanese; I have never heard him say a harsh word against them.

In spite of what he went through and maybe because of it, Bapak was a very steady, patient man. He never got angry, never shouted. There was always such a quiet strength about him and he was always ready to help anyone who needed him, be it family, friend, colleague or stranger.

He had such a strong belief in community, in the kindness of people and in humanity. From the early years of Singapore’s independence until his death in 1992, Bapak was an active grassroots member at the Siglap Community Centre. For his community service, he received the Grand Award for Community Service medal. Bapak had witnessed the best and worst of humankind on the Death Railway. But rather than choosing to hate, he chose to forgive. We were lucky to have gotten him back alive; many other families in Malaya, Java, Sumatra and Burma where the rōmusha had been recruited from were not so lucky.

In June 1992, Bapak and Mak were in Kuala Lumpur to visit Uncle Ally and his family when he fell seriously ill. Despite the gravity of his illness, Bapak insisted on being driven back home. His last wish was to spend his final days in Singapore. On 1 July, not long after returning to Singapore, Bapak passed away at the Singapore General Hospital with me and my cousin Alfie by his side.

It is now exactly 30 years since Bapak’s passing, and reflecting on his life has brought on both tears and smiles as I remember a grandfather who lived life to the fullest, in the best and worst of times.

Shirlene Noordin is the founder of Phish Communications, a communications consultancy specialising in arts and culture.

Shirlene Noordin is the founder of Phish Communications, a communications consultancy specialising in arts and culture.NOTES

-

“Burma-Thailand Railway,” National Museum Australia, updated 12 July 2022, https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/burma-thailand-railway. ↩

-

Takuma Melber, “The Labour Recruitment of Local Inhabitants as Rōmusha in Japanese-Occupied South East Asia,” International Review of Social History 61, no. 4 (2016): 169. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Robert Hardie, The Burma-Siam Railway: The Secret Diary of Dr. Robert Hardie, 1942–1945 (London: Imperial War Museum, 1984, c1983), 102. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 940.5425 HAR-[JSB]) ↩

-

Eric Lomax, The Railway Man (London: Jonathan Cape, 1995), 83. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 940.5481411 LOM-[WAR]) ↩

-

Communication with Jonathan Moffat. ↩

-

Jonathan Moffat, “Obituary for Richard Middleton Smith MC 1914-2011,” The Times, 29 February 2012, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/richard-middleton-smith-st8nwb0kdkh. ↩